Cimetidine, Cimetidine Hydrochloride (Monograph)

Drug class: Histamine H2-Antagonists

Introduction

Histamine H2 receptor antagonist.b

Uses for Cimetidine, Cimetidine Hydrochloride

Duodenal Ulcer

Short-term treatment of active duodenal ulcer (endoscopically or radiographically confirmed).a b

Maintainence of healing and reduction in recurrence of duodenal ulcer.a b

Pathologic GI Hypersecretory Conditions

Long-term treatment of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, multiple endocrine adenomas, systemic mastocytosis.a b

Gastric Ulcer

Short-term treatment of active benign gastric ulcer.a b

Gastroesophageal Reflux (GERD)

Short-term treatment of erosive esophagitis (endoscopically diagnosed) in patients with GERD.118

Treatment of symptomatic GERD† [off-label].105 106 123 288

Self-medication as initial therapy to achieve acid suppression, control symptoms, and prevent complications of less severe symptomatic GERD† [off-label].288

Upper GI Bleeding

Prevention of upper GI bleeding resulting from stress-related mucosal damage (erosive esophagitis, stress ulcers) in critically ill patients.118 142 143 144 145 146 147 152 153 154 155 156 157 161 162 163 164 165 166 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177 179 188 191

Treatment of upper GI bleeding† [off-label] secondary to hepatic failure, esophagitis, duodenal or gastric ulcers when hemorrhage is not caused by major blood vessel erosion.b

Heartburn (pyrosis), Acid Indigestion (hyperchlorhydria), or Sour Stomach

Short-term self-medication for relief of heartburn symptoms in adults and adolescents≥12 years of age.c

Short-term self-medication for prevention of heartburn symptoms associated with acid indigestion (hyperchlorhydria) and sour stomach brought on by ingestion of certain foods and beverages in adults and children ≥12 years of age.c

Cimetidine, Cimetidine Hydrochloride Dosage and Administration

Administration

Administer orally, IV, or IM.118

Administer by IM or slow IV injection, or by intermittent or continuous IV infusion in hospitalized patients with pathological GI hypersecretory conditions or intractable duodenal ulcer, or when oral therapy is not feasible.118

Oral Administration

Administer with or without food; administration with food may delay and slightly decrease absorption, but achieves maximum antisecretory effect when stomach is no longer protected by food buffering effect. Administer oral tablets with water.b

Antacids may be given as necessary for pain relief, but not at the same time.a b

For duodenal ulcer treatment, administration once daily at bedtime is the regimen of choice because of a high healing rate, maximal pain relief, decreased drug interaction potential, and maximal compliance.117 118 119

For gastric ulcer treatment, administration once daily at bedtime is the regimen of choice because of convenience and decreased drug interaction potential.118

For gastroesophageal reflux, once-daily dosing is not considered appropriate.288

IM Administration

May be administered undiluted.a b

Intermittent Direct IV Injection

Dilution

Dilute 300 mg to 20 mL with 0.9% sodium chloride injection or other compatible IV solution before direct IV injection.118

Rate of Administration

Inject over ≥5 minutes.118

Intermittent IV infusion

Reconstitution

Reconstitute ADD-Vantage vials according to manufacturer’s directions.118

Dilution

Dilute 300 mg in at least 50 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride injection or 5% dextrose injection or other compatible IV solution.118

No additional dilution required for commercially available infusion solution (300 mg cimetidine in 50 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride injection).a

Rate of Administration

Over 15–20 minutes.118

Continuous IV Infusion

Dilution

Dilute 900 mg in 100–1000 mL of a compatible IV solution.a b

Rate of Administration

Adjust rate to individual patient requirements.a b

Volume <250 mL: use controlled-infusion device (e.g., pump).a b

Dosage

Dosage of cimetidine hydrochloride expressed in terms of cimetidine.118

Pediatric Patients

20–40 mg/kg daily in divided doses has been used in a limited number of children when potential benefits are thought to outweigh the possible risks.118

Heartburn, Acid Indigestion, or Sour Stomach

Heartburn Relief (Self-medication)

OralAdolescents ≥12 years of age: 200 mg once or twice daily, or as directed by a clinician.268

Prevention of Heartburn (Self-medication)

OralAdolescents ≥12 years of age: 200 mg once or twice daily or as directed by a clinician; administer immediately (or up to 30 minutes) before ingestion of causative food or beverage.c

Adults

General Parenteral Dosage

Parenteral dosage regimens for GERD have not been established.a

General parenteral dosage (in hospitalized patients with pathologic hypersecretory conditions or intractable ulcer, or for short-term use when oral therapy is not feasible):a

IM

300 mg every 6–8 hours.118

Intermittent Direct IV Injection

300 mg every 6–8 hours.118

300 mg more frequently if increased daily dosage is necessary (i.e., single doses not >300 mg), up to 2400 mg daily.118

Intermittent IV Infusion

300 mg every 6–8 hours.118

300 mg more frequently if increased daily dosage is necessary (i.e., single doses not >300 mg), up to 2400 mg daily.118

Continuous IV infusion

900 mg over 24 hours (37.5 mg/hour).a b

For more rapid increase in gastric pH, a loading dose of 150 mg may be given as an intermittent infusion before continuous infusion.a b

Duodenal Ulcer

Treatment of Active Duodenal Ulcer

OralDosage of choice: 800 mg once daily at bedtime.117 118 119

Patients with ulcer >1 cm in diameter who are heavy smokers (i.e., ≥1 pack daily) when rapid healing (e.g., within 4 weeks) is considered important:118 1.6 g daily at bedtime.117 118 119

Administer for 4–6 weeks unless healing is confirmed earlier.117 118 If not healed or symptoms continue after 4 weeks, additional 2–4 weeks of full dosage therapy may be beneficial.118 More than 6–8 weeks at full dosage is rarely needed.118

Healing of active duodenal ulcers may occur in 2 weeks in some, and occurs within 4 weeks in most patients.117 118 119 120 121 122

Other regimens (no apparent rationale for these other than familiarity of use) that have been used:117 118 300 mg 4 times daily with meals and at bedtime; 200 mg 3 times daily and 400 mg at bedtime; 400 mg twice daily in the morning and at bedtime.b

Maintenance of Healing of Duodenal Ulcer

Oral400 mg daily at bedtime.118 Efficacy not increased by higher dosages or more frequent administration.b

Pathologic GI Hypersecretory Conditions

Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome

Oral300 mg 4 times daily with meals and at bedtime.118

Higher doses administered more frequently may be necessary;a b adjust dosage according to response and tolerance but in general, do not exceed 2400 mg daily.a

Continue as long as necessary.118

Continuous IV InfusionMean infused dose of 160 mg/hour (range: 40-600 mg/hour) in one study.a

Gastric Ulcer

Oral

Preferred regimen: 800 mg once daily at bedtime.118

Alternative regimen: 300 mg 4 times daily, with meals and at bedtime.118

Monitor to ensure rapid progress to complete healing.a b

Studies limited to 6 weeks, efficacy for >8 weeks not established.118

GERD

Once daily (at bedtime) not considered appropriate therapy.288

Treatment of Symptomatic GERD† [off-label]

Oral300 mg 4 times daily has been used.105 106 123

Treatment of Erosive Esophagitis

Oral800 mg twice daily or 400 mg 4 times daily (e.g., before meals and at bedtime) for up to 12 weeks.118

Upper GI Bleeding

Prevention of Upper GI Bleeding

Continuous IV Infusion50 mg/hour; loading dose not required.118

Safety and efficacy of therapy beyond 7 days has not been established.118

Alternative dosage: Some clinicians recommend 300-mg IV loading dose over 5–20 minutes, then continuous IV infusion at 37.5–50 mg/hour; titrate with 25-mg/hour increments up to 100 mg/hour based on gastric pH (e.g., to maintain a pH of at least 3.5–4).118 143 144 173 174 176 188

Intermittent IV doses may be less effective in preventing upper GI bleeding than continuous IV infusion.155 172 173 174 175 176 177 178 188 189 191

Treatment of Upper GI Bleeding† [off-label]

Oral1–2 g daily in 4 divided doses has been used.b

IV1–2 g daily in 4 divided doses has been used.b

Heartburn, Acid Indigestion, or Sour Stomach

Heartburn (Self-medication)

Oral200 mg once or twice daily, or as directed by clinician.268

Maximum 400 mg in 24 hours, but not continuously for >2 weeks except under clinician supervision.c

Prevention of Heartburn (Self-medication)

Oral200 mg once or twice daily or as directed by a clinician; administer immediately (or up to 30 minutes) before ingestion of causative food or beverage.c

Maximum 400 mg in 24 hours, but not continuously for >2 weeks except under clinician supervision.c

Prescribing Limits

Pediatric Patients

Heartburn, Acid Indigestion, or Sour Stomach

Heartburn (Self-Medication)

OralAdolescents ≥12 years of age: Maximum 400 mg in 24 hours, but not continuously for >2 weeks except under clinician supervision.c

Prevention of Heartburn (Self-medication)

OralAdolescents ≥12 years of age: Maximum 400 mg in 24 hours, but not continuously for >2 weeks except under clinician supervision.c

Adults

General Parenteral Dosage

General parenteral dosage (hospitalized patients with pathologic hypersecretory conditions or intractable duodenal ulcer, or short-term use when oral therapy is not feasible):

Direct IV injection

Maximum 2.4 g daily.a

Maximum 300 mg per dose.a

Maximum concentration 300 mg/20 mL.a

Maximum injection rate: 20 mL over not less than 5 minutes (4 mL per minute).a

Intermittent IV Infusion

Maximum 2.4 g daily.a

Maximum 300 mg per dose.a

Maximum concentration 300 mg/50 mL.a

Maximum infusion rate: 15–20 minutes.a

GERD

Short-term Treatment of Erosive Esophagitis

OralSafety and efficacy beyond 12 weeks of administration have not been established.a

Heartburn, Acid Indigestion, or Sour Stomach

Heartburn Relief (Self-medication)

OralMaximum 400 mg in 24 hours, but not continuously for >2 weeks except under clinician supervision.c

Prevention of Heartburn (Self-medication)

OralMaximum 400 mg in 24 hours, but not continuously for >2 weeks except under clinician supervision.c

Duodenal Ulcer

Intermittent Direct IV Injecton

Maximum 2.4 g daily.a

Intermittent IV Infusion

Maximum 2.4 g daily.a

Gastric Ulcer

Short-term treatment of Active Benign Gastric Ulcer

OralSafety and efficacy beyond 8 weeks have not been established.118

Intermittent Direct IV InjectionMaximum 2.4 g daily.a

Intermittent IV InfusionMaximum 2.4 g daily.a

Pathologic GI Hypersecretory Conditions (e.g., Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome)

Oral

Maximum usually 2.4 g daily.118

Intermittent Direct IV Injection

Maximum 2.4 g daily.a

Intermittent IV Infusion

Maximum 2.4 g daily.a

Upper GI Bleeding

Prevention of Upper GI Bleeding

Continuous IV InfusionSafety and efficacy beyond 7 days have not been established.a

Special Populations

Renal Impairment

Severe (Clcr< 30 mL/minute)

Oral

300 mg every 12 hours.118

Accumulation may occur; use lowest frequency of dosing compatible with adequate response.118

Increase frequency to every 8 hours or more frequently (with caution) if required.118

Presence of hepatic impairment may require further dosage reduction.118

Direct IV Injection

300 mg every 12 hours.118

Accumulation may occur; use lowest frequency compatible with adequate response.118

Increase frequency to every 8 hours or more frequently (with caution) if required118

Presence of hepatic impairment may require further dosage reduction.118

Continuous IV Infusion

Prevention of Upper GI Bleeding: One-half recommended dosage (i.e., 25 mg/hour).118

Hemodialysis

Decreases blood levels; administer at the end of hemodialysis and every 12 hours during interdialysis.b

Hepatic Impairment

May require further dosage reduction in the presence of severe renal impairment.118

Cautions for Cimetidine, Cimetidine Hydrochloride

Contraindications

-

Known hypersensitivity to cimetidine or any ingredient in the formulation.118

Warnings/Precautions

General Precautions

Cardiovascular Effects

Rapid IV administration associated rarely with hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias; avoid.a b

Gastric Malignancy

Response to cimetidine does not preclude presence of gastric malignancy.118

CNS Effects

Reversible confusional states reported, especially in geriatric (i.e., ≥50 years) and severely ill (e.g., hepatic or renal disease, organic brain syndrome) patients.118 b Usually occurs within 2–3 days after initiating cimetidine and resolves within 3–4 days after discontinuance.118 b

Respiratory Effects

Administration of H2-receptor antagonists has been associated with an increased risk for developing certain infections (e.g., community-acquired pneumonia).302 303

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Category B.a

Pregnant women should consult a clinician before using for self-medication.268

Lactation

Distributed into milk.118 Generally, do not nurse during therapy with cimetidine.118

Nursing women should consult a clinician before using for self-medication.268

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy not established in children <16 years of age; do not use unless potential benefits outweigh risks.118

Safety and efficacy for self-medication not established in children <12 years of age; do not use unless directed by a clinician.c

Renal Impairment

Dosage adjustments necessary in patients with severe renal impairment.118

Hepatic Impairment

Further dosage adjustments may be necessary in presence of severe renal impairment.118

Immunocompromised Patients

Increased possibility of Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection with decreased gastric acidity.118 269 270

Common Adverse Effects

Headache,118 144 dizziness, somnolence, diarrhea.118

With ≥1 month of therapy: gynecomastia.118 b

With IM therapy: transient pain at injection site.118

Drug Interactions

Inhibits hepatic microsomal enzyme systems, decreases hepatic metabolism of some drugs.118 If necessary, adjust dosage of hepatically metabolized drugs when cimetidine therapy is initiated or discontinued.b

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Alcohol |

Possible increased blood alcohol concentrations,256 257 258 259 260 261 263 264 265 psychomotor impairment256 257 258 259 260 261 267 |

Potential for psychomotor impairment controversial, 256 257 258 259 260 261 267 but use caution during performance of hazardous tasks requiring mental alertness, physical coordination257 258 261 |

|

Antacidsb |

Decreased cimetidine absorptionb |

Administer 1 hour before or after cimetidine in the fasting state, or 1 hour after cimetidine is taken with food.a b |

|

Benzodiazepines118 |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of certain benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, triazolam)118 |

Adjust dosage if needed b |

|

Calcium-channel blockers (e.g., nifedipine)a |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of nifedipine118 |

Adjust dosage if needed b |

|

Ketoconazole118 |

Absorption of ketoconazole may be affected by altered gastric pH118 |

Administer ≥2 hours before cimetidine118 |

|

Lidocaine118 |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of lidocaine118 |

Adverse effects reported, adjust dosage if needed b |

|

Metronidazole118 |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of metronidazole118 |

Adjust dosage if neededb |

|

Myelosuppressive drugs (e.g., alkylating agents [e.g., carmustine], antimetabolites) and/or therapies (radiation)b |

May potentiate myelosuppressionb |

|

|

Phenytoin118 |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of phenytoin118 |

Adverse effects reported, adjust dosage if needed b |

|

Propranolol118 |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of propranolol118 |

Adjust dosage if needed b |

|

Theophylline118 |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of theophylline118 |

Adverse effects reported, adjust dosage if needed b |

|

Triamterene108 |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of triamterene118 |

Consider potential of clinically important interaction108 |

|

Tricyclic Antidepressants118 |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of certain tricyclic antidepressants118 |

Adjust dosage if neededb |

|

Warfarin118 |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of warfarin118 |

Monitor PT, adjust dosage if neededb |

Cimetidine, Cimetidine Hydrochloride Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Oral: 60–70%.b

Onset

≥70% decrease in basal acid secretion within 45 minutes after single 300- or 400-mg IV dose in healthy males.100

Duration

|

Dosage Regimen |

Effect On Acid Secretion |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Oral: 800 mg at bedtime in duodenal ulcer patients118 |

Mean hourly nocturnal secretion decreased by 85% over 8 hours.118 |

No effect on daytime acid secretion118 |

|

Oral: 1600 mg at bedtime in duodenal ulcer patients 118 |

Mean hourly nocturnal secretion decreased by 100% over 8 hours, 35% decrease for additional 5 hours.118 |

Moderate (<60%) 24-hour suppression118 |

|

Oral: 400 mg twice daily in duodenal ulcer pateints118 |

Nocturnal secretion decreased by 47–83% over 6–8 hours 118 |

Moderate (<60%) 24-hour suppression118 |

|

Oral: 300 mg 4 times daily in duodenal ulcer patients118 |

Nocturnal secretion decreased by 54% over 9 hours118 |

Moderate (<60%) 24-hour suppression118 |

|

Oral: Single 300-mg dose within 1 hour after meal in duodenal ulcer patientsa |

Food-stimulated secretion decreased by 50% for 1 hour, then 75% for 2 hours.a |

|

|

Oral: 300-mg dose at breakfast in duodenal ulcer patientsa |

Continued suppression for 4 hours, with partial suppression after luncha |

Effect enhanced and maintained by additional 300-mg dose with luncha |

|

Oral: 300-mg dose with foodb |

Mean gastric pH 3.5–4 at 1 hour, 5.5–6.1 at 4 hoursb |

|

|

Oral: Single dose 300 mg with fooda |

Mean gastric pH: 3.5, 3.1, 3.8, 6.1 at hour 1, 2, 3, 4, respectivelya |

Placebo mean gastric pH: 2.6, 1.6, 1.9, 2.2 at hour 1, 2, 3, 4, respectivelya |

|

Oral: 300–400 mg in fasting state in duodenal ulcer patientsb |

Anacidity for up to 8 hoursb |

|

|

Oral: 300 mg in duodenal ulcer patientsb |

Basal gastric acid output decreased by 90% for 4 hoursb |

Meal-stimulated acid secretion by 66% for 3 hoursb |

|

IV continuous infusion: mean dosage of 160 mg/hour (range:40-600 mg/hour) in pathologic hypersecretory conditionsb |

Maintained secretion at ≤10 mEq/hourb |

|

|

IV continuous infusion (37.5 mg/hour or 900 mg daily) in patients with active or healed duodenal or gastric ulcerb |

Maintained gastric pH at >4 for >50% of the time at steady-state.b |

|

|

Intermittent injection: (300 mg every 6 hours or 1200 mg daily) in patients with active or healed duodenal or gastric ulcerb |

Maintained gastric pH at >4 for >50% of the time at steady-state.b |

|

|

IV: Single 300- or 400-mg dose in healthy males |

≥70% decrease in basal acid secretion maintained for 4–4.5 hours100 |

Food

Delays, slightly decreases absorption.b However, administration with meals achieves maximum blood concentrations and antisecretory effect when stomach is no longer protected by food buffering effect.b

Distribution

Extent

Widely distributed throughout the body.b

Distributed into human milk.b

Crosses the placenta in animals.b

Plasma Protein Binding

15–20%.b

Elimination

Metabolism

Metabolized to sulfoxide (major metabolite) and 5-hydroxymethyl derivatives in liver.a b More extensively metabolized after oral than parenteral administration.a

Elimination Route

Excreted principally in urine.a b Single oral dose: 48% (unchanged) excreted in urine over 24 hours.a IV or IM: about 75% (unchanged) excreted in urine within 24 hours.a Single IV dose of radiolabeled cimetidine: 80–90% (50–73% unchanged, remainder as metabolites) excreted in urine over 24 hours.b About 10% excreted in feces.b

Half-life

2 hours.a

After IV administration in children 4.1–15 years of age: Apparent biphasic decline of plasma cimetidine and cimetidine sulfoxide concentrations with half-lives of 1.4 and 2.6 hours, respectively.102

Special Populations

2.9 hours in patients with Clcr 20–50 mL/minute.b 3.7 hours in patients with Clcr <20 mL/minute.b 5 hours in anephric patients.b

Stability

Storage

Oral

Liquid and Tablets

Tight, light-resistant containers at 15–30°C.b

Parenteral

Injection

15–30°C.b Protect from light.b Do not refrigerate.b Stable in most IV solutions for at least 3 days at room temperature in concentrations of 1.2–5 mg/mL,b but use within 48 hours when diluted as directed.118 b

Injection for IV infusion only

15–30°C.b Protect from excessive heat; brief exposure up to 40°C does not adversely affect stability.b Stable through the labeled expiration date when stored as recommended.118

Actions

-

Inhibits basal and stimulated gastric acid secretion.b

-

Competitively inhibits histamine at parietal cell H2 receptors.b

-

Weak antiandrogenic effect.b

Advice to Patients

-

Importance of patients informing clinician of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs.289

-

Importance of taking antacids on an empty stomach 1 hour before or 1 hour after oral administration of cimetidine, or 1 hour after the drug is taken with food,b but not at same time as oral cimetidine.a b

-

Importance of women informing clinician if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.289

-

Before self-medication, importance of consulting clinician if taking warfarin, theophylline, or phenytoin.268

-

Importance of following dosage instructions when cimetidine is administered for self-medication, unless otherwise directed by a clinician.c

-

Importance of promptly informing clinician of persistent abdominal pain or difficulty swallowing.268

-

Importance of informing patients of other important precautionary information.

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer’s labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Solution |

300 mg/mL* |

Cimetidine Hydrochloride Oral Solution |

Actavis |

|

Tagamet (with parabens, povidone, and propylene glycol) |

GlaxoSmithKline |

|||

|

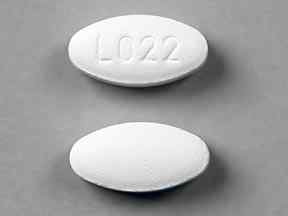

Tablets, film-coated |

200 mg* |

Tagamet HB 200 |

GlaxoSmithKline |

|

|

Tagamet HB (with povidone) |

GlaxoSmithKline |

|||

|

300 mg* |

Tagamet (with povidone and propylene glycol) |

GlaxoSmithKline |

||

|

400 mg* |

Tagamet Tiltab (with povidone and propylene glycol) |

GlaxoSmithKline |

||

|

800 mg* |

Tagamet Tiltab (with povidone and propylene glycol; scored) |

GlaxoSmithKline |

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Solution |

300 mg (of cimetidine) per 5 mL* |

Tagamet HCl (with alcohol 2.8% parabens and propylene glycol) |

GlaxoSmithKline |

|

Parenteral |

Injection |

150 mg (of cimetidine) per mL |

Cimetidine Hydrochloride Injection |

Endo |

|

Injection, for IV infusion only |

150 mg (of cimetidine) per mL |

Cimetidine Hydrochloride ADD-Vantage |

Hospira |

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Parenteral |

Injection, for IV infusion only |

6 mg (of cimetidine) per mL (300, 900, or 1200 mg) in 0.9% Sodium Chloride |

Cimetidine HCl in 0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection (available in flexible plastic container) |

Hospira |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions October 10, 2024. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

Only references cited for selected revisions after 1984 are available electronically.

100. Frank WO, Peace KE, Watson M et al. The effect of single intravenous doses of cimetidine or ranitidine on gastric secretion. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1986; 40:665-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3780128

101. Peterson WL, Richardson CT. Intravenous cimetidine or two regimens of ranitidine to reduce fasting gastric acidity. Ann Intern Med. 1986; 104:505-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3954278

102. Lloyd CW, Martin WJ, Taylor BD et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cimetidine and metabolites in critically ill children. J Pediatr. 1985; 107:295-300. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4020559

103. Richter JE. Treatment of severe reflux esophagitis. Ann Intern Med. 1986; 104:588-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2869728

104. Glaxo Inc. Zantac tablets prescribing information. Research Triangle Park, NC; 1986 Jun.

105. Lieberman DA, Keeffe EB. Treatment of severe reflux esophagitis with cimetidine and metoclopramide. Ann Intern Med. 1986; 104:21-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3940501

106. Castell DO. Medical therapy for reflux esophagitis: 1986 and beyond. Ann Intern Med. 1986; 104:112-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2866742

107. Temple JG, Bradby GV, O’Connor FO et al. Cimetidine and metoclopramide in oesophageal reflux disease. BMJ. 1983; 286:1863-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6407606

108. Muirhead MR, Somogyi AA, Rolan PE et al. Effect of cimetidine on renal and hepatic drug elimination: studies with triamterene. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1986; 40:400-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3757403

109. Parenti CM, Hoffman JE. Hyperpyrexia associated with intravenous cimetidine therapy: report of a case. Arch Intern Med. 1986; 146:1821-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3753124

110. Landolfo K, Low DE, Rogers AG. Cimetidine-induced fever. Can Med Assoc J. 1984; 130:1580. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6733633

111. Potter HP Jr, Byrne EB, Lebovitz S. Fever after cimetidine and ranitidine. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986; 8(3 Part 1):275-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3734359

112. Ramboer C. Drug fever with cimetidine. Lancet. 1978; 1:330-1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/75368

113. McLoughlin JC, Callender ME, Love AHG. Cimetidine fever. Lancet. 1978; 1:499-500.

114. Corbett CL, Holdsworth CD. Fever, abdominal pain and leucopenia. Br Med J. 1978; 1:753-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/630330

115. Nistico G, Rotiroti D, de Sarro A et al. Mechanism of cimetidine-induced fever. Lancet. 1978; 2:265-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/79060

116. Randolph WC, Peace KE, Seaman JJ et al. Bioequivalence of a new 800-mg cimetidine tablet with commercially available 400-mg tablets. Curr Ther Res. 1986; 39:767-72.

117. Lewis JH. Summary of the 30th meeting of the Food and Drug Administration Gastrointestinal Drugs Advisory Committee: January 16–17, 1986. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986; 81:495-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3518411

118. SmithKline Beecham. Tagamet (cimetidine tablets, cimetidine hydrochloride liquid, and cimetidine hydrochloride injection) prescribing information. Philadelphia, PA; 1994 Jul.

119. Seaman JJ (Smith Kline French Laboratories, Philadelphia, PA): Personal communication; 1985 Oct.

120. Delattre M, Dickson B. Cimetidine once daily. Lancet. 1984; 1:625. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6142325

121. Howden CW, Jones DB, Hunt RH. Nocturnal doses of H2 receptor antagonists for duodenal ulcer. Lancet. 1985; 1:647-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2857992

122. Capurso L, Dal Monte PR, Mazzeo F et al. Comparison of cimetidine 800 mg once daily and 400 mg twice daily in acute duodenal ulceration. BMJ. 1984; 289:1418-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6437579

123. Behar J, Brand DL, Browr FC et al. Cimetidine in the treatment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux: a double blind controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 1978; 74(2 Part 2):441-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/340333

124. Carpenter GB, Bunker-Soler AL, Nelson HS. Evaluation of combined H1- and H2-receptor blocking agents in the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1983; 71:412-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6131914

125. Smith Laboratories, Inc. Chymodiactin (chymopapain for injection) prescribing information. Northbrook, IL; 1985 Jun.

126. Deutsch PH. Dermatographism treated with hydroxyzine and cimetidine and ranitidine. Ann Intern Med. 1984; 101:569. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6089638

127. Cook J, Shuster S. The effect of H1 and H2 receptor antagonists on the dermographic response. Acta Derm Venereol. 1983; 63:260-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6192650

128. Mansfield LE, Smith JA, Nelson HS. Greater inhibition of dermographia with a combination of H1 and H2 antagonists. Ann Allergy. 1983; 50:264-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6132569

129. Irwin RB, Lieberman P, Friedman MM et al. Mediator release in local heat urticaria: protection with combined H1 and H2 antagonists. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1985; 76:35-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2861221

130. Farnam J, Grant JA, Lett-Brown MA et al. Combined cold- and heat-induced cholinergic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1986; 78:353-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3734288

131. Duc J, Pecoud A. Successful treatment of idiopathic cold urticaria. Ann Allergy. 1986; 56:355-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2870670

132. Singh G. H2 blockers in chronic urticaria. Int J Dermatol. 1984; 23:627-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6151554

133. Harvey RP, Wegs J, Schocket AL. A controlled trial of therapy in chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1981; 68:262-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6116728

134. Harvey RP, Schocket AL. The effect of H1 and H2 blockade on cutaneous histamine response in man. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1980; 65:136-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6101337

135. Monroe EW, Cohen SH, Kalbfleisch J et al. Combined H1 and H2 antihistamine therapy in chronic urticaria. Arch Dermatol. 1981; 117:404-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6114712

136. Farnam J, Grant JA, Guernsey BG et al. Successful treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria and angioedema with cimetidine alone. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1984; 73:842-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6725793

137. Kulczycki A Jr. Aspartame-induced urticaria. Ann Intern Med. 1986; 104:207-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3946947

138. Travenol Laboratories, Inc. Descriptive information on premixed Mini-Bag container frozen products. Travenol Laboratories, Inc.: Deerfield, IL; 1987 Jun.

139. Lesser IM, Miller BL, Boone K et al. Delusions in a patient treated with histamine H2 receptor antagonists. Psychosomatics. 1987; 28:501-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3432552

140. Romisher S, Felter R, Dougherty J. Tagamet-induced acute dystonia. Ann Emerg Med. 1987; 16:1162-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3662164

141. Cantú TG, Korek JS. Central nervous system reactions to histamine-2 receptor blockers. Ann Intern Med. 1991; 114:1027-34. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1674198

142. SmithKline Beecham, Philadelphia, PA: Personal communication.

143. Karlstadt RG, Iberti TJ, Silverstein J et al. Comparison of cimetidine and placebo for the prophylaxis of upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to stress-related gastric mucosal damage in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 1990; 5:26-32.

144. Karlstadt R, D’Ambrosio C, McCafferty J et al. Cimetidine is effective prophylaxis against upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the intensive care unit. Paper presented at the 9th World Congress of Gastroenterology. Sydney, Australia: 1990 Aug 26-31.

145. Basso N, Bagarani M, Materia A et al. Cimetidine and antacid prophylaxis of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in high risk patients. Am J Surg. 1981; 141:339-41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7011078

146. Moscona R, Kaufman T, Jacobs R et al. Prevention of gastrointestinal bleeding in burns: the effects of cimetidine or antacids combined with early enteral feeding. Burns. 1985; 12:65-7.

147. Nagasue N, Yukaya H, Ogawa Y et al. Prophylaxis of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with cimetidine in patients undergoing partial hepatectomy. Ann Chirurg Gyn. 1984; 73:6-10.

148. Groll A, Simon JB, Wigle RD et al. Cimetidine prophylaxis for gastrointestinal bleeding in an intensive care unit. Gut. 1986; 27:135-40. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3485068

149. Priebe HJ, Skillman JJ, Bushnell LS et al. Antacid versus cimetidine in preventing acute gastrointestinal bleeding: a randomized trial in 75 critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 1980; 302:426-30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6986027

150. Chan KH, Mann KS. Failure of cimetidine prophylaxis in neurosurgery. Aust NZ J Surg. 1989; 59:133-6.

151. Karlstadt R, Palmer RH. Gastric pH control and pneumonia in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med. 1990; 16:346. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2212268

152. Halloran LG, Zfass AM, Gayle MW et al. Prevention of acute gastrointestinal complications after severe head injury: a controlled trial of cimetidine prophylaxis. Am J Surg. 1980; 139:44-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6985776

153. Lacroix J, Infante-Rivard C, Jenicek M et al. Prophylaxis of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in intensive care units: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 1989; 17:862-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2670450

154. Lacroix J, Infante-Rivard C, Gauthier M. Prophylaxis of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in intensive care units: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 1991; 18:1492-3.

155. Cook DJ, Witt LG, Cook RJ et al. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in the critically ill: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 1991; 91:519-27. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1835294

156. Shuman RB, Schuster DP, Zuckerman GR. Prophylactic therapy for stress ulcer bleeding: a reappraisal. Ann Intern Med. 1987; 106:562-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3548524

157. Reusser P, Gyr K, Scheidegger D et al. Prospective endoscopic study of stress erosions and ulcers in critically ill neurosurgical patients: current incidence and effect of acid-reducing prophylaxis. Crit Care Med. 1990; 18:2704.

158. Reines HD. Do we need stress ulcer prophylaxis? Crit Care Med. 1990; 18:344. Editorial.

159. Goetting MG. Stress ulcers in the neurosurgical critical care patient. Crit Care Med. 1991; 19:446. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1999114

160. Goetting MG. Stress ulcers in the neurosurgical critical care patient. Crit Care Med. 1991; 19:446-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1999114

161. Zuckerman GR, Shuman R. Therapeutic goals and treatment options for prevention of stress ulcer syndrome. Am J Med. 1987; 83(Suppl 6A):29-35. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3321975

162. Miller TA. Mechanisms of stress-related mucosal damage. Am J Med. 1987; 83(Suppl 6A):8-14. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3321980

163. Friedman CJ, Oblinger MJ, Suratt PM et al. Prophylaxis of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage in patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 1982; 10:316-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7042201

164. Stothert JC Jr, Simonowitz DA, Dellinger EP et al. Randomized prospective evaluation of cimetidine and antacid control of gastric pH in the critically ill. Ann Surg. 1980; 192:169-74. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7406571

165. Halloran LG, Zfass AM, Gayle WE et al. Prevention of acute gastrointestinal complications after severe head injury: a controlled trial of cimetidine prophylaxis. Am J Surg. 1980; 139:44-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6985776

166. Zinner MJ, Zuidema GD, Smith PL et al. The prevention of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding in patients in an intensive care unit. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1981; 153:214-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7017982

167. Hastings PR, Skillman JJ, Bushnell LS et al. Antacid titration in the prevention of acute gastrointestinal bleeding: a controlled, randomized trial in 100 critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 1978; 298:1041-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25384

168. McAlhany JC Jr, Colmic L, Czaja AJ et al. Antacid control of complications from acute gastroduodenal disease after burns. J Trauma. 1976; 16:645-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/785019

169. Adeyemi SD, Ein SH, Simpson JS. Perforated stress ulcer in infants: a silent threat. Ann Surg. 1979; 190:706-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/518170

170. Peura DA, Johnson LF. Cimetidine for prevention and treatment of gastroduodenal mucosal lesions in patients in an intensive care unit. Ann Intern Med. 1985; 103:173-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3874573

171. Lacroix J, Infante-Rivard C, Gauthier M et al. Clinical and laboratory observations: upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding acquired in a pediatric intensive care unit: prophylaxis trial with cimetidine. J Pediatr. 1986; 108:1015-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3519913

172. Martin LF, Booth FV, Reines HD et al. Stress ulcers and organ failure in intubated patients in surgical intensive care units. Ann Surg. 1992; 215:332-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1558413

173. Siepler JK, Trudeau W, Petty DE. Use of continuous infusion of histamine2-receptor antagonists in critically ill patients. DICP Ann Pharmacother. 1989; 23(Suppl)S40-3. (IDIS 260919)

174. Ostro MJ, Russel JA, Soldin SJ et al. Control of gastric pH with cimetidine: boluses versus primed infusions. Gastroenterology. 1985; 89:532-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4018499

175. Tryba M, Zevounou F, Torok M et al. Prevention of acute stress bleeding with sucralfate, antacids, or cimetidine: a controlled study with pirenzepine as a basic medication. Am J Med. 1985; 79(Suppl 2C):55-61. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3876031

176. Siepler JK. A dosage alternative for H2-receptor antagonists—constant infusion. Clin Ther. 1986; 8(Suppl A):24-33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2878728

177. Cannon LA, Heiselman D, Gardner W et al. Prophylaxis of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding in mechanically ventilated patients: a randomized study comparing the efficacy of sucralfate, cimetidine, and antacids. Arch Intern Med. 1987; 147:2101-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3500684

178. Levinson MJ. Gastric stress ulcers. Hosp Pract. (Office Ed). 1989; (March 30):59-68.

179. Strembo MA, Karlstadt RG. H2 blockers in stress ulcer prophylaxis. Hosp Pract. (Office Ed). 1989; (October 30):17,20.

180. Karlstadt RG, Palmer RH. Risk factors in nosocomial pneumonia in intensive care. Arch Intern Med. 1990; 150:919. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2360954

181. Maki DG. Risk factors for nosocomial infection in intensive care: “devices vs nature” and goals for the next decade. Arch Intern Med. 1989; 149:30-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2643417

182. Craven DE, Kunches LM, Kilinshky V et al. Risk factors for pneumonia and fatality in patients receiving continuous mechanical ventilation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986; 133:792-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3706887

183. Craven DE, Kunches LM, Lichtenberg DA et al. Nosocomial infection and fatality in medical and surgical intensive care unit patients. Arch Intern Med. 1988; 148:1161-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3365084

184. Driks MR, Craven DE, Celli BR et al. Nosocomial pneumonia in intubated patients given sucralfate as compared with antacids or histamine type 2 blockers: the role of gastric colonization. N Engl J Med. 1987; 317:1376-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2891032

185. Reusser P, Zimmerli W, Scheidegger D et al. Role of gastric colonization in nosocomial infections and endotoxemia: a prospective study in neurosurgical patients on mechanical ventilation. J Infect Dis. 1989; 160:414-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2760497

186. Tryba M. Risk of acute stress bleeding and nosocomial pneumonia in ventilated intensive care unit patients: sucralfate versus antacids. Am J Med. 1987; 83(Suppl 3B):117-24. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3310626

187. Cook DJ, Laine LA, Guyatt GH et al. Nosocomial pneumonia and the role of gastric pH: a meta-analysis. Chest. 1991; 100:7-13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1676361

188. Wilcox CM. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in medical patients: who, what, and how much? Am J Gastroenterol. 1988; 83:1199-1211.

189. Peura DA. Controversies, dilemmas, and dialogues. Prophylactic therapy of stress-related mucosal damage: why, which, who, and so what? Am J Gastroenterol. 1990; 85:935-6. Editorial. (IDIS 288383)

190. Koretz RL. Controversies, dilemmas, and dialogues. Prophylactic therapy of stress-related mucosal damage: why, which, who, and so what? Am J Gastroenterol. 1990; 85:936-7. Editorial.

191. Kingsley AN. Prophylaxis for acute stress ulcers: antacids or cimetidine. Am Surg. 1985; 51:545-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3898949

192. Martin LF, Max MH, Polk HC Jr. Failure of gastric pH control by antacids or cimetidine in the critically ill: a valid sign of sepsis. Surgery. 1980; 88:59-68. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6966835

193. Reviewers’ comments (personal observations).

194. SmithKline Beecham. Philadelphia, PA: Personal communication.

195. Peura DA, Koretz RL. Should patients in the intensive care unit be provided routinely with antacids, sucralfate, or H2 blocker prophylaxis to prevent stress bleeding? In: Gitnick G, Barnes HV, Duffy TP et al eds. Debates in Medicine. Chicago, IL: Mosby—Year Book, Inc; 1991; 4:230-55.

196. Martin LF, McBooth FV, Karlstadt RG et al. Continuous intravenous cimetidine decreased stress-related upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage without promoting pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 1991 (in press).

197. Baxter Healthcare Corporation. Descriptive information on premixed liquid products. Deerfield, IL; 1992 Sep.

198. Anon. Safety of terfenadine and astemizole. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1992; 34:9-10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1732711

199. Ateshkadi A, Lam NP, Johnson CA. Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease. Clin Pharm. 1993; 12:34-48. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8428432

200. Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori: its role in disease Clin Infect Dis. 1992; 15:386-91.

201. Murray DM, DuPont HL, Cooperstock M et al. Evaluation of new anti-infective drugs for the treatment of gastritis and peptic ulcer disease associated with infection by Helicobacter pylori . Clin Infect Dis. 1992; 15(Suppl 1):S268-73.

202. Peterson WL. Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease. N Engl J Med. 1991; 324:1043-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2005942

203. Graham DY, Go MF. Evaluation of new antiinfective drugs for Helicobacter pylori infection: revisited and updated. Clin Infect Dis. 1993; 17:293-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8399892

204. Murray DM, DuPont HL. Reply. (Evaluation of new antiinfective drugs for Helicobacter pylori infection: revisited and updated.) Clin Infect Dis. 1993; 17:294-5.

205. George LL, Borody TJ, Andrews P et al. Cure of duodenal ulcer after eradication of H. pylori . Med J Aust. 1990; 153:145-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1974027

206. Farrell MK. Dr. Apley meets Helicobacter pylori . J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993; 16:118-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8450375

207. Fiocca R, Solcia E, Santoro B. Duodenal ulcer relapse after eradication of Helicobacter pylori . Lancet. 1991; 337:1614. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1675746

208. Marshall BJ. Campylobacter pylori: Its link to gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1990; 12(Suppl 1):S87-93.

209. Graham DY, Lew GM, Evans DG et al. Effect of triple therapy (antibiotics plus bismuth) on duodenal ulcer healing. A randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1991; 115:266-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1854110

210. Reviewers’ comments (personal observations) on Helicobacter pylori.

211. Glassman MS. Helicobacter pylori infection in children. A clinical overview. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1992; 31:481-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1643767

212. Marshall BJ. Treatment strategies for Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1993; 22:183-98. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8449566

213. Chiba N, Rao BV, Rademaker JW et al. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of antibiotic therapy in eradicating Helicobacter pylori . Am J Gastroenterol. 1992; 87:1716-27. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1449132

214. Bianchi Porro G, Parente F, Lazzaroni M. Short and long term outcome of Helicobacter pylori positive resistant duodenal ulcers treated with colloidal bismuth subcitrate plus antibiotics or sucralfate alone. Gut. 1993; 34:466-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8491391

215. Borody T, Andrews P, Mancuso N et al. Helicobacter pylori reinfection 4 years post-eradication. Lancet. 1992; 339:1295. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1349686

216. Hixson LJ, Kelley CL, Jones WN et al. Current trends in the pharmacotherapy for peptic ulcer disease. Arch Intern Med. 1992; 152:726-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1558429

217. Rauws EAJ, Tytgat GNJ. Cure of duodenal ulcer with eradication of Helicobacter pylori . Lancet. 1990; 335:1233-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1971318

218. Hentschel E, Brandstätter G, Dragosics B et al. Effect of ranitidine and amoxicillin plus metronidazole on the eradication of Helicobacter pylori and the recurrence of duodenal ulcer. N Engl J Med. 1993; 328:308-12. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8419816

219. Sloane R, Cohen H. Commonsense management of Helicobacter pylori-associated gastroduodenal disease. Personal views. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1993; 22:199-206. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8449567

220. Katelaris P. Eradicating Helicobacter pylori . Lancet. 1992; 339:54. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1345965

221. Burette A, Glupczynski Y. On: The who’s and when’s of therapy for Helicobacter pylori . Am J Gastroenterol. 1991; 86:924-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2058644

222. Bell GD, Powell K, Burridge SM et al. Experience with ″triple’ anti-Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: side effects and the importance of testing the pretreatment bacterial isolate for metronidazole resistance. Ailment Pharmacol Ther. 1992; 6:427-35.

223. Ateshkadi A, Lam NP, Johnson CA. Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease. Clin Pharm. 1993; 12:34-48. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8428432

224. Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori: its role in disease. Clin Infect. 1992; 15:386-91.

225. Marshall BJ. Treatment strategies for Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1993; 22:183-98. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8449566

226. Bayerdorffer E, Mannes GA, Sommer A et al. Long-term follow-up after eradication of Helicobacter pylori with a combination of omeprazole and amoxycillin. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1993; 196:19-25. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8341987

227. Unge P, Ekstrom P. Effects of combination therapy with omeprazole and an antibiotic on H. pylori and duodenal ulcer disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1993; 196:17-8.

228. Hunt RH. Hp and pH: implications for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1993; 196:12-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8341986

229. Malfertheiner P. Compliance, adverse events and antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori treatment. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1993; 196:34-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8341989

230. Bell GD, Powell U. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and its effect in peptic ulcer disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1993; 196:7-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8341990

231. Farrell MK. Dr. Apley meets Helicobacter pylori. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993; 16:118-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8450375

232. Nomura A, Stemmermann GN, Chyou PH et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:1132-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1891021

233. Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:1127-31. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1891020

234. An international association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. The EUROGAST Study Group. Lancet. 1993; 341:1359-62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8098787

235. Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Weaver A et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma and Helicobacter pylori infection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991; 83:1734-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1770552

236. Forman D, Newell DG, Fullerton F et al. Association between infection with Helicobacter pylori and risk of gastric cancer: evidence from a prospective investigation. BMJ. 1991; 302:1302-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2059685

237. Forman D. Helicobacter pylori infection: a novel risk factor in the etiology of gastric cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991; 83:1702-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1770545

238. Parsonnet J. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1993; 22:89-104. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8449573

239. Correa P. Is gastric carcinoma an infectious disease? N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:1170-1.

240. Isaacson PG, Spencer J. Is gastric lymphoma an infectious disease? Hum Pathol. 1993; 24:569-70.

241. Rauws EAJ, Tytgat GNJ. Cure of duodenal ulcer with eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1990; 335:1233-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1971318

242. Hunt RH. pH and Hp—gastric acid secretion and Helicobacter pylori: implications for ulcer healing and eradication of the organism. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993; 88:481-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8470623

243. Reviewers’ comments (personal observations) on Helicobacter pylori; 1993 Oct 26.

244. Marshall BJ. Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994; 89(Suppl):S116-28.

245. Labenz J, Gyenes E, Rühl GH et al. Amoxicillin plus omeprazole versus triple therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori in duodenal ulcer disease: a prospective, randomized, and controlled study. Gut. 1993; 34:1167-70. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8406147

246. Anon. Drugs for treatment of peptic ulcers. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1994; 36:65-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7912812

247. Freston JW. Emerging strategies for managing peptic ulcer disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1994; 201:49-54. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8047824

248. Axon ATR. The role of acid inhibition in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1994; 201:16-23. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8047818

249. Labenz J, Rühl GH, Bertrams J et al. Medium- or high-dose omeprazole plus amoxicillin eradicates Helicobacter pylori in gastric ulcer disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994; 89:726-30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8172146

250. Labenz J, Borsch G. Evidence for the essential role of Helicobacter pylori in gastric ulcer disease. Gut. 1994; 35:19-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8307443

251. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Helicobacter pylori in Peptic Ulcer Disease. Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease. JAMA. 1994; 272:65-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8007082

252. Fennerty MB. Helicobacter pylori. Ann Intern Med. 1994; 154:721-7.

253. Adamek RJ, Wegener M, Labenz J et al. Medium-term results of oral and intravenous omeprazole/amoxicillin Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994; 89:39-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8273795

254. Cotton P. NIH consensus panel urges antimicrobials for ulcer patients, skeptics concur with caveats. JAMA. 1994; 271:808-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8114221

255. Feldman M. The acid test. Making clinical sense of the consensus conference on Helicobacter pylori . JAMA. 1994; 272:70-1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8007084

256. Raufman JP, Notar-Francesco V, Raffaniello RD et al. Histamine-2 receptor antagonists do not alter serum ethanol levels in fed, nonalcoholic men. Ann Intern Med. 1993; 118:488-94. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8095127

257. Lewis JH, McIsaac RL. H2 antagonists and blood alcohol levels. Dig Dis Sci. 1993; 38:569-71. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8095199

258. Roine R, Hernández-Munoz R, Baraona E et al. H2 antagonists and blood alcohol levels. Dig Dis Sci. 1993; 38:572-3.

259. Anon. H2 blocker interaction with alcohol is not clinically significant, FDA advisory committee concludes March 12; issue may be revisited, agency indicates. FDC Rep Drugs Cosmet. 1993 Mar 22:10.

260. Levitt MD. Do histamine-2 receptor antagonists influence the metabolism of ethanol? Ann Intern Med. 1993; 118:564-5. Editorial.

261. Marshall JM. Interaction of histamine2-receptor antagonists and ethanol. Ann Pharmacother. 1994; 28:55-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7907240

262. Fraser AG, Prewett EJ, Hudson M et al. The effect of ranitidine, cimetidine or famotidine on low-dose post-prandial alcohol absorption. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1991; 5:263-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1888825

263. Fraser AG, Hudson M, Sawyer AM et al. Short report: the effect of ranitidine on the post-prandial absorption of a low dose of alcohol. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1992; 6:267-71. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1600045

264. Palmer RH, Frank WO, Nambi P et al. Effects of various concomitant medications on gastric alcohol dehydrogenase and the first-pass metabolism of ethanol. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991; 86:1749-55. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1683743

265. Gugler R. H2-antagonists and alcohol: do they interact? Drug Saf. 1994; 10:271-80.

266. Peura DA, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori: consensus reached: peptic ulcer is on the way to becoming an historic disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994; 89:1137-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8053422

267. Levine LR, Cloud ML, Enas NH. Nizatidine prevents peptic ulceration in high-risk patients taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Arch Intern Med. 1993; 153:2449-54. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8215749

268. SmithKline Beecham Consumer Healthcare. Tagamet HB (cimetidine) tablets product information. Pittsburgh, PA; 1995.

269. Cadranel JF, Eugene C. Another example of Strongyloides stercoralis infection associated with cimetidine in an immunosuppressed patient. Gut. 1986; 27:1229. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3781340

270. Ainley CC, Clarke DG, Timothy AR et al. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection associated with cimetidine in an immunosuppressed patient: diagnosis by endoscopic biopsy. Gut. 1986; 27:337-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3699555

271. Markham A, McTavish D. Clarithromycin and omeprazole: as Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in patients with H. pylori-associated gastric disorders. Drugs. 1996; 51:161-78. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8741237

272. Soll AH. Medical treatment of peptic ulcer disease. JAMA. 1996; 275:622-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8594244

273. Labenz J, Börsch G. Highly significant change of the clinical course of relapsing and complicated peptic ulcer disease after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994; 89:1785-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7942667

274. Wang WM, Chen CY, Jan CM et al. Long-term follow-up and serological study after triple therapy of Helicobacter pylori-associated duodenal ulcer. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994; 89:1793-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7942669

275. Walsh JH, Peterson WL. The treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in the management of peptic ulcer disease. N Engl J Med. 1995; 333:984-91. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7666920

276. Hackelsberger A, Malfertheiner P. A risk-benefit assessment of drugs used in the eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Drug Saf. 1996; 15:30-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8862962

277. Rauws EAJ, van der Hulst RWM. Current guidelines for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease. Drugs. 1995; 6:984-90.

278. van der Hulst RWM, Keller JJ, Rauws EAJ et al. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: a review of the world literature. Helicobacter. 1996; 1:6-19. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9398908

279. Lind T, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S, Unge P et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori using one-week triple therapies combining omeprazole with two antimicrobials: the MACH I study. Helicobacter. 1996; 1:138-44. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9398894

280. Anon. The choice of antibacterial drugs. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1996; 38:25-34. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8598824

281. Fennerty MB. Practice guidelines for treatment of peptic ulcer disease. JAMA. 1996; 276:1135. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8827957

282. Soll AH. Practice guidelines for treatment of peptic ulcer disease. JAMA. 1996; 276:1136-7.

283. TAP Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Prevacid (lansoprazole) delayed-release capsules prescribing information. Deerfield, IL; 1997 Aug.

284. Langtry HD, Wilde MI. Lansoprazole: an update of its pharmacological properties and clinical efficacy in the management of acid-related disorders. Drugs. 1997; 54:473-500. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9279507

285. Garnett RG. Lansoprazole: a proton pump inhibitor. Ann Pharmacother. 1996; 30:1425. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8968456

286. Zimmerman AE, Katona BG. Lansoprazole: a comprehensive review. Pharmacotherapy. 1997; 17:308-26. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9085323

287. Hatlebakk JG, Nesje LB, Hausken T et al. Lansoprazole capsules and amoxicillin oral suspension in the treatment of peptic ulcer disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995; 11:1053-7.

288. DeVault KR, Castell DO, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999; 94:1434-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10364004

289. Behar J, Brand DL, Brown FC et al. Cimetidine in the treatment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux. Gastroenterol. 1978; 74:441-8.

290. Sontag S, Robinson M, McCallum RW et al. Ranitidine therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Results of a large double-blind trial. Arch Intern Med. 1987; 1485-91.

291. Euler AR, Murdock RH, Wilson TH et al. Ranitidine is effective therapy for erosive esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993; 88:520-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8470632

292. Galmiche JP, Fraitag B, Filoche B et al. Double-blind comparison of cisapride and cimetidine in treatment of reflux esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1990; 35:649-55. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2331957

293. Lepoutre L, Vander Speck P. Vanderlinden I et al. Healing of greade-II and III oesophagitis through motility stimulation with cisapride. Digestion. 1990; 45:109-14. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2190850

294. Richter JE, Long JF. Cisapride for gastroesophageal reflux disease: A placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995; 90:423-30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7872282

295. Galmiche JP, Brandstatter G, Evreux M et al. Combined therapy with cisapride and cimetidine in severe reflux esophagitis: A double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Gut. 1988; 29:675-81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3294124

296. Ganzini L, Casey DE, Hofman WF et al. The prevalence of metoclopramide-induced tardive dyskinesia and acute extrapyramidal movement disorders. Arch Intern Med. 1993; 153:1469-75. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8512437

297. Rex DK. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in adults: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. J Fam Pract. 1992; 35:673-81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1453152

298. Hixson LJ, Kelley CL, Jones WN et al. Current trends in the pharmacotherapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Arch Intern Med. 1992; 152:717-23. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1558428

299. Sontag SJ. The medical management of reflux eophagitis: role of antacids and acid inhibition. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1990; 19:683-712. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1977703

300. Richter JE. A critical review of current medical therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986; 8(Suppl 1):72-80. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2874168

301. Antonson CW, Robinson MG, Hawkins TM et al. High doses of histamine antagonists do not prevent relapses of peptic esophagitis following therapy with a proton pump inhibitor. Gastroenterology. 1990; 98:A16.

302. Laheij RJF, Sturkenboom MCJM, Hassing RJ et al. Risk of community-acquired pneumonia and use of gastric acid-suppressive drugs. JAMA. 2004;292:1955-60.

303. Gregor JC. Acid suppression and pneumonia.; a clinical indication for rational prescibing. JAMA. 2004;292:2012-3. Editorial.

304. Fine MJ, Smith MA, Carson MA. Prognosis and outcomes of patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1996; 275:134-41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8531309

HID. Trissel LA. Handbook on injectable drugs. 14th ed. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2007:372-86.

a. GlaxoSmithKline. Tagamet (cimetidine tablets, cimetidine hydrochloride liquid, and cimetidine hydrochloride injection) prescribing information. Research Triangle Park, NC; 2002 June.

b. AHFS drug information 2003. McEvoy GK, ed. Cimetidine. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2003:2775-81.

c. GlaxoSmithKline. Tagamet HB 200 (cimetidine) tablets, product information. In: 2003 PDR for Nonprescription Drugs and Dietary Supplements. Thomson, Montavel NJ; 2003: 659.

Related/similar drugs

Frequently asked questions

More about cimetidine

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (21)

- Drug images

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: H2 antagonists

- Breastfeeding

- En español