Aspirin (Monograph)

Brand names: Ascriptin, Aspergum, Bayer, Bufferin, Easprin,

... show all 11 brands

Drug class: Salicylates

- Antithrombotic Agents

- Platelet-aggregation Inhibitors

Aspirin (Systemic) is also contained as an ingredient in the following combinations:

Acetaminophen and Aspirin

Acetaminophen, Aspirin, and Caffeine

Oxycodone and Aspirin

Pentazocine Hydrochloride and Aspirin

Propoxyphene Hydrochloride, Aspirin, and Caffeine

Introduction

NSAIA; salicylate ester of acetic acid.a

Uses for Aspirin

Pain

Symptomatic relief of mild to moderate pain.a

Self-medication in children for the temporary relief of minor aches and pains and headache.841

Self-medication in adolescents and adults for the temporary relief of minor aches and pains associated with headache, common cold, toothache, muscular aches, backache, arthritis, menstrual cramps,836 and sore throat.837 840

Self-medication in fixed combination with acetaminophen and caffeine for the temporary relief of mild to moderate pain associated with migraine headache;701 702 703 also can be used for the treatment of severe migraine headache if previous attacks have responded to similar non-opiate analgesics or NSAIAs.701 702 703 778

Fever

Self-medication for reduction of fever associated with colds, sore throats, and teething.837 841 (See Contraindications and see Pediatric Use under Cautions.)

Inflammatory Diseases

Symptomatic treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, spondyloarthropathies, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).906 938 943 a

Rheumatic Fever

Symptomatic treatment of rheumatic fever† [off-label].a A drug of choice in patients with mild carditis (without cardiomegaly or CHF, with or without polyarthritis) or with polyarthritis only.h

Transient Ischemic Attacks and Ischemic Stroke

Reduction of the risk of recurrent TIAs or stroke or of death in patients with a history of TIAs or ischemic stroke (secondary prevention).646 682 842 906 938 1009

Also used in fixed combination with extended-release dipyridamole to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke, death from all vascular causes, or nonfatal MI in patients who have had TIAs or completed ischemic stroke caused by thrombosis.738 739 743 1009

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), the American Stroke Association (ASA), and AHA consider aspirin or the combination of aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole acceptable antiplatelet regimens for secondary prevention of noncardioembolic ischemic stroke and TIAs; other options include cilostazol or clopidogrel.990 1009 When selecting an appropriate antiplatelet regimen, consider factors such as the patient's individual risk for recurrent stroke, tolerance, and cost of the different agents.990

Oral anticoagulation (e.g., dabigatran, warfarin) rather than antiplatelet therapy is recommended in patients with a history of ischemic stroke or TIA and concurrent atrial fibrillation; however, in patients who cannot take or choose not to take oral anticoagulants (e.g., those with difficulty maintaining stable INRs, compliance issues, dietary restrictions, or cost limitations), dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel is recommended.1009

Also used for acute treatment of ischemic stroke in children† [off-label].1013

Coronary Artery Disease

Recommended by AHA and the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF) for reduction of the risk of vascular events (e.g., stroke, recurrent MI) in all patients with CAD, unless contraindicated.992

Recommended by American Diabetes Association (ADA) for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes mellitus and a history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).1116

ST-Segment-Elevation MI (STEMI)

Reduction of the risk of stroke, recurrent infarction, and death in patients with STEMI.527 579 842 992 1010

Use in conjunction with a P2Y12 platelet adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-receptor antagonist (e.g., clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor).527 992 993 994 1010

The addition of warfarin to antiplatelet therapy is recommended in patients with STEMI who have indications for anticoagulation (e.g., atrial fibrillation, left ventricular dysfunction, cerebral emboli, extensive wall-motion abnormality, mechanical heart valves).993 996 1007 1010

Primary Prevention of Ischemic Cardiac Events

Use of aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease remains controversial;1112 may reduce the risk of a first cardiac event (e.g., STEMI)† [off-label] in certain patient populations (primary prevention).1110 1117 1118 1119 Balance of risks and benefits is most favorable in patients at higher ASCVD risk who have a low risk of bleeding.1110 1111 1113 1114 1115

Some experts recommend reserving low-dose aspirin for primary prevention in adults 40–70 years of age who have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease without an increased risk of bleeding (e.g., history of previous GI bleed, peptic ulcer disease, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, chronic kidney disease, concomitant use of drugs that increase bleeding risk [e.g., NSAIAs, corticosteroids, direct oral anticoagulants, warfarin]).1110 1111

Consider totality of patient risk factors when determining risk for ASCVD, (e.g., strong family history of premature MI; inability to achieve lipid, BP, or blood glucose targets; substantial elevation in coronary artery calcium score) in conjunction with patient and clinician preferences.1110 1118 1119 High-risk patients also include adults 40–70 years of age without diabetes mellitus who have a 10-year ASCVD risk ≥20% and those with diabetes mellitus who have a 10-year ASCVD risk ≥10%.1111

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) states that the beneficial effects of aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease are modest and occur at daily dosages of ≤100 mg, with a potentially greater relative benefit for MI prevention in older adults.1117

ADA states may be considered for primary prevention in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus who are at high risk for cardiovascular events (i.e., familial history of premature ASCVD, smoking, hypertension, chronic kidney disease/albuminuria, elevated blood cholesterol or triglyceride concentrations) after evaluating risks versus benefits.1116

Not currently recommended for primary prevention in patients with a low risk of ASCVD.1110 Not routinely recommended for primary prevention in individuals <40 or >70 years of age.1110

Non-ST-Segment-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes (NSTE ACS)

Reduction of the risk of death and/or nonfatal MI in patients with NSTE ACS (unstable angina or non-ST-segment-elevation MI [NSTEMI]).581 613 614 615 616 617 618 619 620 621 682 684 728 736 906 938 1100

Dual-drug antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and a P2Y12-receptor antagonist (e.g., clopidogrel, ticagrelor) is considered part of the current standard of care for treatment and secondary prevention in patients with NSTE ACS.992 993 994 1010

Experts state that aspirin should be administered as soon as possible after presentation (and continued indefinitely) in all patients with NSTE ACS unless contraindicated; in addition, a P2Y12-receptor antagonist should be administered for up to 12 months.1100

Chronic Stable Angina

Reduction of the risk of MI and/or sudden death in patients with chronic stable angina.646 680 728 736 822 906 938

Experts recommend that aspirin therapy (75–162 mg daily) be continued indefinitely in patients with stable ischemic heart disease who do not have contraindications.1101

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and Revascularization Procedures

Reduction of cardiovascular risks (e.g., early ischemic complications, graft closure) in patients with ACS undergoing PCI (e.g., coronary angioplasty, coronary artery stent implantation)646 866 887 888 889 992 993 994 1010 or CABG.646 683 687 781 782

Pretreatment with aspirin prior to PCI recommended by ACCF, AHA, and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI).994 Adjunctive therapy with a P2Y12-receptor antagonist (e.g., clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor) also recommended in patients undergoing PCI with stent placement.994

Continue low-dose aspirin therapy indefinitely (as part of dual-drug antiplatelet therapy with a P2Y12-receptor antagonist for at least 12 months and possibly longer) as secondary prevention against cardiovascular events, including stent thrombosis, following PCI.993 994 1010 1019 1020

Embolism Associated with Atrial Fibrillation

Used as an alternative or adjunct to warfarin therapy for reduction of the incidence of thromboembolism in selected patients with chronic atrial fibrillation† [off-label].749 880 999 1007

ACCP, ASA, ACC, AHA, and other experts currently recommend that antithrombotic therapy be given to all patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (i.e., atrial fibrillation in the absence of rheumatic mitral stenosis, a prosthetic heart valve, or mitral valve repair) who are considered to be at increased risk of stroke, unless such therapy is contraindicated.989 990 999 1007 1017 1021 1022 1023

Choice of antithrombotic therapy is based on patient's risk for stroke and bleeding.999 1007 1021 1022 1023 In general, oral anticoagulant therapy (traditionally warfarin) is recommended in patients with high risk for stroke and acceptably low risk of bleeding, while aspirin or no antithrombotic therapy may be considered in patients at low risk of stroke.999 1007 1017 1021 1022 1023

In patients with atrial fibrillation at increased risk of stroke who cannot take or choose not to take oral anticoagulants for reasons other than concerns about major bleeding (e.g., those with difficulty maintaining stable INRs), combination therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin rather than aspirin alone is recommended.998 1007

Antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial flutter generally managed in the same manner as in patients with atrial fibrillation.999 1007

Peripheral Arterial Disease

Has been used for primary and secondary prophylaxis of cardiovascular events in patients with peripheral arterial disease, including those with intermittent claudication or carotid stenosis and those undergoing revascularization procedures (peripheral artery percutaneous transluminal angioplasty or peripheral arterial bypass graft surgery).1011

ACCP suggests the use of low-dose aspirin for primary prevention in patients with asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease.1011

For patients with symptomatic peripheral arterial disease or those undergoing revascularization procedures, single-drug antiplatelet therapy with aspirin or clopidogrel generally is recommended.1011

Valvular Heart Disease

Recommended by ACC and AHA for use in selected patients with mitral valve prolapse and atrial fibrillation, and also in symptomatic patients with mitral valve prolapse who experience TIAs.996

Prosthetic Heart Valves

Used for the prevention of thromboembolism in selected patients with prosthetic heart valves† [off-label].996 1008

ACCP and ACC/AHA suggest the use of low-dose aspirin for initial (i.e., first 3 months after valve insertion) and long-term antithrombotic therapy in patients with a bioprosthetic heart valve in the aortic position who are in sinus rhythm and have no other indications for warfarin.996 1008 Aspirin also may be considered after initial (3 months) warfarin therapy in patients with a bioprosthetic heart valve in the mitral position who are in sinus rhythm.1008

Addition of an antiplatelet agent such as low-dose aspirin to warfarin therapy recommended in all patients with mechanical heart valves who are at low risk of bleeding.996 1008 Combination therapy with aspirin and warfarin also recommended in patients with bioprosthetic heart valves who have additional risk factors for thrombosis (e.g., atrial fibrillation, previous thromboembolism, left ventricular dysfunction, hypercoagulable condition).996

May be added to therapy with a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or heparin (referring throughout this monograph to unfractionated heparin) in pregnant women with prosthetic heart valves† who are at high risk for thrombosis.1012

Thrombosis Associated with Fontan Procedure in Children

Has been used for prevention of thromboembolic complications following Fontan procedure† (definitive palliative surgical treatment for most congenital univentricular heart lesions) in children.1013

Thromboprophylaxis in Orthopedic Surgery

Has been used for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery (total-hip replacement, total-knee replacement, or hip-fracture surgery†).1003 Aspirin generally not considered the drug of choice for this use;1003 however, some evidence suggests some benefit over placebo or no antithrombotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery.953 954 1003

ACCP considers aspirin an acceptable option for pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery.1003

When selecting an appropriate thromboprophylaxis regimen, consider factors such as relative efficacy and bleeding risk in addition to other logistics and compliance issues.1003

Thromboprophylaxis in General Surgery

Has been used for thromboprophylaxis in patients undergoing general (e.g., abdominal) surgery who are at high risk of venous thromboembolism;1002 however, generally recommended as an alternative to LMWHs and low-dose heparin.1002

Pericarditis

Drug of choice for the management of pain associated with acute pericarditis† following MI.527

Kawasaki Disease

Treatment of Kawasaki disease; used in conjunction with immune globulin IV (IGIV).636 637 638 1013

Complications of Pregnancy

Has been used alone or in combination with other drugs (e.g., heparin, corticosteroids, immune globulin) for prevention of complications of pregnancy† (e.g., preeclampsia, pregnancy loss in women with a history of antiphospholipid syndrome and recurrent fetal loss).594 595 596 597 599 600 601 605 626 627 628 648 650 651 652 653 654 705 706 707 708 709 710 711 712 713 714 715 726 817 857 1012

Low-dose aspirin in combination with sub-Q heparin or an LMWH is recommended by ACCP in women with antiphospholipid antibody (APLA) syndrome† and a history of multiple (≥3) pregnancy losses.1012

Routine use of aspirin prophylaxis to reduce the incidence and severity of preeclampsia (even in patients at increased risk of preeclampsia) generally not recommended; 705 706 707 712 713 715 can consider prophylaxis in women with prior severe or early-onset preeclampsia, chronic hypertension, severe diabetes, or moderate to severe renal disease.815 816 817 In women at high risk for preeclampsia, ACCP recommends low-dose aspirin during pregnancy, starting from the second trimester.1012 (See Pregnancy under Cautions.)

Prevention of Cancer

Limited data (observational studies) suggest that aspirin or other NSAIAs may reduce the risk of various cancers† (e.g., colorectal, breast, gastric cancer);864 870 871 872 873 such results generally not confirmed in randomized controlled trials.864 874 875 876

Regular use (e.g., daily) associated with a reduction in the risk of recurrent colorectal adenomas and colorectal cancer† in some studies.789 790 791 792 793 794 795 796 797 798 799 800 801 802 803 804 805 806 807 808 809 810 811 812 813 814 815 Beneficial effects of NSAIAs in reducing colorectal cancer risk dissipate following discontinuance of such therapy.791 792 793 794 795 Preventive therapy with aspirin currently not recommended because aspirin does not completely eliminate adenomas; aspirin therapy should not be considered a replacement for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance.790 793 794 795 796 814

Aspirin Dosage and Administration

Administration

Administer orally; may administer rectally as suppositories in patients who cannot tolerate oral therapy.a

Do not use aspirin preparation if strong vinegar-like odor is present.a

Oral Administration

Usually administer orally with food or a full glass of water (240 mL).a 836 906

Film-coated, extended-release, or enteric-coated may be associated with less GI irritation and/or symptomatic GI disturbances than uncoated tablets.a

Do not use delayed-release or extended-release tablets if rapid response is required.a

Swallow delayed-release and extended-release tablets whole; do not crush or chew.a

Prepare oral solution by dissolving 2 tablets for solution (Alka-Seltzer) in 120 mL of water; ingest the entire solution to ensure adequate dosing.838 843 844

Do not chew aspirin preparations for ≥7 days following tonsillectomy or oral surgery;841 837 do not place preparations directly on tooth or gum surface (possible tissue injury from prolonged contact).a

Rectal Administration

Do not administer aspirin tablets rectally.a

Dosage

When used for pain, fever, or inflammatory diseases, attempt to titrate to the lowest effective dosage.a

When used in anti-inflammatory dosages, development of tinnitus can be used as a sign of elevated plasma salicylate concentrations (except in patients with high-frequency hearing impairment).a

Pediatric Patients

Dosage in children should be guided by body weight or body surface area.a 841

Do not use in children and teenagers with varicella or influenza, unless directed by a clinician.841 (See Contraindications under Cautions.)

Pain

Oral

Children 2–11 years of age: 1.5 g/m2 daily administered in 4–6 divided doses (maximum 2.5 g/m2 daily).a

Dose may be given every 4 hours as necessary (up to 5 times in 24 hours).841

|

Age |

Weight |

Oral Dose |

|---|---|---|

|

<3 years of age |

<14.5 kg |

Consult clinician |

|

3–<4 years |

14.5–16 kg |

160 mg |

|

4–<6 years |

16–20.5 kg |

240 mg |

|

6–<9 years |

20.5–30 kg |

320 mg |

|

9–<11 years |

30–35 kg |

320–400 mg |

|

11 years |

35–38 kg |

320–480 mg |

For self-medication in children ≥12 years of age, 325–650 mg every 4 hours (maximum 4 g daily) or 1 g every 6 hours as necessary.836 940

For self-medication in children ≥12 years of age, 454 mg (as chewing gum pieces) every 4 hours as necessary (maximum 3.632 g daily).837

For self-medication in children ≥12 years of age, 650 mg (as highly buffered effervescent solution [Alka-Seltzer Original]) every 4 hours (maximum 2.6 g daily); alternatively, 1 g (Alka-Seltzer Extra Strength) every 6 hours (maximum 3.5 g daily).843 844

Rectal

Children 2–11 years of age: 1.5 g/m2 daily administered in 4–6 divided doses (maximum 2.5 g/m2 daily).a

Children ≥12 years of age: 325–650 mg every 4 hours as necessary (maximum 4 g daily).a

Fever

Oral

Children 2–11 years of age: 1.5 g/m2 daily administered in 4–6 divided doses (maximum 2.5 g/m2 daily).a

Dose may be given every 4 hours as necessary (up to 5 times in 24 hours).841

|

Age |

Weight |

Oral Dose |

|---|---|---|

|

<3 years of age |

<14.5 kg |

Consult physician |

|

3–<4 years |

14.5–16 kg |

160 mg |

|

4–<6 years |

16–20.5 kg |

240 mg |

|

6–<9 years |

20.5–30 kg |

320 mg |

|

9–<11 years |

30–35 kg |

320–400 mg |

|

11 years |

35–38 kg |

320–480 mg |

Children ≥12 years of age: 325–650 mg every 4 hours as necessary (maximum 4 g daily).a

For self-medication in children ≥12 years of age, 454 mg (as chewing gum pieces) every 4 hours as necessary (maximum 3.632 g daily).837

Rectal

Children 2–11 years of age: 1.5 g/m2 daily administered in 4–6 divided doses (maximum 2.5 g/m2 daily).a

Children ≥12 years of age: 325–650 mg every 4 hours as necessary (maximum 4 g daily).a

Inflammatory Diseases

Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis

OralInitially, 90–130 mg/kg daily in divided doses.906 938 Increase dosage as necessary for anti-inflammatory efficacy; target plasma salicylate concentration is 150–300 mcg/mL.906 938 Plasma concentrations >200 mcg/mL associated with an increased incidence of toxicity.906 938

Rheumatic Fever†

Oral

Initially, 90–130 mg/kg daily given in divided doses every 4–6 hours for up to 1–2 weeks for maximal suppression of acute inflammation, followed by 60–70 mg/kg daily in divided doses for 1–6 weeks.a Adjust dosage based on response, tolerance, and plasma salicylate concentrations.a Gradually withdraw over 1–2 weeks.a

Various regimens suggested depending on severity of initial manifestations.a Consult published protocols for more information on specific dosages and schedules.a

Thrombosis

Acute Arterial Ischemic Stroke†

OralACCP recommends 1–5 mg/kg daily initially until cerebral arterial dissection and cardioembolic causes have been excluded; subsequently, continue same dosage for ≥2 years.1013

In children with acute arterial ischemic stroke secondary to non-Moyamoya vasculopathy, at least 3 months of therapy recommended; ongoing antithrombotic therapy should be guided by repeat cerebrovascular imaging.1013

Fontan Procedure†

Oral1–5 mg/kg daily recommended by ACCP; optimal duration of therapy unknown.1013

Prosthetic Heart Valves (Mechanical or Biological)†

OralACCP recommends that clinicians follow same recommendations as in adults.1013

Kawasaki Disease

Oral

Initially, 80–100 mg/kg daily given in 4 equally divided doses (in combination with IGIV) for up to 14 days; initiate within 10 days of onset of fever.636 637 638 639 640 1013 When fever subsides, decrease dosage to 1–5 mg/kg once daily.636 637 638 950 1013

Continue indefinitely in those with coronary artery abnormalities;638 950 1013 in the absence of such abnormalities, continue low-dose aspirin for 6–8 weeks.638 950 1013

Adults

Pain

Oral

For self-medication, 325–650 mg every 4 hours (maximum 4 g daily) or 0.5–1 g every 6 hours as necessary.836 940

For self-medication, 454 mg (as chewing gum pieces) every 4 hours as necessary (maximum 3.632 g daily).837

Adults <60 years of age for self-medication: 650 mg (as a highly buffered effervescent solution [Alka-Seltzer Lemon-Lime or Original]) every 4 hours (maximum 2.6 g daily); alternatively, 1 g (Alka-Seltzer Extra Strength) every 6 hours (maximum 3.5 g daily).838 843 844

Adults ≥60 years of age for self-medication: 650 mg (as a highly buffered effervescent solution [Alka-Seltzer Lemon-Lime or Original]) every 4 hours (maximum 1.3 g daily); alternatively, 1 g (Alka-Seltzer Extra Strength) every 6 hours (maximum 1.5 g daily).838 843 844

Rectal

325–650 mg every 4 hours as necessary (maximum 4 g daily).a

Pain Associated with Migraine Headache

OralFor self-medication, 500 mg (combined with acetaminophen 500 mg and caffeine 130 mg) as a single dose.701

Fever

Oral

325–650 mg every 4 hours as necessary (maximum 4 g daily).a

For self-medication, 454 mg (as chewing gum pieces) every 4 hours as necessary (maximum 3.632 g daily).837

Rectal

325–650 mg every 4 hours as necessary (maximum 4 g daily).a

Inflammatory Diseases

Rheumatoid Arthritis and Arthritis and Pleurisy of SLE

OralInitially, 3 g daily in divided doses.906 938 943 Increase dosage as necessary for anti-inflammatory efficacy; target plasma salicylate concentration is 150–300 mcg/mL.906 938 943 Plasma concentrations >200 mcg/mL associated with an increased incidence of toxicity.906 938 943

Osteoarthritis

OralUp to 3 g daily in divided doses.906 938

Spondyloarthropathies

OralUp to 4 g daily in divided doses.906 938

Rheumatic Fever†

Oral

Initially, 4.9–7.8 g daily in divided doses given for maximal suppression of acute inflammation.a Adjust dosage based on response, tolerance, and plasma salicylate concentrations.a

Various regimens suggested depending on severity of initial manifestations.a Consult published protocols for more information on specific dosages and schedules.a

Transient Ischemic Attacks and Acute Ischemic Stroke

Secondary Prevention

Oral50–325 mg daily;a 646 906 990 some data suggest lower dosages (75–81 mg daily) may have similar benefits and possibly less bleeding risk.907

In patients with noncardioembolic ischemic stroke or TIA, 75–100 mg daily (or 25 mg twice daily, in combination with extended-release dipyridamole 200 mg twice daily) recommended; continue long term.738 1009

Acute Treatment†

OralACCP recommends 160–325 mg daily, initiated ideally within 48 hours of stroke onset; may decrease dosage after 1–2 weeks to reduce bleeding risk. 1009 (See Transient Ischemic Attacks and Acute Ischemic Stroke: Secondary Prevention, under Dosage.) ACCP states that initiation of aspirin therapy should be delayed for 24 hours following administration of recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (r-tPA, e.g., alteplase).1009

Coronary Artery Disease and Myocardial Infarction

STEMI

Oral162–325 mg as soon as acute STEMI is suspected, continued indefinitely at a dosage of 81–325 mg daily.527 579 646 906 938 Some experts prefer use of a maintenance dosage of 81 mg daily because of a decreased risk of bleeding and lack of definitive evidence demonstrating that higher dosages confer greater benefit.527

Use in conjunction with a P2Y12-receptor antagonist (e.g., clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor).992 993 994 1010 If used with ticagrelor, do not exceed aspirin maintenance dosage of 100 mg daily; possible reduced efficacy of ticagrelor with such aspirin dosages.955

Primary Prevention† of STEMI

OralSome experts recommend 75–162 mg once daily in carefully selected patients.1110 1116 1118 1119 (See Primary Prevention of Ischemic Cardiac Events under Uses.)

Established Coronary Artery Disease

Oral75–100 mg daily recommended by ACCP; continue indefinitely.1010 Some data suggest lower dosages (75–81 mg daily) may have similar benefits and possibly less bleeding risk.907

NSTE ACS

OralACC and AHA recommend an initial dose of 162–325 mg as soon as possible after presentation, unless contraindicated.1100 Continue with maintenance dosage of 81–325 mg daily.1100

Use in conjunction with a P2Y12-receptor antagonist (e.g., clopidogrel, ticagrelor).991 992 993 994 1010 If used with ticagrelor, do not exceed aspirin maintenance dosage of 100 mg daily; possible reduced efficacy of ticagrelor with such aspirin dosages.955

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Surgery

OralPCI in patients already receiving aspirin: 81–325 mg initiated ≥2 hours, and preferably 24 hours, before the procedure in conjunction with a P2Y12-receptor antagonist.994

PCI in patients not already receiving long-term aspirin therapy: 325 mg daily (as non-enteric-coated formulation), initiated ≥2 hours, preferably 24 hours, prior to PCI in conjunction with a P2Y12-receptor antagonist.994

Maintenance therapy following PCI and stent placement (drug-eluting or bare-metal): 75–162 mg daily in combination with a P2Y12-receptor antagonist.992 994 1010 If used with ticagrelor, do not exceed aspirin maintenance dosage of 100 mg daily; possible reduced efficacy of ticagrelor with such aspirin dosages.955 Administer P2Y12-receptor antagonist for ≥12 months; continue aspirin indefinitely.994

CABG: Some manufacturers recommend 325 mg daily, initiated 6 hours after surgery.906 938 AHA and ACCF recommend 100–325 mg daily, initiated within 6 hours after CABG and continued for up to 1 year.992 For long-term therapy after 1 year, ACCP recommends aspirin 75–100 mg daily.1010

Embolism Associated with Atrial Fibrillation†

Oral

75–325 mg daily suggested for prevention of thromboembolism.1007

Manage atrial flutter in the same manner as atrial fibrillation.999 1007

Mitral Valve Prolapse†

Oral

75–325 mg daily.996

Peripheral Arterial Disease

Oral

Primary prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with asymptomatic disease: 75–100 mg daily.1011

Secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with symptomatic disease: 75–100 mg daily; continue long term.1011

Patients with refractory intermittent claudication: ACCP suggests the use of cilostazol in addition to aspirin therapy.1011

Peripheral Artery Bypass Graft Surgery

Oral

To reduce graft occlusion: 75–100 mg daily recommended by ACCP; initiate preoperatively and continue long term.1011

ACCP suggests addition of clopidogrel 75 mg daily to aspirin therapy in patients undergoing below-the-knee prosthetic graft bypass surgery.1011

Prosthetic Heart Valves

Mechanical Prosthetic Heart Valves†

OralAspirin 50–100 mg daily in addition to warfarin therapy recommended in all patients with a mechanical heart valve who have a low risk of bleeding.996 1008

Aspirin 75–325 mg once daily as monotherapy recommended as an alternative to warfarin in patients who are unable to take warfarin.996

Bioprosthetic Heart Valves†

OralPatients with bioprosthetic valves in the aortic position: 50–100 mg daily suggested by ACCP for initial (i.e., first 3 months after valve insertion) and long-term therapy.1008

Patients with bioprosthetic heart valves in the mitral position: 50–100 mg daily may be used for long-term antithrombotic therapy after initial 3-month treatment with warfarin.1008

Combination aspirin (75–100 mg daily) and warfarin therapy recommended by ACC/AHA for patients with bioprosthetic heart valves and additional risk factors for thromboembolism.996

Aspirin 75–325 mg once daily also recommended as an alternative to warfarin therapy in any patient who is unable to take warfarin.996

Complications of Pregnancy†

Oral

Antiphospholipid syndrome† and a history of multiple (≥ 3) pregnancy losses: Antepartum prophylaxis with aspirin (75–100 mg daily) in combination with sub-Q heparin or an LMWH recommended by ACCP.1012

Patients at risk for preeclampsia: ACCP recommends low-dose aspirin during pregnancy (starting from the second trimester).1012

Prescribing Limits

Pediatric Patients

Pain

Oral

Children 2–11 years of age: Maximum 2.5 g/m2 daily.a

Children ≥12 years of age: Maximum 4 g daily.836 Maximum 2.6 g as highly buffered effervescent solution (Alka-Seltzer Original) or 3.5 g (Alka-Seltzer Extra Strength) in 24 hours.843 844

For self-medication, do not exceed recommended daily dosage.841 Treatment duration for self-medication for pain: ≤ 5 days.841 (See Advice to Patients.) Treatment duration for self-medication of sore throat pain using chewing gum: ≤2 days.837

Rectal

Children 2–11 years of age: Maximum 2.5 g/m2 daily.a

Children ≥12 years of age: Maximum 4 g daily.a

Fever

Oral

Children 2–11 years of age: Maximum 2.5 g/m2 daily.a

Children ≥12 years of age: Maximum 4 g daily.836

For self-medication, do not exceed recommended daily dosage.841 Treatment duration for self-medication: <3 days.841 (See Advice to Patients.)

Rectal

Children 2–11 years of age: Maximum 2.5 g/m2 daily.a

Children ≥12 years of age: Maximum 4 g daily.a

Adults

Pain

Oral

Maximum 4 g daily.a Treatment duration for self-medication for pain: ≤10 days.841 Aspirin chewing gum should not be used for self-medication of sore throat pain for longer than 2 days.837 (See Advice to Patients.)

Adults <60 years of age taking highly buffered effervescent solutions: Maximum 2.6 g (Alka-SeltzerLemon-lime or Original) or 3.5 g (Alka-Seltzer Extra Strength) in 24 hours.838 843 844

Adults ≥60 years of age taking highly buffered effervescent solutions: Maximum 1.3 g (Alka-SeltzerLemon-lime or Original) or 1.5 g (Alka-Seltzer Extra Strength) in 24 hours.838 843 844

Rectal

Maximum 4 g daily.a

Pain Associated with Migraine Headache

OralFor self-medication, maximum 500 mg (in combination with acetaminophen 500 mg and caffeine 130 mg) in 24 hours.701

Fever

Oral or Rectal

Maximum 4 g daily.a

Special Populations

Geriatric Patients

Highly buffered effervescent solution: Maximum 1.3 g (Alka-SeltzerLemon-Lime or Original) or 1.5 g (Alka-Seltzer Extra Strength) in 24 hours.838 843 844

Cautions for Aspirin

Contraindications

-

Known hypersensitivity to aspirin or any ingredient in the formulation.906 938

-

History of asthma, urticaria, or other sensitivity reaction precipitated by other NSAIAs.906 938

-

Syndrome of asthma, rhinitis, and nasal polyps.938

-

Children or adolescents with viral infections (with or without fever) because of the possibility that the infection may be one associated with an increased risk of Reye’s syndrome.906 938 (See Pediatric Use under Cautions.)

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Alcohol

Long-term heavy alcohol use (≥3 alcoholic beverages daily) associated with an increased risk of aspirin-induced bleeding.906 938 941 (See Advice to Patients.)

Hematologic Effects

Inhibits platelet aggregation and may prolong bleeding time.906 938 These effects may be particularly important in patients with inherited (e.g., hemophilia) or acquired (e.g., liver disease, vitamin K deficiency) bleeding disorders.906 938

Because of the increased risk of bleeding, avoid aspirin-containing chewing gum tablets or gargles for ≥1 week after tonsillectomy or oral surgery.h

GI Effects

Serious GI toxicity (e.g., bleeding, ulceration, perforation) can occur with or without warning symptoms.938 Increased risk in those with a history of GI bleeding or ulceration, geriatric patients, and those receiving an anticoagulant or corticosteroid, receiving excessive dosages or prolonged therapy, taking multiple NSAIAs concomitantly, or consuming ≥3 alcohol-containing beverages daily.941 1035

Avoid in patients with active peptic ulcer disease; can cause gastric mucosal irritation and bleeding.906 938

Despite current warnings on OTC product labels, serious bleeding events continue to occur in patients receiving aspirin in fixed combination with antacids for self-medication.1035 FDA is evaluating whether additional actions are needed to address this safety concern.1035

Thrombosis Associated with Drug-eluting Stents

Stent thrombosis with potentially fatal sequelae, particularly with drug-eluting stents (DES),886 890 891 associated with premature discontinuance (<12 months) of dual-drug therapy with a thienopyridine derivative and aspirin.886 890 891 892 893 894 895 896 897 898 899 900 (See Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and Revascularization Procedures under Uses.)

At least 12 months of dual-drug antiplatelet therapy is recommended in patients with any type of coronary artery stent (bare-metal or drug-eluting).993 994 1010 Preliminary evidence from a randomized controlled study suggests that an even longer duration (up to 30 months) of dual-drug antiplatelet therapy may be beneficial in reducing stent thrombosis and other cardiovascular events in patients with a drug-eluting stent; however, such prolonged therapy was associated with increased bleeding and an unexpected finding of increased all-cause mortality.1019 1020 FDA is continuing to evaluate these findings and will communicate final conclusions and recommendations once the analysis is complete.1019

For non-elective procedures that mandate premature discontinuance of thienopyridine-derivative therapy, continue aspirin therapy if at all possible.886 Restart thienopyridine therapy as soon as possible after the procedure.886 (See Advice to Patients.)

Sensitivity Reactions

Anaphylactoid reactions, severe urticaria, angioedema, or bronchospasm reported.836 906 938 h Immediate medical intervention and discontinuance for anaphylaxis.836

Potentially fatal or life-threatening syndrome of multi-organ hypersensitivity (i.e., drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms [DRESS]) reported in patients receiving NSAIAs.1202 Clinical presentation is variable, but typically includes eosinophilia, fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, and/or facial swelling, possibly associated with other organ system involvement (e.g., hepatitis, nephritis, hematologic abnormalities, myocarditis, myositis).1202 Symptoms may resemble those of acute viral infection.1202 Early manifestations of hypersensitivity (e.g., fever, lymphadenopathy) may be present in the absence of rash.1202 If signs or symptoms of DRESS develop, discontinue the drug and immediately evaluate the patient.1202

Contraindicated in patients with syndrome of asthma, rhinitis, and nasal polyps;906 938 caution in patients with asthma.938

General Precautions

Sodium Content

Avoid highly buffered aspirin preparations in patients with CHF, renal failure, or other conditions in which high sodium content would be harmful.906 938

Individuals with Phenylketonuria

Some preparations contain aspartame (NutraSweet), which is metabolized in the GI tract to phenylalanine.a 838

Use of Fixed Combinations

When aspirin is used in fixed combination with other agents, consider the cautions, precautions, and contraindications associated with the other agent(s).a

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Use of NSAIAs during pregnancy at about ≥30 weeks’ gestation can cause premature closure of the fetal ductus arteriosus; use at about ≥20 weeks’ gestation associated with fetal renal dysfunction resulting in oligohydramnios and, in some cases, neonatal renal impairment.1200 1202

Effects of NSAIAs on the human fetus during third trimester of pregnancy include prenatal constriction of the ductus arteriosus, tricuspid incompetence, and pulmonary hypertension; nonclosure of the ductus arteriosus during the postnatal period (which may be resistant to medical management); and myocardial degenerative changes, platelet dysfunction with resultant bleeding, intracranial bleeding, renal dysfunction or renal failure, renal injury or dysgenesis potentially resulting in prolonged or permanent renal failure, oligohydramnios, GI bleeding or perforation, and increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis.1202

Avoid use of NSAIAs in pregnant women at about ≥30 weeks’ gestation; if use required between about 20 and 30 weeks’ gestation, use lowest effective dosage and shortest possible duration of treatment, and consider monitoring amniotic fluid volume via ultrasound examination if treatment duration >48 hours; if oligohydramnios occurs, discontinue drug and follow up according to clinical practice.1200 1202 However, FDA states that these recommendations do not apply to low-dose aspirin therapy; low (e.g., 81-mg) doses of aspirin may be used under the direction of a clinician at any time during pregnancy for the treatment of certain pregnancy-related conditions.1200 (See Advice to Patients.)

Fetal renal dysfunction resulting in oligohydramnios and, in some cases, neonatal renal impairment observed, on average, following days to weeks of maternal NSAIA use; infrequently, oligohydramnios observed as early as 48 hours after initiation of NSAIAs.1200 1202 Oligohydramnios is often, but not always, reversible (generally within 3–6 days) following NSAIA discontinuance.1200 1202 Complications of prolonged oligohydramnios may include limb contracture and delayed lung maturation.1200 1202 In limited number of cases, neonatal renal dysfunction (sometimes irreversible) occurred without oligohydramnios.1200 1202 Some neonates have required invasive procedures (e.g., exchange transfusion, dialysis).1200 1202 Deaths associated with neonatal renal failure also reported.1200 Limitations of available data (lack of control group; limited information regarding dosage, duration, and timing of drug exposure; concomitant use of other drugs) preclude a reliable estimate of the risk of adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes with maternal NSAIA use.1202 Available data on neonatal outcomes generally involved preterm infants; extent to which risks can be generalized to full-term infants is uncertain.1202

Animal data indicate important roles for prostaglandins in kidney development and endometrial vascular permeability, blastocyst implantation, and decidualization.1202 In animal studies, inhibitors of prostaglandin synthesis increased pre- and post-implantation losses; also impaired kidney development at clinically relevant doses.1202

Maternal and fetal hemorrhagic complications observed with maternal ingestion of large doses (e.g., 12–15 g daily) of aspirin594 595 597 611 612 generally have not been observed in studies in which low doses (60–150 mg daily) of the drug were used for prevention of complications of pregnancy†.594 595 596 597 598 599 600 601 605 626 627 629 630 631 632

Lactation

Distributed into milk; use not recommended.906 938 High doses may result in adverse effects (rash, platelet abnormalities, bleeding) in nursing infants.906 938

Pediatric Use

Dosing recommendations for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis based on well controlled clinical studies.906 938 High dosages that result in plasma concentrations >200 mcg/mL associated with an increased incidence of toxicity.906 938

Use in children with varicella infection or influenza-like illnesses reportedly is associated with an increased risk of developing Reye’s syndrome.166 167 168 169 468 538 549 638 US Surgeon General, AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases, FDA, and other authorities advise that salicylates not be used in children and teenagers with varicella or influenza, unless directed by a clinician.466 467 554 638 Generally avoid salicylates in children and teenagers with suspected varicella or influenza and during presumed outbreaks of influenza, since accurate diagnosis of these diseases may be impossible during the prodromal period;466 use of salicylates in the management of viral infections in children or adolescents is contraindicated, since the infection may be one associated with an increased risk of Reye’s syndrome.646 906

Use with caution in pediatric patients who are dehydrated (increased susceptibility to salicylate intoxication).h

Safety and efficacy of aspirin in fixed combination with extended-release dipyridamole not established.738

Risk of overdosage and toxicity (including death) in children <2 years of age receiving preparations containing antihistamines, cough suppressants, expectorants, and nasal decongestants alone or in combination for relief of symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection.937 939 Limited evidence of efficacy for these preparations in this age group; appropriate dosages not established.937 Use such preparations in children <2 years of age with caution and only as directed by clinician.937 939 Clinicians should ask caregivers about use of OTC cough/cold preparations to avoid overdosage.937

Hepatic Impairment

Avoid in patients with severe hepatic impairment.906 938

Renal Impairment

Avoid in patients with GFR <10 mL/minute.906 938

Common Adverse Effects

Minor upper GI symptoms (dyspepsia).938

Drug Interactions

Protein-bound Drugs

Potential for salicylate to be displaced from binding sites by, or to displace from binding sites, other protein-bound drugs.906 h Aspirin acetylates serum albumin, which may alter binding of other drugs to the protein.a

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

ACE inhibitors |

Reduced BP response to ACE inhibitors938 Possible attenuation of hemodynamic actions of ACE inhibitors in patients with CHFh |

Monitor BP938 |

|

Acidifying agents |

Drugs that decrease urine pH may decrease salicylate excretionh |

|

|

Alcohol |

||

|

Alkalinizing agents |

Drugs that increase urine pH may increase salicylate excretionh |

Monitor plasma salicylate concentrations in patients receiving high-dose aspirin therapy if antacids are initiated or discontinuedh |

|

Anticoagulants (warfarin, heparin) |

Increased risk of bleeding906 938 May displace warfarin from protein-binding sites, leading to prolongation of PT and bleeding time906 938 |

Use with cautionh |

|

Anticonvulsants |

May displace phenytoin from binding sites; possible decrease in total plasma phenytoin concentrations, with increased free fraction906 938 May displace valproic acid from binding sites; possible increase in free plasma valproic acid concentrations;906 938 h possible increased risk of bleedingh |

Monitor patients receiving aspirin with valproic acidh |

|

Antidiabetic drugs (sulfonylureas) |

Monitor closelyh |

|

|

β-adrenergic blocking agents |

Reduced BP response to β-adrenergic blocking agents 906 938 Potential for salt and fluid retention906 |

Monitor BP938 |

|

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (acetazolamide) |

Increased risk of salicylate toxicityh Increased plasma acetazolamide concentrations; increased risk of acetazolamide toxicity906 938 |

Avoid concomitant use in patients receiving high-dose aspirinh |

|

Corticosteroids |

Decreased plasma salicylate concentrationsh |

Monitor for adverse effects of either drugh |

|

Diuretics |

Possible reduced natriuretic effect938 |

|

|

Methotrexate |

Increased plasma methotrexate concentrationsh Inhibition of renal clearance of methotrexate leading to bone marrow toxicity, especially in geriatric patients or patients with renal impairment906 |

Monitor for methotrexate toxicityh |

|

NSAIAs |

Increased risk of bleeding, GI ulceration, decreased renal function, or other complications861 906 946 947 948 No consistent evidence that low-dose aspirin mitigates increased risk of serious cardiovascular events associated with NSAIAs861 948 Pharmacokinetic interactions with many NSAIAsh Antagonism (ibuprofen, naproxen) of the irreversible platelet-aggregation inhibitory effect of aspirin; may limit the cardioprotective effects of aspirin788 858 859 860 Minimal risk of attenuating effects of low-dose aspirin with occasional use of ibuprofen858 Not known whether ketoprofen interferes with the antiplatelet effect of aspirin858 859 Decreased peak plasma concentration and AUC of diclofenac;946 947 limited data indicate that diclofenac does not inhibit antiplatelet effect of aspirin788 |

Concomitant use not recommended906 938 946 947 948 Pharmacokinetic interactions unlikely to be clinically importanth Immediate-release aspirin: Administer a single dose of ibuprofen 400 mg for self-medication≥8 hours before or ≥30 minutes after administration of aspirin858 859 Enteric-coated low-dose aspirin: No recommendations regarding timing of administration with single dose of ibuprofen858 859 Consider use of alternative analgesics that do not interfere with antiplatelet effect of low-dose aspirin (e.g., acetaminophen, opiates) for patients at high risk of cardiovascular events858 859 Concomitant use with prescription NSAIAs not recommended because of potential for increased adverse effects861 |

|

Pyrazinamide |

Possible prevention or reduction of hyperuricemia associated with pyrazinamideh |

|

|

Tetracycline |

Decreased oral absorption of tetracyclines when administered with aspirin preparations containing divalent or trivalent cations (Bufferin)h |

Administer preparations containing divalent or trivalent cations (Bufferin) 1 hr before or after tetracyclineh |

|

Thrombolytic agents |

Additive reduction in mortality reported in patients with AMI receiving aspirin in low dosages and thrombolytic agents (streptokinase, alteplase)579 580 581 582 583 584 585 586 587 588 589 590 |

Used for therapeutic effect579 580 581 582 583 584 585 586 587 588 589 590 |

|

Uricosuric agents (probenecid, sulfinpyrazone) |

||

|

Varicella virus vaccine live |

Theoretical possibility of Reye’s syndrome638 |

Manufacturer of varicella virus vaccine live recommends that individuals who receive the vaccine avoid use of salicylates for 6 weeks following vaccination756 For children who are receiving long-term salicylate therapy, AAP suggests weighing theoretical risks of vaccination against known risks of wild-type virus;638 ACIP states that children who have rheumatoid arthritis or other conditions requiring therapeutic salicylate therapy probably should receive varicella virus vaccine live in conjunction with subsequent close monitoring757 |

Aspirin Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Well absorbed following oral administration.906 h Rapidly metabolized to salicylic acid; plasma aspirin concentrations are undetectable 1–2 hours after administration.906 Peak plasma salicylic acid concentrations attained within 1–2 hours following administration of uncoated tablets.906

Slowly and variably absorbed following rectal administration.h

Onset

Single oral doses of rapidly absorbed preparations: 30 minutes for analgesic and antipyretic effects.h

Rectal suppositories: 1–2 hours for antipyretic effects.h

Continuous oral therapy: 1–4 days for anti-inflammatory effect.h

Food

Food decreases rate but not extent of absorption; peak plasma concentrations of aspirin and salicylate may be decreased.h

Plasma Concentrations

Plasma salicylate concentrations of 30–100 mcg/mL produce analgesia and antipyresis; the concentration required for anti-inflammatory effect is 150–300 mcg/mL; toxicity noted at 300–350 mcg/mL.h

Steady-state plasma salicylate concentrations increase more than proportionally with increasing doses as a result of capacity-limiting processes.h

Special Populations

During the febrile phase of Kawasaki disease, oral absorption may be impaired or highly variable.h

Distribution

Extent

Widely distributed; aspirin and salicylate distribute into synovial fluid.906 a h Crosses placenta and distributed into milk.906

Plasma Protein Binding

Aspirin: 33%.a

Salicylate: 90–95% bound at plasma salicylate concentrations <100 mcg/mL; 70–85% bound at concentrations of 100–400 mcg/mL; 25–60% bound at concentrations >400 mcg/mL.906 h

Elimination

Metabolism

Partially hydrolyzed to salicylate by esterases in the GI mucosa.a Unhydrolyzed aspirin subsequently undergoes hydrolysis by esterases mainly in the liver but also in plasma, erythrocytes, and synovial fluid.a

Salicylate is metabolized in the liver by the microsomal enzyme system.h

Elimination Route

Excreted in urine via glomerular filtration and renal tubular reabsorption as salicylate and its metabolites.h Urinary excretion of salicylate is pH dependent; as urine pH increases from 5 to 8, urinary excretion of salicylate is greatly increased.h

Half-life

Aspirin: 15–20 minutes.a

Half-life of salicylate increases with increasing plasma salicylate concentrations.906 h

Salicylate: 2–3 hours when aspirin administered in low doses (325 mg).h

Salicylate: 15–30 hours when aspirin administered in higher dosages.h

Special Populations

Salicylate and its metabolites readily removed by hemodialysis and, to a lesser extent, by peritoneal dialysis.h

Stability

Storage

Oral

Capsules

Aspirin in fixed-combination with extended-release dipyridamole: 25°C (may be exposed to 15–30°C).738 Protect from excessive moisture.738

Gum

15–25°C; protect from excessive moisture.837

Tablets

Room temperature (Bayer products, excluding Alka-Seltzer products);839 840 841 842 906 avoid high humidity and excessive heat (40°C).840

15–30°C (Easprin).943

20–25°C (Anacin Extra Strength); protect from moisture.836

Protect from excessive heat (Alka-Seltzer products).838 843 844

Rectal

Suppositories

2–15°C.a

Actions

-

Inhibits COX-1 and COX-2 activity.1016

-

Pharmacologic actions similar to those of prototypical NSAIAs; exhibits anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic activity.938

-

Irreversibly acetylates and inactivates COX-1 in platelets.1016

-

The existence of 2 COX isoenzymes with different aspirin sensitivities and extremely different recovery rates of their COX activity following inactivation by aspirin at least partially explains the different dosage requirements and durations of aspirin effects on platelet function versus the drug’s analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects.1016

-

Effects on urinary excretion of uric acid are dose related; large dosages (e.g., 1.3 g 4 times daily) enhance urinary excretion and decrease serum concentrations of uric acid , intermediate dosages (e.g., 650 mg to 1 g 3 times daily) usually do not alter uric acid excretion, and low dosages (e.g., <325 mg 3 times daily) inhibit excretion and may increase serum uric acid concentrations.h

Advice to Patients

-

When used for self-medication, importance of reading the product labeling.836 841 837 838 843 844 940

-

When used for self-medication, importance of asking clinician whether to use aspirin or another analgesic if alcohol consumption is ≥3 alcohol-containing drinks per day.836 837 838 841 843 844 940

-

Importance of informing patients about risk of bleeding associated with chronic, heavy alcohol use while taking aspirin.906 941

-

When used for self-medication in children, importance of basing the dose on the child’s weight or body surface area.841

-

In patients with drug-eluting stents (DES) receiving aspirin in combination with clopidogrel or ticlopidine, importance of not discontinuing antiplatelet therapy without consulting cardiologist, even if instructed to do so by other health-care professional (e.g., dentist).886

-

Importance of not using aspirin for chicken pox or flu symptoms in children or adolescents without consulting a clinician.836 837 838 841 843 844 940

-

Patients receiving anticoagulants and those with asthma, gout, diabetes, arthritis, peptic ulcers, bleeding problems, or stomach problems that persist or recur should consult a clinician before using aspirin for self-medication.836 837 838 841 843 844 940

-

Discontinue and consult clinician if pain or fever persists or progresses, new symptoms occur, redness or swelling is present in a painful area, or ringing in the ears or loss of hearing occurs.836 837 838 841 843 844 940

-

Risk of GI bleeding or ulceration, particularly with prolonged therapy,906 938 941 and concomitant therapy with another NSAIA.941

-

Risk of anaphylactoid and other sensitivity reactions.938

-

Importance of notifying clinician if signs and symptoms of GI ulceration or bleeding or rash develop.938

-

Importance of seeking immediate medical attention if an anaphylactic reaction occurs.938

-

Importance of women informing clinicians if they are or plan to become pregnant or to breast-feed.938

-

Importance of avoiding NSAIA use beginning at 20 weeks’ gestation unless otherwise advised by a clinician; importance of avoiding NSAIAs beginning at 30 weeks’ gestation because of risk of premature closure of the fetal ductus arteriosus; monitoring for oligohydramnios may be necessary if NSAIA therapy required for >48 hours’ duration between about 20 and 30 weeks’ gestation.1200 1202

-

Importance of informing clinicians of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs.938

-

Importance of informing patients of other important precautionary information.938 (See Cautions.)

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer’s labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Pieces, chewing gum |

227 mg |

Aspergum |

Heritage |

|

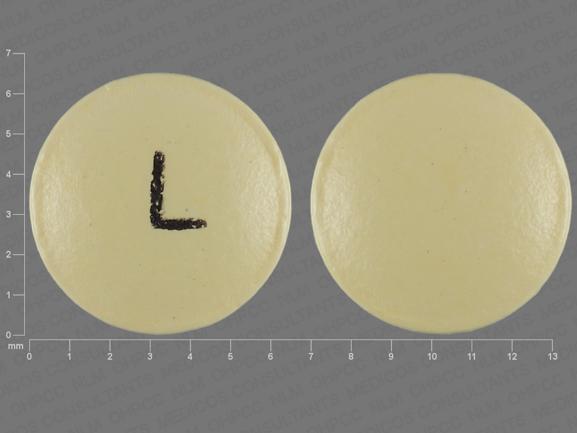

Tablets |

81 mg* |

Aspirin Tablets |

||

|

325 mg* |

Aspirin Tablets |

|||

|

Norwich Aspirin |

Chattem |

|||

|

500 mg* |

Aspirin Tablets |

|||

|

Norwich Aspirin Maximum Strength |

Chattem |

|||

|

650 mg* |

Aspirin Tablets |

|||

|

Tablets, chewable |

81 mg* |

Aspirin Chewable Tablets |

||

|

Bayer Aspirin Children’s |

Bayer |

|||

|

St. Joseph Aspirin Low Strength Adult Chewable |

McNeil |

|||

|

Tablets, delayed-release (enteric-coated) |

81 mg* |

Aspirin Delayed-release (Enteric-coated) Tablets |

||

|

Bayer Aspirin Regimen Adult Low Strength |

Bayer |

|||

|

Ecotrin Adult Low Strength |

GlaxoSmithKline |

|||

|

Halfprin |

Kramer |

|||

|

St. Joseph Pain Reliever Adult |

McNeil |

|||

|

162 mg |

Halfprin |

Kramer |

||

|

325 mg* |

Aspirin Delayed-release (Enteric-coated) Tablets |

|||

|

Bayer Aspirin Regimen Regular Strength Caplets |

Bayer |

|||

|

Ecotrin Regular Strength |

GlaxoSmithKline |

|||

|

Genacote |

Ivax |

|||

|

500 mg* |

Aspirin Delayed-release (Enteric-coated) Tablets |

|||

|

Ecotrin Maximum Strength |

GlaxoSmithKline |

|||

|

650 mg* |

Aspirin Delayed-release (Enteric-coated) Tablets |

|||

|

975 mg* |

Aspirin Delayed-release (Enteric-coated) Tablets |

|||

|

Easprin |

Rosedale |

|||

|

Tablets, extended-release |

800 mg |

ZORprin |

Par |

|

|

Tablets, film-coated |

325 mg* |

Aspirin Tablets |

||

|

Genuine Bayer Aspirin Tablets |

Bayer |

|||

|

500 mg |

Bayer Extra Strength Aspirin Caplets |

Bayer |

||

|

Rectal |

Suppositories |

60 mg* |

Aspirin Suppositories |

|

|

120 mg* |

Aspirin Suppositories |

|||

|

200 mg* |

Aspirin Suppositories |

|||

|

300 mg* |

Aspirin Suppositories |

|||

|

600 mg* |

Aspirin Suppositories |

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Tablets, enteric-coated |

325 mg with buffers |

Ascriptin Enteric Regular Strength |

Novartis |

|

Tablets, film-coated |

81 mg with buffers |

Women’s Bayer Aspirin Plus Calcium Caplets |

Bayer |

|

|

325 mg with buffers |

Ascriptin Arthritis Pain Caplets |

Novartis |

||

|

Ascriptin Regular Strength |

Novartis |

|||

|

Bufferin Tablets |

Novartis |

|||

|

500 mg with buffers |

Ascriptin Maximum Strength Caplets |

Novartis |

||

|

Bayer Plus Extra Strength Caplets |

Bayer |

|||

|

Bufferin Extra Strength Caplets |

Novartis |

|||

|

Bufferin Extra Strength |

Novartis |

|||

|

Tablets, for solution |

325 mg |

Alka-Seltzer Effervescent Pain Reliever and Antacid |

Bayer |

|

|

Alka-Seltzer Lemon Lime Effervescent Pain Reliever and Antacid |

Bayer |

|||

|

500 mg |

Alka-Seltzer Extra Strength Effervescent Pain Reliever and Antacid |

Bayer |

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

For solution |

325 mg/packet Acetaminophen and Aspirin 500 mg/packet |

Goody’s Back & Body Pain Powder |

Prestige |

|

Tablets, film-coated |

250 mg Acetaminophen, Aspirin 250 mg, and buffer |

Excedrin Back and Body Caplets |

Novartis |

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Capsules, gel-coated |

250 mg Acetaminophen, Aspirin 250 mg, and Caffeine 65 mg* |

Acetaminophen, Aspirin, and Caffeine Gelcaps |

|

|

Excedrin Menstrual Complete Gelcaps |

Novartis |

|||

|

For solution |

260 mg/packet Acetaminophen, Aspirin 520 mg/packet, and Caffeine 32.5 mg/packet |

Goody’s Extra Strength Headache Powder |

Prestige |

|

|

325 mg/packet Acetaminophen, Aspirin 500 mg/packet, and Caffeine 65 mg/packet |

Goody’s Cool Orange Extra Strength Powder |

Prestige |

||

|

Tablets, film-coated |

194 mg Acetaminophen, Aspirin 227 mg, Caffeine 33 mg, and buffers |

Vanquish Caplets |

Moberg |

|

|

250 mg Acetaminophen, Aspirin 250 mg, and Caffeine 65 mg |

Excedrin Extra Strength Caplets |

Novartis |

||

|

Excedrin Migraine Caplets |

Novartis |

|||

|

Goody's Extra Strength Caplets |

Prestige |

|||

|

Pamprin Max |

Chattem |

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Tablets |

4.8355 mg Oxycodone Hydrochloride and Aspirin 325 mg* |

Endodan ( C-II ) |

Qualitest |

|

Oxycodone Hydrochloride and Aspirin Tablets ( C-II ) |

||||

|

Percodan ( C-II; scored) |

Endo |

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Capsules |

325 mg with Butalbital 50 mg and Caffeine 40 mg* |

Butalbital, Aspirin, and Caffeine Capsules ( C-III ) |

|

|

Fiorinal ( C-III ) |

Actavis |

|||

|

325 mg with Butalbital 50 mg, Caffeine 40 mg, and Codeine Phosphate 30 mg* |

Butalbital, Aspirin, Caffeine, and Codeine Phosphate Capsules ( C-III ) |

|||

|

Fiorinal with Codeine ( C-III ) |

Actavis |

|||

|

356.4 mg with Caffeine 30 mg and Dihydrocodeine Bitartrate 16 mg |

Synalgos-DC ( C-III ) |

Leitner |

||

|

Capsules, extended-release core (dipyridamole only) |

25 mg with Dipyridamole 200 mg |

Aggrenox |

Boehringer Ingelheim |

|

|

For solution |

845 mg/packet with Caffeine 65 mg/packet |

BC Powder |

Prestige |

|

|

Stanback Powder |

Prestige |

|||

|

1000 mg/packet with Caffeine 65 mg/packet |

BC Powder Arthritis Strength |

Prestige |

||

|

Tablets |

325 mg with Butalbital 50 mg and Caffeine 40 mg* |

Butalbital, Aspirin, and Caffeine Tablets ( C-III ) |

||

|

Fortabs ( C-III ) |

United Research |

|||

|

325 mg with Carisoprodol 200 mg* |

Carisoprodol and Aspirin Tablets ( C-IV ) |

|||

|

Soma Compound ( C-IV ) |

Meda |

|||

|

325 mg with Carisoprodol 200 mg and Codeine Phosphate 16 mg* |

Carisoprodol, Aspirin, and Codeine Phosphate Tablets ( C-III ) |

|||

|

Soma Compound with Codeine ( C-III ) |

Meda |

|||

|

325 mg with Meprobamate 200 mg |

Equagesic ( C-IV; scored) |

Leitner |

||

|

Micrainin ( C-IV ) |

Wallace |

|||

|

385 mg with Caffeine 30 mg and Orphenadrine Citrate 25 mg* |

Norgesic |

3M |

||

|

Orphenadrine Citrate, Aspirin, and Caffeine Tablets |

Sandoz |

|||

|

400 mg with Caffeine 32 mg |

P-A-C Analgesic |

Lee |

||

|

770 mg with Caffeine 60 mg, and Orphenadrine Citrate 50 mg* |

Norgesic Forte (scored) |

3M |

||

|

Orphenadrine Citrate, Aspirin, and Caffeine Tablets |

Sandoz |

|||

|

Tablets, film-coated |

400 mg with Caffeine 32 mg |

Anacin Caplets |

Wyeth |

|

|

Anacin Tablets |

Wyeth |

|||

|

421 mg with Caffeine 32 mg and buffers |

Cope |

Lee |

||

|

500 mg with Caffeine 32 mg |

Anacin Maximum Strength |

Wyeth |

||

|

500 mg with Caffeine 32.5 mg |

Extra Strength Bayer Back and Body Pain (with propylene glycol) |

Bayer |

||

|

Tablets, for solution |

500 mg with Caffeine 65 mg |

Alka Seltzer Morning Relief |

Bayer |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions September 10, 2024. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

Only references cited for selected revisions after 1984 are available electronically.

166. Centers for Disease Control. Reye syndrome—Ohio, Michigan. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1980; 29:532-9.

167. Starko KM, Ray CG, Dominguez LB et al. Reye’s syndrome and salicylate use. Pediatrics. 1980; 66:859-64. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7454476

168. Partin JS, Schubert WK, Partin JC et al. Serum salicylate concentrations in Reye’s disease: a study of 130 biopsy-proven cases. Lancet. 1982; 1:191-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6119559

169. Centers for Disease Control. National surveillance for Reye syndrome, 1981—update, Reye syndrome and salicylate usage. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1982; 31:53-61. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6799770

466. Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Aspirin and Reye syndrome. Pediatrics. 1982; 69:810-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7079050

467. Centers for Disease Control. Surgeon General’s advisory on the use of salicylates and Reye syndrome. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1982; 31:289-90. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6810083

468. Waldman RJ, Hall WN, McGee H et al. Aspirin as a risk factor in Reye’s syndrome. JAMA. 1982; 247:3089-04. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7077803

469. Andresen BD, Alexander MS, Ng KJ et al. Aspirin and Reye’s disease: a reinterpretation. Lancet. 1982; 1:903. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6122113

470. Wilson JT, Brown RD. Reye syndrome and aspirin use: the role of prodromal illness severity in the assessment of relative risk. Pediatrics. 1982; 69:822-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7079054

527. O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013; 127:e362-425.

529. Daniels SR, Greenberg RS, Ibrahim MA. Scientific uncertainties in the studies of salicylate use and Reye’s syndrome. JAMA. 1983; 249:1311-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6827709

537. Remington PL, Rowley D, McGee H et al. Decreasing trends in Reye syndrome and aspirin use in Michigan, 1979 to 1984. Pediatrics. 1986; 77:93-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3940363

538. Hurwitz ES, Barrett MJ, Bregman D et al. Public Health Service study on Reye’s syndrome and medications: report of the pilot phase. N Engl J Med. 1985; 313:849-57. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4033715

539. Food and Drug Administration. Labeling for oral and rectal over-the-counter aspirin and aspirin-containing drug products. [21 CFR Part 201] Fed Regist. 1986; 51:8180-2. (IDIS 211617)

549. Hurwitz ES, Barrett MJ, Bregman D et al. Public Health Service study of Reye’s syndrome and medications: report of the main study. JAMA. 1987; 257:1905-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3820509

550. Orlowski JP, Gillis J, Kilham HA. A catch in the Reye. Pediatrics. 1987; 80:638-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3670965

551. Barrett MJ, Hurwitz ES, Schonberger LB et al. Changing epidemiology of Reye syndrome in the United States. Pediatrics. 1986; 77:598-602. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3960627

552. Arrowsmith JB, Kennedy DL, Kuritsky JN et al. National patterns of aspirin use and Reye syndrome reporting, United States, 1980 to 1985. Pediatrics. 1987; 79:858-63. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3588140

553. Centers for Disease Control. Reye syndrome surveillance—United States, 1986. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1987; 36:687-91.

554. Glen-Bott AM. Aspirin and Reye’s syndrome: a reappraisal. Med Toxicol Adverse Drug Exp. 1987; 2:161-5.

555. Sweeney KR, Chapron DJ, Brandt JL et al. Toxic interaction between acetazolamide and salicylate: case reports and a pharmacokinetic explanation. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1986; 40:518-24. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3769383

556. Fitzgerald GA. Dipyridamole. N Engl J Med. 1987; 316:1247-57. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3553945

557. Stein PD, Collins JJ, Kantrowitz A. American College of Chest Physicians and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Conference on Antithrombotic Therapy. Antithrombotic therapy in mechanical and biological prosthetic heart valves and saphenous vein bypass grafts. Chest. 1986; 89(Suppl):46-53S.

558. Hirsch J, Fuster V, Salzman E. American College of Chest Physicians and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Conference on Antithrombotic Therapy. Dose antiplatelet agents: the relationship among side effects, and antithrombotic effectiveness. Chest. 1986; 89(Suppl):4-10S. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3510108

559. Chesebro JH, Steele PM, Fuster V. Platelet-inhibitor therapy in cardiovascular disease: effective defense against thromboembolism. Postgrad Med. 1985; 78:48-50,57-71. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3160013

560. Chesebro JE, Clements IP, Fuster V et al. A platelet-inhibitor drug trial in coronary-artery bypass operations. N Engl J Med. 1982; 307:73-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7045659

561. Chesebro JH, Fuster V, Elverback LR et al. Effect of dipyridamole and aspirin on late vein-graft patency after coronary bypass operations. N Engl J Med. 1984; 310:209-14. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6361561

562. Chesebro JH, Fuster V, Elverback LR. Dipyridamole and aspirin and patency of coronary bypass grafts. N Engl J Med. 1984; 310:1534. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6538932

563. Brown BG, Cukingnan RA, DeRouen T et al. Improved graft patency in patients treated with platelet-inhibiting therapy after coronary bypass surgery. Circulation. 1985; 72:138-46. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3874009

564. The American-Canadian Co-operative Study Group. Persantine aspirin trial in cerebral ischemia. Part II: endpoint results. Stroke. 1985; 16:406-15. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2860740

565. The ESPS Study Group. The European stroke prevention study (ESPS): principal end-points. Lancet. 1987; 2:1351-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2890951

566. Grotta JC. Current medical and surgical therapy for cerebrovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1987; 317:1505-16. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3317048

567. Fields WS. Dipyridamole. N Engl J Med. 1987; 317:1735.

568. Goldberg TH. Dipyridamole. N Engl J Med. 1987; 317:1735.

569. Genton E, Clagett GP, Salzman EW. American College of Chest Physicians and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Conference on Antithrombotic Therapy. Antithrombotic therapy in peripheral vascular disease. Chest. 1986; 89(Suppl):75-81S. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3940794

570. Sherman DG, Dyken ML, Fisher M et al. American College of Chest Physicians and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Conference on Antithrombotic Therapy. Cerebral embolism. Chest. 1986; 89(Suppl):82-98S.

571. Anon. Doubts about dipyridamole as an antithrombotic drug. Drug Ther Bull. 1984; 22:25-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6368165

572. Rivey MP, Alexander MR, Taylor JW. Dipyridamole: a critical evaluation. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1984; 18:869-80. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6389068

573. The Steering Committee of the Physicians’ Health Study Research Group. Preliminary report: findings from the aspirin component of the ongoing physicians’ health study. N Engl J Med. 1988; 318:262-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3275899

574. Relman AS. Aspirin for the primary prevention of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1988; 318:245-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3275897

575. Peto R, Gray R, Collins R et al. Randomised trial of prophylactic daily aspirin in British male doctors. BMJ. 1988; 296:313-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3125882

576. Orme M. Aspirin all round. BMJ. 1988; 296:307-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3125876

577. UK-TIA Study Group. United Kingdom transient ischaemic attack (UK-TIA) aspirin trial: interim results. BMJ. 1988; 296:316-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2894232

578. Anon. Labeling for oral and rectal over-the-counter aspirin and aspirin-containing drug products: Reye syndrome warning. Fed Regist. 1988; 53:21633-7.

579. ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of IV streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17 187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2. Lancet. 1988; 2:349-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2899772

580. Genentech, Inc. Activase (alteplase, recombinant: a tissue plasminogen activator) prescribing information. South San Francisco, CA; 1988 Jun.

581. Topol EJ, Califf RM, George BS et al. A randomized trial of immediate versus delayed elective angioplasty after IV tissue plasminogen activator in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1987; 317:581-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2956516

582. Guerci AD, Gerstenblith G, Brinker JA et al. A randomized trial of IV tissue plasminogen activator for acute myocardial infarction with subsequent randomization to elective coronary angioplasty. N Engl J Med. 1987; 317:1613-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2960897

583. Williams DO, Borer J, Braunwald E et al. IV recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a report from the NHLBI thrombolysis in myocardial infarction trial. Circulation. 1986; 73:338-46. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3080261

584. Chesebro JH, Knatterud G, Roberts R et al. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Trial, Phase I: a comparison between IV tissue plasminogen activator and IV streptokinase. Clinical findings through hospital discharge. Circulation. 1987; 76:142-54. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3109764

585. Mueller HS, Rao AK, Forman SA et al. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI): comparative studies of coronary reperfusion and systemic fibrinogenolysis with two forms of recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987; 10:479-90. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3114349

586. Mueller HS. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI): update 1987. Klin Wochenschr. 1988; 66(Suppl XII):93- 101. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3126350

587. Kabivitrum, Inc. Kabikinase (streptokinase) prescribing information. Alameda, CA; 1987 Nov.

588. Hoechst-Roussel Pharmaceuticals Inc. Streptase (streptokinase) prescribing information. Somerville, NJ; 1987 Nov.

589. Van de Werf F, Arnold AER. IV tissue plasminogen activator and size of infarct, left ventricular function, and survival in acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1988; 297:1374-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3146370

590. Van de Werf F, European Cooperative Study Group for Recombinant Tissue-Type Plasminogen Activator. Lessons from the European Cooperative recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rt-PA) versus placebo trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988; 12:14A-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3142943

591. Marder VJ, Sherry S. Thrombolytic therapy: current status (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1988; 318:1512-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3285216

592. Loscalzo J, Braunwald E. Tissue plasminogen activator. N Engl J Med. 1988; 319:925-31. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3138537

593. Sobel BE. Pharmacologic thrombolysis: tissue-type plasminogen activator. Circulation. 1987; 76(Suppl II):II-39- 43.

594. Lubbe WF. Prevention of preeclampsia by low dose aspirin. N Z Med J. 1990; 103:237-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2188173