Lurasidone (Monograph)

Brand name: Latuda

Drug class: Atypical Antipsychotics

Warning

- Increased Mortality in Geriatric Patients with Dementia-related Psychosis

-

Geriatric patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic agents are at an increased risk of death.1 28

-

Antipsychotic agents, including lurasidone, are not approved for the treatment of dementia-related psychosis.1

- Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Pediatric and Young Adult Patients

-

Antidepressants increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (suicidality) compared with placebo in children, adolescents, and young adults (18–24 years of age).1

-

Closely monitor all patients who are started on lurasidone therapy for clinical worsening and emergence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors; involve family members and/or caregivers in this process.1

Introduction

Benzisothiazol-derivative; atypical or second-generation antipsychotic agent.1 2

Uses for Lurasidone

Schizophrenia

Treatment of schizophrenia in adults and adolescents 13–17 years of age.1 2 5 98 100 101 102 103 104 105

American Psychiatric Association (APA) and Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense recommend antipsychotic medications for acute and long-term maintenance treatment of schizophrenia.107 108 Choice of antipsychotic should be based on patient preference, past response to therapy, concurrent medical conditions, and medication-specific factors (e.g., adverse effect profile, available formulations, potential drug interactions, receptor binding profiles, pharmacokinetic considerations).107

Depression Associated with Bipolar Disorder

Treatment (alone or in combination with lithium or valproate) of major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder (bipolar depression) in adults.1

Monotherapy for treatment of major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder (bipolar depression) in pediatric patients 10–17 years of age.1 99

Legacy guideline from APA does not address role for antipsychotic medications in the treatment of bipolar depressive episodes without psychotic features.109 Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense guidelines recommend quetiapine monotherapy for the treatment of acute bipolar depression; if quetiapine is not selected (based on patient preference and characteristics), cariprazine, lumateperone, lurasidone, or olanzapine monotherapy is recommended.110 Olanzapine, lurasidone, or quetiapine may be used in combination with lithium or valproate for the prevention of recurrent bipolar depressive episodes.110

Other Uses

Has been used for treatment ofmajor depressive disorder with mixed features (subthreshold hypomanic symptoms)† [off-label].106

Lurasidone Dosage and Administration

General

Pretreatment Screening

-

Perform fasting blood glucose testing at baseline in patients with risk factors for diabetes (e.g., obesity, family history of diabetes).1

-

Complete fall risk assessments when initiating lurasidone in patients with concomitant diseases, conditions, or medications that could exacerbate the risk of falls.1

Patient Monitoring

-

Patients receiving lurasidone should be monitored for possible worsening of depression, suicidality, or unusual changes in behavior, especially at the beginning of therapy or during periods of dosage adjustments.1

-

Patients with a preexisting low WBC or a history of drug-induced leukopenia or neutropenia should have their CBC monitored frequently during the first few months of therapy.1 In the absence of other causes, lurasidone should be discontinued at the first sign of a decline in WBC.1

-

Monitor patients for hyperglycemia/diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and weight gain.1 Patients with an established diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) should be regularly assessed for worsening of glucose control and periodically monitor fasting blood glucose in patients with risk factors for diabetes (e.g., obesity, family history of diabetes).1

-

Monitor heart rate and blood pressure in patients with an increased risk of orthostatic hypotension and syncope (i.e., those with dehydration, receiving antihypertensives, history of cardiovascular disease or cerebrovascular disease), including those who are naïve to antipsychotic therapy.1

-

Because therapy with lurasidone can increase the risk of developing a manic or hypomanic episode, patients should be monitored for the development of mania or hypomania.1

-

Monitor patients for signs and symptoms of neuroleptic malignant syndrome and tardive dyskinesia during therapy.1

-

In patients receiving long-term lurasidone therapy, assess fall risk on an ongoing basis.1

Dispensing and Administration Precautions

-

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) includes Latuda and Lantus on their ISMP List of Confused Drug Names, and recommends using special safeguards to ensure the accuracy of prescriptions for these drugs.111

Administration

Oral Administration

Administer tablets orally once daily, usually in the morning or evening.1 Take with food (containing at least 350 calories) to increase absorption.1

Dosage

Available as lurasidone hydrochloride; dosage expressed in terms of the salt.1

Pediatric Patients

Schizophrenia

Oral

For acute treatment in adolescents 13–17 years of age, recommended initial dosage is 40 mg once daily.1 Initial dosage titration not required.1 Dosages ranging from 40–80 mg daily were effective in a controlled trial.1

Maximum recommended dosage for treatment of schizophrenia is 80 mg daily.1

Long-term (i.e., >6 weeks) efficacy not established in controlled trials.1 Periodically reassess need for continued therapy.1

Depression Associated with Bipolar Disorder

Oral

As monotherapy in pediatric patients 10–17 years of age, initially, 20 mg once daily.1 Initial dosage titration not required.1 Dosage may be increased after 1 week based on clinical response.1 Dosages ranging from 20–80 mg daily as monotherapy were effective in a controlled trial.1 By the end of the trial, majority (67%) of patients were receiving 20 or 40 mg daily.1

Maximum recommended dosage for treatment of bipolar depression as monotherapy is 80 mg daily.1

Long-term (i.e., >6 weeks) efficacy not established in controlled trials.1 Periodically reassess need for continued therapy.1

Adults

Schizophrenia

Oral

For acute treatment, recommended initial dosage is 40 mg once daily.1 Initial dosage titration not required.1 Dosages ranging from 40–160 mg daily were effective in controlled trials.1

Maximum recommended dosage for treatment of schizophrenia is 160 mg daily.1

Long-term (i.e., >6 weeks) efficacy not established in controlled trials.1 Periodically reassess need for continued therapy.1

Depression Associated with Bipolar Disorder

Oral

As monotherapy or adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate, initially, 20 mg once daily.1 Initial dosage titration not required.1 Although dosages ranging from 20–120 mg daily were effective in controlled trials, in the monotherapy study the higher dosage range (80–120 mg daily) did not provide additional efficacy over the lower dosage range (20–60 mg daily).1

Maximum recommended dosage for treatment of bipolar depression, either as monotherapy or as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate, is 120 mg daily.1

Long-term (i.e., >6 weeks) efficacy not established in controlled trials.1 Periodically reassess need for continued therapy.1

Dosage Modifications Due to Concomitant Use of Drugs Affecting Hepatic Microsomal Enzymes

Initiating a concomitant moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor (e.g., atazanavir, diltiazem, erythromycin, fluconazole, verapamil) in patients already receiving lurasidone: Reduce lurasidone dosage by 50% of original dosage.1 In patients already receiving a moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor who are initiating lurasidone, recommended initial lurasidone dosage is 20 mg daily.1 Maximum recommended dosage is 80 mg daily.1

Concomitant use with a moderate CYP3A4 inducer (e.g., bosentan, efavirenz, etravirine, modafinil, nafcillin) may require lurasidone dosage increase after chronic therapy (i.e., ≥7 days) with CYP3A4 inducer.1

Do not administer lurasidone concomitantly with potent CYP3A4 inhibitors (e.g., clarithromycin, ketoconazole, ritonavir, voriconazole) or potent CYP3A4 inducers (e.g., carbamazepine, phenytoin, rifampin, St. John's wort [Hypericum perforatum]).1

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

Severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score 10–15): Initially, 20 mg daily.1 Do not exceed 40 mg daily.1

Moderate hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score 7–9): Initially, 20 mg daily.1 Do not exceed 80 mg daily.1

Mild hepatic impairment: Dosage adjustment does not appear necessary.1

Renal Impairment

Moderate or severe renal impairment (Clcr <50 mL/minute): Initially, 20 mg daily.1 Do not exceed 80 mg daily.1

Mild renal impairment (Clcr ≥50 mL/minute): Dosage adjustment does not appear necessary.1

Geriatric Patients

Not known whether dosage adjustment is necessary based on age alone.1

Cautions for Lurasidone

Contraindications

-

Known hypersensitivity to lurasidone hydrochloride or any components in the formulation.1 Angioedema reported.1

-

Concurrent use of potent CYP3A4 inhibitors (e.g., clarithromycin, ketoconazole, ritonavir, voriconazole) or potent CYP3A4 inducers (e.g., carbamazepine, phenytoin, rifampin, St. John's wort [Hypericum perforatum]).1

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Increased Mortality in Geriatric Patients with Dementia-related Psychosis

Increased risk of death with antipsychotics in geriatric patients with dementia-related psychosis.1 28 (See Boxed Warning.)

Antipsychotic agents, including lurasidone, are not approved for the treatment of dementia-related psychosis.1

Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors in Pediatric and Young Adult Patients

Based on pooled analysis, increased incidence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in pediatric and young adult patients receiving antidepressant therapy.1 (See Boxed Warning). No suicides occurred in pediatric trials.1

Not known if risk extends to longer-term use (i.e., >4 months) of antidepressant therapy.1

Increased risk not demonstrated in adults >24 years of age and reduced risk observed in adults ≥65 years of age.1

Appropriately monitor for clinical worsening and the emergence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, particularly during initiation of therapy (i.e., the first few months) and during periods of dosage adjustments.1 Family members and caregivers must also monitor for behavioral changes and notify the prescriber if these occur.1

Consider changing or discontinuing therapy in patients whose depression is persistently worse or in those who are experiencing emergent suicidal thoughts or behaviors.1

Other Warnings and Precautions

Cerebrovascular Events in Geriatric Patients with Dementia-related Psychosis

Increased incidence of adverse cerebrovascular events (cerebrovascular accidents and TIAs), including fatalities, observed in geriatric patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with certain atypical antipsychotic agents (aripiprazole, olanzapine, risperidone) in placebo-controlled studies.1 28 Lurasidone is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis.1

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), a potentially fatal syndrome characterized by hyperpyrexia, muscle rigidity, altered mental status, and autonomic instability, reported with antipsychotic agents, including lurasidone.1

Immediately discontinue therapy and initiate supportive and symptomatic treatment if NMS occurs.1

Tardive Dyskinesia

Tardive dyskinesia, a syndrome of potentially irreversible, involuntary dyskinetic movements, reported with use of antipsychotic agents, including lurasidone.1

Reserve long-term antipsychotic treatment for patients with chronic illness known to respond to antipsychotic agents, and for whom alternative, equally effective, but potentially less harmful treatments are not available or appropriate.1 In patients requiring chronic treatment, use smallest dosage and shortest duration of treatment producing a satisfactory clinical response; periodically reassess need for continued therapy.1

Consider discontinuance of lurasidone if signs and symptoms of tardive dyskinesia appear.1 However, some patients may require treatment despite presence of the syndrome.1

Metabolic Changes

Atypical antipsychotic agents are associated with metabolic changes that may increase cardiovascular and cerebrovascular risk (e.g., hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, weight gain).1 While all atypical antipsychotics produce some metabolic changes, each drug has its own specific risk profile.1

Hyperglycemia and Diabetes Mellitus

Hyperglycemia, sometimes severe and associated with ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar coma, or death, reported in patients receiving atypical antipsychotic agents.1 In short-term clinical trials in adults, clinically important differences between lurasidone and placebo in mean change from baseline to end point in serum glucose concentrations not observed.1

Periodically monitor patients with an established diagnosis of diabetes mellitus for worsening of glucose control and perform fasting blood glucose testing at baseline and periodically in patients with risk factors for diabetes (e.g., obesity, family history of diabetes).1

Some patients who developed hyperglycemia while receiving an atypical antipsychotic have required continuance of antidiabetic treatment despite discontinuance of the suspect drug; in other patients, hyperglycemia resolved with discontinuance of the antipsychotic.1

Dyslipidemia

Undesirable changes in lipid parameters observed in patients treated with some atypical antipsychotics.1 However, clinically important effects of lurasidone on serum lipids not observed in short- and longer-term clinical studies.1

Weight Gain

Weight gain observed with atypical antipsychotic therapy.1 Manufacturer recommends monitoring of weight during lurasidone therapy.1

Hyperprolactinemia

May cause elevated serum prolactin concentrations, which may persist during chronic administration and cause clinical disturbances (e.g., galactorrhea, amenorrhea, gynecomastia, impotence); chronic hyperprolactinemia associated with hypogonadism may lead to decreased bone density in both females and males.1

If contemplating lurasidone therapy in a patient with previously detected breast cancer, consider that approximately one-third of human breast cancers are prolactin-dependent in vitro.1 However, epidemiological studies have reported inconsistent findings of such relationships.1

Leukopenia, Neutropenia, and Agranulocytosis

Leukopenia and neutropenia temporally related to antipsychotic agents, including lurasidone, reported.1 Agranulocytosis (including fatal cases) also reported with other antipsychotic agents.1

Possible risk factors for leukopenia and neutropenia include preexisting low WBC count and a history of drug-induced leukopenia or neutropenia.1 Monitor CBC frequently during the first few months of therapy in patients with such risk factors.1 Discontinue lurasidone at the first sign of a decline in WBC count in the absence of other causative factors.1

Carefully monitor patients with neutropenia for signs and symptoms of infection (e.g., fever) and treat promptly if they occur.1 Discontinue lurasidone if severe neutropenia (ANC <1000/mm3) occurs; monitor WBC until recovery occurs.1

Orthostatic Hypotension and Syncope

Risk of orthostatic hypotension associated with dizziness, lightheadedness, tachycardia or bradycardia, and syncope, particularly early in treatment and when dosage is increased, because of lurasidone's α1-adrenergic blocking activity.1

Orthostatic hypotension (0.3%) and syncope (0.1%) reported in lurasidone-treated patients in short-term schizophrenia trials; not reported in short-term bipolar depression trials.1

Patients at increased risk of these adverse reactions or of developing complications from hypotension include those with dehydration, hypovolemia, a history of cardiovascular disease (e.g., heart failure, MI, ischemic heart disease, conduction abnormalities), or a history of cerebrovascular disease, and patients receiving concomitant antihypertensive therapy and those who are antipsychotic-naive.1 Consider a lower initial dosage and more gradual dosage titration and monitor orthostatic vital signs in such patients.1

Falls

Possible somnolence, postural hypotension, and motor and sensory instability, which can lead to falls reported.1 Complete fall risk assessments when initiating lurasidone in those with diseases, conditions, or medications that could exacerbate the risk of falls.1 In patients receiving long-term antipsychotic therapy, assess fall risk on an ongoing basis.1

Seizures

Seizures reported in 0.1% of both lurasidone-treated patients and placebo recipients in short-term adult schizophrenia trials.1 No reports of seizures or convulsions in lurasidone-treated patients in short-term bipolar depression trials.1

Use with caution in patients with a history of seizures or with conditions that lower the seizure threshold (e.g., dementia of the Alzheimer’s type); conditions that lower seizure threshold may be more prevalent in patients ≥65 years of age.1

Cognitive and Motor Impairment

Judgment, thinking, or motor skills may be impaired.1 Somnolence (including hypersomnia, hypersomnolence, and sedation) reported in 17 and 7.3–13.8% of lurasidone-treated patients in schizophrenia and bipolar depression (as monotherapy) adult clinical trials, respectively; frequency of somnolence may be dose related.1

Body Temperature Regulation

Antipsychotic agents may disrupt ability to regulate core body temperature.1

Use appropriate caution in patients who will be experiencing conditions that may contribute to an elevation in core body temperature (e.g., strenuous exercise, extreme heat, concomitant use of agents with anticholinergic activity, dehydration).1

Activation of Mania/Hypomania

Antidepressants can increase risk of developing manic or hypomanic episodes, particularly in patients with bipolar disorder.1 Monitor patients for emergence of such episodes during therapy.1

Dysphagia

Esophageal dysmotility and aspiration associated with the use of antipsychotic agents.1

Aspiration pneumonia is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in geriatric patients, particularly in those with advanced Alzheimer's dementia.1 Lurasidone is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis and should be used with caution in patients at risk for aspiration pneumonia.1

Neurologic Adverse Reactions in Patients with Parkinsonian Syndrome or Dementia with Lewy Bodies

Patients with parkinsonian syndrome or dementia with Lewy bodies reportedly have an increased sensitivity to antipsychotic agents.1 Clinical manifestations of increased sensitivity reportedly include confusion, obtundation, postural instability with frequent falls, extrapyramidal symptoms, and features consistent with NMS.1

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Pregnancy registry available that monitors pregnancy outcomes.1 Contact the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics at 1-866-961-2388 or visit [Web].1

Risk for extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms (e.g., agitation, hypertonia, hypotonia, tardive dyskinetic-like symptoms, tremor, somnolence, respiratory distress, feeding disorder) in neonates exposed to antipsychotic agents during the third trimester; monitor neonates exhibiting such symptoms and manage appropriately.1 Symptoms were self-limiting in some neonates but varied in severity; some infants required prolonged hospitalization.1

Lactation

Lurasidone studies not conducted to assess presence in breastmilk.1 Effects of lurasidone on breast-fed infant or milk production not known.1 Distributes into milk in rats.1 Weigh the developmental and health benefits of breast-feeding along with the mother's clinical need for the drug and any potential adverse effects on the breast-fed infant from lurasidone or the underlying maternal condition.1

Pediatric Use

Safety and effectiveness established for the treatment of schizophrenia in adolescents 13–17 years of age.1 Safety and effectiveness for treatment of schizophrenia not established in pediatric patients <13 years of age.1

Safety and effectiveness established for the treatment of bipolar depression established in pediatric patients 10–17 years of age.1 Safety and effectiveness for treatment of bipolar depression not established in pediatric patients <10 years of age.1

Long-term (104-week), open-label study of pediatric patients 6–17 years of age indicate minimal effects on growth curve based on z-scores.1

Geriatric Use

Insufficient experience in patients ≥65 years of age to determine whether they respond differently than younger adults.1

Geriatric patients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic agents are at an increased risk of death;1 increased incidence of cerebrovascular events also observed with certain atypical antipsychotic agents.1 Lurasidone is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis.1

In pooled data analyses, a reduced risk of suicidality was observed in adults ≥65 years of age with antidepressant therapy compared with placebo.1

Hepatic Impairment

Greater lurasidone exposure in patients with moderate to severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score ≥7) compared to normal hepatic function, which may increase risk of adverse reactions.1

Renal Impairment

Greater lurasidone exposure in moderate or severe renal impairment (Clcr<50 mL/minute) compared to normal renal function, which may increase risk of adverse reactions.1

Common Adverse Effects

Adults with schizophrenia (≥5%): Somnolence (hypersomnia, hypersomnolence, sedation),2 akathisia, extrapyramidal symptoms (parkinsonian symptoms, dyskinesia), nausea.1

Adolescents 13–17 years of age with schizophrenia (≥5%): Somnolence (including hypersomnia, hypersomnolence, and sedation), nausea, akathisia, extrapyramidal symptoms (non-akathisia), rhinitis (80 mg dosage only), vomiting.1

Adults with bipolar depression (as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate) (≥5%): Somnolence (hypersomnia, hypersomnolence, sedation), akathisia, extrapyramidal symptoms (parkinsonian symptoms, dyskinesia).1

Pediatric patients 10–17 years of age with bipolar depression (as monotherapy) (≥5%): Nausea, weight increase, insomnia.1

Drug Interactions

Metabolized principally by CYP3A4.1 Not a substrate of CYP isoenzymes 1A1, 1A2, 2A6, 4A11, 2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 2E1, or organic anion transporter polypeptide (OATP) 1B1 or OATP1B3.1 Likely a substrate of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP).1 Not expected to inhibit OATP1B1, OATP1B3, organic cation transporter (OCT) 1, OCT2, organic anion transporter (OAT)1, OAT3, multidrug and toxin extrusion transporter (MATE)1, MATE2K, or bile salt exporter pump (BSEP).1 Not a clinically important inhibitor of P-gp, but may inhibit BCRP.1

Drugs Affecting or Metabolized by Hepatic Microsomal Enzymes

Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors: Potential pharmacokinetic interaction.1 Concomitant use contraindicated.1

Moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors: Potential pharmacokinetic interaction.1 Reduce lurasidone dosage to 50% of original dosage when a moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor is added to therapy.1 In patients receiving a moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor in whom lurasidone is initiated, recommended initial lurasidone hydrochloride dosage is 20 mg daily and maximum recommended dosage is 80 mg daily.1

Strong CYP3A4 inducers: Potential pharmacokinetic interaction.1 Concomitant use contraindicated.1

Moderate CYP3A4 inducers: Potential pharmacokinetic interaction.1 May need to increase lurasidone dosage after chronic therapy (i.e., ≥7 days) with the CYP3A4 inducer.1

Specific Drugs and Foods

|

Drug or Food |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Anticholinergic agents |

Possible disruption of body temperature regulation1 |

|

|

Atazanavir |

Atazanavir (moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor) may increase lurasidone exposure1 |

When atazanavir is added to lurasidone therapy, reduce lurasidone dosage to 50% of original dosage1 In patients receiving atazanavir, recommended initial lurasidone hydrochloride dosage is 20 mg daily and maximum recommended dosage is 80 mg daily1 |

|

Bosentan |

Bosentan (moderate CYP3A4 inducer) potentially can decrease exposure of lurasidone1 |

When bosentan is used concomitantly, an increase in lurasidone dosage may be necessary after chronic therapy (i.e., ≥7 days) with the CYP3A4 inducer1 |

|

Carbamazepine |

Carbamazepine (a strong CYP3A4 inducer) potentially can decrease exposure of lurasidone 1 |

Concomitant use contraindicated1 |

|

Clarithromycin |

Clarithromycin (a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor) may substantially increase lurasidone exposure 1 |

Concomitant use contraindicated1 |

|

Diltiazem |

Concomitant use of diltiazem (a moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor) can increase lurasidone exposure1 |

When diltiazem is added to lurasidone therapy, reduce lurasidone dosage to 50% of original dosage1 In patients receiving diltiazem, recommended initial lurasidone hydrochloride dosage is 20 mg daily and maximum recommended dosage is 80 mg daily1 |

|

Efavirenz |

Efavirenz (moderate CYP3A4 inducer) potentially can decrease lurasidone exposure1 |

When efavirenz is used concomitantly, an increase in lurasidone dosage may be necessary after chronic therapy (i.e., ≥7 days) with the CYP3A4 inducer1 |

|

Erythromycin |

Erythromycin (a moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor) may increase lurasidone exposure1 |

When erythromycin is added to lurasidone therapy, reduce lurasidone dosage to 50% of original dosage1 In patients receiving erythromycin, recommended initial lurasidone hydrochloride dosage is 20 mg daily and maximum recommended dosage is 80 mg daily1 |

|

Etravirine |

Etravirine (moderate CYP3A4 inducer) potentially can decrease lurasidone exposure1 |

When etravirine is used concomitantly, an increase in lurasidone dosage may be necessary after chronic therapy (i.e., ≥7 days) with the CYP3A4 inducer1 |

|

Fluconazole |

Fluconazole (a moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor) may increase lurasidone exposure1 |

When fluconazole is added to lurasidone therapy, reduce lurasidone dosage to 50% of original dosage1 In patients receiving fluconazole, recommended initial lurasidone hydrochloride dosage is 20 mg daily and maximum recommended dosage is 80 mg daily1 |

|

Grapefruit |

Possible increased exposure of lurasidone1 |

Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

Hypotensive agents |

Possible additive hypotensive effects; may result in orthostatic hypotension and syncope1 |

Consider use of lower initial lurasidone dosage and more gradual titration; monitor orthostatic vital signs1 |

|

Ketoconazole |

Ketoconazole (a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor) may substantially increase lurasidone exposure1 |

Concomitant use contraindicated1 |

|

Lithium |

Minimal change in lurasidone or lithium serum concentration1 |

Dosage adjustment of lurasidone and lithium not required1 |

|

Modafinil |

Modafinil (moderate CYP3A4 inducer) potentially can decrease lurasidone exposure1 |

When modafinil is used concomitantly, an increase in lurasidone dosage may be necessary after chronic therapy (i.e., ≥7 days) with the CYP3A4 inducer1 |

|

Nafcillin |

Nafcillin (moderate CYP3A4 inducer) potentially can decrease lurasidone exposure1 |

When nafcillin is used concomitantly, an increase in lurasidone dosage may be necessary after chronic therapy (i.e., ≥7 days) with the CYP3A4 inducer1 |

|

Phenytoin |

Phenytoin (potent CYP3A4 inducer) potentially can decrease lurasidone exposure1 |

Concomitant use contraindicated1 |

|

Rifampin |

Rifampin (potent CYP3A4 inducer) can potentially decrease lurasidone exposure1 |

Concomitant use contraindicated1 |

|

Ritonavir |

Ritonavir (potent CYP3A4 inhibitor) may substantially increase lurasidone exposure 1 |

Concomitant use contraindicated1 |

|

St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum) |

St. John's wort (potent CYP3A4 inducer) potentially can decrease lurasidone exposure1 |

Concomitant use contraindicated1 |

|

Valproate |

Minimal change in lurasidone or valproate serum concentrations1 |

Dosage adjustment of lurasidone and valproate not required1 |

|

Verapamil |

Verapamil (moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor) may increase lurasidone exposure1 |

When verapamil is added to lurasidone therapy, reduce lurasidone dosage to 50% of original dosage1 In patients receiving verapamil, recommended initial lurasidone hydrochloride dosage is 20 mg daily and maximum recommended dosage is 80 mg daily1 |

|

Voriconazole |

Voriconazole (potent CYP3A4 inhibitor) may substantially increase lurasidone exposure 1 |

Concomitant use contraindicated1 |

Lurasidone Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Pharmacokinetics dose-proportional over total daily dosage range of 20–160 mg.1

Rapidly absorbed following oral administration; peak serum concentrations achieved within about 1–3 hours.1

Approximately 9–19% of an orally administered dose is absorbed.1

Steady-state concentrations of lurasidone achieved within 7 days.1

Food

Mean peak serum concentrations and AUCs of lurasidone increased by about threefold and twofold, respectively, when administered with food compared with values obtained under fasting conditions.1 Exposure not affected as meal size increased from 350 to 1000 calories and was independent of fat content.1

Special Populations

Exposure generally similar in children and adolescents (10–17 years of age) compared to adults for oral dosages of 40–160 mg, without adjusting for body weight.1

In geriatric patients with psychosis, serum lurasidone concentrations were similar to those observed in younger adults.1

Distribution

Extent

Distributes into milk in rats; not known whether the drug and/or its metabolites distribute into human milk.1

Plasma Protein Binding

Highly bound (approximately 99%) to plasma proteins.1

Elimination

Metabolism

Metabolized mainly via CYP3A4.1 Major biotransformation pathways are oxidative N-dealkylation, hydroxylation of norbornane ring, and S-oxidation.1

Metabolized into 2 active metabolites (ID-14283 and ID-14326) and 2 major inactive metabolites (ID-20219 and ID-20220); pharmacologic activity primarily due to parent drug.1

Elimination Route

Following administration of a single radiolabeled dose approximately 80% recovered in feces and 9% in urine.1

Half-life

Averages 18 hours.1

Stability

Storage

Oral

Tablets

25°C (may be exposed to 15–30°C).1

Actions

-

Exact mechanism of action in schizophrenia and bipolar depression unknown; efficacy may be mediated through a combination of antagonist activity at central dopamine type 2 (D2) and serotonin type 2 (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT2A]) receptors.1

-

Exhibits high affinity for D2, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT7 receptors and moderate affinity for α2C-adrenergic receptors in vitro.1 Acts as a partial agonist at 5-HT1A receptors and is an antagonist at α2A-adrenergic receptors in vitro.1

-

Exhibits affinity for α1-adrenergic receptors and little or no affinity for histamine (H1) receptors and muscarinic (M1) receptors.1

Advice to Patients

-

Advise patients to read the FDA-approved patient labeling (Medication Guide).1

-

Advise patients and caregivers to remain alert to and immediately report emergence of suicidality, especially early during treatment or during periods of dosage adjustment.1

-

Inform patients and caregivers about the risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), a rare but potentially life-threatening syndrome.1 Instruct patients and caregivers to contact their healthcare provider or report to an emergency room if they have signs or symptoms of NMS.1

-

Inform patients on the signs and symptoms of tardive dyskinesia and to contact their provider if these abnormal movements develop.1

-

Inform patients and caregivers about the risk of metabolic changes (e.g., hyperglycemia and diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, weight gain, cardiovascular reactions) with lurasidone, how to recognize symptoms, and the need for specific monitoring, including blood glucose, lipids, and weight during therapy.1

-

Inform patients of the signs and symptoms of hyperprolactinemia that may occur with chronic lurasidone therapy.1 Advise patients to seek medical attention if they experience any of the following: amenorrhea or galactorrhea in females, erectile dysfunction or gynecomastia in males.1

-

Inform patients about the risk of orthostatic hypotension, especially when initiating or restarting treatment or during dosage increases.1

-

Risk of leukopenia/neutropenia.1 Advise patients with preexisting low leukocyte counts or a history of drug-induced leukopenia/neutropenia that they should have their complete blood cell (CBC) count monitored during lurasidone therapy.1

-

Because somnolence (i.e., sleepiness, drowsiness) may be associated with lurasidone, patients should be cautioned about performing activities requiring mental alertness, such as driving or operating hazardous machinery, while taking lurasidone until they gain experience with the drug’s effects.1

-

Advise patients and caregivers to observe patients for signs or symptoms of mania or hypomania.1

-

Advise patients to avoid eating grapefruit or drinking grapefruit juice during lurasidone therapy, since lurasidone blood concentrations may be affected.1

-

Advise patients of the importance of avoiding overheating and dehydration.1

-

Advise patients to inform their clinicians of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs or herbal supplements, as well as any concomitant illnesses (e.g., cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, seizures).1

-

Advise women to inform their clinicians if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1 Inform patients that lurasidone exposure can cause extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms in a neonate.1 Inform patients that there is a pregnancy registry that monitors pregnancy outcomes in women exposed to lurasidone.1

-

Inform patients of other important precautionary information.1

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer’s labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

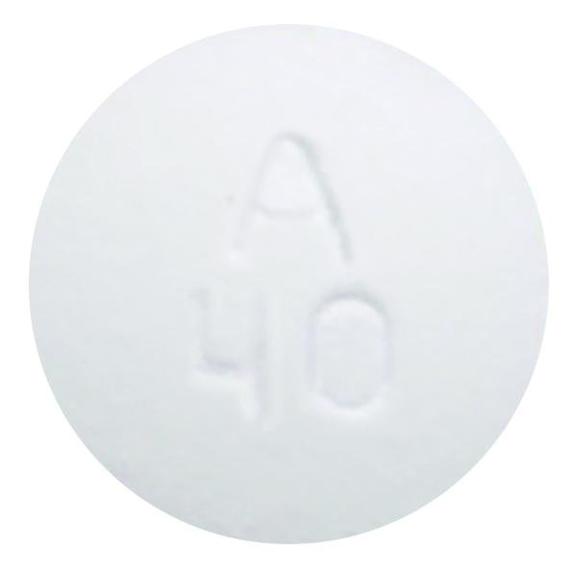

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Tablets, film coated |

20 mg |

Latuda |

Sunovion |

|

40 mg |

Latuda |

Sunovion |

||

|

60 mg |

Latuda |

Sunovion |

||

|

80 mg |

Latuda |

Sunovion |

||

|

120 mg |

Latuda |

Sunovion |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions March 10, 2025. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

1. Sumitomo Pharma America Inc. Latuda (lurasidone hydrochloride) tablets prescribing information. Marlborough, MA; 2025 Jan.

2. Nakamura M, Ogasa M, Guarino J et al. Lurasidone in the treatment of acute schizophrenia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009; 70:829-36. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19497249

5. Meltzer HY, Cucchiaro J, Silva R et al. Lurasidone in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and olanzapine-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011; 168:957-67. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21676992

9. Meyer JM, Loebel AD, Schweizer E. Lurasidone: a new drug in development for schizophrenia. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009; 18:1715-26. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19780705

28. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004; 161(2 Suppl):1-56.

85. Chiu YY, Ereshefsky L, Preskorn SH et al. Lurasidone drug-drug interaction studies: a comprehensive review. Drug Metabol Drug Interact. 2014; :. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24825095

86. Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R et al. Lurasidone monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014; 171:160-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24170180

87. Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R et al. Lurasidone as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate for the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014; 171:169-77. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24170221

88. Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Sarma K et al. Efficacy and safety of lurasidone 80 mg/day and 160 mg/day in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2013; 145:101-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23415311

98. Goldman R, Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Deng L, Findling RL. Efficacy and Safety of Lurasidone in Adolescents with Schizophrenia: A 6-Week, Randomized Placebo-Controlled Study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017 Aug;27(6):516-525. doi: 10.1089/cap.2016.0189. Epub 2017 May 5. PMID: 28475373; PMCID: PMC5568017.

99. DelBello MP, Goldman R, Phillips D, Deng L, Cucchiaro J, Loebel A. Efficacy and Safety of Lurasidone in Children and Adolescents With Bipolar I Depression: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017 Dec;56(12):1015-1025. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.10.006. Epub 2017 Oct 13. PMID: 29173735.

100. Ogasa M, Kimura T, Nakamura M, Guarino J. Lurasidone in the treatment of schizophrenia: a 6-week, placebo-controlled study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013 Feb;225(3):519-30. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2838-2. Epub 2012 Aug 19. PMID: 22903391; PMCID: PMC3546299.

101. Nasrallah HA, Silva R, Phillips D, Cucchiaro J, Hsu J, Xu J, Loebel A. Lurasidone for the treatment of acutely psychotic patients with schizophrenia: a 6-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2013 May;47(5):670-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.01.020. Epub 2013 Feb 17. PMID: 23421963.

102. Stahl SM, Cucchiaro J, Simonelli D, Hsu J, Pikalov A, Loebel A. Effectiveness of lurasidone for patients with schizophrenia following 6 weeks of acute treatment with lurasidone, olanzapine, or placebo: a 6-month, open-label, extension study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013 May;74(5):507-15. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08084. Epub 2013 Mar 13. PMID: 23541189.

103. Tandon R, Cucchiaro J, Phillips D, Hernandez D, Mao Y, Pikalov A, Loebel A. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized withdrawal study of lurasidone for the maintenance of efficacy in patients with schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2016 Jan;30(1):69-77. doi: 10.1177/0269881115620460. Epub 2015 Dec 8. PMID: 26645209; PMCID: PMC4717319.

104. Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Xu J, Sarma K, Pikalov A, Kane JM. Effectiveness of lurasidone vs. quetiapine XR for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a 12-month, double-blind, noninferiority study. Schizophr Res. 2013 Jun;147(1):95-102. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.03.013. Epub 2013 Apr 11. PMID: 23583011.

105. Correll CU, Findling RL, Tocco M, Pikalov A, Deng L, Goldman R. Safety and effectiveness of lurasidone in adolescents with schizophrenia: results of a 2-year, open-label extension study. CNS Spectr. 2022 Feb;27(1):118-128. doi: 10.1017/S1092852920001893. Epub 2020 Oct 20. Erratum in: CNS Spectr. 2022 Feb;27(1):129. doi: 10.1017/S1092852921000511. PMID: 33077012.

106. Suppes T, Silva R, Cucchiaro J, Mao Y, Targum S, Streicher C, Pikalov A, Loebel A. Lurasidone for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder With Mixed Features: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016 Apr 1;173(4):400-7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15060770. Epub 2015 Nov 10. PMID: 26552942.

107. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, third edition. 2020. Accessed 2024 Dec 11. https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890424841.

108. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DoD). VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of First-Episode Psychosis and Schizophrenia, 2023. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/scz/VA-DOD-CPG-Schizophrenia-CPG_Finalv231924.pdf

109. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry (Revision). 2002; 159:1-50

110. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DoD). VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Bipolar Disorder, 2023. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/bd/VA-DOD-CPG-BD-Full-CPGFinal508.pdf

111. Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). ISMP List of Confused Drug Names, ISMP; 2024.

Related/similar drugs

Frequently asked questions

- Can you stop taking Latuda immediately?

- Does Latuda make you sleepy?

- Is Latuda a mood stabilizer or an antipsychotic?

- How fast does Latuda work?

- Does Latuda cause weight gain?

- Can Latuda be cut in half or split?

- Is Latuda a controlled substance?

- What drugs cause tardive dyskinesia?

More about lurasidone

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (954)

- Drug images

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Support group

- Drug class: atypical antipsychotics

- Breastfeeding

- En español