Indapamide

Drug class: Thiazide-like Diuretics

VA class: CV701

Chemical name: 3-(Aminosulfonyl)-4-chloro-N-(2,3-dihydro-2-methyl-1H-indol-1-yl)benzamide

Molecular formula: C16H16ClN3O3S

CAS number: 26807-65-8

Introduction

An indoline diuretic and antihypertensive agent; pharmacologically similar to thiazide diuretics.83

Uses for Indapamide

Hypertension

Used alone or in combination with other antihypertensive agents for all stages of hypertension.4 19 21 83 a

Classified as a thiazide-like drug with regard to management of hypertension; the drug’s efficacy in hypertensive patients is similar to that of the thiazide diuretics.14 18 21 24 501 1200

Thiazide-type diuretics are recommended as one of several preferred agents for the initial management of hypertension according to current evidence-based hypertension guidelines; other preferred options include ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, and calcium-channel blockers.502 503 504 1200 While there may be individual differences with respect to recommendations for initial drug selection and use in specific patient populations, current evidence indicates that these antihypertensive drug classes all generally produce comparable effects on overall mortality and cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and renal outcomes.501 502 504 1200

Individualize choice of therapy; consider patient characteristics (e.g., age, ethnicity/race, comorbidities, cardiovascular risk) as well as drug-related factors (e.g., ease of administration, availability, adverse effects, cost).501 502 503 504 515 1200 1201

A 2017 ACC/AHA multidisciplinary hypertension guideline classifies BP in adults into 4 categories: normal, elevated, stage 1 hypertension, and stage 2 hypertension.1200 (See Table 1.)

Source: Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13-115.

Individuals with SBP and DBP in 2 different categories (e.g., elevated SBP and normal DBP) should be designated as being in the higher BP category (i.e., elevated BP).

|

Category |

SBP (mm Hg) |

DBP (mm Hg) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Normal |

<120 |

and |

<80 |

|

Elevated |

120–129 |

and |

<80 |

|

Hypertension, Stage 1 |

130–139 |

or |

80–89 |

|

Hypertension, Stage 2 |

≥140 |

or |

≥90 |

The goal of hypertension management and prevention is to achieve and maintain optimal control of BP.1200 However, the BP thresholds used to define hypertension, the optimum BP threshold at which to initiate antihypertensive drug therapy, and the ideal target BP values remain controversial.501 503 504 505 506 507 508 515 523 526 530 1200 1201 1207 1209 1222 1223 1229

The 2017 ACC/AHA hypertension guideline generally recommends a target BP goal (i.e., BPs to achieve with drug therapy and/or nonpharmacologic intervention) <130/80 mm Hg in all adults regardless of comorbidities or level of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.1200 In addition, an SBP goal of <130 mm Hg generally is recommended for noninstitutionalized ambulatory patients ≥65 years of age with an average SBP of ≥130 mm Hg.1200 These BP goals are based upon clinical studies demonstrating continuing reduction of cardiovascular risk at progressively lower levels of SBP.1200 1202 1210

Previous hypertension guidelines generally have based target BP goals on age and comorbidities.501 504 536 Guidelines such as those issued by the JNC 8 expert panel generally have targeted a BP goal of <140/90 mm Hg regardless of cardiovascular risk and have used higher BP thresholds and target BPs in elderly patients compared with501 504 536 those recommended by the 2017 ACC/AHA hypertension guideline.1200

Some clinicians continue to support previous target BPs recommended by JNC 8 due to concerns about the lack of generalizability of data from some clinical trials (e.g., SPRINT study) used to support the current ACC/AHA hypertension guideline and potential harms (e.g., adverse drug effects, costs of therapy) versus benefits of BP lowering in patients at lower risk of cardiovascular disease.1222 1223 1224 1229

Consider potential benefits of hypertension management and drug cost, adverse effects, and risks associated with the use of multiple antihypertensive drugs when deciding a patient's BP treatment goal.1200 1220 1229

For decisions regarding when to initiate drug therapy (BP threshold), the current ACC/AHA hypertension guideline incorporates underlying cardiovascular risk factors.1200 ASCVD risk assessment recommended by ACC/AHA for all adults with hypertension.1200

ACC/AHA currently recommend initiation of antihypertensive drug therapy in addition to lifestyle/behavioral modifications at an SBP ≥140 mm Hg or DBP ≥90 mm Hg in adults who have no history of cardiovascular disease (i.e., primary prevention) and a low ASCVD risk (10-year risk <10%).1200

For secondary prevention in adults with known cardiovascular disease or for primary prevention in those at higher risk for ASCVD (10-year risk ≥10%), ACC/AHA recommend initiation of antihypertensive drug therapy at an average SBP ≥130 mm Hg or an average DBP ≥80 mm Hg.1200

Adults with hypertension and diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease (CKD), or age ≥65 years of age are assumed to be at high risk for cardiovascular disease; ACC/AHA state that such patients should have antihypertensive drug therapy initiated at a BP ≥130/80 mm Hg.1200 Individualize drug therapy in patients with hypertension and underlying cardiovascular or other risk factors.502 1200

In stage 1 hypertension, experts state that it is reasonable to initiate drug therapy using the stepped-care approach in which one drug is initiated and titrated and other drugs are added sequentially to achieve the target BP.1200 Initiation of antihypertensive therapy with 2 first-line agents from different pharmacologic classes recommended in adults with stage 2 hypertension and average BP >20/10 mm Hg above BP goal.1200

Black hypertensive patients generally tend to respond better to monotherapy with thiazide diuretics or calcium-channel blockers than to other antihypertensive drug classes (e.g., ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists).82 200 501 504 1200 However, the combination of an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor antagonist with a calcium-channel blocker or thiazide diuretic produces similar BP lowering in black patients as in other racial groups.1200

Thiazide-like diuretics may be preferred in hypertensive patients with osteoporosis. Secondary beneficial effect in hypertensive geriatric patients of reducing the risk of osteoporosis secondary to effect on calcium homeostasis and bone mineralization.

Edema in Heart Failure

Management of edema and salt retention associated with heart failure.21 24 29 39 83

Most experts state that all patients with symptomatic heart failure who have evidence for, or a history of, fluid retention generally should receive diuretic therapy in conjunction with moderate sodium restriction, an agent to inhibit the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAA) system (e.g., ACE inhibitor, angiotensin II receptor antagonist, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor [ARNI]), a β-adrenergic blocking agent (β-blocker), and in selected patients, an aldosterone antagonist.524 700 713

Diuretics produce rapid symptomatic benefits, relieving pulmonary and peripheral edema more rapidly (within hours or days) than cardiac glycosides, ACE inhibitors, or β-blockers (in weeks or months).70

Loop diuretics (e.g., bumetanide, ethacrynic acid, furosemide, torsemide) are diuretics of choice for most patients with heart failure.524

Edema in Pregnancy

Diuretics should not be used for routine therapy in pregnant women with mild edema who are otherwise healthy.a

Use of thiazide-like diuretics may be appropriate in the management of edema of pathologic origin during pregnancy when clearly needed; routine use of diuretics in otherwise healthy pregnant women is irrational.21 30

Use of diuretics for the management of edema of physiologic and mechanical origin during pregnancy generally is not warranted.21 30

Dependent edema secondary to restriction of venous return by the expanded uterus should be managed by elevating the lower extremities and/or by wearing support hose; use of diuretics in these pregnant women is inappropriate.21 30

In rare cases when the hypervolemia associated with normal pregnancy results in edema that produces extreme discomfort, a short course of diuretic therapy may provide relief and may be considered when other methods (e.g., decreased sodium intake, increased recumbency) are ineffective.21 30 44

Diuretics will not prevent the development of toxemia, nor is there evidence that diuretics have a beneficial effect on the overall course of established toxemia.21 30

Edema (General)

Management of edema resulting from various causes†.24 29 39

No substantial difference in clinical effects or toxicity of comparable thiazide or thiazide-like diuretics, except metolazone may be more effective in edema with renal impairment.a

Indapamide Dosage and Administration

General

Monitoring and BP Treatment Goals

-

Monitor BP regularly (i.e., monthly) during therapy and adjust dosage of the antihypertensive drug until BP controlled.1200

-

If unacceptable adverse effects occur, discontinue drug and initiate another antihypertensive agent from a different pharmacologic class.1200 1216

-

Assess patient's renal function and electrolytes 2–4 weeks after initiation of diuretic therapy.1200 (See Fluid and Electrolyte Imbalance under Cautions.)

-

If adequate BP response not achieved with a single antihypertensive agent, either increase dosage of single drug or add a second drug with demonstrated benefit and preferably a complementary mechanism of action (e.g., ACE inhibitor, angiotensin II receptor antagonist, calcium-channel blocker).1200 1216 Many patients will require at least 2 drugs from different pharmacologic classes to achieve BP goal; if goal BP still not achieved, add a third drug.1200 1216 1220

Administration

Administer orally as a single daily dose in the morning.21 83

Dosage

Individualize dosage according to individual requirements and response.600

For the management of fluid retention (e.g., edema) associated with heart failure, experts state that diuretics should be administered at a dosage sufficient to achieve optimal volume status and relieve congestion without inducing an excessively rapid reduction in intravascular volume, which could result in hypotension, renal dysfunction, or both.524

Adults

Hypertension

Usual Dosage

OralManufacturer recommends initial dosage of 1.25 mg once daily in the morning; if response is inadequate, dosage may be increased at 4-week intervals to 2.5 mg daily and subsequently to 5 mg daily.83

Some experts state that usual dosage range is 1.25–2.5 mg once daily.1200

Dosages >5 mg daily do not appear to result in further improvement in BP and increase the risk of hypokalemia.83 (See Hypokalemia under Cautions.)

If concomitant therapy with other antihypertensive agents is required, the usual dose of the other agent may need to be reduced initially by up to 50%; subsequent dosage adjustments should be based on BP response.44 83 Dosage reduction of both drugs may be required.39

Edema in Heart Failure

Oral

Initially, 2.5 mg once daily in the morning.83

If response is inadequate after 1 week, dosage may be increased to 5 mg daily given as a single dose in the morning.21 83

Dosages >5 mg daily do not appear to result in further improvement in heart failure and increase the risk of hypokalemia.83 24 29 39 83 (See Hypokalemia under Cautions.)

Edema (General)

Oral

Similar dosages to those employed for the management of edema associated with heart failure have been used in the management of edema from other causes†.29

Prescribing Limits

Adults

Oral

Dosages >5 mg daily do not appear to result in further improvement in heart failure or BP and are associated with increased risk of hypokalemia;24 29 39 83 clinical experience with such dosages is limited.24 29 39 83

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

No specific dosage recommendations.83 (See Hepatic Impairment under Cautions.)

Renal Impairment

No specific dosage recommendations.4 24 83 (See Renal Impairment under Cautions.)

Geriatric Patients

No specific dosage recommendations.83 (See Geriatric Use under Cautions.)

Cautions for Indapamide

Contraindications

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Hyponatremia

Severe hyponatremia (serum sodium concentration <120 mEq/L), accompanied by hypokalemia, occurs rarely.51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 Do not administer sodium chloride unless the hyponatremia is life threatening or actual sodium depletion is documented.21 If sodium chloride is administered, initially only correct to a state of mild hyponatremia; avoid early overcorrection to normonatremia or hypernatremia (risk of central pontine myelinolysis).52 55 60 62

Risk of hyponatremia appears to be dose related;51 52 53 54 55 56 61 83 risk is greater in patients receiving a daily dosage of 2.5 or 5 mg.83

Possible dilutional hyponatremia; occurs most commonly in patients with edema.21 51 54 Usually asymptomatic and managed by fluid intake restriction (e.g., 500 mL/day)21 and withdrawal of the diuretic.51 54

Hypokalemia

Hypokalemia occurs commonly.9 21 24 28 47 Increased risk of hypokalemia, especially with brisk diuresis; large dosages (i.e., ≥5 mg daily);21 24 29 39 40 83 inadequate oral electrolyte intake; in presence of severe cirrhosis, hyperaldosteronism, or potassium-losing renal diseases; or during concomitant use of corticosteroids or ACTH.21 24 83

Risk of hypochloremic alkalosis associated with hypokalemia, especially in patients with renal or liver disease; usually mild.21 Specific therapy generally not required.21

Supplemental potassium chloride (including potassium-containing salt substitutes) may be necessary to prevent or treat hypokalemia and/or metabolic alkalosis.21 28 44

Lithium

Generally, do not use with lithium salts.21 (See Specific Drugs under Interactions.)

Sensitivity Reactions

Dermatologic Reactions

Rash (e.g., erythematous, maculopapular, morbilliform), urticaria, pruritus, and vasculitis reported.21 63 In some cases, rash was accompanied by fever and/or dysuria.63 Rash generally resolves within 2 weeks after drug discontinuance, usually without specific therapy.63 64 May be treated with antihistamines.63

Erythema multiforme and epidermal necrolysis63 reported rarely.c

General Precautions

Fluid and Electrolyte Imbalance

Risk of electrolyte disturbances (e.g., hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypochloremic alkalosis, hypomagnesemia).21 1200 (See Hyponatremia and also Hypokalemia under Cautions.)

Periodic determinations of serum electrolyte concentrations (particularly potassium, sodium, chloride, and bicarbonate) should be performed and are especially important in patients at increased risk from hypokalemia (e.g., geriatric patients, those with cardiac arrhythmias, receiving concomitant cardiac glycosides, and/or with a history of ventricular arrhythmias),21 24 39 1200 and those with diabetes mellitus, vomiting, diarrhea, parenteral fluid therapy, or expectations of other electrolyte imbalance (e.g., heart failure, renal disease, cirrhosis, restricted sodium intake, advanced age).21 83 1200

Observe carefully for manifestations of fluid and electrolyte depletion (e.g., dryness of mouth, thirst, weakness, fatigue, lethargy, drowsiness, restlessness, muscle pains or cramps, muscular fatigue, hypotension, oliguria, tachycardia, arrhythmia, GI disturbance).21 83 1200 Measures to maintain normal serum concentrations should be instituted if necessary.21 83

Hyperuricemia

Risk of hyperuricemia, especially in patients with a history of gout, family predisposition to gout, or chronic renal failure.4 10 12 17 25 28 29 39 47 Usually asymptomatic and rarely leads to clinical gout.19 21 24 28 29 39

Generally avoid or use with caution in hypertensive patients with a history of gout unless patient is receiving uric acid lowering therapy.502 1200

Monitor serum uric acid concentrations periodically.83 Hyperuricemia and gout may be treated with a uricosuric agent.28 39

Endocrine Effects

Risk of increased blood glucose, hyperglycemia, glycosuria, and impaired glucose tolerance;15 21 24 28 precipitation of diabetes mellitus rarely reported in patients with a history of impaired glucose tolerance (latent diabetes).21

Monitor blood glucose concentrations periodically, especially in patients with known or suspected (e.g., marginally impaired glucose tolerance) diabetes mellitus.21

Hypercalcemia

May decrease calcium urinary excretion; slight intermittent serum calcium increases reported;83 clinically important changes in serum total or ionic calcium concentrations have not been reported.20 21 24

Use with caution in patients with hyperparathyroidism or thyroid disorders.21 Discontinue prior to performing parathyroid tests.21 83

Lupus Erythematosus

Possible exacerbation or activation of systemic lupus erythematosus.21 83

Sympathectomy

Antihypertensive effect may be enhanced after sympathectomy.21

Fetal/Neonatal Morbidity

Diuretics cross the placental barrier and appear in cord blood.83 Use with caution; possibility of fetal or neonatal jaundice, thrombocytopenia, and other adverse effects reported in adults.83

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Category B.83

Diuretics are considered second-line agents for control of chronic hypertension in pregnant women;142 if initiation of antihypertensive therapy is necessary during pregnancy, other antihypertensives (i.e., methyldopa, nifedipine, labetalol) are preferred.142 540

Diuretics are not recommended for prevention or management of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia.141 539 540

Lactation

Not known whether distributed into human milk.83 Manufacturer states to discontinue nursing or the drug;83 however, considered to be compatible with breast-feeding.141

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy not established.83

Geriatric Use

Use with caution in geriatric patients, especially females who are underweight; increased risk of dilutional hyponatremia.51 52 53 54 55 56 61 (See Hyponatremia under Cautions.)

Increased risk of hypokalemia; close monitoring recommended.21 24 39 (See Hypokalemia under Cautions.)

Hepatic Impairment

Use with caution in hepatic impairment or progressive liver disease (particularly with associated potassium deficiency); electrolyte and fluid imbalance may precipitate hepatic coma.21 83

Increased risk of hypochloremic alkalosis associated with hypokalemia.21

Renal Impairment

Use with caution in patients with severe renal disease; reduced plasma volume may exacerbate or precipitate azotemia.4 21 83

Increased risk of hypochloremic alkalosis associated with hypokalemia.21

Risk of hyperuricemia in patients with chronic renal failure.4 10 12 17 25 28 29 39 47

Diuretic effect declines with decreasing renal function.4 21 83

Evaluate renal function (e.g., BUN, Scr) periodically.21

Consider interruption or discontinuance if progressive renal impairment (rising nonprotein nitrogen, BUN, or Scr) occurs.21 83

Common Adverse Effects

Hypokalemia,9 21 24 28 47 headache,3 21 24 28 dizziness,3 21 24 28 29 fatigue,3 21 24 weakness,21 29 lethargy,21 tiredness,21 malaise,21 muscle cramps or spasm,3 21 24 29 numbness of the extremities,21 nervousness,21 24 tension, anxiety, irritability, agitation.21 83

Interactions for Indapamide

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Antihypertensive agents |

Additive hypotensive effect;21 44 83 possible potentiation of postural hypotension21 |

Usually used to therapeutic advantage21 83 If concomitant therapy with other antihypertensive agents is required, dose of the other agent may need to be reduced initially by up to 50%; subsequent dosage adjustments should be based on BP response;44 83 dosage reduction of both drugs may be required39 Monitor for possible postural hypotension21 |

|

Digitalis glycosides |

Possible electrolyte disturbances (e.g., hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia) may predispose to digitalis toxicity; possibly fatal cardiac arrhythmias21 |

Monitor electrolytes; correct hypokalemia21 |

|

Diuretics, potassium-sparing (e.g., amiloride, triamterene) |

Concomitant therapy not fully evaluated40 |

Safety and efficacy of concurrent use for the prevention of hypokalemia have not been fully determined40 |

|

Insulin |

Possible precipitation of diabetes mellitus21 and altered insulin requirements83 (see Endocrine Effects under Cautions) |

Monitor blood glucose concentrations periodically, especially in patients with known or suspected (e.g., marginally impaired glucose tolerance) diabetes mellitus21 |

|

Lithium |

Reduced renal clearance of lithium and increased risk of lithium toxicity21 23 24 |

Concomitant use generally contraindicated21 If concomitant therapy is necessary, monitor serum lithium concentrations and reduce lithium dosage by about 50%23 35 |

|

Potassium-depleting drugs (e.g., corticosteroids, corticotropin, amphotericin B) |

Additive hypokalemic effects21 |

Monitor electrolytes; correct hypokalemia83 |

|

Vasopressors (e.g., norepinephrine, phenylephrine) |

Possible decrease in arterial responsiveness to vasopressors21 24 27 39 |

Unlikely to be clinically important21 |

Indapamide Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Rapidly and completely absorbed following oral administration, with peak plasma concentration usually attained within 2–2.5 hours.16 20 21 24 39 83

Food

Food or antacids do not appear to affect absorption.20 24

Distribution

Extent

Lipophilic; widely distributed into most tissues.16 20 24

Not known whether indapamide crosses the placenta or is distributed into milk.21 40

Preferentially and reversibly distributes into erythrocytes;20 21 25 39 83 whole blood/plasma ratio is about 6 during peak concentration20 21 24 and about 3.5 eight hours after administration.21 83

Competitively and reversibly binds to carbonic anhydrase in erythrocytes, but does not appreciably inhibit the enzyme.24 39

Plasma Protein Binding

Approximately 71–79%.20 21 24 39 83

Elimination

Metabolism

Extensively metabolized in the liver, principally to glucuronide and sulfate conjugates.16 20 21 24 39

Elimination Route

Excreted in urine (70%) mainly as metabolites and in feces (16–23%), probably including biliary elimination.20 21 25 39 83

Half-life

Biphasic; terminal half-life is approximately 14–26 hours.16 20 21 24 39 83

Special Populations

Half-life is not prolonged in patients with impaired renal function.4 20 24

Not removed from circulation by hemodialysis.4

Stability

Storage

Oral

Tablets

Tight, light-resistant containers at 20–25°C; avoid excessive heat.600

Actions

-

A sulfonamide diuretic; 12 24 pharmacologically and structurally related to thiazide diuretics.6 8 12 14 18 21 24 25 26 38 39 42

-

Enhances excretion of sodium, chloride, and water by interfering with the transport of sodium ions across the renal tubular epithelium.12 20 24 25 26 39

-

Exact tubular mechanism(s) of action is not known;25 principal site of action appears to be the cortical diluting segment of the distal convoluted tubules of the nephron.20 21 25 26 39

-

Appears to indirectly increase potassium excretion by increasing the sodium load at the distal renal tubular site of sodium-potassium exchange.20 24

-

Increases proximal calcium reabsorption and does not inhibit distal calcium reabsorption in the renal tubules.20 21 24 25

-

Decreases free water clearance during hydration20 24 but not during dehydration.20

-

May increase plasma renin activity and urinary aldosterone secretion.2 24 27

-

Hypotensive activity in hypertensive patients;19 20 21 24 28 also augments the action of other hypotensive agents.21

-

Precise mechanism of hypotensive action has not been determined, but postulated that diuretics lower BP mainly by reducing plasma and extracellular fluid volume41 44 and by decreasing peripheral vascular resistance possibly secondary to sodium depletion43 and/or vascular autoregulatory feedback mechanisms;41 however, part of the hypotensive effect of indapamide may be caused by direct arteriolar dilation.5 6 21 24 25 27 39

-

Usually no effect on cardiac output20 21 or left ventricular function12 13 in hypertensive patients.21 24

Advice to Patients

-

Importance of informing patients of the signs and symptoms of electrolyte imbalance and instructing them to contact their clinician if dryness of mouth, thirst, weakness, lethargy, drowsiness, restlessness, oliguria, hypotension, tachycardia, GI disturbance, or muscle pains or cramps occur.21

-

Importance of informing patients with diabetes mellitus that blood glucose and urine glucose concentrations may increase.83

-

Advise hypertensive patients of importance of continuing lifestyle/behavioral modifications that include weight reduction (for those who are overweight or obese), dietary changes to include foods that are rich in potassium and calcium and moderately restricted in sodium (adoption of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH] eating plan), increased physical activity, smoking cessation, and moderation of alcohol intake.1200

-

Advise that lifestyle/behavioral modifications reduce BP, enhance antihypertensive drug efficacy, and decrease cardiovascular risk and remain an indispensable part of the management of hypertension.1200

-

Importance of informing clinicians of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs, as well as any concomitant illnesses.83

-

Importance of women informing clinicians if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.83

-

Importance of informing patients of other important precautionary information. (See Cautions.)

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

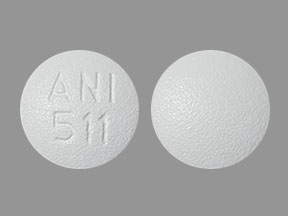

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Tablets, film-coated |

1.25 mg* |

Indapamide Tablets |

|

|

2.5 mg* |

Indapamide Tablets |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2022, Selected Revisions January 14, 2019. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

2. Noveck RJ, Quiroz A, Giles T et al. Hemodynamic effects of a new antihypertensive-diuretic, indapamide in healthy male volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1982; 31:257.

3. Passeron J, Pauly N, Desprat J. International multicentre study of indapamide in the treatment of essential arterial hypertension. Postgrad Med J. 1981; 57(Suppl. 2):57-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7033949?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2424762&blobtype=pdf

4. Acchiardo SR, Skoutakis VA. Clinical efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of indapamide in renal impairment. Am Heart J. 1983; 106:237-44. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6346847?dopt=AbstractPlus

5. Mironneau J, Gargouil Y. Action of indapamide on excitation-contraction coupling in vascular smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol. 1979; 57:57-67. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/477742?dopt=AbstractPlus

6. Mironneau J, Savineau J, Mironneau C. Compared effects of indapamide, hydrochlorothiazide, and chlorthalidone on electrical and mechanical actions in vascular smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol. 1981; 75:109-13. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7318900?dopt=AbstractPlus

7. Guidi G, Giuntoli F, Saba G et al. Clinical investigation on efficacy of indapamide as an antihypertensive agent. Curr Ther Res. 1982; 31:601-7.

8. Chalmers JP, Bune AJC, Graham JR et al. Comparison of indapamide with thiazide diuretics in patients with essential hypertension. Med J Aust. 1981; 2:100-1. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7300705?dopt=AbstractPlus

9. Wheeley MSG, Bolton JC, Campbell DB. Indapamide in hypertension: a study in general practice of new or previously poorly controlled patients. Pharmatherapeutica. 1982; 3:143-51. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7100225?dopt=AbstractPlus

10. Weidman P, Meier A, Mordasini R et al. Diuretics, indapamide and serum lipoproteins. Postgrad Med J. 1981; 57(Suppl. 2):73.

11. Haiat R, Lellouch A, Lanfranchi J et al. Continuous electrocardiographic recording (Holter method) during indapamide treatment: a study of 40 cases. Postgrad Med J. 1981; 57(Suppl. 2):68-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7322960?dopt=AbstractPlus

12. Horgan JH, O’Donovan A, Teo KK. Echocardiographic evaluation of left ventricular function in patients showing an antihypertensive and biochemical response to indapamide. Postgrad Med J. 1981; 57(Suppl. 2):64-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7033950?dopt=AbstractPlus

13. Dunn FG, Hillis WS, Tweddel A et al. Non-invasive cardiovascular assessment of indapamide in patients with essential hypertension. Postgrad Med J. 1981; 57(Suppl. 2):19-22. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7322955?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2424792&blobtype=pdf

14. Zacharis FJ. A comparative study of the efficacy of indapamide and bendrofluazide given in combination with atenolol. Postgrad Med J. 1981; 57(Suppl. 2):51-2. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7033947?dopt=AbstractPlus

15. Roux P, Courtois H. Blood sugar regulation during treatment with indapamide in hypertensive diabetics. Postgrad Med J. 1981; 57(Suppl. 2):70-2. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7322961?dopt=AbstractPlus

16. Grebow PE, Trectman JA, Barry EP et al. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of indapamide—a new antihypertensive drug. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1982; 22:295-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7106164?dopt=AbstractPlus

17. Van Hee W, Thomas J, Brems H. Indapamide in the treatment of essential arterial hypertension in the elderly. Postgrad Med J. 1981; 57(Suppl. 2):29-33. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7033944?dopt=AbstractPlus

18. James I, Griffith D, Davis J et al. Comparison of the antihypertensive effects of indapamide and cyclopenthiazide. Postgrad Med J. 1981; 57(Suppl. 2):39-41. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7322959?dopt=AbstractPlus

19. Morledge JH. Clinical efficacy and safety of indapamide in essential hypertension. Am Heart J. 1983; 106:229-32. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6346846?dopt=AbstractPlus

20. Caruso FS, Szabadi RR, Vukovich RA. Pharmacokinetics and clinical pharmacology of indapamide. Am Heart J. 1983; 106:212-20. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6869203?dopt=AbstractPlus

21. Rorer Pharmaceuticals. Lozol (indapamide) tablets prescribing information. Fort Washington, PA; 1990 Jul.

22. Kradjan WA, Koda-Kimble MA. Congestive heart failure. In: Katcher BS, Young LY, Koda-Kimble MA, eds. Applied therapeutics: the clinical use of drugs. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Applied Therapeutics, Inc.; 1983:176.

23. Coleman JH, Johnston JA. Affective disorders. In: Katcher BS, Young LY, Koda-Kimble MA, eds. Applied therapeutics: the clinical use of drugs. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Applied Therapeutics, Inc.; 1983:1035-6.

24. Chaffman M, Heel RC, Brogden TM et al. Indapamide, a review of its pharmacodynamic properties and therapeutic efficacy in hypertension. Drugs. 1984; 28:189-35. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6489195?dopt=AbstractPlus

25. Materson BJ. Insights into intrarenal sites and mechanisms of action of diuretic agents. Am Heart J. 1983; 106:188-208. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6869201?dopt=AbstractPlus

26. Pruss T, Wolf PS. Preclinical studies of indapamide, a new 2-methylindoline antihypertensive agent. Am Heart J. 1983; 106:208-11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6869202?dopt=AbstractPlus

27. Noveck RJ, McMahon FG, Quiros A et al. Extrarenal contributions to indapamide’s antihypertensive mechanism of action. Am Heart J. 1983; 106:221-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6869204?dopt=AbstractPlus

28. Beling S, Vukovich RA, Neiss ES et al. Long-term experience with indapamide. Am Heart J. 1983; 106:258-62. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6346848?dopt=AbstractPlus

29. Slotkoff L. Clinical efficacy and safety of indapamide in the treatment of edema. Am Heart J. 1983; 106:233-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6869205?dopt=AbstractPlus

30. US Food and Drug Administration. Limited usefulness of diuretics in pregnancy. FDA Drug Bull. 1977; 7:7.

31. Perez-Stable E, Caralis PV. Thiazide-induced disturbances in carbohydrate, lipid, and potassium metabolism. Am Heart J. 1983; 106:245-51. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6869206?dopt=AbstractPlus

32. Grimm RH, Leon AS, Hunninghake DB et al. Effects of thiazide diuretics on plasma lipids and lipoproteins in mildly hypertensive patients. Ann Intern Med. 1981; 94:7-11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7447225?dopt=AbstractPlus

33. Goldman AI, Steele BW, Schnaper HW et al. Serum lipoprotein levels during chlorthalidone therapy, a Veterans Administration—National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute cooperative study on antihypertensive therapy: mild hypertension. JAMA. 1980; 244:1691-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6997522?dopt=AbstractPlus

34. Helgeland A, Leren P, Foss OP et al. Serum glucose levels during long-term observation of treated and untreated men with mild hypertension. Am J Med. 1984; 76:802-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6720727?dopt=AbstractPlus

35. Lott RS. Lithium interactions. Drug Interact Newsl. 1983; 3:17-22.

36. Rowe JW, Tobin JD, Rosa RM et al. Effect of experimental potassium deficiency on glucose and insulin metabolism. Metabolism. 1980; 29:498-502. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6991855?dopt=AbstractPlus

37. Helderman JH, Elahi D, Anderson DK et al. Prevention of glucose intolerance of thiazide diuretics by maintenance of body potassium. Diabetes. 1983; 32:106-11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6337892?dopt=AbstractPlus

38. Windholz M, ed. The Merck index. 10th ed. Rahway, NJ: Merck & Co., Inc.: 1983.

39. Mroczek WJ. Indapamide: clinical pharmacology, therapeutic efficacy in hypertension, and adverse effects. Pharmacotherapy. 1983; 3:61-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6856486?dopt=AbstractPlus

40. Hansen KB (Revlon Health Care Group Ethical Products Division, Tarrytown, NY): Personal communication; 1984 Oct 1.

41. Freis ED. How diuretics lower blood pressure. Am Heart J. 1983; 106:185-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6869200?dopt=AbstractPlus

42. Mudge GH. Drugs affecting renal function and electrolyte metabolism. In: Gilman AG, Goodman L, Gilman A, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 6th ed. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company; 1980:899-903.

43. Blaschke TF, Melmon KL. Antihypertensive agents and the drug therapy of hypertension. In: Gilman AG, Goodman L, Gilman A, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 6th ed. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company; 1980:803-4.

44. Reviewers’ comments (personal observations); 1984 Oct.

45. The United States Pharmacopeial Convention, Inc. Indapamide tablets. Pharmacopeial Forum. 1989; 15:5475-7.

46. Scalabrino A, Galeone F, Giuntoli F et al. Clinical investigation on long-term effects of indapamide in patients with essential hypertension. Curr Ther Res. 1984; 35:17-22.

47. Weidman P, Bianchetti MG, Mordasini R. Effects of indapamide and various diuretics alone or combined with beta-blockers on serum lipoproteins. Curr Med Res Opin. 1983 (Suppl. 3); 8:123-34.

49. Kaplan NM. Initial treatment of adult patients with essential hypertension. Part II: alternating monotherapy is the preferred treatment. Pharmacotherapy. 1985; 5:195-200. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4034407?dopt=AbstractPlus

50. Bauer JH. Stepped-care approach to the treatment of hypertension: is it obsolete? (unpublished observations)

51. Ayus JC. Diuretic-induced hyponatremia. Arch Intern Med. 1986; 146:1295. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3718124?dopt=AbstractPlus

52. Ashouri OS. Severe diuretic-induced hyponatremia in the elderly: a series of eight patients. Arch Intern Med. 1986; 146:1355-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3718133?dopt=AbstractPlus

53. Sonnenblick M, Algur N, Rosin A. Thiazide-induced hyponatremia and vasopressin release. Ann Intern Med. 1989; 110:751. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2930114?dopt=AbstractPlus

54. Friedman E, Shadel M, Halkin H et al. Thiazide-induced hyponatremia: reproducibility by single dose rechallenge and an analysis of pathogenesis. Ann Intern Med. 1989; 110:24-30. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2491733?dopt=AbstractPlus

55. Sterns RH. Severe symptomatic hyponatremia: treatment and outcome. Ann Intern Med. 1987; 107:656-64. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3662278?dopt=AbstractPlus

56. Bain PG, Egner W, Walker PR. Thiazide-induced dilutional hyponatremia masquerading as subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet. 1986; 2:634. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2875352?dopt=AbstractPlus

57. Booker JA. Severe symptomatic hyponatremia in elderly outpatients: the role of thiazide therapy and stress. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1984; 32:108-13. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6693695?dopt=AbstractPlus

58. Johnson JE, Wright LF. Thiazide-induced hyponatremia. South Med J. 1983; 76:1363-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6635723?dopt=AbstractPlus

59. Kone B, Gimenez L, Watson AJ. Thiazide-induced hyponatremia. South Med J. 1986; 79:1456-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3775478?dopt=AbstractPlus

60. Mozes B, Pines A, Werner D et al. Thiazide-induced hyponatremia: an unusual neurologic course. South Med J. 1986; 79:629-31. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3704734?dopt=AbstractPlus

61. Oles KS, Denham JW. Hyponatremia induced by thiazide-like diuretics in the elderly. South Med J. 1984; 77:1314-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6484653?dopt=AbstractPlus

62. Ayus JC, Krothapalli RK, Arieff Al. Changing concepts in treatment of severe symptomatic hyponatremia: rapid correction and possible relation to central pontine myelinolysis. Am J Med. 1985; 78(6 Part 1):897-902. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4014266?dopt=AbstractPlus

63. Stricker BHC, Biriell C. Skin reactions and fever with indapamide. BMJ. 1987; 295:1313-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2961407?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1248382&blobtype=pdf

64. Kandela D, Guez D. Skin reactions and fever with indapamide. BMJ. 1988; 296:573. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2964890?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2545207&blobtype=pdf

67. Kaplan NM. Choice of initial therapy for hypertension. JAMA. 1996; 275:1577-80. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8622249?dopt=AbstractPlus

68. Psaty BM, Smith NL, Siscovich DS et al. Health outcomes associated with antihypertensive therapies used as first-line agents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 1997; 277:739-45. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9042847?dopt=AbstractPlus

69. Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Espeland MA et al. or the TONE Collaborative Research Group. Sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older persons: a randomized controlled trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly (TONE). JAMA. 1998; 279:839-46. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9515998?dopt=AbstractPlus

70. Anon. Consensus recommendations for the management of chronic heart failure. On behalf of the membership of the advisory council to improve outcomes nationwide in heart failure. Part II. Management of heart failure: approaches to the prevention of heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1999; 83:9-38A.

71. The Captopril-Digoxin Multicenter Research Group. Comparative effects of therapy with captopril and digoxin in patients with mild to moderate heart failure. JAMA. 1988; 259:539-44. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2447297?dopt=AbstractPlus

72. Richardson A, Bayliss J, Scriven AJ et al. Double-blind comparison of captopril alone against frusemide plus amiloride in mild heart failure. Lancet. 1987; 2:709-11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2888942?dopt=AbstractPlus

73. Sherman LG, Liang CS, Baumgardner S et al. Piretanide, a potent diuretic with potassium-sparing properties, for the treatment of congestive heart failure. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1986; 40:587-94. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3533372?dopt=AbstractPlus

74. Patterson JH, Adams KF Jr, Applefeld MM et al. Oral torsemide in patients with chronic congestive heart failure: effects on body weight, edema, and electrolyte excretion. Pharmacotherapy. 1994; 14:514-21. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7997385?dopt=AbstractPlus

75. Wilson JR, Reichek N, Dunkman WB et al. Effect of diuresis on the performance of the failing left ventricle in man. Am J Med. 1981;70:234-9.

76. Parker JO. The effects of oral ibopamine in patients with mild heart failure—a double blind placebo controlled comparison to furosemide. Int J Cardiol. 1993; 40:221-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8225657?dopt=AbstractPlus

77. Izzo JL, Levy D, Black HR. Importance of systolic blood pressure in older Americans. Hypertension. 2000; 35:1021-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10818056?dopt=AbstractPlus

78. Frohlich ED. Recognition of systolic hypertension for hypertension. Hypertension. 2000; 35:1019-20. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10818055?dopt=AbstractPlus

79. Bakris GL, Williams M, Dworkin L et al. Preserving renal function in adults with hypertension and diabetes: a consensus approach. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000; 36:646-61. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10977801?dopt=AbstractPlus

80. Associated Press (American Diabetes Association). Diabetics urged: drop blood pressure. Chicago, IL; 2000 Aug 29. Press Release from website. http://www.diabetes.org/newsroom/

81. Appel LJ. The verdict from ALLHAT—thiazide diuretics are the preferred initial therapy for hypertension. JAMA. 2002; 288:3039-42. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12479770?dopt=AbstractPlus

82. The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002; 288:2981-97. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12479763?dopt=AbstractPlus

83. Aventis Pharmaceuticals. Lozol (indapamide) tablets prescribing information. Bridgewater, NJ; 2002 Dec.

85. Neal B, MacMahon S, Chapman N. Effects of ACE inhibitors, calcium antagonists, and other blood-pressure-lowering drugs. Lancet. 2000; 356:1955-64. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11130523?dopt=AbstractPlus

86. Cushman WC, Ford CE, Cutler JA, et al. Success and predictors of blood pressure control in diverse North American settings: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2002; 4:393-404. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12461301?dopt=AbstractPlus

87. Black HR, Elliott WJ, Neaton JD et al. Baseline characteristics and elderly blood pressure control in the CONVINCE trial. Hypertension. 2001; 37:12-18. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11208750?dopt=AbstractPlus

88. Black HR, Elliott WJ, Grandits G, et al. Principal results of the Controlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular End Points (CONVINCE) trial. JAMA. 2003; 289:2073-2082. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12709465?dopt=AbstractPlus

89. Dahlof B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension Study (LIFE). Lancet. 2002; 359:995-1003. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11937178?dopt=AbstractPlus

90. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:145-153. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10639539?dopt=AbstractPlus

91. PROGRESS Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2001; 358:1033-41. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11589932?dopt=AbstractPlus

92. Wing LMH, Reid CM, Ryan P, et al, for Second Australian National Blood Pressure Study Group. A comparison of outcomes with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors and diuretics for hypertension in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003; 348:583-92. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12584366?dopt=AbstractPlus

93. American Diabetes Association. Treatment of hypertension in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003; 26(Suppl 1):S80-2.

94. Hunt SA, Baker DW, Chin MH, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic heart failure in the adult. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001; 38:2101-2113. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11738322?dopt=AbstractPlus

141. Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Yaffe SJ. Drugs in pregnancy and lactation: a reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011:255-8.

142. ACOG task force on hypertension in pregnancy: hypertension in pregnancy. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2013.

200. Douglas JG, Bakris GL, Epstein M et al. Management of high blood pressure in African Americans: Consensus statement of the Hypertension in African Americans Working Group of the International Society on Hypertension in Blacks. Arch Intern Med. 2003; 163:525-41. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12622600?dopt=AbstractPlus

218. National Kidney Foundation Guideline. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Kidney Disease Outcome Quality Initiative. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002; 39(Suppl 2):S1-246.

501. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014; 311:507-20. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24352797?dopt=AbstractPlus

502. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2013; 31:1281-357. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23817082?dopt=AbstractPlus

503. Go AS, Bauman MA, Coleman King SM et al. An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hypertension. 2014; 63:878-85. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24243703?dopt=AbstractPlus

504. Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014; 16:14-26. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24341872?dopt=AbstractPlus

505. Wright JT, Fine LJ, Lackland DT et al. Evidence supporting a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 150 mm Hg in patients aged 60 years or older: the minority view. Ann Intern Med. 2014; 160:499-503. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24424788?dopt=AbstractPlus

506. Mitka M. Groups spar over new hypertension guidelines. JAMA. 2014; 311:663-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24549531?dopt=AbstractPlus

507. Peterson ED, Gaziano JM, Greenland P. Recommendations for treating hypertension: what are the right goals and purposes?. JAMA. 2014; 311:474-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24352710?dopt=AbstractPlus

508. Bauchner H, Fontanarosa PB, Golub RM. Updated guidelines for management of high blood pressure: recommendations, review, and responsibility. JAMA. 2014; 311:477-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24352759?dopt=AbstractPlus

511. JATOS Study Group. Principal results of the Japanese trial to assess optimal systolic blood pressure in elderly hypertensive patients (JATOS). Hypertens Res. 2008; 31:2115-27. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19139601?dopt=AbstractPlus

515. Thomas G, Shishehbor M, Brill D et al. New hypertension guidelines: one size fits most?. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014; 81:178-88. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24591473?dopt=AbstractPlus

523. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2012; 126:e354-471.

524. WRITING COMMITTEE MEMBERS, Yancy CW, Jessup M et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013; 128:e240-327.

526. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR et al. Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014; :. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24788967?dopt=AbstractPlus

530. Myers MG, Tobe SW. A Canadian perspective on the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) hypertension guidelines. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014; 16:246-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24641124?dopt=AbstractPlus

535. Taler SJ, Agarwal R, Bakris GL et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for management of blood pressure in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013; 62:201-13. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23684145?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3929429&blobtype=pdf

536. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Blood Pressure Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the management of blood pressure in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012: 2: 337-414.

539. Churchill D, Beevers GD, Meher S et al. Diuretics for preventing pre-eclampsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007; :CD004451.

540. Magee LA, Pels A, Helewa M et al., for the Canadian Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy (HDP) Working Group. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2014; 4:105-45. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26104418?dopt=AbstractPlus

541. Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H et al. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur Heart J. 2012; 33:1635-701. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22555213?dopt=AbstractPlus

600. Mylan Pharmaceuticals. Indapamide tablets prescribing information. Morgantown, WV; 2010 Jan.

700. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B et al. 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update on New Pharmacological Therapy for Heart Failure: An Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2016; :.

713. Gupta D, Georgiopoulou VV, Kalogeropoulos AP et al. Dietary sodium intake in heart failure. Circulation. 2012; 126:479-85. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22825409?dopt=AbstractPlus

723. Hummel SL, Konerman MC. Dietary Sodium Restriction in Heart Failure: A Recommendation Worth its Salt?. JACC Heart Fail. 2016; 4:36-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26738950?dopt=AbstractPlus

724. Yancy CW. The Uncertainty of Sodium Restriction in Heart Failure: We Can Do Better Than This. JACC Heart Fail. 2016; 4:39-41. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26738951?dopt=AbstractPlus

1200. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018; 71:el13-e115. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29133356?dopt=AbstractPlus

1201. Bakris G, Sorrentino M. Redefining hypertension - assessing the new blood-pressure guidelines. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:497-499. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29341841?dopt=AbstractPlus

1202. Carey RM, Whelton PK, 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guideline Writing Committee. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: synopsis of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association hypertension guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018; 168:351-358. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29357392?dopt=AbstractPlus

1207. Burnier M, Oparil S, Narkiewicz K et al. New 2017 American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology guideline for hypertension in the adults: major paradigm shifts, but will they help to fight against the hypertension disease burden?. Blood Press. 2018; 27:62-65. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29447001?dopt=AbstractPlus

1209. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R et al. Pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in adults aged 60 years or older to higher versus lower blood pressure targets: a clinical practice guideline From the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017; 166:430-437. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28135725?dopt=AbstractPlus

1210. SPRINT Research Group, Wright JT, Williamson JD et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:2103-16. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26551272?dopt=AbstractPlus

1213. Reboussin DM, Allen NB, Griswold ME et al. Systematic review for the 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29146534?dopt=AbstractPlus

1216. Taler SJ. Initial Treatment of Hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:636-644. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29443671?dopt=AbstractPlus

1220. Cifu AS, Davis AM. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults. JAMA. 2017; 318:2132-2134. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29159416?dopt=AbstractPlus

1222. Bell KJL, Doust J, Glasziou P. Incremental benefits and harms of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association high blood pressure guideline. JAMA Intern Med. 2018; 178:755-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29710197?dopt=AbstractPlus

1223. LeFevre M. ACC/AHA hypertension guideline: What is new? What do we do?. Am Fam Physician. 2018; 97(6):372-3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29671534?dopt=AbstractPlus

1224. Brett AS. New hypertension guideline is released. From NEJM Journal Watch website. Accessed 2018 Jun 18. https://www.jwatch.org/na45778/2017/12/28/nejm-journal-watch-general-medicine-year-review-2017

1229. Ioannidis JPA. Diagnosis and treatment of hypertension in the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines and in the real world. JAMA. 2018; 319(2):115-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29242891?dopt=AbstractPlus

a. AHFS drug information 2017. McEvoy GK, ed. Thiazides general statement. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2017: .

c. AHFS drug information 2015. McEvoy GK, ed. Indapamide. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2015: .

Related/similar drugs

More about indapamide

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (29)

- Drug images

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: thiazide diuretics

- Breastfeeding

- En español