Zolpidem (Monograph)

Brand names: Ambien, Ambien CR, Edluar

Drug class: Non-benzodiazepine Hypnotics

Warning

- Risk of Serious Injury and Death Resulting From Complex Sleep Behaviors

-

Serious injuries and/or death resulting from complex sleep behaviors (e.g., sleepwalking, sleep driving, and engaging in other activities while not fully awake) can occur following use of eszopiclone, zaleplon, and zolpidem.1 89 93 94 200

-

Complex sleep behaviors have occurred in patients with and without a history of such behaviors and can occur even at the lowest recommended doses and after just one dose of these drugs.1 89 93 94 200

-

Discontinue drug immediately if a complex sleep behavior occurs.1 89 93 94 200

Introduction

Imidazopyridine-derivative sedative and hypnotic;1 2 3 4 89 type A GABA (GABAA)-receptor positive modulator;1 89 93 structurally unrelated to benzodiazepines and other sedatives and hypnotics.2 3 94

Uses for Zolpidem

Insomnia

Conventional tablets and sublingual tablets (5 and 10 mg) are used for short-term management of insomnia characterized by difficulties with sleep initiation.1 93 Decreases sleep latency in patients with chronic or transient insomnia;1 2 3 22 no substantial evidence of diminished effectiveness during the end of each night’s use (early morning insomnia) despite short half-life.1 14 19 20

Extended-release tablets are used for short-term management of insomnia characterized by difficulty with sleep onset or sleep maintenance.89 97 May not be an appropriate treatment choice for patients (men or women) who need to drive or perform activities that require full alertness the next morning.95

Sublingual tablets (1.75 and 3.5 mg) are used as needed for management of insomnia when middle-of-the-night awakening is followed by difficulty returning to sleep; use only when ≥4 hours remain before planned time of awakening.94 98 99

Psychological and behavioral interventions are recommended as initial treatment for insomnia according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) and American College of Physicians (ACP) guidelines.204 205 206 When pharmacologic therapy is indicated, choice of agent should be directed by symptoms, treatment goals, past treatment response, patient preference, drug cost and availability, comorbid conditions/contraindications, concomitant drug therapy/interactions, and potential adverse effects.204 205 Zolpidem is among several agents recommended for treatment of sleep onset or sleep maintenance insomnia.204 205 206 The lowest effective dosage and short-term treatment (4–5 weeks) is recommended.204 206

Zolpidem Dosage and Administration

General

Pretreatment Screening

-

Consider the risk of respiratory depression prior to use of zolpidem in patients with respiratory impairment, including those with sleep apnea or myasthenia gravis or in those receiving concomitant opiates or other CNS depressants.1 89

Patient Monitoring

-

Monitor for excessive CNS depression.89

-

Monitor for abnormal thinking and behavioral changes; carefully and immediately evaluate any new and concerning behavioral sign or symptom.1 89

Dispensing and Administration Precautions

-

The 2023 American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication (PIM) Use in Older Adults includes zolpidem on the list of PIMs that are best avoided by older adults in most circumstances or under specific situations, such as certain diseases, conditions, or care settings.999 The criteria are intended to apply to adults 65 years of age and older in all ambulatory, acute, and institutional settings of care, except hospice and end-of-life care settings.999 The Beers Criteria Expert Panel recommends avoiding use of all nonbenzodiazepine benzodiazepine receptor agonist hypnotics (“Z-drugs”; eszopiclone, zaleplon, zolpidem) since these drugs have similar adverse effects to the benzodiazepines in older adults (e.g., delirium, falls, fractures, increased emergency room visits/hospitalizations, motor vehicle crashes) and provide minimal improvement in sleep latency and duration.999

Other General Considerations

-

Reevaluate patient if zolpidem is to be used for more than 2–3 weeks.23 79

-

Consider gradual dosage reduction (e.g., over several nights) when discontinuing therapy.1 77 78

Administration

Administer orally (as conventional tablets or extended-release tablets) or sublingually (as sublingual tablets).1 89 93 94

Oral Administration

Do not administer with or immediately after a meal in order to facilitate onset of sleep.1 89

Conventional Tablets

Administer only once per night immediately before bedtime, at least 7–8 hours before planned time of awakening.1

Extended-release Tablets

Administer only once per night immediately before bedtime, at least 7–8 hours before planned time of awakening.89

Swallow extended-release tablets whole; do not divide, crush, or chew.89

Sublingual Administration

Do not administer with or immediately after a meal in order to facilitate onset of sleep.93 94

Sublingual Tablets (5 and 10 mg)

Administer only once per night immediately before bedtime, at least 7–8 hours before planned time of awakening.93

Place tablet under tongue, where it will disintegrate.93 Do not swallow or administer tablet with water.93

Sublingual Tablets (1.75 and 3.5 mg)

Administer in bed, only once per night as needed if middle-of-the-night awakening is followed by difficulty returning to sleep, and only if ≥4 hours remain before planned time of awakening.94

Place tablet under tongue and allow to disintegrate completely before swallowing.94 Do not swallow tablet whole.94

Remove tablet from pouch just prior to administration.94

Dosage

Available as zolpidem tartrate; dosage expressed in terms of the salt.1 89 93 94

Use the lowest effective dosage and shortest duration of treatment possible.1 89 93 95 200 Do not use for extended duration without reevaluation of patient status; risk of abuse and dependence increases with duration of treatment.1 89

Adults

Insomnia

Difficulty with Sleep Initiation

Oral (Conventional Tablets) or Sublingual (5 and 10 mg Sublingual Tablets)Women: Initially, single 5-mg dose.1 93 95

Men: Initially, single 5- or 10-mg dose.1 93 95

If 5 mg is not effective in men or women, may increase dose to 10 mg.1 93 95

In some patients, higher morning blood concentrations following a 10-mg dose increase risk of next-day impairment of driving and other activities requiring full alertness.1 93 95

Initial doses for women and men differ because clearance is slower in women.1 93 95

Difficulty with Sleep Initiation or Sleep Maintenance

Oral (Extended-release Tablets)Women: Initially, single 6.25-mg dose.89 95

Men: Initially, single 6.25- or 12.5-mg dose.89 95

If 6.25 mg is not effective in men or women, may increase dose to 12.5 mg.89 95

In some patients, higher morning blood concentrations following a 12.5-mg dose increase risk of next-day impairment of driving and other activities requiring full alertness.89 95

Initial doses for women and men differ because clearance is slower in women.89 95

Middle-of-the-Night Awakening

Sublingual (1.75 and 3.5 mg Sublingual Tablets)Women: 1.75 mg.94

Men: 3.5 mg.94

Doses for women and men differ because clearance is slower in women.94

Men or women receiving concomitant CNS depressant: 1.75 mg.94

Prescribing Limits

Adults

Insomnia

Difficulty with Sleep Initiation

Oral (Conventional Tablets) or Sublingual (5 and 10 mg Sublingual Tablets)Maximum 10 mg once daily immediately before bedtime.1 93

Difficulty with Sleep Initiation or Sleep Maintenance

Oral (Extended-release Tablets)Maximum 12.5 mg once daily immediately before bedtime.89

Middle-of-the-Night Awakening

Sublingual (1.75 and 3.5 mg Sublingual Tablets)Women: Maximum 1.75 mg once per night.94

Men: Maximum 3.5 mg once per night.94

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

Conventional tablets In patients with mild or moderate hepatic impairment, 5 mg once daily immediately before bedtime.1 Avoid use in patients with severe hepatic impairment.1

Extended-release tablets: In patients with mild or moderate hepatic impairment, 6.25 mg once daily immediately before bedtime.89 Avoid use in patients with severe hepatic impairment.89

Sublingual tablets for insomnia characterized by difficulties with sleep initiation: 5 mg once daily immediately before bedtime.93

Sublingual tablets for middle-of-the-night awakening: 1.75 mg only once per night if needed.94

Renal Impairment

Possible pharmacokinetic alterations.2 3 81 Manufacturers state that dosage adjustment is not necessary;1 89 93 94 some clinicians recommend that dosage reduction be considered.2 3 81

Geriatric Patients

Possible increased sensitivity to sedatives and hypnotics.1 89 93 94

Conventional tablets: 5 mg once daily immediately before bedtime.1

Extended-release tablets: 6.25 mg once daily immediately before bedtime.89

Sublingual tablets for insomnia characterized by difficulties with sleep initiation: 5 mg once daily immediately before bedtime.93

Sublingual tablets for middle-of-the-night awakening: In men and women >65 years of age, 1.75 mg only once per night if needed.94

Debilitated Patients

Possible increased sensitivity to sedatives and hypnotics.1 89 93

Conventional tablets: 5 mg once daily immediately before bedtime.1

Extended-release tablets: 6.25 mg once daily immediately before bedtime.89

Sublingual tablets for insomnia characterized by difficulties with sleep initiation: 5 mg once daily immediately before bedtime.93

Cautions for Zolpidem

Contraindications

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Complex Sleep Behaviors

Complex sleep behaviors, in which patients engage in activities while they are not fully awake, reported in patients taking hypnotic-sedative agents; some cases may result in serious injuries and/or death.1 89 93 94 200 201 202 203 (See Boxed Warning.) Such behaviors may include sleepwalking, sleep driving (i.e., driving while not fully awake after ingesting a sedative-hypnotic drug, with no memory of the event), and engaging in other activities (e.g., making phone calls, preparing and eating food).1 89 93 94 200 201 202 203

Falls with serious injuries such as intracranial hemorrhages, vertebral fractures, and hip fractures as well as fatal falls, self-injuries, accidental overdoses, hypothermia, suicide attempts and apparent completed suicides, fatal motor vehicle collisions, gunshot wounds, carbon monoxide poisoning, drowning or near drowning, burns, and homicide have been reported to FDA.200 201 202 203

Reported in patients with or without a history of such behaviors and even at the lowest recommended dosages or after just one dose.200

Can occur when these drugs are taken alone or with alcohol or other CNS depressants.1 89 93 94 200

Discontinue zolpidem immediately if a complex sleep behavior occurs.1 89 93 94 200

Other Warnings and Precautions

CNS Depression and Next-day Impairment

CNS depressant; may impair daytime function in some patients even when used as prescribed.1 89 93 94 95 96

Zolpidem blood concentrations >50 ng/mL may impair driving to a degree that increases risk of a motor vehicle accident.95 Concentrations >50 ng/mL reported at 8 hours after a dose in 15% of women and 3% of men receiving 10 mg (as conventional tablets); in 33% of women and 25% of men receiving 12.5 mg (as extended-release tablets); and in 15% of nongeriatric women, 5% of nongeriatric men, and 10% of both geriatric men and women receiving 6.25 mg (as extended-release tablets).95 Some patients had concentrations ≥90 or ≥100 ng/mL.95 Because of these findings, bedtime dosages currently recommended by the manufacturers and FDA are lower than original labeled dosages.95 96

Impaired driving reported when driving test administered to healthy individuals <4 hours after a 3.5-mg sublingual dose;94 potential driving impairment at 4 hours after recommended 1.75-mg dose in women or 3.5-mg dose in men cannot be completely excluded.94

Use smallest effective dose to decrease potential risk of next-day impairment.95

Monitor patients for excessive CNS depression; however, impairment may occur in the absence of symptoms and may not be reliably detected by ordinary clinical examination (i.e., formal psychomotor testing may be required).89

Concurrent use of other CNS depressants (e.g., alcohol, benzodiazepines, opiates, tricyclic antidepressants) increases risk of CNS depression.1 89 93 94 Dosage adjustments of zolpidem and concurrent CNS depressants may be necessary.1 89 93 94

Concomitant use with other sedatives and hypnotics (including other zolpidem-containing preparations and OTC preparations used to treat insomnia [e.g., diphenhydramine, doxylamine succinate]) at bedtime or in middle of the night is not recommended.1 89 93 94 200

Women appear to be more susceptible to next-day psychomotor impairment because zolpidem clearance is slower in women than in men.95

Administration as extended-release tablets increases risk of next-day impairment.89 Extended-release zolpidem may not be an appropriate treatment choice for patients who need to drive or perform activities that require full alertness the next morning.95 Drug concentrations may remain high enough the next day to impair performance.89 96

Risk of next-day impairment is increased if preparations intended for bedtime administration (e.g., conventional or extended-release tablets, 5- or 10-mg sublingual tablets) are administered with less than 7–8 hours of sleep time remaining, if preparations intended for middle-of-the-night administration (1.75- or 3.5-mg sublingual tablets) are administered with <4 hours of sleep time remaining, if higher than recommended dose is administered, or if used concomitantly with other CNS depressants (including alcohol) or drugs that increase zolpidem concentrations.1 89 93 94

Warn vehicle drivers and machine operators that, as with other hypnotics, there may be a possible risk of adverse reactions including drowsiness, prolonged reaction time, dizziness, sleepiness, blurred/double vision, reduced alertness, and impaired driving the morning after therapy.1 89 In order to minimize this risk a full night of sleep (7–8 hours) is recommended.1 89

Drowsiness and decreased levels of consciousness associated with zolpidem may result in an increased risk of falls, particularly in geriatric patients.1 89 93 94

Adequate Patient Evaluation

Insomnia may be a manifestation of an underlying physical and/or psychiatric disorder; carefully evaluate patient before providing symptomatic treatment.1 23 79 89

Failure of insomnia to remit after 7–10 days of treatment, worsening of insomnia, or emergence of new thinking or behavioral abnormalities may indicate the presence of an underlying psychiatric and/or medical condition that requires evaluation.1 89

Severe Hypersensitivity Reactions

Angioedema involving the tongue, glottis, or larynx reported following initial or subsequent doses of sedative and hypnotic drugs, including zolpidem; may result in airway obstruction and death.1 89 91 Anaphylaxis also reported.1 89 91

Do not rechallenge with the drug if angioedema occurs.1 89 91

Abnormal Thinking and Behavioral Changes

Abnormal thinking and behavioral changes (e.g., decreased inhibition, aggressiveness, uncharacteristic extroversion, bizarre behavior, agitation, depersonalization, visual and auditory hallucinations) reported in patients receiving sedative and hypnotic drugs, including zolpidem.1 4 89 Amnesia, anxiety, and other neuropsychiatric symptoms may occur.1 89 Cases of delirium also reported.1 89

Carefully and immediately evaluate any new and concerning behavioral sign or symptom.1 89

Use in Patients with Depression

Worsening of depression and suicidal thoughts and actions (including completed suicides) reported in primarily depressed patients receiving sedatives and hypnotics.1 89 Suicidal tendencies may be present; intentional overdosage more frequent in such patients.1 89 Protective measures may be required.1 89 Prescribe and dispense drug in the smallest feasible quantity.1 89

Respiratory Depression

No respiratory depressant effects reported following 10-mg doses in healthy individuals or patients with mild to moderate COPD;1 85 89 however, decreased oxygen saturation reported in patients with mild to moderate sleep apnea.1 86 89 Respiratory insufficiency reported, mostly in patients with preexisting respiratory impairment.1 89

Use with caution in patients with compromised respiratory function and in patients receiving concomitant opiates or other CNS depressants; sedatives and hypnotics may depress respiratory drive.1 89

Consider risk of respiratory depression prior to use in patients with respiratory impairment (e.g., sleep apnea, myasthenia gravis) or in those receiving concomitant opiates or other CNS depressants.1 89

Precipitation of Hepatic Encephalopathy

Precipitation of hepatic encephalopathy reported in patients with hepatic insufficiency receiving drugs affecting GABA receptors (e.g., zolpidem tartrate).1 89 In addition, zolpidem is eliminated more slowly in patients with hepatic insufficiency.1 89

Manufacturer of conventional and extended-release tablets states to avoid use in patients with severe hepatic impairment.1 89

Withdrawal Effects

Signs and symptoms of withdrawal reported following rapid dosage reduction or abrupt discontinuance; monitor patients for tolerance and dependence.1 89

Abuse Potential

May lead to development of physical and/or psychological dependence; risk of dependence increases with dose and duration of treatment and is greater in patients with a history of alcohol or drug abuse.1 89

Zolpidem tartrate 40 mg and diazepam 20 mg (as single doses) had similar effects in former drug abusers; effects of zolpidem tartrate 10 mg and placebo were difficult to distinguish.1 89 Monitor patients for abuse.1 89

Increased risk for misuse and abuse of and addiction to zolpidem in patients with current or past history of addiction to or abuse of drugs or alcohol; use with extreme caution in such patients.1 89

Do not use for extended duration without reevaluation of patient status; risk of abuse and dependence increases with duration of treatment.1 89

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Available evidence shows no clear association between zolpidem use during pregnancy and major birth defects.1 89 93 No adverse fetal developmental effects observed in animal reproduction studies.1 89 93

Zolpidem crosses the placenta and may cause respiratory depression and sedation in neonates.1 89 93 Monitor neonates exposed to zolpidem during pregnancy and labor for signs of excess sedation, hypotonia, and respiratory depression and treat as clinically indicated.1 89 93

Lactation

Distributed into milk in small amounts;1 84 89 93 94 100 excess sedation reported in nursing infants.1 89 93 Effects of zolpidem on milk production not known.1 89 93

Consider the developmental and health benefits of breast-feeding along with the mother’s clinical need for zolpidem and any potential adverse effects on the breast-fed infant from the drug or underlying maternal condition.1 89 93

Monitor infants exposed to zolpidem through breast-feeding for excess sedation, hypotonia, and respiratory depression.1 89 93

Nursing women may consider interrupting breast-feeding and pumping and discarding breast milk during treatment and for 23 hours after administration of zolpidem to minimize drug exposure to a breast-fed infant.1 89 93

Pediatric Use

Not recommended in pediatric patients.1 89 93 94

Safety and efficacy not established in pediatric patients <18 years of age.1 89 93 94 Dizziness, headache, and hallucinations reported.1 89

Geriatric Use

Pharmacokinetic changes in geriatric patients compared with younger adults.1

Potential increased sensitivity to zolpidem.1 89 93 94 Adverse effects tend to be dose-related, 1 2 4 9 82 89 particularly in geriatric patients.1 2 9 Adverse effect profile in patients ≥65 years of age receiving 6.25-mg dose (as extended-release tablets) similar to that in younger adults receiving 12.5-mg dose.89

Use reduced dose to minimize adverse effects related to impaired motor and/or cognitive performance and unusual sensitivity to sedative and hypnotic drugs.1 89 93 94 Sedatives may cause confusion and oversedation in geriatric patients; observe closely.94 Geriatric patients are at a higher risk of falls related to drowsiness and CNS depression.1 89 93 94

Hepatic Impairment

Prolonged elimination; reduce dose in patients with mild or moderate hepatic impairment.1 81 89 93 94 Manufacturer states to avoid use of zolpidem conventional or extended-release tablets in patients with severe hepatic impairment; drug may contribute to hepatic encephalopathy.1 89

Renal Impairment

Possible pharmacokinetic alterations.2 3 81 Manufacturers state that dosage adjustment is not necessary;1 89 93 94 however, some clinicians recommend that dosage reduction be considered.2 3 81

Common Adverse Effects

Zolpidem tartrate conventional tablets generally are well tolerated at recommended doses (i.e., up to 10 mg).1 2 9 Adverse effects of the drug tend to be dose-related,1 2 4 9 82 particularly in geriatric patients1 2 9 and at doses exceeding those recommended.2 3 4 9 The most common adverse reactions with zolpidem conventional tablets when used in the short-term (<10 nights) include drowsiness, dizziness, and diarrhea; common adverse reactions reported with long-term use (28–35 nights) of the conventional tablets include dizziness and drugged feeling.1

Adverse effects of zolpidem tartrate as extended-release tablets tend to be dose-related, particularly for certain adverse nervous system and GI effects.89 The most common adverse effects of zolpidem tartrate as extended-release tablets (occurring in >10% of adult patients) include headache, next-day somnolence, and dizziness.89

The incidence of adverse effects in patients receiving zolpidem tartrate as 1.75- or 3.5-mg sublingual tablets were headache, fatigue, and nausea.94

Drug Interactions

Metabolized principally by CYP3A4 and to a lesser extent by CYP1A2 and CYP2D6.88

Drugs Affecting Hepatic Microsomal Enzymes

Some drugs that inhibit CYP3A may increase systemic exposure to zolpidem.1 89 Consider decreasing zolpidem dosage if used concomitantly with a potent CYP3A4 inhibitor.1 89

Some drugs that induce CYP3A may decrease systemic exposure to zolpidem.1 89 Concomitant use with potent CYP3A4 inducers not recommended.1 89

Effect of inhibitors or inducers of other CYP isoenzymes on pharmacokinetics (e.g., systemic exposure) of zolpidem not known.1 89

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Chlorpromazine |

Pharmacokinetic interactions unlikely; however, additive effects in reducing alertness and psychomotor performance1 89 |

|

|

Cimetidine |

No effect on zolpidem pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics1 89 |

|

|

Ciprofloxacin |

||

|

CNS depressants (e.g., alcohol, benzodiazepines, opiates, sedating antihistamines, sedatives and hypnotics, tricyclic antidepressants) |

Increased risk of CNS depression1 89 200 Increased risk of drowsiness and psychomotor impairment, including impaired driving ability1 89 Extended-release zolpidem: Additive effects with concomitant use, including daytime use, of other CNS depressants89 Alcohol: Additive adverse effect on psychomotor performance1 89 |

Avoid concomitant use of other sedatives and hypnotics (including other zolpidem-containing preparations and OTC preparations used to treat insomnia [e.g., diphenhydramine, doxylamine succinate]) at bedtime or in middle of the night1 89 200 Dosage adjustment of zolpidem and other concomitant CNS depressants may be necessary1 89 93 94 When zolpidem used for middle-of-the-night awakening, recommended dose in men or women receiving concomitant CNS depressants is 1.75 mg; dosage adjustment of concomitant CNS depressant may be necessary94 Alcohol: Advise patients not to take zolpidem after consuming alcohol in the evening or before bedtime1 89 93 94 |

|

Digoxin |

||

|

Fluoxetine |

Clinically important pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic (e.g., psychomotor function) interactions not observed in healthy individuals1 89 102 103 |

|

|

Fluvoxamine |

||

|

Haloperidol |

No effect on zolpidem pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics following single dose; does not exclude effect following chronic use1 89 |

|

|

Imipramine |

Decreased imipramine peak concentration but no other pharmacokinetic interactions; however, additive effect in reducing alertness1 89 |

|

|

Itraconazole |

Increased zolpidem AUC, but no changes in psychomotor performance, postural sway, or self-perceived drowsiness1 89 104 |

|

|

Ketoconazole |

Increased peak concentration, AUC, elimination half-life, and pharmacodynamic effects of zolpidem; possible increased hypnotic effects1 89 |

|

|

Ranitidine |

No effect on zolpidem pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics1 89 |

|

|

Rifampin |

Decreased AUC, peak concentration, half-life, and pharmacodynamic effects of zolpidem; possible decreased hypnotic efficacy1 89 101 |

|

|

Sertraline |

Earlier and higher peak zolpidem concentrations; possible earlier hypnotic onset and greater hypnotic effect1 89 105 No clinically important effects on pharmacokinetics of sertraline or N-desmethylsertraline1 89 105 |

|

|

St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum) |

||

|

Warfarin |

Zolpidem Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Conventional tablets: Rapidly absorbed from GI tract following oral administration, with peak plasma concentrations attained in about 1.6 hours.1 Absolute bioavailability is about 70%.87

Extended-release tablets: Exhibit biphasic absorption characteristics; rapid initial absorption following oral administration (similar to conventional tablets), but with extended plasma concentrations beyond 3 hours after administration.89 Peak plasma concentrations are attained in about 1.5 hours.89

Sublingual tablets (5 and 10 mg): Bioequivalent to conventional tablets with respect to peak concentration and AUC.93 Rapidly absorbed, with peak plasma concentrations attained in about 82 minutes.93

Sublingual tablets (1.75 and 3.5 mg): Rapidly absorbed, with peak plasma concentrations attained in about 35–75 minutes.94

Food

Conventional tablets: Food decreases AUC by 15%, decreases peak plasma concentration by 25%, and prolongs time to peak plasma concentration by 60%.1

Extended-release tablets: Food decreases AUC by 23%, decreases peak plasma concentration by 30%, and prolongs time to peak plasma concentration by about 2 hours (from 2 hours to 4 hours).89

Sublingual tablets (5 and 10 mg): Food decreases AUC by 20%, decreases peak plasma concentration by 31%, and prolongs time to peak plasma concentration by 28% (from 82 minutes to 105 minutes).93

Sublingual tablets (1.75 and 3.5 mg): Food decreases AUC by 19%, decreases peak plasma concentration by 42%, and prolongs time to peak plasma concentration to nearly 3 hours.94

Plasma Concentrations

Blood concentrations >50 ng/mL may impair driving to a degree that increases risk of a motor vehicle accident.95 (See CNS Depression and Next-day Impairment under Cautions.)

Special Populations

Zolpidem exposure is greater in women than in men receiving the same dose.1 89 93 94 Peak concentration and AUC are increased by 45% (for immediate-release formulation) or by 50 and 75%, respectively (for extended-release tablets), in women compared with men;1 93 94 concentrations 6–12 hours after a dose of extended-release zolpidem are 2–3 times higher in women than in men.89

Zolpidem exposure is greater in geriatric patients than in younger adults receiving the same dose.1 94 Peak concentration and AUC are increased by 50 and 64%, respectively (for conventional tablets), and by 34 and 30%, respectively (for 3.5-mg sublingual tablets), in geriatric individuals compared with younger adults.1 94 Peak concentrations and AUC are lower in geriatric individuals receiving 1.75-mg dose than in younger adults receiving 3.5-mg dose.94

In patients with chronic hepatic impairment, peak plasma concentration and AUC (for conventional tablets) are 2 and 5 times higher, respectively, than in healthy individuals.1 89 Extended-release tablets not studied to date in patients with hepatic impairment.89

Distribution

Extent

Distributed into milk in small amounts.1 89 93 94 100

Plasma Protein Binding

Approximately 92–93%.1 87 89 93 94

Elimination

Metabolism

Metabolized in the liver via oxidation and hydroxylation, principally by CYP3A4 and to a lesser extent by CYP1A2 and CYP2D6.1 88 No active metabolites.1 87 89 93 94

Elimination Route

Excreted principally in urine as inactive metabolites.1 89 93 94

Half-life

Approximately 2.5–3 hours.1 87 89 93 94

Special Populations

Eliminated more slowly in women than in men; lower doses recommended for women since use of same dose in women and men would result in greater drug exposure and increased susceptibility to next-day impairment in women.1 89 93 94 95 In geriatric patients, clearance is similar in men and women, and dosage is not gender specific.1 89 93

In geriatric patients receiving zolpidem as conventional or extended-release tablets, half-life is 2.9 hours.1 89 Half-life in geriatric patients reportedly is increased by 32% (for conventional tablets) or unchanged (for 1.75 and 3.5 mg sublingual tablets) compared with younger adults.1 94

In patients with cirrhosis receiving zolpidem as conventional tablets, half-life is about 9.9 hours.1 89 Extended-release tablets not studied to date in patients with hepatic impairment.89

In nondialyzed patients with chronic renal disease and in patients undergoing periodic dialysis, slower elimination rates reported with IV zolpidem (not commercially available in the US).2 3 81 No substantial pharmacokinetic alterations reported with oral zolpidem in patients with end-stage renal failure undergoing hemodialysis.1 89 Extended-release tablets not studied to date in patients with renal impairment.89

Not removed by hemodialysis.1 89

Stability

Storage

Oral

Conventional Tablets

20–25°C.1

Extended-release Tablets

15–25°C (may be exposed to temperatures up to 30°C).89

Sublingual

Sublingual Tablets (5 and 10 mg)

20–25°C.93 Protect from light and moisture.93

Sublingual Tablets (1.75 and 3.5 mg)

20–25°C (may be exposed to 15–30°C).94 Protect from moisture.94

Store tablet in pouch until just prior to administration.94

Actions

-

Interacts with the CNS GABA-benzodiazepine-chloride ionophore receptor complex.1 2 3 89

-

Therapeutic effects in short-term treatment of insomnia thought to occur through binding to the benzodiazepine site of α1 subunit containing GABA A receptors, increasing frequency of chloride channel opening and resulting in inhibition of neuronal excitation.1 89 93

-

Selectivity for the type 1 benzodiazepine (BZ1) receptor not absolute, but may account for the decreased muscle relaxant, anxiolytic, and anticonvulsant effects compared with benzodiazepines reported in animal studies,1 2 3 4 6 7 89 93 94 as well as the preservation of deep sleep (stages 3 and 4) reported in human studies.4 94

Advice to Patients

-

Provide patients with a copy of the medication guide.1 89 93 94 95

-

Inform patients and their families of the benefits and risks of zolpidem therapy.1 89 93 94 95

-

Advise all patients of the potential for next-day impairment, that the risk is increased if dosing instructions are not carefully followed, and that impairment may be present despite feeling fully awake.1 89 93 94 95

-

Advise patients that drowsiness and decreased consciousness may increase the risk of falls in some patients.1 89 93 94

-

Advise patients to administer immediate-release zolpidem preparations intended for bedtime administration (conventional tablets, 5- and 10-mg sublingual tablets) immediately before getting into bed, at least 7–8 hours before being active again.1 93 Wait ≥8 hours after taking the drug before driving or engaging in other activities requiring full mental alertness.1 93

-

Advise patients to administer extended-release zolpidem immediately before getting into bed, at least 7–8 hours before being active again.89 Avoid driving or engaging in other activities requiring complete mental alertness the day after taking this preparation.89

-

Advise patients to administer the 1.75- or 3.5-mg sublingual tablets in bed, only once per night as needed, if middle-of-the-night awakening is followed by difficulty returning to sleep, and only if ≥4 hours remain before planned time of awakening.94 Wait ≥4 hours after taking this preparation and until feeling fully awake before driving or engaging in other activities requiring full mental alertness.94

-

Risk of serious injury and/or death resulting from complex sleep behaviors (e.g., sleep-walking, sleep-driving, preparing and eating food, making phone calls, or having sex while not being fully awake).1 89 93 94 200 Advise patients to discontinue zolpidem and notify a clinician immediately if an episode of complex sleep behavior occurs during therapy, even if it did not result in serious injury.1 89 93 94 200

-

Potential risk of abnormal thinking and behavioral changes; advise patients to immediately inform their clinician if any such changes occur.1 89 91

-

Advise patients to immediately inform their clinician of any suicidal thoughts or memory impairment.1 89

-

Potential risk of severe anaphylactic and anaphylactoid reactions; advise patients to immediately seek medical attention if manifestations of such reactions occur.1 89

-

Instruct patients to take zolpidem only as prescribed; do not increase dosage unless otherwise instructed by a clinician; inform clinician if the drug is not effective.1 89 93 94 95

-

Risk of withdrawal symptoms following abrupt discontinuance or rapid reduction in dosage.1 89 Advise patients to inform their clinician of any tolerance or dependence/withdrawal symptoms.1 89

-

Advise patients to not take zolpidem with or immediately after a meal.1 89 93 94

-

Instruct patients to take zolpidem sublingual tablet (5 or 10 mg) under the tongue and allow it to disintegrate; do not swallow or take with water.93

-

Instruct patients to place zolpidem sublingual tablet (1.75 or 3.5 mg) under the tongue and allow it to disintegrate completely before swallowing; do not swallow whole.94 Remove the tablet from the pouch just prior to dosing.94

-

Advise patients to inform their clinicians of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs, and any concomitant illnesses, particularly depression.1 89

-

Advise patients to not take zolpidem after consuming alcohol in the evening or before bedtime.1 89 93 94 Instruct patients to avoid concurrent use of other sedative and hypnotic drugs used to treat insomnia (including OTC preparations such as diphenhydramine or doxylamine succinate) or CNS depressants during therapy unless otherwise instructed by a clinician.200 Inform patients and caregivers that potentially serious additive effects may occur if zolpidem is used with opiates and not to use such drugs concomitantly with zolpidem unless supervised by a clinician.1 89

-

Advise women to inform their clinician if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1 89 93 94 Advise patients that use of zolpidem late in the third trimester may cause respiratory depression and sedation in neonates.1 89 93 Advise mothers who used zolpidem during the late third trimester of pregnancy to monitor neonates for signs of excess sleepiness, breathing difficulties, or limpness.1 89 93

-

Advise nursing women to monitor infants for increased sleepiness, breathing difficulties, or limpness and to seek immediate medical care if such signs occur.1 89 93 A lactating woman may consider pumping and discarding breast milk during treatment and for 23 hours after zolpidem administration to minimize drug exposure to a breast-fed infant.1 89 93

-

Inform patients of other important precautionary information.1 89 93 94 (See Cautions.)

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer’s labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

Subject to control under the Federal Controlled Substances Act of 1970 as a schedule IV (C-IV) drug.1 89 93 94

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Tablets, extended-release, film-coated |

6.25 mg |

Ambien CR (C-IV) |

Sanofi-Aventis |

|

Zolpidem Tartrate Extended-release Tablets (C-IV) |

||||

|

12.5 mg |

Ambien CR (C-IV) |

Sanofi-Aventis |

||

|

Zolpidem Tartrate Extended-release Tablets (C-IV) |

||||

|

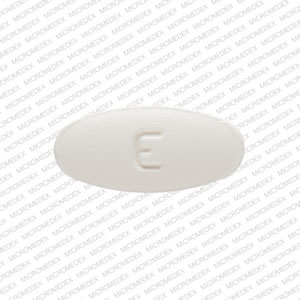

Tablets, film-coated |

5 mg |

Ambien (C-IV) |

Searle |

|

|

Zolpidem Tartrate Tablets (C-IV) |

||||

|

10 mg |

Ambien (C-IV) |

Searle |

||

|

Zolpidem Tartrate Tablets (C-IV) |

||||

|

Sublingual |

Tablets |

1.75 mg* |

Zolpidem Tartrate Sublingual Tablets (C-IV) |

|

|

3.5 mg* |

Zolpidem Tartrate Sublingual Tablets (C-IV) |

|||

|

5 mg* |

Edluar (C-IV) |

Meda |

||

|

Zolpidem Tartrate Sublingual Tablets (C-IV) |

||||

|

10 mg* |

Edluar (C-IV) |

Meda |

||

|

Zolpidem Tartrate Sublingual Tablets (C-IV) |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions June 10, 2025. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

References

1. Sanofi-Aventis. Ambien (zolpidem tartrate) tablet prescribing information. Bridgewater, NJ; 2022 Feb. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/fda/fdaDrugXsl.cfm?setid=404c858c-89ac-4c9d-8a96-8702a28e6e76

2. Langtry HD, Benfield P. Zolpidem: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic potential. Drugs. 1990; 40:291-313. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2226217

3. Fullerton T, Frost M. Focus on zolpidem: a novel agent for the treatment of insomnia. Hosp Formul. 1992; 27:773-91.

4. Anon. Zolpidem for insomnia. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1993; 35:35-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8386301

5. Cavallaro R, Regazzetti MG, Covelli G et al. Tolerance and withdrawal with zolpidem. Lancet. 1993; 342:374- 5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8101619

6. Perrault G, Morel E, Sanger DJ et al. Differences in the pharmacological profiles of a new generation of benzodiazepine and non-benzodiazepine hypnotics. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990; 187:487-94. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1981555

7. Perrault G, Morel E, Sanger DJ et al. Lack of tolerance and physical dependence upon repeated treatment with the novel hypnotic zolpidem. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992; 263:298-303. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1403792

8. Griffiths RR, Sannerud CA, Ator NA et al. Zolpidem behavioral pharmacology in baboons: self-injection, discrimination, tolerance and withdrawal. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992; 260:1199-208. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1312162

9. Scharf MB, Mayleben DW, Kaffeman M et al. Dose response effects of zolpidem in normal geriatric subjects. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991; 52:77-83. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1993640

10. Bensimon G, Foret J, Warot D et al. Daytime wakefulness following a bedtime oral dose of zolpidem 20 mg, flunitrazepam 2 mg and placebo. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1990; 30:463-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2223425

11. Fairweather DB, Kerr JS, Hindmarch I. The effects of acute and repeated doses of zolpidem on subjective sleep, psychomotor performance and cognitive function in elderly volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1992; 43:597-601. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1493840

12. Brunner DP, Dijk DJ, Münch M et al. Effect of zolpidem on sleep and sleep EEG spectra in healthy young men. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1991; 104:1-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1881993

13. Sicard BA, Trocherie S, Moreau J et al. Evaluation of zolpidem on alertness and psychomotor abilities among aviation ground personnel and pilots. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1993; 64:371-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8503809

14. Roger M, Attali P, Coquelin JP. Multicenter, double- blind, controlled comparison of zolpidem and triazolam in elderly patients with insomnia. Clin Ther. 1993; 15:127-36. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8458042

15. Jonas JM, Coleman BS, Sheridan AQ et al. Comparative clinical profiles of triazolam versus other shorter-acting hypnotics. J Clin Psychiatr. 1992; 53(Suppl):19-31.

16. Byrnes JJ, Greenblatt DJ, Miller LG. Benzodiazepine receptor binding of nonbenzodiazepines in vivo: alpidem, zolpidem and zopiclone. Brain Res Bull. 1992; 29:905- 8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1361878

17. Benavides J, Peny B, Durand A et al. Comparative in vivo and in vitro regional selectivity of central omega (benzodiazepine) site ligands in inhibiting [3H]flumazenil binding in the rat central nervous system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992; 263:884-96. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1331419

18. Perrault G, Morel E, Sanger DJ et al. Lack of tolerance and physical dependence upon repeated treatment with the novel hypnotic zolpidem. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992; 263:298-303. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1403792

19. Lader M. Rebound insomnia and newer hypnotics. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1992; 108:248-55. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1523276

20. Maarek L, Cramer P, Attali P et al. The safety and efficacy of zolpidem in insomniac patients: a long-term open study in general practice. J Int Med Res. 1992; 20:162-70. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1521672

21. Wheatley D. Prescribing short-acting hypnosedatives: current recommendations from a safety perspective. Drug Saf. 1992; 7:106-15. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1605897

22. Kryger MH, Steljes D, Pouliot Z et al. Subjective versus objective evaluation of hypnotic efficacy: experience with zolpidem. Sleep. 1991; 14:399-407. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1759092

23. The Upjohn Company. Halcion (triazolam) tablets prescribing information, dated 1991 Dec. In: Physicians’ desk reference. 46th ed. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Company Inc; 1992(Suppl A):A127-30.

24. Greenblatt DJ, Shader RI, Abernethy DR. Drug therapy: current status of benzodiazepines (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1983; 309:354-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6135156

25. Greenblatt DJ, Shader RI, Abernethy DR. Drug therapy: current status of benzodiazepines (second of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1983; 309:410-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6135990

26. Anon. Choice of benzodiazepines. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1988; 30:26-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2893246

27. National Institutes of Health. Drugs and insomnia: the use of medications to promote sleep. Consensus Development Conference. JAMA. 1984; 251:2410-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6142971

28. Kales A, Soldatos CR, Kales JD. Sleep disorders: insomnia, sleepwalking, night terrors, nightmares, and enuresis. Ann Intern Med. 1987; 106:582-92. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3548525

29. Greenblatt DJ, Harmatz JS, Zinny MA et al. Effect of gradual withdrawal on the rebound sleep disorder after discontinuation of triazolam. N Engl J Med. 1987; 317:722-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3306380

30. Kales A, Soldatos CR, Bixler EO et al. Early morning insomnia with rapidly eliminated benzodiazepines. Science. 1983; 20:95-7.

31. Kales A, Scharf MB, Kales JD et al. Rebound insomnia. Science. 1980; 208:424. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17843621

32. Bixler EO, Kales JD, Kales A et al. Rebound insomnia and elimination half-life: assessment of individual subject response. J Clin Pharmacol. 1985; 25:115-24. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2859304

33. Gillin JC, Spinweber CL, Johnson LC. Rebound insomnia: a critical review. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1989; 9:161-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2567741

34. Kales A, Kales JD. Sleep laboratory studies of hypnotic drugs: efficacy and withdrawal effects. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1983; 3:140-50. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6132933

35. Kales A, Soldatos CR, Bixler EO et al. Midazolam: dose-response studies of effectiveness and rebound insomnia. Pharmacology. 1983; 26:138-49. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6132414

36. Kales A, Soldatos CR, Bixler EO et al. Rebound insomnia and rebound anxiety: a review. Pharmacology. 1983; 26:121-37. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6132413

37. Kales A, Scharf MB, Kales JD et al. Rebound insomnia: a potential hazard following withdrawal of certain benzodiazepines. JAMA. 1979; 241:1692-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/430730

38. Kales A, Scharf MB, Kales JD. Rebound insomnia: a new clinical syndrome. Science. 1978; 201:1039-41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/684426

39. Kales A, Bixler EO, Kales JD et al. Comparative effectiveness of nine hypnotic drugs: sleep laboratory studies. J Clin Pharmacol. 1977; 17:207-13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/321488

40. Vogel GW, Barker K, Gibbons P et al. A comparison of the effects of flurazepam 30 mg and triazolam 0.5 mg on the sleep of insomniacs. Psychopharmacologia. 1976; 47:81-6.

41. Murphy P, Hindmarch I, Hyland CM. Aspects of short-term use of two benzodiazepine hypnotics in the elderly. Age Ageing. 1982; 11:222-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6129788

42. Ogura C, Nakazawa K, Majima K et al. Residual effects of hypnotics: triazolam, flurazepam, and nitrazepam. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1980; 68:61-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6104840

43. Morgan K, Oswald I. Anxiety caused by a short-life hypnotic. BMJ. 1982; 284:942. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6121606

44. Larson EB, Kukull WA, Buchner D et al. Adverse drug reactions associated with global cognitive impairment in elderly persons. Ann Intern Med. 1987; 107:169-73. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2886086

45. Bixler EO, Kales A, Brubaker BH et al. Adverse reactions to benzodiazepine hypnotics: spontaneous reporting system. Pharmacology. 1987; 35:286-300. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2892212

46. Juhl RP, Daugherty VM, Kroboth PD. Incidence of next-day anterograde amnesia caused by flurazepam hydrochloride and triazolam. Clin Pharm. 1984; 3:622-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6150782

47. Kales A, Bixler EO, Vela-Bueno A et al. Comparison of short and long half-life benzodiazepine hypnotics: triazolam and quazepam. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1986; 40:378-86. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3530586

48. Jerram T. Hypnotics and sedatives. In: Dukes MNG, ed. Meyler’s side effects of drugs. 10th ed. New York: Elsevier; 1984:81-108.

49. Jerram T. Hypnotics and sedatives. In: Dukes MNG, ed. Side effects of drugs. Annual 11. New York: Elsevier; 1987:37-43.

50. Regestein QR, Reich P. Agitation observed during treatment with newer hypnotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 1985; 46:280-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2861195

51. Adam K, Oswald I. Can a rapidly-eliminated hypnotic cause daytime anxiety? Pharmacopsychiatry. 1989; 22:115-9.

52. Kales A, Soldatos CR, Bixler EO et al. Diazepam: effects on sleep and withdrawal phenomena. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1988; 8:340-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3183072

53. Baker Cummins Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Doral (quazepam) prescribing information. Miami, FL; 1990 May.

54. Ankier SI, Goa KL. Quazepam: a preliminary review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy in insomnia. Drugs. 1988; 35:42-62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2894293

55. Baker Cummins Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Doral (quazepam) drug reference. Miami, FL; 1989 Jul.

56. Baker Cummins Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Doral (quazepam) receptor-selective benzodiazepine hypnotic monograph. Miami, FL; 1990 Feb.

57. Rall TW. Hypnotics and sedatives; ethanol: benzodiazepines and management of insomnia. In: Gilman AG, Rall TW, Nies AS et al. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 8th ed. New York: Pergamon Press; 1990:346-58,369-70.

58. Kales A, Bixler EO, Soldatos CR et al. Quazepam and flurazepam: long-term use and extended withdrawal. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1982; 32:781-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7140142

59. Kales A, Scharf MB, Soldatos CR et al. Quazepam, a new benzodiazepine hypnotic: intermediate-term sleep laboratory evaluation. J Clin Pharmacol. 1980; 20:184-92. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6103903

60. Anon. Quazepam: a new hypnotic. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1990; 32:39-40. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1970112

61. Kales A, Bixler EO, Soldatos CR et al. Quazepam and temazepam: effects of short- and intermediate-term use and withdrawal. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1986; 39:345-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2868823

62. Lee A, Lader M. Tolerance and rebound during and after short-term administration of quazepam, triazolam and placebo to healthy human volunteers. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1988; 3:31-47. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2895786

63. Mamelak M, Csima A, Price V. A comparative 25-night sleep laboratory study on the effects of quazepam and triazolam on chronic insomniacs. J Clin Pharmacol. 1984; 24:65-75. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6143767

64. Mamelak M, Csima A, Price V. Effects of quazepam and triazolam on the sleep of chronic insomniacs: a comparative 25-night sleep laboratory study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1985; 8(Suppl 1):S63-73. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3837688

65. Kales A, Scharf MB, Bixler EO et al. Dose-response studies of quazepam. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981; 30:194-200. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6113910

66. Bixler EO, Kales JD, Kales A et al. Rebound insomnia and elimination half-life: assessment of individual subject response. J Clin Pharmacol. 1985; 25:115-24. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2859304

67. Aden GC, Thatcher C. Quazepam in the short-term treatment of insomnia in outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1983; 44:454-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6361006

68. Kales JD, Kales A, Soldatos CR. Quazepam: sleep laboratory studies of effectiveness and withdrawal. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1985; 8(Suppl 1):S55-62.

69. Mendels J, Stern S. Evaluation of the short-term treatment of insomnia in out-patients with 15 milligrams of quazepam. J Int Med Res. 1983; 11:155-61. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6347747

70. Abbott. ProSom prescribing information. North Chicago, IL; 1990 Dec.

71. Abbott. Product information form for American Hospital Formulary Service on ProSom. North Chicago, IL; 1991 May.

72. Scharf MB, Roth PB, Dominguez RA. Estazolam and flurazepam: a multicenter, placebo-controlled comparative study in outpatients with insomnia. J Clin Pharmacol. 1990; 30:461-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1971831

73. Lamphere J, Roehrs T, Zorick F et al. Chronic hypnotic efficacy of estazolam. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1986; 12:687-91. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2875857

74. Dominguez RA, Goldstein BJ, Jacobson AF et al. Comparative efficacy of estazolam, flurazepam, and placebo in outpatients with insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1986; 47:362-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2873132

75. Greenblatt DJ, Miller LG, Shader RI. Neurochemical and pharmacokinetic correlates of the clinical action of benzodiazepine hypnotic drugs. Am J Med. 1990; 88(Suppl 3A):18-24S.

76. Roehrs T. Rebound insomnia: its determinants and significance. Am J Med. 1990; 88(Suppl 3A):39-42S.

77. Greenblatt DJ, Harmatz JS, Zinny MA et al. Effect of gradual withdrawal on the rebound sleep disorder after discontinuation of triazolam. N Engl J Med. 1987; 317:722-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3306380

78. Kales A, Manfredi RL, Vgontzas AN et al. Rebound insomnia after only brief and intermittent use of rapidly eliminated benzodiazepines. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1991; 49:468- 76. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2015735

79. National Institutes of Health. Drugs and insomnia: the use of medications to promote sleep. Consensus Conference. JAMA. 1984; 251:2410-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6142971

80. Fillastre JP, Geffroy-Josse S, Etienne I et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of zolpidem following repeated doses in hemodialyzed uraemic patients. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1993; 7:1-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8458597

81. Bianchetti G, Dubruc C, Thiercelin JF et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of zolpidem an various physiological and pathological conditions. In: Sauvenet JP, Langer SZ, Morselli PL, eds. Imidazopyridines in sleep disorders. New York: Raven Press; 1988:155-63.

82. Hoehns JD, Perry PJ. Zolpidem: a nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic for treatment of insomnia. Clin Pharm. 1993; 12:814-28. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8275648

83. Ansseau M, Pitchot W, Hansenne M et al. Psychotic reactions to zolpidem. Lancet. 1992; 339:809. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1347827

84. Pons G, Francoual C, Guillet P et al. Zolpidem excretion in breast milk. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1989; 37:245-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2612539

85. George CFP. Perspectives on the management of insomnia in patients with chronic respiratory disorders. Sleep. 2000; 23(Suppl 1): S1-31-7.

86. Searle, Skokie, IL: Personal communication.

87. Salva P, Costa J. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of zolpidem. Therapeutic implications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995; 29:142-53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8521677

88. Pichard L, Gillet G, Bonfils C et al. Oxidative metabolism of zolpidem by human liver cytochrome P450S. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995; 23:1253-62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8591727

89. Sanofi-Aventis. Ambien CR (zolpidem tartrate) extended-release tablet prescribing information. Bridgewater, NJ; 2022 Feb. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/fda/fdaDrugXsl.cfm?setid=404c858c-89ac-4c9d-8a96-8702a28e6e76

90. Sanofi-Aventis, New York, NY: Personal communication.

91. Greene D. Dear healthcare professional letter regarding important updated prescribing information for Ambien (zolpidem tartrate) tablets and Ambien CR (zolpidem tartrate) extended-release tablets. Bridgewater, NJ: Sanofi-Aventis US; 2007 Mar.

93. Meda Pharmaceuticals Inc. Edluar (zolpidem tartrate) sublingual tablets prescribing information. Somerset, NJ: 2022 Aug. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/fda/fdaDrugXsl.cfm?setid=a32884d0-85b5-11de-8a39-0800200c9a66

94. Par Pharmaceutical. Zolpidem tartrate sublingual tablets prescribing information. Chestnut Ridge, NY; 2019 Oct. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/fda/fdaDrugXsl.cfm?setid=44b34e58-114b-4774-9fab-4b188dfe0228

95. Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: Risk of next-morning impairment after use of insomnia drugs; FDA requires lower recommended doses for certain drugs containing zolpidem (Ambien, Ambien CR, Edluar, Zolpimist). Rockville, MD; 2013 Jan 10. From FDA website. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm334033.htm

96. Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: FDA approves new label changes and dosing for zolpidem products and a recommendation to avoid driving the day after using Ambien CR. Rockville, MD; 2013 May 14. From FDA website. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm352085.htm

97. Krystal AD, Erman M, Zammit GK et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of zolpidem extended-release 12.5 mg, administered 3 to 7 nights per week for 24 weeks, in patients with chronic primary insomnia: a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter study. Sleep. 2008; 31:79-90. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18220081

98. Roth T, Hull SG, Lankford DA et al. Low-dose sublingual zolpidem tartrate is associated with dose-related improvement in sleep onset and duration in insomnia characterized by middle-of-the-night (MOTN) awakenings. Sleep. 2008; 31:1277-84. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18788653

99. Roth T, Krystal A, Steinberg FJ et al. Novel sublingual low-dose zolpidem tablet reduces latency to sleep onset following spontaneous middle-of-the-night awakening in insomnia in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, outpatient study. Sleep. 2013; 36:189-96. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23372266

100. Zolpidem. In: Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Yaffe SJ. Drugs in pregnancy and lactation: a reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011:1611-3.

101. Villikka K, Kivistö KT, Luurila H et al. Rifampin reduces plasma concentrations and effects of zolpidem. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997; 62:629-34. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9433391

102. Allard S, Sainati S, Roth-Schechter B et al. Minimal interaction between fluoxetine and multiple-dose zolpidem in healthy women. Drug Metab Dispos. 1998; 26:617-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9660843

103. Piergies AA, Sweet J, Johnson M et al. The effect of co-administration of zolpidem with fluoxetine: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996; 34:178-83. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8861737

104. Luurila H, Kivistö KT, Neuvonen PJ. Effect of itraconazole on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of zolpidem. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998; 54:163-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9626922

105. Allard S, Sainati SM, Roth-Schechter BF. Coadministration of short-term zolpidem with sertraline in healthy women. J Clin Pharmacol. 1999; 39:184-91. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11563412

200. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communications: FDA adds Boxed Warning for risk of serious injuries caused by sleepwalking with certain prescription insomnia medicines. Silver Spring, MD; 2019 Apr 30. From FDA website. https://www.fda.gov/media/123819/download

201. Chopra A, Selim B, Silber MH et al. Para-suicidal amnestic behavior associated with chronic zolpidem use: implications for patient safety. Psychosomatics. 2013; 54:498-501. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23352047

202. Gibson CE, Caplan JP. Zolpidem-associated parasomnia with serious self-injury: a shot in the dark. Psychosomatics. 2011; 52:88-91. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21300202

203. Liskow B, Pikalov A. Zaleplon overdose associated with sleepwalking and complex behavior. J Am Acad Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004; 43:927-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15266187

204. Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008; 4:487-504.

205. Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD et al. Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017; 13):307–49 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27998379

206. Qaseem A, Kansagara, D, Forciea MA et al. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016; 165:125-33.

999. By the 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023 Jul;71(7):2052-2081. doi: 10.1111/jgs.18372. Epub 2023 May 4. PMID: 37139824

Related/similar drugs

Frequently asked questions

- What are the strongest sleeping pills?

- Why am I unable to sleep after taking Ambien?

- Quviviq vs. Ambien: How do they compare?

- Is Ambien safe for long-term use?

- Ambien: What are 11 Things You Need to Know?

- Is Ambien a benzo?

- Is Ambien addictive?

- Is “Ambien-Tweeting” or "Sleep-Tweeting" a Thing?

- What is this pill? Tannish peach color, elliptical, marked 10 MG and 5 dots in a small box?

More about zolpidem

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (1,063)

- Drug images

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- Patient tips

- During pregnancy

- Support group

- Drug class: miscellaneous anxiolytics, sedatives and hypnotics

- Breastfeeding

- En español

Patient resources

Professional resources

- Zolpidem prescribing information

- Zolpidem Capsule (FDA)

- Zolpidem Extended Release (FDA)

- Zolpidem Sublingual (FDA)

Other brands

Ambien, Ambien CR, Intermezzo, Edluar, Zolpimist