Ticagrelor (Monograph)

Brand name: Brilinta

Drug class: Platelet-aggregation Inhibitors

Chemical name: (1S,2S,3R,5S)-3-[7-[[(1R,2S)-2-(3,4-Difluorophenyl)cyclopropyl]amino]-5-(propylthio)-3H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-d]pyrimidin-3-yl]-5-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-1,2-cyclopentanediol

Molecular formula: C23H28F2N6O4S

CAS number: 274693-27-5

Warning

- Bleeding

-

Potential risk of bleeding; may be serious, sometimes fatal.1 2 13 41 42 (See Bleeding under Cautions.)

-

Avoid use in patients with active pathologic bleeding or history of intracranial hemorrhage.1 Do not initiate in patients undergoing urgent CABG.1

-

If bleeding occurs, attempt to manage without discontinuing ticagrelor; increased risk of subsequent cardiovascular events possible with premature discontinuance.1 45 (See Discontinuance of Therapy in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease under Cautions.)

Introduction

Platelet-activation and -aggregation inhibitor; nonthienopyridine, reversible, P2Y12 platelet adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-receptor antagonist.1 13 16 18 33 41 42 991 992 994

Uses for Ticagrelor

Acute Coronary Syndrome or History of MI

Used in conjunction with aspirin to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke in patients with ACS.1 2 4 5 8 9 32 33 35 36 60 991 992 994 1005

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with a P2Y12 inhibitor (e.g., clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor) and aspirin is considered the current standard of care in patients with ACS.33 991 992 994 1005

ACC/AHA has issued guidelines for treatment options and duration of DAPT.991 992 994 1005 Aspirin should almost always be continued indefinitely; decisions about specific P2Y12 inhibitor and duration of therapy should be based on risks of bleeding versus benefits of ischemic reduction, clinical judgment, and patient preference.1005

ACC/AHA generally recommends a shorter duration of DAPT for patients at reduced ischemic, but high bleeding, risk and a longer duration for patients at high ischemic, but reduced bleeding, risk.1005

In ACS patients managed medically (without revascularization or reperfusion therapy) or with PCI and stent implantation (bare-metal or drug-eluting), P2Y12 inhibitor therapy should be given for at least 12 months; in patients who have tolerated DAPT without bleeding complications and do not have a high risk of bleeding, continuation of such therapy for longer than 12 months may be reasonable.1005

With regard to the specific P2Y12 inhibitor, evidence supports use of clopidogrel or ticagrelor in medically-managed ACS patients; clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor may be used in ACS patients treated with PCI.991 992 994 1005

In patients undergoing CABG, P2Y12 inhibitor therapy should be resumed after surgery to complete 12 months of therapy.1005

Unlike clopidogrel, genetic polymorphism of the CYP2C19 isoenzyme does not appear to affect the pharmacodynamic or clinical response to ticagrelor.1 The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines recommend ticagrelor as an alternative antiplatelet agent to clopidogrel in patients who are poor or intermediate metabolizers of CYP2C19.1000

When selecting an appropriate antiplatelet regimen, consider individual patient (e.g., ischemic and bleeding risk) and drug-related (e.g., adverse effects, drug interaction potential) factors.13 14 41 43 49

Also used to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke in patients with a history of MI; in the principal study establishing efficacy for this indication, patients had a history of MI 1–3 years prior to study entry.31 60

AHA/ACC states that in patients with stable ischemic heart disease (SIHD) being treated with DAPT for previous (1–3 years prior) MI, continuation of such therapy may be reasonable if tolerated without any bleeding complications.1005

Coronary Artery Disease but No Prior Stroke or MI

Used to reduce the risk of an initial MI or stroke in patients with established CAD who are at high risk for these thrombotic cardiovascular events.1 62

Use in conjunction with aspirin therapy.1

There is evidence supporting use of ticagrelor in reducing risk of a first MI and stroke in patients with CAD and type 2 diabetes mellitus, although treatment effect is small.32 62 Reduction in ischemic events is accompanied by increased risk of bleeding.1 62

Acute Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack

Used to reduce the risk of stroke in patients with acute ischemic stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] ≤5) or high-risk TIA.1 63

Use in conjunction with aspirin therapy.1

Not studied in patients with more severe stroke or cardioembolic stroke; those undergoing thrombectomy or thrombolysis; and those in whom treatment was administered >24 hours after symptom onset.63

Ticagrelor Dosage and Administration

Administration

Administer orally without regard to meals.1 48

For patients unable to swallow tablets whole, may crush and mix with water.1 Also can administer crushed tablet in water mixture via a nasogastric tube (CH8 or greater).1

If a dose is missed, take next dose at the regularly scheduled time.1

Dosage

Adults

Acute Coronary Syndrome or History of MI

Oral

180-mg loading dose followed by maintenance dosage of 90 mg twice daily during the first year.1 35 36 After first year, maintenance dosage of 60 mg twice daily recommended.1

Adjunctive aspirin therapy: Administer maintenance dosage of 75–100 mg daily.1 (See Reduced Response with Higher Aspirin Dosages in Patients with ACS under Cautions.)

Manufacturer makes no specific recommendation regarding duration of maintenance therapy; however, ticagrelor was administered for up to 12 months in the pivotal efficacy study (PLATO).1 2 13 Recommendations for duration of dual antiplatelet therapy can be found in ACC/AHA guidelines.1005 (See Acute Coronary Syndrome or History of MI under Uses.)

Coronary Artery Disease but No Prior Stroke or MI

Oral

60 mg twice daily.1

Adjunctive aspirin therapy: Administer maintenance dosage of 75–100 mg daily.1

Acute Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack

Oral

180-mg loading dose followed by maintenance dosage of 90 mg twice daily for up to 30 days.1

Adjunctive aspirin therapy: After initial loading dose (300–325 mg), administer maintenance dosage of 75–100 mg daily.1

Transitioning from Clopidogrel to Ticagrelor Therapy

Oral

May transition patients directly from clopidogrel to ticagrelor therapy without interruption in antiplatelet effects.1 26 In clinical trials, patients who switched from clopidogrel to ticagrelor received an initial loading dose of ticagrelor regardless of whether a previous loading dose of clopidogrel had been given.2 26

Special Populations

Renal Impairment

No dosage adjustment required in patients with renal impairment.1 31

Hepatic Impairment

No dosage adjustment required in patients with mild hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class A).1 29 (See Hepatic Impairment under Cautions.)

Geriatric Patients

Dosage adjustment based on age not required.1

Cautions for Ticagrelor

Contraindications

-

History of intracranial hemorrhage.1

-

Active pathologic bleeding (e.g., peptic ulcer, intracranial hemorrhage).1

-

Hypersensitivity to the drug or any components.1

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Bleeding

Risk of bleeding, including serious, sometimes fatal bleeding.1 2 13 41 42 50 (See Boxed Warning.)

Overall risk of major and minor bleeding somewhat greater with ticagrelor than with clopidogrel in the PLATO trial.1 4 9 42 Increased risk principally involved non-CABG-related major bleeding, including fatal intracranial hemorrhage.1 2 4 6 8 9 13 41 994 Rates of major CABG-related bleeding were similar between ticagrelor and clopidogrel.1 2 4 5 16

Bleeding was reported more frequently with ticagrelor compared with placebo in other preapproval studies.1 60 62 63

In general, risk factors for bleeding include advanced age, history of bleeding disorders, female gender, renal dysfunction, performance of PCI, and concurrent use of other drugs that affect hemostasis (e.g., anticoagulants, thrombolytic agents, high dosages of aspirin, long-term use of NSAIAs).65

Contraindicated in patients who are actively bleeding or who have a history of intracranial hemorrhage.1 Also not recommended in patients likely to undergo urgent CABG.1 Temporarily discontinue drug at least 5 days prior to surgery (e.g., CABG) whenever possible.1 70

If possible, manage bleeding without discontinuing ticagrelor; premature discontinuance may increase risk of subsequent cardiovascular events.1 (See Discontinuance of Therapy in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease under Cautions.)

Reduced Response with Higher Aspirin Dosages in Patients with ACS

In the PLATO study, a reduced response to ticagrelor was observed when used with aspirin maintenance dosages >100 mg daily in patients with ACS.1 15 16 Avoid aspirin dosages >100 mg daily.1 (See Boxed Warning.)

Other Warnings and Precautions

Dyspnea

Risk of dyspnea,1 2 4 8 13 16 20 22 24 26 30 36 generally mild to moderate and self-limiting.1 2 20 22 Adverse effects on pulmonary function not observed.1 16 22 Mechanism of dyspnea unknown, but thought to be related to an adenosine-mediated response.13 16 20 22

If any new, prolonged, or worsening dyspnea related to ticagrelor occurs, no specific treatment required; may continue therapy without interruption if possible.1 If dyspnea is intolerable and results in discontinuance of ticagrelor, consider another antiplatelet agent.1

Discontinuance of Therapy in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease

In general, avoid premature discontinuance of antiplatelet therapy (e.g., P2Y12-receptor antagonists, aspirin) in patients with CAD because of subsequent increased risk of ischemic complications.1 45 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 Stent thrombosis, MI, and/or death observed in patients with coronary stents who prematurely discontinued antiplatelet therapy.45 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57

If temporary discontinuance of ticagrelor required (e.g., prior to significant surgery or for bleeding), reinstitute therapy as soon as possible.1 45 Interrupt therapy for 5 days prior to surgical procedures with a major bleeding risk if possible; resume therapy when hemostasis is achieved.1

Bradyarrhythmias

Ventricular pauses ≥3 seconds, usually occurring during first week of therapy, reported.1 2 16 21 30 36 Mostly asymptomatic and not associated with any clinically important effects (e.g., syncope, need for pacemaker insertion).1 2 21

Because patients with baseline increased risk of bradycardia (e.g., those with sick sinus syndrome, second- or third-degree AV block, or syncope due to bradycardia without a pacemaker) were excluded from clinical studies,1 some clinicians recommend caution when used in such patients.21

Laboratory Test Interference

May cause false negative results in platelet function tests for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (e.g., heparin-induced platelet aggregation [HIPA] assay).1 However, not expected to affect PF4 antibody testing for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.1

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

No drug-associated risk of major birth defects, miscarriage, or adverse maternal or fetal outcomes identified.1

Lactation

Distributed into milk in rats; not known whether distributed into human milk.1 Breast-feeding not recommended during ticagrelor therapy.1

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy not established in pediatric patients.1 2

Geriatric Use

No overall differences in efficacy or safety between geriatric and younger patients.1

Ticagrelor pharmacokinetics not substantially affected by age.1 27

Hepatic Impairment

Possible increased exposure and risk of bleeding.1 (See Absorption: Special Populations under Pharmacokinetics.)

Avoid use in patients with severe hepatic impairment.1 Carefully consider use in those with moderate hepatic impairment after weighing risks versus benefits.1 May be used in patients with mild hepatic impairment without dosage adjustment.1 29

Renal Impairment

Pharmacokinetics and clinical efficacy not substantially altered in patients with renal impairment.1 24 31 (See Renal Impairment under Dosage and Administration.)

Not studied in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on dialysis; however, clinically important differences not expected in such patients receiving intermittent hemodialysis.1

Ticagrelor is not dialyzable.1

Common Adverse Effects

Bleeding, dyspnea.1

Drug Interactions

Metabolized principally by CYP isoenzyme 3A4.1 Weak inhibitor of CYP3A4/5 and potential activator of CYP3A5.1 Does not inhibit CYP 1A2, 2C19, or 2E1.1

P-glycoprotein substrate and inhibitor.1

Drugs Affecting Hemostasis

Possible increased risk of bleeding.1 (See Bleeding under Cautions and see Specific Drugs under Interactions.)

Drugs Affecting or Metabolized by Hepatic Microsomal Enzymes

Potent CYP3A inhibitors: Potential pharmacokinetic interaction (substantially increased exposure to ticagrelor); possible increased risk of bleeding.1 36 Avoid concomitant use.1

Moderate CYP3A inhibitors: Possible increased ticagrelor exposure; dosage adjustment not necessary.1

Potent CYP3A inducers: Potential pharmacokinetic interaction (substantially decreased plasma ticagrelor concentrations); possible reduced efficacy.1 36 Avoid concomitant use.1

CYP3A substrates: Potential pharmacokinetic interaction (increased plasma concentrations of substrate drug).1 36

Drugs Affecting or Affected by P-glycoprotein Transport

P-glycoprotein substrates: Potential pharmacokinetic interaction (increased plasma concentrations of substrate drug).1 36

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Anticoagulants |

Possible increased risk of bleeding1 |

|

|

Anticonvulsants (carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin) |

Substantially reduced plasma ticagrelor concentrations due to CYP3A induction1 |

Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

Antifungals, azole (itraconazole, ketoconazole, voriconazole) |

Substantially increased exposure to ticagrelor due to potent CYP3A inhibition1 |

Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

Aspirin |

Possible reduced efficacy of ticagrelor when used with aspirin dosages >100 mg daily1 15 16 Increased risk of bleeding possible with high dosages of aspirin1 Pharmacokinetics of ticagrelor not altered1 |

Limit concomitant aspirin maintenance dosage to 75–100 mg daily1 |

|

Atazanavir |

Substantially increased exposure to ticagrelor due to potent CYP3A inhibition1 |

Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

Clarithromycin |

Substantially increased exposure to ticagrelor due to potent CYP3A inhibition1 |

Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

Cyclosporine |

Possible increased exposure to ticagrelor1 |

|

|

Desmopressin |

Pharmacokinetics of ticagrelor not affected1 |

No dosage adjustment necessary1 |

|

Digoxin |

Pharmacokinetics of digoxin not substantially altered1 |

No dosage adjustment necessary; monitor serum digoxin concentrations prior to and following any change in ticagrelor therapy1 |

|

Diltiazem |

Possible decreased exposure to ticagrelor due to moderate CYP3A inhibition1 |

No dosage adjustment necessary1 |

|

Enoxaparin |

Pharmacokinetics of ticagrelor not affected1 Possible increased risk of bleeding1 |

No dosage adjustment necessary1 |

|

Heparin |

Pharmacokinetics of ticagrelor not affected1 Possible increased risk of bleeding1 |

No dosage adjustment necessary1 |

|

HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) |

Lovastatin, simvastatin: Possible increased serum concentrations of the statin1 Atorvastatin: Pharmacokinetics of atorvastatin not substantially altered1 |

Lovastatin, simvastatin: Do not exceed dosage of 40 mg daily1 Atorvastatin: No dosage adjustment necessary1 |

|

Hormonal contraceptives (ethinyl estradiol/levonorgestrel) |

Increased peak plasma concentrations of and systemic exposure to ethinyl estradiol; pharmacokinetics of levonorgestrel not altered 1 46 Ticagrelor not expected to affect contraceptive efficacy42 46 |

No dosage adjustment necessary1 |

|

Nefazodone |

Substantially increased exposure to ticagrelor due to potent CYP3A inhibition1 |

Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

Nelfinavir |

Substantially increased exposure to ticagrelor due to potent CYP3A inhibition1 |

Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

NSAIAs |

Possible increased risk of bleeding with chronic NSAIA use1 |

|

|

Opiate agonists (e.g., morphine) |

May delay and reduce absorption of ticagrelor and its active metabolite1 Ticagrelor exposure was decreased and time to peak plasma concentration was delayed when coadministered with IV fentanyl or IV morphine; platelet aggregation was higher up to 3 hours post-loading dose in ACS patients who received these drugs concomitantly1 |

Consider use of a parenteral antiplatelet agent in ACS patients who require treatment with morphine or other opiate agonist1 |

|

Proton-pump inhibitors |

Platelet response to ticagrelor not affected7 |

|

|

Rifampin |

Substantially decreased peak plasma concentrations of and systemic exposure to ticagrelor due to potent CYP3A induction1 |

Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

Ritonavir |

Substantially increased exposure to ticagrelor due to potent CYP3A inhibition1 |

Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

Saquinavir |

Substantially increased exposure to ticagrelor due to potent CYP3A inhibition1 |

Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

Thrombolytics |

Possible increased risk of bleeding1 |

|

|

Tolbutamide |

Pharmacokinetics of tolbutamide not substantially altered1 |

Dosage adjustment not necessary1 |

Ticagrelor Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Rapidly but incompletely absorbed after oral administration;13 25 27 28 29 mean absolute oral bioavailability about 36%.1

Plasma concentrations of ticagrelor and its major metabolite increase in a dose-dependent manner; peak concentrations achieved within approximately 1.5 and 2.5 hours, respectively.1 18 25 27 28 29

Onset

Maximum inhibition of platelet aggregation observed approximately 2 hours after a dose.1 19 25 26 27 28

Additional inhibition of platelet aggregation (absolute increase of 26.4%) observed in patients who transition from clopidogrel to ticagrelor therapy.1 26

Duration

Maximum inhibition of platelet aggregation maintained for ≥8 hours after a dose.1 Following discontinuance, platelet activity returns to baseline after 5 days.1 19

Food

High-fat meal increased systemic exposure to ticagrelor by 21% and decreased peak plasma concentrations of the active metabolite by 22%; no effect on plasma concentrations of ticagrelor or systemic exposure to active metabolite.1 48

Special Populations

Individuals with mild (Child-Pugh class A) hepatic impairment had slightly higher systemic exposure to ticagrelor than those with normal hepatic function; however, no clinically important effects observed.1 29

Individuals with severe (Clcr <30 mL/minute) renal impairment had slightly higher systemic exposure to ticagrelor than those with normal renal function; however, no effect on platelet inhibition or tolerability.31

Distribution

Plasma Protein Binding

>99% for both ticagrelor and active metabolite.1

Elimination

Metabolism

Metabolized principally by CYP3A4 to active metabolite.1 13 27

Elimination Route

Primarily eliminated in feces; <1% of a dose is recovered in urine (as parent drug and active metabolite).1 13

Half-life

Ticagrelor: Approximately 7 hours.1 25 28

Active metabolite: Approximately 9 hours.1 25 28

Stability

Storage

Oral

Tablets

25°C (may be exposed to 15–30°C).1

Actions

-

Nonthienopyridine P2Y12 platelet ADP-receptor antagonist; unlike thienopyridines (e.g., clopidogrel, prasugrel), ticagrelor binds reversibly to P2Y12 receptor and does not require hepatic transformation to exerts its pharmacologic effect.1 2 3 7 13 16 18 25 27 41 42

-

Prevents signal transduction of the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) pathway, resulting in reduced exposure of fibrinogen binding sites to the platelet glycoprotein (GP IIb/IIIa) complex and subsequent inhibition of platelet activation and aggregation.1 13

-

Inhibits reuptake of adenosine into erythrocytes.10 11 12 13 14 16

-

Compared with clopidogrel, ticagrelor produces more rapid and effective inhibition of platelet aggregation and has a faster offset of action.1 2 7 18 19 26 27 28 30 36 However, relationship between inhibition of platelet aggregation and clinical outcomes of either drug not known.1

-

Pharmacogenomics: Genetic polymorphism of the CYP2C19 isoenzyme does not appear to affect pharmacodynamic or clinical response to ticagrelor.1 23 41 47

Advice to Patients

-

Importance of patients reading the FDA-approved patient labeling (medication guide).1

-

Importance of patients informing clinicians (e.g., physicians, dentists) about ticagrelor therapy before any surgery or dental procedure is performed.1 45

-

Importance of informing patients not to take aspirin dosages exceeding 100 mg daily; advise patients to not take any other aspirin-containing drugs.1

-

Importance of informing patients that they will bruise and/or bleed more easily and that a longer than usual time will be required to stop bleeding when taking ticagrelor.1 Importance of patients informing clinicians about any unexpected, prolonged, or excessive bleeding, or blood in urine or stool.1

-

Importance of informing patients that ticagrelor can cause dyspnea; advise patient to contact their clinician if they experience any unexpected shortness of breath.1

-

Importance of informing clinicians of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs, particularly drugs that affect bleeding risk (e.g., heparin, warfarin).1

-

Importance of women informing clinicians if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1

-

Importance of informing patients of other important precautionary information.1 (See Cautions.)

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

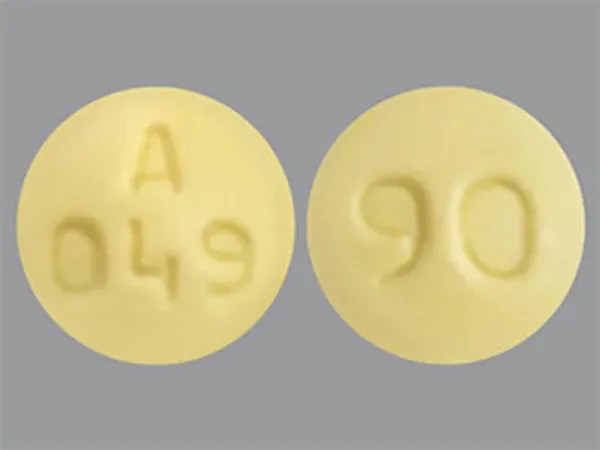

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Tablets, film-coated |

60 mg |

Brilinta |

AstraZeneca |

|

90 mg* |

Brilinta |

AstraZeneca |

||

|

Ticagrelor Tablets |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions October 4, 2021. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

References

1. AstraZeneca. Brilinta, (ticagrelor) tablets prescribing information. Wilmington, DE; 2021 Feb.

2. Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:1045-57. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19717846

3. James S, Akerblom A, Cannon CP et al. Comparison of ticagrelor, the first reversible oral P2Y(12) receptor antagonist, with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes: Rationale, design, and baseline characteristics of the PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Am Heart J. 2009; 157:599-605. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19332184

4. Steg PG, James S, Harrington RA et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes intended for reperfusion with primary percutaneous coronary intervention: A Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial subgroup analysis. Circulation. 2010; 122:2131-41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21060072

5. Held C, Asenblad N, Bassand JP et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery: results from the PLATO (Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 57:672-84. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21194870

6. Becker RC, Bassand JP, Budaj A et al. Bleeding complications with the P2Y12 receptor antagonists clopidogrel and ticagrelor in the PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Eur Heart J. 2011; 32:2933-44. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22090660

7. Storey RF, Angiolillo DJ, Patil SB et al. Inhibitory effects of ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel on platelet function in patients with acute coronary syndromes: the PLATO (PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes) PLATELET substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 56:1456-62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20832963

8. Cannon CP, Harrington RA, James S et al. Comparison of ticagrelor with clopidogrel in patients with a planned invasive strategy for acute coronary syndromes (PLATO): a randomised double-blind study. Lancet. 2010; 375:283-93. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20079528

9. James SK, Roe MT, Cannon CP et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes intended for non-invasive management: substudy from prospective randomised PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. BMJ. 2011; 342:d3527. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3117310/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21685437

10. Schneider DJ. Mechanisms potentially contributing to the reduction in mortality associated with ticagrelor therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 57:685-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21194871

11. Serebruany VL. Adenosine release: a potential explanation for the benefits of ticagrelor in the PLATelet inhibition and clinical outcomes trial?. Am Heart J. 2011; 161:1-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21167333

12. Serebruany VL, Atar D. The PLATO trial: do you believe in magic?. Eur Heart J. 2010; 31:764-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20007979

13. Anderson SD, Shah NK, Yim J et al. Efficacy and safety of ticagrelor: a reversible P2Y12 receptor antagonist. Ann Pharmacother. 2010; 44:524-37. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20124464

14. Tapp L, Shantsila E, Lip GY. Role of ticagrelor in clopidogrel nonresponders: resistance is futile?. Circulation. 2010; 121:1169-71. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20194888

15. Mahaffey KW, Wojdyla DM, Carroll K et al. Ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel by geographic region in the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Circulation. 2011; 124:544-54. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21709065

16. Gaglia MA, Waksman R. Overview of the 2010 Food and Drug Administration Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee meeting regarding ticagrelor. Circulation. 2011; 123:451-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21242480

17. Schömig A. Ticagrelor--is there need for a new player in the antiplatelet-therapy field?. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361:1108-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19717845

18. Storey RF, Husted S, Harrington RA et al. Inhibition of platelet aggregation by AZD6140, a reversible oral P2Y12 receptor antagonist, compared with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 50:1852-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17980251

19. Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Butler K et al. Randomized double-blind assessment of the ONSET and OFFSET of the antiplatelet effects of ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with stable coronary artery disease: the ONSET/OFFSET study. Circulation. 2009; 120:2577-85. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19923168

20. Storey RF, Becker RC, Harrington RA et al. Characterization of dyspnoea in PLATO study patients treated with ticagrelor or clopidogrel and its association with clinical outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2011; 32:2945-53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21804104

21. Scirica BM, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H et al. The incidence of bradyarrhythmias and clinical bradyarrhythmic events in patients with acute coronary syndromes treated with ticagrelor or clopidogrel in the PLATO (Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes) trial: results of the continuous electrocardiographic assessment substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 57:1908-16. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21545948

22. Storey RF, Bliden KP, Patil SB et al. Incidence of dyspnea and assessment of cardiac and pulmonary function in patients with stable coronary artery disease receiving ticagrelor, clopidogrel, or placebo in the ONSET/OFFSET study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 56:185-93. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20620737

23. Wallentin L, James S, Storey RF et al. Effect of CYP2C19 and ABCB1 single nucleotide polymorphisms on outcomes of treatment with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel for acute coronary syndromes: a genetic substudy of the PLATO trial. Lancet. 2010; 376:1320-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20801498

24. James S, Budaj A, Aylward P et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in acute coronary syndromes in relation to renal function: results from the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Circulation. 2010; 122:1056-67. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20805430

25. Teng R, Butler K. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, tolerability and safety of single ascending doses of ticagrelor, a reversibly binding oral P2Y(12) receptor antagonist, in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010; 66:487-96. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20091161

26. Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Butler K et al. Response to ticagrelor in clopidogrel nonresponders and responders and effect of switching therapies: the RESPOND study. Circulation. 2010; 121:1188-99. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20194878

27. Husted S, Emanuelsson H, Heptinstall S et al. Pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and safety of the oral reversible P2Y12 antagonist AZD6140 with aspirin in patients with atherosclerosis: a double-blind comparison to clopidogrel with aspirin. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27:1038-47. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16476694

28. Butler K, Teng R. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety and tolerability of multiple ascending doses of ticagrelor in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010; 70:65-77. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2909809/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20642549

29. Butler K, Teng R. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of ticagrelor in volunteers with mild hepatic impairment. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011; 51:978-87. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20926753

30. Cannon CP, Husted S, Harrington RA et al. Safety, tolerability, and initial efficacy of AZD6140, the first reversible oral adenosine diphosphate receptor antagonist, compared with clopidogrel, in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: primary results of the DISPERSE-2 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 50:1844-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17980250

31. Bonaca MP, Bhatt DL, Steg PG et al. Ischaemic risk and efficacy of ticagrelor in relation to time from P2Y12 inhibitor withdrawal in patients with prior myocardial infarction: insights from PEGASUS-TIMI 54. Eur Heart J. 2016; 37:1133-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26491109

32. US Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research: Application number 022433Orig1s028: Summary review. 2018 Jun 22. From FDA website https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2020/022433Orig1s028.pdf

33. Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2021; 42:1289-1367. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32860058

35. Anon. Antithrombotic drugs. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2014;56: 103-109.

36. Ticagrelor (Brilinta)-better than clopidogrel? Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2011; 53: 69-70.

37. Serebruany VL. Viewpoint: paradoxical excess mortality in the PLATO trial should be independently verified. Thromb Haemost. 2011; 105:752-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21384079

38. Wallentin L, Becker RC, James SK et al. The PLATO trial reveals further opportunities to improve outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Editorial on Serebruany. “Viewpoint: Paradoxical excess mortality in the PLATO trial should be independently verified” (Thromb Haemost 2011; 105.5). Thromb Haemost. 2011; 105:760-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21394383

39. Ohman EM, Roe MT. Explaining the unexpected: insights from the PLATelet inhibition and clinical Outcomes (PLATO) trial comparing ticagrelor and clopidogrel. Editorial on Serebruany “Viewpoint: Paradoxical excess mortality in the PLATO trial should be independently verified” (Thromb Haemost 2011; 105.5). Thromb Haemost. 2011; 105:763-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21394382

40. Storey RF, Becker RC, Harrington RA et al. Pulmonary function in patients with acute coronary syndrome treated with ticagrelor or clopidogrel (from the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes [PLATO] pulmonary function substudy). Circulation. 2011; 124:2610-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22064600

41. Oh EY, Abraham T, Saad N et al. A comprehensive comparative review of adenosine diphosphate receptor antagonists. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012; 13:175-91. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22216937

42. Deeks ED. Ticagrelor: a review of its use in the management of acute coronary syndromes. Drugs. 2011; 71:909-33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21568367

43. Crouch MA, Colucci VJ, Howard PA et al. P2Y12 receptor inhibitors: integrating ticagrelor into the management of acute coronary syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2011; 45:1151-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21852599

45. Grines CL, Bonow RO, Casey DE et al. Prevention of premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery stenosis. A science advisory from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, American College of Surgeons, and American Dental Association, with representation from the American College of Physicians. JADA. 2007; 138:652-5.

46. Butler K, Teng R. Effect of ticagrelor on the pharmacokinetics of ethinyl oestradiol and levonorgestrel in healthy volunteers. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011; 27:1585-93. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21692601

47. Tantry US, Bliden KP, Wei C et al. First analysis of the relation between CYP2C19 genotype and pharmacodynamics in patients treated with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel: the ONSET/OFFSET and RESPOND genotype studies. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010; 3:556-66. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21079055

48. Teng R, Mitchell PD, Butler K. Lack of significant food effect on the pharmacokinetics of ticagrelor in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011; :. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3144980/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21967645

49. Spinler SA. Oral antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome and percutaneous coronary intervention: balancing efficacy and bleeding risk. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010; 67(15 Suppl 7):S7-17. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3096563/

50. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Mehta SR et al. Ticagrelor in patients with diabetes and stable coronary artery disease with a history of previous percutaneous coronary intervention (THEMIS-PCI): a phase 3, placebo-controlled, randomised trial. Lancet. 2019; 394:1169-1180. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31484629

51. Ong ATL, McFadden EP, Regar E et al. Late angiographic stent thrombosis (LAST) events with drug-eluting stents. JACC. 2005; 45:2088-92. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15963413

52. Jeremias A, Sylvia B, Bridges J et al. Stent thrombosis after successful sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Circulation. 2004 109:1930-2.

53. Pfisterer M, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Buser PT et al. Late clinical events after clopidogrel discontinuation may limit the benefit of drug-eluting stents. JACC. 2006; 48:2584-91. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17174201

54. Luscher TF, Steffel J, Eberli FR et al. Drug-eluting stent and coronary thrombosis. Biological mechanisms and clinical implications. Circulation. 2007; 115:1051-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17325255

55. Eisenstein EL, Anstrom KJ, Kong DF et al. Clopidogrel use and long-term clinical outcomes after drug-eluting stent implantation. JAMA. 2007;297:159-168.

56. Kereiakes DJ. Does clopidogrel each day keep stent thrombosis away? JAMA. 2007; 297:209-11. Editorial.

57. Spertus JA, Kettelkamp R, Vance C et al. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of premature discontinuation of thienopyridine therapy after drug-eluting stent placement. Results from the PREMIER registry. Circulation. 2006; 113:2803-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16769908

58. Amarenco P, Denison H, Evans SR et al. Ticagrelor Added to Aspirin in Acute Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack in Prevention of Disabling Stroke: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2020; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMCPMC7648910/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33159526

60. Bonaca MP, Bhatt DL, Cohen M et al. Long-term use of ticagrelor in patients with prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:1791-800. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25773268

61. Schüpke S, Neumann FJ, Menichelli M et al. Ticagrelor or Prasugrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:1524-1534. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31475799

62. Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Simon T et al. Ticagrelor in Patients with Stable Coronary Disease and Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:1309-1320. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31475798

63. Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Denison H et al. Ticagrelor and Aspirin or Aspirin Alone in Acute Ischemic Stroke or TIA. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383:207-217. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32668111

64. American College of Cardiology. For CAD, what is the recommended dose of aspirin and why? 2016 Mar 29. From the ACC website. Accessed 2021 May 20. https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2016/03/29/10/08/for-cad-what-is-the-recommended-dose-of-aspirin-and-why

65. Abu-Assi E, Raposeiras-Roubín S, García-Acuña JM et al. Bleeding risk stratification in an era of aggressive management of acute coronary syndromes. World J Cardiol. 2014; 6:1140-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMCPMC4244611/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25429326

70. Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012; 143:4-34. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22172748

991. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014; 130:e344-426. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25249585

992. O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013; 127:e362-425. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23247304

993. Cannon CP, Bhatt DL, Oldgren J et al. Dual Antithrombotic Therapy with Dabigatran after PCI in Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:1513-1524. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28844193

994. Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 58:e44-122. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22070834

1000. Scott SA, Sangkuhl K, Stein CM et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for CYP2C19 genotype and clopidogrel therapy: 2013 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013; 94:317-23. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMCPMC3748366/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23698643

1005. Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA et al. 2016 ACC/AHA Guideline Focused Update on Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines: An Update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery, 2012 ACC/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Stable Ischemic Heart Disease, 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction, 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes, and 2014 ACC/AHA Guideline on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Management of Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery. Circulation. 2016; 134:e123-55. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27026020

1006. Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Yeh RW et al. Twelve or 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med. 2014; 371:2155-66. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMCPMC4481318/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25399658

1014. January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in Collaboration With the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2019; 140:e125-e151. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30686041

1015. Kumbhani DJ, Cannon CP, Beavers CJ et al. 2020 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway for Anticoagulant and Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation or Venous Thromboembolism Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention or With Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021; 77:629-658. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33250267

1016. Jackson LR 2nd, Ju C, Zettler M et al. Outcomes of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Receiving an Oral Anticoagulant and Dual Antiplatelet Therapy: A Comparison of Clopidogrel Versus Prasugrel From the TRANSLATE-ACS Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015; 8:1880-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26718518

1017. Sarafoff N, Martischnig A, Wealer J et al. Triple therapy with aspirin, prasugrel, and vitamin K antagonists in patients with drug-eluting stent implantation and an indication for oral anticoagulation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61:2060-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23524219

1018. Rubboli A, Schlitt A, Kiviniemi T et al. One-year outcome of patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing coronary artery stenting: an analysis of the AFCAS registry. Clin Cardiol. 2014; 37:357-64. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMCPMC6649398/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24481953

1019. Braun OÖ, Bico B, Chaudhry U et al. Concomitant use of warfarin and ticagrelor as an alternative to triple antithrombotic therapy after an acute coronary syndrome. Thromb Res. 2015; 135:26-30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25467434

1020. Lamberts M, Gislason GH, Olesen JB et al. Oral anticoagulation and antiplatelets in atrial fibrillation patients after myocardial infarction and coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 62:981-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23747760

1021. Dewilde WJ, Oirbans T, Verheugt FW et al. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2013; 381:1107-15. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23415013

Related/similar drugs

Frequently asked questions

- How long do I take Brilinta after a stent or heart attack?

- What pain medication can I take with Brilinta?

- How long should Brilinta be held/stopped before surgery?

- Brilinta vs Plavix: what's the difference?

- Is there a generic for Brilinta?

- Is ticagrelor better than clopidogrel?

- What is Brilinta (ticagrelor) used for?

- Is ticagrelor a prodrug?

More about ticagrelor

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (117)

- Drug images

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- Patient tips

- During pregnancy

- Support group

- Drug class: platelet aggregation inhibitors

- Breastfeeding

- En español