Hydralazine / Hydrochlorothiazide Side Effects

Medically reviewed by Drugs.com. Last updated on Feb 23, 2025.

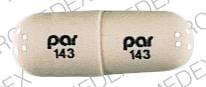

Applies to hydralazine / hydrochlorothiazide: oral capsule.

Important warnings

This medicine can cause some serious health issues

You should not use this medication if you are allergic to hydralazine (Apresoline) or hydrochlorothiazide, or if you have coronary artery disease, rheumatic heart disease affecting the mitral valve, or if you are unable to urinate.

Before using this medication, tell your doctor if you have liver disease, kidney disease, glaucoma, angina pectoris (chest pain), asthma or allergies, gout, lupus, diabetes, an allergy to sulfa drugs or penicillin, or if you have ever had a stroke.

Drinking alcohol can further lower your blood pressure and may increase certain side effects of hydrochlorothiazide and hydralazine.

Avoid becoming overheated or dehydrated during exercise and in hot weather. Follow your doctor's instructions about the type and amount of liquids you should drink. In some cases, drinking too much liquid can be as unsafe as not drinking enough.

There are many other drugs that can interact with hydrochlorothiazide and hydralazine.

Tell your doctor about all medications you use. This includes prescription, over-the-counter, vitamin, and herbal products.

Do not start a new medication without telling your doctor.

Keep a list of all your medicines and show it to any healthcare provider who treats you.

Keep using this medicine as directed, even if you feel well. High blood pressure often has no symptoms. You may need to use blood pressure medication for the rest of your life.

Get emergency medical help if you have any of these signs of an allergic reaction while taking hydralazine / hydrochlorothiazide: hives; difficulty breathing; swelling of your face, lips, tongue, or throat.

Stop using this medication and call your doctor at once if you have a serious side effect such as:

-

eye pain, vision problems;

-

dry mouth, thirst, nausea, vomiting;

-

feeling weak, drowsy, restless, or light-headed;

-

fast or uneven heart rate;

-

muscle pain or weakness;

-

confusion, unusual thoughts or behavior;

-

pale skin, easy bruising or bleeding;

-

painful or difficult urination;

-

urinating less than usual or not at all;

-

swelling in your face, stomach, hands, or feet;

-

numbness, burning, pain, or tingly feeling;

-

a red, blistering, peeling skin rash;

-

dark-colored urine, jaundice (yellowing of the skin or eyes); or

-

joint pain or swelling with fever, chest pain, weakness or tired feeling.

Less serious side effects of hydralazine / hydrochlorothiazide may include:

-

loss of appetite, diarrhea, constipation;

-

headache;

-

dizziness, spinning sensation;

-

blurred vision;

-

muscle or joint pain; or

-

mild itching or skin rash.

This is not a complete list of side effects and others may occur. Call your doctor for medical advice about side effects.

See also:

For healthcare professionals

Applies to hydralazine / hydrochlorothiazide: oral capsule.

Immunologic adverse events

Because up to 20% of patients who receive 400 mg or more of hydralazine per day develop a systemic lupus erythematosus syndrome, some experts recommend checking a patient's acetylator status before giving higher doses. Up to 70% of "resistant" patients are fast acetylators, in whom the dose can be relatively safely increased.

Data suggest that hydralazine lupus may represent a unique hypersensitivity reaction in which antibodies to native DNA occur. These antibodies are believed to account for the clinical similarities between hydralazine-induced lupus and systemic lupus erythematosus.[Ref]

Immunologic side effects including development of a lupus-like syndrome have been reported. This syndrome is more likely in patients who receive 400 mg or more of hydralazine per day, in female patients, or in patients who are slow acetylators. Of patients who receive less than 200 mg of hydralazine per day, 40% develop a positive ANA titer, and up to 6% develop a lupus-like syndrome. Of patients who receive 400 mg or more per day, 50% develop a positive ANA titer, and up to 14% develop a lupus-like syndrome.

The lupus syndrome may present as arthralgia (most common), myalgia, lethargy, malaise, a typical erythematous rash, weight loss, or dyspnea. The lupus syndrome may also be found incidentally in asymptomatic patients by urinalysis (proteinuria, hematuria), blood chemistry (elevated ESR, antinuclear antibody), or chest X-ray (interstitial lung disease, rare). Hypocomplementemia is an extremely rare finding in hydralazine-induced lupus.

Alternative therapy is recommended for patients who develop the clinical appearance of a lupus syndrome, sustained rises in the antinuclear antibody titer, or the presence of LE cells. The syndrome is reversible, but may take months to years to resolve.[Ref]

Cardiovascular

Cardiovascular side effects are related to hydralazine-induced peripheral vasodilation and HCTZ-induced decreased intravascular volume. Orthostatic hypotension, with or without reflex tachycardia, may occur resulting in syncope. This may be more likely in the elderly. Palpitations, flushing, edema, or chest pain are reported in less than 5% of patients. The use of hydralazine in patients with severe chronic heart failure is associated with ischemia, including episodes of myocardial infarction.

In patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hydralazine may increase pulmonary artery hypertension, especially during periods of hypoxia. The use of hydralazine in these patients may, on rare occasions, result in profound hypotension, tachycardia, and even death.

Rare cases of bradycardia or cardiac tamponade (associated with hydralazine-induced lupus) have been reported. Hydralazine does not have a deleterious effect on the lipid profile. In fact, hydralazine has been shown to decrease total and LDL cholesterol.[Ref]

Provocation of ischemia in patients with compromised left ventricular systolic function may be due to the inability of hydralazine to decrease preload, or left ventricular filling pressures.

The mechanism of increased pulmonary hypertension in patients with PH or COPD is a decrease of systemic vascular resistance accompanied by an increase in cardiac output without a fall in the pulmonary vascular resistance. In case reports and small series of patients with PH or COPD, the use of hydralazine resulted in palpitations, chest tightness, unchanged pulmonary vascular resistance, increased pulmonary artery pressure, decreased systemic vascular resistance, and increased heart rate and cardiac output. For this reason, many experts recommend hemodynamic monitoring during hydralazine therapy if hydralazine must be used in such patients.[Ref]

Metabolic

Metabolic side effects are common, especially when doses greater than 50 mg per day of HCTZ are used. Mild hypokalemia (decrease of 0.5 mEq/L) occurs in up to 50% of patients, and may predispose some patients to significant cardiac arrhythmias, including ventricular ectopy and complete AV heart block. Metabolic alkalosis, hyponatremia, hypomagnesemia, hypercalcemia, hyperglycemia, and elevated serum uric acid levels are also relatively common. HCTZ may increase serum cholesterol.[Ref]

Caution should be used in patients with hypercholesterolemia since HCTZ may increase total serum cholesterol by 11%, LDL lipoprotein cholesterol by 12%, and VLDL lipoprotein cholesterol levels by 50%.

Caution should also be used in diabetic patients since HCTZ may also reduce insulin secretion.

Hyperuricemia may be an important consideration in patients with a history of gout. Hypophosphatemia and low serum magnesium concentrations may occur but are usually clinically insignificant, except in malnourished patients.[Ref]

Nervous system

Nervous system side effects including peripheral neuropathy have been reported. Peripheral neuropathy is related to the dose hydralazine used and is more common in slow acetylators. The neuropathy usually first presents as paresthesias, numbness, and tingling in the extremities. Neuropathy is probably the result of pyridoxine deficiency, perhaps because the formation of a pyridoxal-hydralazine complex inactivates the coenzyme. This neuropathy can be treated by administration of pyridoxine. Headache or dizziness are reported in approximately 5% of patients. Rare cases of cerebrovascular insufficiency have been associated with HCTZ-induced plasma volume contraction.[Ref]

A 61-year-old man with hypertension developed ataxia, numbness, and lower extremity weakness approximately six months after beginning hydralazine (up to 300 mg per day) and reserpine therapy. The neuropathy partially resolved after reduction of the hydralazine dosage to 60 mg daily. A complete evaluation revealed that this man was a slow acetylator of hydralazine.[Ref]

Hypersensitivity

Hypersensitivity reactions are rarely associated with either drug. Anaphylaxis associated with HCTZ has been reported. Syndromes consisting of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and rash, occur in less than 1% of patients. Rare cases of hepatitis, retroperitoneal fibrosis, and occupational asthma associated with hydralazine have been reported. Rare cases of acute pulmonary edema, interstitial cystitis, and interstitial nephritis associated with HCTZ have been reported.[Ref]

A 44-year-old woman with hypertension and acute sinusitis developed acute renal failure, edema, and a generalized maculopapular erythematous rash during therapy with ampicillin, hydralazine, and HCTZ. A complete evaluation revealed bilateral hydronephrosis and hydroureters secondary to ureteral obstruction due to retroperitoneal fibrosis. Renal function returned to baseline after oral prednisone therapy. It is unclear whether this problem was due to one or more of her medications.

A 68-year-old man with a history of myocardial infarction (MI) developed dyspnea, chest tightness, a low grade fever, dizziness, sweating, vomiting associated with cyanosis, a mild leukocytosis, radiographic evidence of pulmonary edema, clinical evidence of hypovolemia, and respiratory acidosis. MI and infection were ruled out. The patient recovered after restoration of his intravascular volume with saline and albumin. The only precipitating factor per history was the ingestion of HCTZ, which the patient had taken without incident for two years. Rechallenge resulted in recurrent acute pulmonary edema. Other signs of hypersensitivity, such as rash and eosinophilia, were absent.[Ref]

Hematologic

A 71-year-old man with hypertension developed anorexia, weight loss, petechia, and microcytic anemia during therapy with hydralazine and oxprenolol. Evaluation for iron deficiency, hemolysis, or marrow depression was negative. The patient was found to have fecal blood loss, anti-DNA antibodies, decreased complement levels, a normal upper GI series, and biopsy-proven vasculitis. The syndrome resolved within two weeks after discontinuation of hydralazine.

There are rare case reports of HCTZ-induced immune hemolytic anemia. The following illustrates a fatal case:

A 53-year-old man with hypertension developed nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and progressive anorexia and weakness associated with scleral icterus, anemia with spherocytosis, dark red urine with proteinuria, bilirubinuria, and hemoglobinuria, and elevated lactic dehydrogenase levels 18 months after beginning HCTZ and methyldopa. Haptoglobin was less than 50 mg per dl. Direct and indirect Coombs tests were positive. The patient died suddenly; autopsy revealed no obvious cause of death, left ventricular hypertrophy, and mild coronary atherosclerosis.[Ref]

Hematologic abnormalities are associated with the hydralazine-induced lupus-like syndrome. Anemia may be caused by one of at least four hydralazine-associated problems including hemolysis, the formation of a circulating anticoagulant, thrombocytopenia, and vasculitis. Rare cases of leukopenia, agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, and thrombocytopenia have been associated with either drug.[Ref]

Dermatologic

A 65-year-old man with ischemic cardiomyopathy developed a pruritic, erythematous, generalized rash within two months after beginning hydralazine (200 mg per day) therapy. There were no clinical or laboratory signs of lupus. The rash persisted upon gradual withdrawal of the patient's other medications, but cleared only after discontinuation of hydralazine. Rechallenge resulted in a recurrent pruritic rash.

A 67-year-old white woman with hypothyroidism, hypercalcemia, depression, and hypertension developed facial erythema, headaches, tremors, confusion, and personality changes associated with a new positive ANA and anti-nRNP, and skin biopsy consistent with lupus erythematosus while taking HCTZ, levothyroxine, and amitriptyline. The eruption resolved upon discontinuation of HCTZ, but she later developed a higher ANA titer associated with symptomatic diffuse interstitial pulmonary infiltrates. She was successfully treated with corticosteroids.[Ref]

Dermatologic manifestations of the hydralazine-induced lupus-like syndrome include cutaneous vasculitis. In addition, a rare, distinct entity with clinical and laboratory features indistinguishable from those of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus has been associated with HCTZ. Two cases of Sweet's syndrome (neutrophilic dermatosis) have been associated with hydralazine. Erythema annular centrifugum, acute eczematous dermatitis, morbilliform and leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and phototoxic dermatitis have been associated with HCTZ.[Ref]

Renal

In one study, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN) was described in 4 of 444 patients, all of whom were men who were treated for 5 to 11 years with daily hydralazine doses of 100 to 250 mg. In three of the four cases, biopsy revealed a focal and segmental glomerular necrosis with crescents and positive immunofluorescence. The antinuclear antibody titer became positive in three. Renal function improved in all but one after the withdrawal of hydralazine and institution of corticosteroid therapy. A number of other cases of RPGN are reported. It appears to be far more common in patients who are slow acetylators.

Although HCTZ has been used to treat nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, a case report in which the drug was believed to have caused this condition has been reported.[Ref]

Renal side effects are common in idiopathic systemic lupus erythematosus; however, immune complex glomerulonephritis is rare in drug-induced lupus. Rare cases of rapidly progressive and focal glomerulonephritis associated with the hydralazine-induced lupus syndrome are often accompanied by anemia, a positive anti-DNA antibody titer, and a positive ANA titer. New or worsened renal insufficiency may occur due to HCTZ-induced intravascular volume depletion. Rare cases of interstitial nephritis have been reported.[Ref]

Respiratory

A 48-year-old woman with hypertension developed dyspnea, hemoptysis, pleurisy, proteinuria, and hematuria one year after beginning hydralazine (150 mg per day), polythiazide, and atenolol therapy. Other associated findings included an elevated ESR, antinuclear factor, anti-DNA titer, a positive LE test, and radiographic findings of diffuse interstitial lung disease. Two weeks after stopping hydralazine, the signs and symptoms of lupus with pulmonary involvement disappeared.[Ref]

Respiratory side effects include nasal stuffiness, seen in approximately 3% of patients who are taking hydralazine. There are approximately 30 case reports of acute noncardiogenic pulmonary edema associated with HCTZ and rare cases of "hydralazine lung," associated with hydralazine-induced lupus.[Ref]

Endocrine

Endocrinologic problems associated with thiazide diuretics include glucose intolerance and a potentially deleterious effect on the lipid profile. This may be important in some patients with or who are at risk for diabetes or coronary artery disease.[Ref]

A prospective study of 34 patients who received oral thiazide diuretics for 14 years without interruption revealed an increased mean fasting blood glucose level after treatment. Withdrawal of thiazide therapy for seven months in 10 of the patients resulted in average reductions of 10% in fasting blood glucose and 25% in the 2-hour glucose tolerance test value. A control group was not reported.[Ref]

Gastrointestinal

Gastrointestinal side effects are unusual, and include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. There are rare cases of pancreatitis and acute cholecystitis associated with HCTZ.[Ref]

Thiazide diuretics may increase serum cholesterol and triglycerides, resulting in increased risk of cholesterol gallstone formation. Reports of bowel strictures associated with thiazide ingestion have been reported in the 1960's, although these patients were on a combination HCTZ-potassium product.[Ref]

Genitourinary

Genitourinary side effects including Impotence is a rare complaint among male patients taking hydralazine.[Ref]

At least two cases of male impotence associated with hydralazine have been reported. The mechanism is unclear. There was no evidence of a neuropathy in either case.[Ref]

Hepatic

Hepatic reactions are rare. Less than ten cases of hepatitis are associated with hydralazine, many of which are believed to be due to hypersensitivity. Histological findings include hepatocellular, cholestatic, mixed hepatocellular-cholestatic, and granulomatous patterns.[Ref]

A 59-year-old woman with hypertension and cholecystic gallbladder disease developed abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, painful hepatomegaly, elevated serum transaminases, direct hyperbilirubinemia, and liver biopsy findings of subacute hepatitis (with bridging necrosis) within two days after hydralazine was added to her medical regimen. The signs and symptoms of hepatitis resolved after all medications were withheld, but returned upon rechallenge with hydralazine.[Ref]

References

1. Hahn BH, Sharp GC, Irvin WS, et al. (1972) "Immune responses to hydralazine and nuclear antigens in hydralazine-induced lupus erythematosus." Ann Intern Med, 76, p. 365-74

2. Carey RM, Coleman M, Feder A (1973) "Pericardial tamponade: a major presenting manifestation of hydralazine-induced lupus syndrome." Am J Med, 54, p. 84-7

3. Perry HM (1973) "Late toxicity to hydralazine resembling systemic lupus erythematosus or rheumatoid arthritis." Am J Med, 54, p. 58-72

4. Blumenkrantz N, Christiansen AH, Ullman S, Asboe-Hansen G (1974) "Hydralazine-induced lupoid syndrome." Acta Med Scand, 195, p. 443-9

5. Koch-Weser J (1976) "Hydralazine." N Engl J Med, 295, p. 320-3

6. Weinstein J (1978) "Hypocomplementemia in hydralazine-associated systemic lupus erythematosus." Am J Med, 65, p. 553-6

7. Bernstein RM, Egerton-Vernon J, Webster J (1980) "Hydrallazine-induced cutaneous vasculitis." Br Med J, 280, p. 156-7

8. Brooks AP, Paulley JW (1980) "Cutaneous manifestations of hydrallazine toxicity." Br Med J, 02/16/80, p. 482

9. Bass BH (1981) "Hydralazine lung." Thorax, 36, p. 695-6

10. Finlay AY, Statham B, Knight AG (1981) "Hydrallazine-induced necrotising vasculitis." Br Med J, 282, p. 1703-4

11. Peacock A, Weatherall D (1981) "Hydralazine-induced necrotising vasculitis." Br Med J, 282, p. 1121-2

12. Ludmerer KM, Kissane JM (1981) "Clinopathologic conference: renal failure, dyspnea and anemia in a 57 year old woman." Am J Med, 71, p. 876-86

13. Freestone S, Ramsay LE (1982) "Transient monoclonal gammopathy in hydralazine-induced lupus erythematosus." Br Med J, 285, p. 1536-7

14. Kincaid-Smith P, Whitworth JA (1983) "Hydralazine-associated glomerulonephritis." Lancet, 2, p. 348

15. Ihle BU, Whitworth JA, Dowling JP, Kincaid-Smith P (1984) "Hydralazine and lupus nephritis." Clin Nephrol, 22, p. 230-8

16. Cameron HA, Ramsay LE (1984) "The lupus syndrome induced by hydralazine: a common complication with low dose treatment." Br Med J, 289, p. 410-12

17. Naparstek Y, Kopolovic J, Tur-Kaspa R, Rubinger D (1984) "Focal glumerulonephritis in the course of hydralazine-induced lupus syndrome." Arthritis Rheum, 27, p. 822-5

18. Shapiro KS, Pinn VW, Harrington JT, Levey AS (1984) "Immune complex glomerulonephritis in hydralazine-induced SLE." Am J Kidney Dis, 3, p. 270-4

19. Cush JJ, Goldings EA (1985) "Southwestern internal medicine conference: drug-induced lupus: clinical spectrum and pathogenesis." Am J Med Sci, 290, p. 36-45

20. Bjorck S, Svalander C, Westberg G (1985) "Hydralazine-associated glomerulonephritis." Acta Med Scand, 218, p. 261-9

21. Innes A, Rennie JA, Cato GR (1986) "Drug-induced lupus caused by very-low-dose hydralazine." Br J Rheumatol, 25, p. 225-31

22. Sequeira W, Polisky RB, Alrenga DP (1986) "Neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet's Syndrome)." Am J Med, 81, p. 558-60

23. Widgren B, Berglund G, Andersson OK (1986) "Side-effects in long-term treatment with hydralazine." Acta Med Scand, 714, p. 193-6

24. Darwaza A, Lamey P-J, Connell JM (1988) "Hydrallazine-induced Sjogren's syndrome." Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 17, p. 92-3

25. Sturman SG, Kumararatne D, Beevers DG (1988) "Fatal hydralazine-induced systemic lupus erythematosus." Lancet, 12/03/88, p. 1304

26. Fleming MG, Bergfeld WF, Tomecki KJ, et al. (1989) "Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus." Int J Dermatol, 28, p. 321-6

27. Ramsey-Goldman R, Franz T, Solano FX, Medsger TA (1990) "Hydralazine induced lupus and sweet's syndrome: report and review of the literature." J Rheumatol, 17, p. 682-4

28. Bjornberg A, Gisslen H (1965) "Thiazides: A cause of necrotising vasculitis?" Lancet, 2, p. 982-3

29. Beck ML, Cline JF, Hardman JT, Racela LS, Davis JW (1984) "Fatal intravascular immune hemolysis induced by hydrochlorothiazide." Am J Clin Pathol, 81, p. 791-4

30. Reed BR, Huff JC, Jones SK, Orton PW, Lee LA, Norris DA (1985) "Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus associated with hydrochlorothiazide therapy." Ann Intern Med, 103, p. 49-51

31. Shirey RS, Bartholomew J, Bell W, Pollack B, Kickler TS, Ness PM (1988) "Characterization of antibody and selection of alternative drug therapy in hydrochlorothiazide-induced immune hemolytic anemia." Transfusion, 28, p. 70-2

32. Lunde PK, Frislid K, Hansteen V (1977) "Disease and acetylation polymorphism." Clin Pharmacokinet, 2, p. 182-97

33. Timbrell JA, Facchini V, Harland SJ, Mansilla-Tinoco R (1984) "Hydralazine-induced lupus: is there a toxic metabolic pathway?" Eur J Clin Pharmacol, 27, p. 555-9

34. Miller AJ, Abrams DL, Kaplan BM (1975) "Persistent reversal of severe systemic hypertension after prolonged toxic reaction to hydralazine." Cardiology, 60, p. 251-6

35. Talseth T (1977) "Kinetics of hydralazine elimination." Clin Pharmacol Ther, 21, p. 715-20

36. Laslett LJ, DeMaria AN, Amsterdam EA, Mason DT (1978) "Hydralazine-induced tachycardia and sodium retention in heart failure: hemodynamic and symptomatic correlation by prazosin therapy." Arch Intern Med, 138, p. 819-20

37. Wehner RJ, Romanauskas VS (1981) "An adverse reaction with hydralazine: a case study." AANA J, June, p. 274-5

38. Packer M, Meller J, Medina N, et al. (1981) "Provocation of myocardial ischemic events during initiation of vasodilator therapy for severe chronic heart failure." Am J Cardiol, 48, p. 939-46

39. Packer M, Greenberg B, Massie B, Dash H (1982) "Deleterious effects of hydralazine in patients with pulmonary hypertension." N Engl J Med, 306, p. 1326-31

40. Kronzon I, Cohen M, Winer HE (1982) "Adverse effect of hydralazine in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension." JAMA, 247, p. 3112-4

41. Danielson M, Kjellberg J, Ohman P, Wernersson B (1983) "Evaluation of once daily hydralazine in inadequately controlled hypertension." Acta Med Scand, 214, p. 373-80

42. Fagan TC, Sternleib C, Vlachakis N, et al. (1984) "Efficacy and safety comparison of nitrendipine and hydralazine as antihypertensive monotherapy." J Cardiovasc Pharmacol, 6, s1109-13

43. Tuxen DV, Powles AC, Mathur PN, et al. (1984) "Detrimental effects of hydralazine in patients with chronic air-flow obstruction and pulmonary hypertension." Am Rev Respir Dis, 129, p. 388-95

44. Keller CA, Shepard JW, Chun DS, et al. (1984) "Effects of hydralazine on hemodynamics, ventilation, and gas exchange in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pulmonary hypertension." Am Rev Respir Dis, 129, p. 606-11

45. Williams LL, Lopez LM, Thorman AD, et al. (1988) "Plasma lipid profiles and antihypertensive agents: effects of lisinopril, enalapril, nitrendipine, hydralazine, and hydrochlorothiazide." Drug Intell Clin Pharm, 22, p. 546-50

46. Hammond TG, Mosesson MW (1989) "Fatal small-bowel necrosis and pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease." Arch Intern Med, 149, p. 447-8

47. Lodeiro JG, Feinstein SJ, Lodeiro SB (1989) "Fetal premature atrial contractions associated with hydralazine." Am J Obstet Gynecol, 160, p. 105-7

48. Aylward PE, Tonkin AM (1982) "Cardiac tamponade in hydrallazine-induced systemic lupus erythematosus." Aust N Z J Med, 12, p. 546

49. Papademetriou V, Fletcher R, Khatri IM, Freis ED (1983) "Diuretic-induced hypokalemia in uncomplicated systemic hypertension: effect of plasma potassium correction on cardiac arrhythmias." Am J Cardiol, 52, p. 1017-22

50. Ragnarsson J, Hardarson T, Snorrason SP (1987) "Ventricular dysrhythmias in middle-aged hypertensive men treated either with a diuretic agent or a beta-blocker." Acta Med Scand, 221, p. 143-8

51. Hollifield JW, Slaton PE (1981) "Thiazide diuretics, hypokalemia and cardiac arrhythmias." Acta Med Scand Suppl, 647, p. 67-73

52. Krishna GG, Narins RG (1988) "Hemodynamic consequences of diuretic-induced hypokalemia." Am J Kidney Dis, 12, p. 329-31

53. Mahabir RN, Laufer ST (1969) "Clinical evaluation of diuretics in congestive heart failure. A detailed study in four patients." Arch Intern Med, 124, p. 1-7

54. Holland OB, Kuhnert L, Pollard J, Padia M, Anderson RJ, Blomqvist G (1988) "Ventricular ectopic activity with diuretic therapy." Am J Hypertens, 1, p. 380-5

55. Mouallem M, Friedman E, Shemesh Y, Mayan H, Pauzner R, Farfel Z (1991) "Cardiac conduction defects associated with hyponatremia." Clin Cardiol, 14, p. 165-8

56. Grunwald MH, Halevy S, Livni E (1989) "Allergic vasculitis induced by hydrochlorothiazide: confirmation by mast cell degranulation test." Isr J Med Sci, 25, p. 572-4

57. Lins L-E, Berglund J, Eliasson K, Wernersson B (1983) "Efficacy and tolerability of hydralazine, in conventional and slow-release preparations, during long-term treatment of primary hypertension." Clin Ther, 5, p. 251-9

58. Rosenberg L, Shapiro S, Slone D, Kaufman DW, Miettinen OS, Stolley PD (1980) "Thiazides and acute cholecystitis." N Engl J Med, 303, p. 546-8

59. Kuller L, Farrier N, Caggiula A, Borhani N, Dunkle S (1985) "Relationship of diuretic therapy and serum magnesium levels among participants in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial." Am J Epidemiol, 122, p. 1045-59

60. Fichman MP, Vorherr H, Kleeman CR, Telfer N (1971) "Diuretic-induced hyponatremia." Ann Intern Med, 75, p. 853-63

61. Papademetriou V, Price M, Notargiacomo A, Gottdiener J, Fletcher RD, Freis ED (1985) "Effect of diuretic therapy on ventricular arrhythmias in hypertensive patients with or without left ventricular hypertrophy." Am Heart J, 110, p. 595-9

62. Polanska AI, Baron DN (1978) "Hyponatraemia associated with hydrochlorothiazide treatment ." Br Med J, 1, p. 175-6

63. Pinnock CA (1978) "Hyponatraemia associated with hydrochlorothiazide treatment ." Br Med J, 1, p. 48

64. Hakim R, Tolis G, Goltzman D, Meltzer S, Friedman R (1979) "Severe hypercalcemia associated with hydrochlorothiazide and calcium carbonate therapy." Can Med Assoc J, 121, p. 591-4

65. Byatt CM, Millard PH, Levin GE (1990) "Diuretics and electrolyte disturbances in 1000 consecutive geriatric admissions." J R Soc Med, 83, p. 704-8

66. Bain PG, Egner W, Walker PR (1986) "Thiazide-induced dilutional hyponatraemia masquerading as subarachnoid haemorrhage ." Lancet, 2, p. 634

67. Benfield GF, Haffner C, Harris P, Stableforth DE (1986) "Dilutional hyponatraemia masquerading as subarachnoid haemorrhage in patient on hydrochlorothiazide/amiloride/timolol combined drug ." Lancet, 2, p. 341

68. Duarte CG, Winnacker JL, Becker KL, Pace A (1971) "Thiazide-induced hypercalcemia." N Engl J Med, 284, p. 828-30

69. Gould L, Reddy CV, Zen B, Singh BK (1980) "Life-threatening reaction to thiazides." N Y State J Med, 80, p. 1975-6

70. Diamond MT (1972) "Hyperglycemic hyperosmolar coma associated with hydrochlorothiazide and pancreatitis." N Y State J Med, 72, p. 1741-2

71. Klimiuk PS, Davies M, Adams PH (1981) "Primary hyperparathyroidism and thiazide diuretics." Postgrad Med J, 57, p. 80-3

72. Seelig CB (1990) "Magnesium deficiency in two hypertensive patient groups." South Med J, 83, p. 739-42

73. Peters RW, Hamilton J, Hamilton BP (1989) "Incidence of cardiac arrhythmias associated with mild hypokalemia induced by low-dose diuretic therapy for hypertension." South Med J, 82, 966-9,

74. Kone B, Gimenez L, Watson AJ (1986) "Thiazide-induced hyponatremia." South Med J, 79, p. 1456-7

75. Fager G, Berglund G, Bondjers G, Elmfeldt D, Lager I, Olofsson SO, Smith U, Wiklund O (1983) "Effects of anti-hypertensive therapy on serum lipoproteins. Treatment with metoprolol, propranolol and hydrochlorothiazide." Artery, 11, p. 283-96

76. Jones IG, Pickens PT (1967) "Diabetes mellitus following oral diuretics." Practitioner, 199, p. 209-10

77. Murphy MB, Kohner E, Lewis PJ, Schumer B, Dollery CT (1982) "Glucose intolerance in hypertensive patients treated with diuretics: a fourteen-year follow-up." Lancet, 2, p. 1293-5

78. Bell DS (1993) "Insulin resistance. An often unrecognized problem accompanying chronic medical disorders." Postgrad Med, 93, 99-103,

79. Berlin I (1993) "Prazosin, diuretics, and glucose intolerance." Ann Intern Med, 119, p. 860

80. Tsujimoto G, Horai Y, Ishizaki T, Itoh K (1981) "Hydralazine-induced peripheral neuropathy seen in a Japanese slow acetylator patient." Br J Clin Pharmacol, 11, p. 622-5

81. Young EJ, Fainstein V, Musher DM (1982) "Drug-induced fever: cases seen in the evaluation of unexplained fever in a general hospital population." Rev Infect Dis, 4, p. 69-77

82. Schapel GJ (1984) "Skin rash and hydralazine." Med J Aust, 141, p. 765-6

83. Waters VV (1989) "Hydralazine, hydrochlorothiazide and ampicillin associated with retroperitoneal fibrosis: case report." J Urol, 141, p. 936-7

84. Perrin B, Malo J-L, Cartier A, et al. (1990) "Occupational asthma in a pharmaceutical worker exposed to hydralazine." Thorax, 45, p. 980-1

85. Magil AB, Ballon HS, Cameron EC, Rae A (1980) "Acute interstitial nephritis associated with thiazide diuretics. Clinical and pathologic observations in three cases." Am J Med, 69, p. 939-43

86. Hoss DM, Nierenberg DW (1988) "Severe shaking chills and fever following hydrochlorothiazide administration." Am J Med, 85, p. 747

87. Klein MD (1987) "Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema following hydrochlorothiazide ingestion." Ann Emerg Med, 16, p. 901-3

88. Beaudry C, Laplante L (1973) "Severe allergic pneumonitis from hydrochlorothiazide." Ann Intern Med, 78, p. 251-3

89. Hoegholm A, Rasmussen SW, Kristensen KS (1990) "Pulmonary oedema with shock induced by hydrochlorothiazide: a rare side effect mimicking myocardial infarction." Br Heart J, 63, p. 186

90. Biron P, Dessureault J, Napke E (1991) "Acute allergic interstitial pneumonitis induced by hydrochlorothiazide [published erratum appears in Can Med Assoc J 1991 Sep 1;145(5):391]." Can Med Assoc J, 145, p. 28-34

91. Dorn MR, Walker BK (1981) "Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema associated with hydrochlorothiazide therapy." Chest, 79, p. 482-3

92. Magil AB (1983) "Drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis with granulomas." Hum Pathol, 14, p. 36-41

93. Prupas HM, Brown D (1983) "Acute idiosyncratic reaction to hydrochlorothiazide ingestion." West J Med, 138, p. 101-2

94. Grace AA, Morgan AD, Strickland NH (1989) "Hydrochlorothiazide causing unexplained pulmonary oedema." Br J Clin Pract, 43, p. 79-81

95. Levay ID (1984) "Hydrochlorothiazide-induced pulmonary edema." Drug Intell Clin Pharm, 18, p. 238-9

96. Goette DK, Beatrice E (1988) "Erythema annulare centrifugum caused by hydrochlorothiazide-induced interstitial nephritis." Int J Dermatol, 27, p. 129-30

97. Alted E, Navarro M, Cantalapiedra JA, Alvarez JA, Blasco MA, Nunez A (1987) "Non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema after oral ingestion of hydrochlorothiazide ." Intensive Care Med, 13, p. 364-5

98. Orenstein AA, Yakulis V, Eipe J, Costea N (1977) "Immune hemolysis due to hydralazine." Ann Intern Med, 86, p. 450-1

99. Widerlov E, Karlman I, Storsater J (1980) "Hydralazine-induced neonatal thrombocytopenia." N Engl J Med, 303, p. 1235

100. Macleod WN (1983) "Anaemia in the hydrallazine-induced lupus syndrome." Scott Med J, 28, p. 181-2

101. Garratty G, Houston M, Petz LD, Webb M (1981) "Acute immune intravascular hemolysis due to hydrochlorothiazide." Am J Clin Pathol, 76, p. 73-8

102. Eisner EV, Crowell EB (1971) "Hydrochlorothiazide-dependent thrombocytopenia due to IgM antibody." JAMA, 215, p. 480-2

103. Diffey BL, Langtry J (1989) "Phototoxic potential of thiazide diuretics in normal subjects." Arch Dermatol, 125, p. 1355-8

104. Robinson HN, Morison WL, Hood AF (1985) "Thiazide diuretic therapy and chronic photosensitivity." Arch Dermatol, 121, p. 522-4

105. Parodi A, Romagnoli M, Rebora A (1989) "Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus-like eruption caused by hydrochlorothiazide." Photodermatol, 6, p. 100-2

106. Goodrich AL, Kohn SR (1993) "Hydrochlorothiazide-induced lupus erythematosus: a new variant?" J Am Acad Dermatol, 28, p. 1001-2

107. Delevett AF, Recalde M (1973) "Diuretic-induced renal colic." JAMA, 225, p. 992

108. Balizet L (1973) "Recurrent parathyroid adenoma. Association with prolonged thiazide administration." JAMA, 225, p. 1238-9

109. Dietz MW (1967) "Iatrogenic jejunal ulcer." Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med, 99, p. 136-8

110. Reinus FZ, Weinberger HA, Fischer WW (1966) "Medication-induced ulceration of the small bowel." Am J Surg, 112, p. 97-101

111. Wagner W, Longerbeam JK, Smith LL, Feikes HL (1967) "Drug-induced ulcers of the small bowel causing intestinal obstruction or perforation." Am Surg, 33, p. 7-11

112. Campbell JR, Knapp RW (1966) "Small bowel ulceration associated with thiazide and potassium therapy: review of 13 cases." Ann Surg, 163, p. 291-6

113. Smith BL, Tedeschi A, Lane CD (1988) "Pancreatitis with a twist." Hosp Pract (Off Ed), 23, 150,

114. Holland GW (1965) "Stenosing ulcers of the small bowel associated with thiazide and potassium therapy." N Z Med J, 64, p. 383-5

115. Keidan H (1976) "Impotence during antihypertensive treatment." Can Med Assoc J, 114, p. 874

116. Jori GP, Peschle C (1973) "Hydralazine disease associated with transient granulomas in the liver." Gastroenterology, 64, p. 1163-7

117. Bartoli E, Massarelli G, Solinas A, et al. (1979) "Acute hepatitis with bridging necrosis due to hydralazine intake." Arch Intern Med, 139, p. 698-9

118. Forster HS (1980) "Hepatitis from hydralazine." N Engl J Med, 303, p. 1362

119. Itoh S, Yamaba Y, Ichinoe A, Tsukada Y (1980) "Hydralazine-induced liver injury." Dig Dis Sci, 25, p. 884-7

120. Barnett DB, Hudson SA, Golightly PW (1980) "Hydralazine-induced hepatitis." Br Med J, 05/10/80, p. 1165-6

121. Stewart GW, Peart WS, Boylston AW (1981) "Obstructive jaundice, pancytopenia and hydralazine." Lancet, 05/30/81, p. 1207

122. Rice D, Burdick CO (1983) "Granulomatous hepatitis from hydralazine therapy." Arch Intern Med, 143, p. 1077

123. Myers JL, Augur NA (1984) "Hydralazine-induced cholangitis." Gastroenterology, 87, p. 1185-8

More about hydralazine / hydrochlorothiazide

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Drug images

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: miscellaneous antihypertensive combinations

Patient resources

Other brands

Related treatment guides

Further information

Hydralazine/hydrochlorothiazide side effects can vary depending on the individual. Always consult your healthcare provider to ensure the information displayed on this page applies to your personal circumstances.

Note: Medication side effects may be underreported. If you are experiencing side effects that are not listed, submit a report to the FDA by following this guide.