Cefixime (Monograph)

Brand name: Suprax

Drug class: Third Generation Cephalosporins

Introduction

Antibacterial; β-lactam antibiotic; third generation cephalosporin.1 2 3 4 6 7 13 23 57 60 75 83

Uses for Cefixime

Urinary Tract Infections

Treatment of adults and pediatric patients ≥6 months of age with uncomplicated UTIs1 2 5 40 51 64 74 75 182 caused by susceptible E. coli1 2 40 51 64 74 75 182 or Proteus mirabilis;1 2 40 51 74 75 182 also has been used for treatment of uncomplicated UTIs caused by susceptible Citrobacter spp.† [off-label],2 51 64 74 C. diversus† [off-label],2 74 C. freundii† [off-label],2 74 Enterobacter spp.† [off-label],2 40 51 E. aerogenes† [off-label],2 40 74 E. agglomerans†,2 64 Klebsiella spp.†,2 40 51 182 K. pneumoniae†,2 64 74 Morganella morganii†,2 Proteus spp.†,2 51 64 or Serratia†.2 51 74

Has been used for treatment of uncomplicated UTIs1 2 5 40 51 64 74 75 182 caused by susceptible gram-positive bacteria, including Staphylococcus epidermidis†,2 Staphylococcus spp.†,2 51 Streptococcus agalactiae†,2 40 nonhemolytic streptococci†,2 40 51 or Enterococcus faecalis†.2 40 Consider that treatment failures have been reported and gram-positive bacteria (e.g., staphylococci, S. agalactiae, enterococci) have been isolated in urine during or after cefixime treatment and usually are resistant to cefixime.2 51 74

Treatment of pyelonephritis† and other complicated UTIs†2 23 40 75 caused by susceptible Enterobacteriaceae, including E. coli.2 23

Otitis Media

Treatment of adults and pediatric patients ≥6 months of age with otitis media1 2 3 5 23 43 56 61 62 63 75 138 164 165 caused by Haemophilus influenzae,1 2 23 61 62 63 Moraxella catarrhalis,1 2 23 61 62 63 or Streptococcus pyogenes (group A β-hemolytic streptococci).1 2 23 62 63 Has also been used for the treatment of otitis media caused by S. pneumoniae; however, overall response was approximately 10% lower for cefixime than for the comparator in clinical studies.1

When anti-infectives indicated, AAP recommends high-dose amoxicillin or amoxicillin and clavulanate as drugs of choice for initial treatment of otitis media; certain cephalosporins (cefdinir, cefpodoxime, cefuroxime, ceftriaxone) recommended as alternatives for initial treatment in penicillin-allergic patients without a history of severe and/or recent penicillin-allergic reactions.184 750 751

Pharyngitis and Tonsillitis

Treatment of adults and pediatric patients ≥6 months of age with pharyngitis and tonsillitis caused by susceptible S. pyogenes (group A β-hemolytic streptococci).1 2 3 5 23 44 56 64 75 Generally effective in eradicating S. pyogenes from nasopharynx; efficacy in prevention of subsequent rheumatic fever not established to date.1

AAP, IDSA, AHA, and others recommend a penicillin regimen (10 days of oral penicillin V or oral amoxicillin or single dose of IM penicillin G benzathine) as treatment of choice for S. pyogenes pharyngitis and tonsillitis;82 86 104 152 750 other anti-infectives (oral cephalosporins, oral macrolides, oral clindamycin) recommended as alternatives in penicillin-allergic patients.82 86 104 152 750

If an oral cephalosporin is used, 10-day regimen of first generation cephalosporin (cefadroxil, cephalexin) is preferred instead of other cephalosporins with broader spectrums of activity (e.g., cefaclor, cefdinir, cefixime, cefpodoxime, cefuroxime).82 86 152 750

Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Bronchitis

Treatment of adults and pediatric patients ≥6 months of age with acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis caused by S. pneumoniae,1 2 23 44 70 72 103 H. influenzae,1 2 23 44 70 72 103 or M. catarrhalis†.2 44 70 72 103

Gonorrhea

Treatment of adults and pediatric patients ≥6 months of age with uncomplicated urethral, endocervical, or rectal infections† caused by susceptible Neisseria gonorrhoeae.1 2 23 48 71 106 108 109 110 111 130 197

Because of concerns related to reports of N. gonorrhoeae with reduced susceptibility to cephalosporins, CDC states that oral cephalosporins no longer recommended as first-line treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhea.130 197 For treatment of uncomplicated urogenital, anorectal, or pharyngeal gonorrhea, CDC recommends a single dose of IM ceftriaxone.130 Add treatment for chlamydia if not excluded.130 746 747 748

Cefixime recommended by CDC as an alternative in patients with urogenital or rectal† gonorrhea when ceftriaxone cannot be used or not available.130 197 Add treatment for chlamydia if not excluded.130 746 747 748

Consider that N. gonorrhoeae with reduced susceptibility to cefixime, including some treatment failures, reported in US and other countries.130 194 195 196 197 198

If infection persists (treatment failure), culture relevant clinical specimens and perform in vitro susceptibility tests.130 197 Also consult infectious disease specialist, STD/HIV Prevention Training Center ([Web]), or CDC (800-232-4636) for treatment advice and report the case to CDC through local or state health departments within 24 hours of diagnosis.130

For all gonorrhea patients, ensure that their sex partners from preceding 60 days are evaluated promptly with culture and receive presumptive treatment with a recommended regimen.130

Pneumonia

Has been used in adults or children for the treatment of mild to moderate pneumonia, including community-acquired pneumonia†.137 166 When used in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia, therapy was initiated with a parenteral third generation cephalosporin (e.g., ceftriaxone, cefotaxime) and then changed to oral cefixime, as appropriate, allowing therapy to be completed on an outpatient basis.137 166

Other cephalosporins (e.g., ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ceftaroline, ceftazidime, cefpodoxime, cefuroxime) are recommended by the American Thoracic Society/IDSA and others when a cephalosporin is used in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia.512 750 751

Lyme Disease

Has been used for treatment of disseminated Lyme disease†.181 Other cephalosporins (cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, cefuroxime axetil) usually recommended by IDSA, AAP, and others when a cephalosporin is used in the treatment of Lyme disease.185 744 745

Shigellosis

Has been used for treatment of shigellosis† caused by susceptible Shigella;139 148 however, other drugs are listed as a first-line or alternative agents in IDSA and AAP guidelines. 217 753

Sinusitis

Has been used for the treatment of mild to moderate sinusitis† caused by S. pneumoniae,2 23 44 70 72 103 H. influenzae2 23 44 70 72 103 M. catarrhalis2 44 70 72 103 137 166 E. coli, H. parahaemolyticus, or H. parainfluenzae2 3 44 75 Because of variable activity against S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae, IDSA no longer recommends second or third generation oral cephalosporins for empiric monotherapy of acute bacterial sinusitis.192 Oral amoxicillin or amoxicillin and clavulanate usually recommended for empiric treatment.192 193 If an oral cephalosporin used as an alternative in children (e.g., in penicillin-allergic individuals), combination regimen that includes a third generation cephalosporin (cefixime or cefpodoxime) and clindamycin (or linezolid) recommended.192 193

Typhoid Fever and Other Salmonella Infections

Has been used in pediatric patients for the treatment of typhoid fever (enteric fever) or septicemia caused by multidrug-resistant strains of Salmonella typhi†.141 142 189 190 191

Multidrug-resistant strains of S.typhi (i.e., strains resistant to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and/or co-trimoxazole) reported with increasing frequency; fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin) and third generation cephalosporins (e.g., ceftriaxone, cefotaxime) have been considered agents of first choice for treatment of typhoid fever or other severe infections known or suspected to be caused by these strains.82 104 146 147 163

Fluoroquinolones no longer recommended as empiric treatment for typhoid fever infections in US.752 766 Ceftriaxone considered a drug of choice for empiric treatment of enteric fever pending results of in vitro susceptibility tests.752 Consider travel history and regional antibiotic resistance patterns when selecting empiric antibiotic therapy for enteric fever;752 765 766 adjust treatment based on results of susceptibility testing.766

Cefixime Dosage and Administration

General

Pretreatment Screening

-

Prior to initiation of therapy, careful inquiry should be made concerning previous hypersensitivity reactions to cephalosporins, penicillins, other β-lactam anti-infectives, or other drugs.1

Patient Monitoring

-

Monitor patients for hypersensitivity reactions.1 If a severe hypersensitivity reaction occurs, immediately discontinue cefixime and institute appropriate therapy as indicated.1

-

Carefully monitor patients receiving dialysis during treatment with cefixime.1

-

Monitor prothrombin time in patients with impaired vitamin K synthesis or low vitamin K stores (e.g., chronic hepatic disease, malnutrition).1 Administer vitamin K when indicated.1

Other General Considerations

-

To reduce the development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain effectiveness of cefixime and other antibacterials, use cefixime only for treatment or prevention of infections proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria.1

Administration

Oral Administration

Administer orally as capsules, conventional tablets, chewable tablets, or oral suspension.1

Capsules and conventional tablets: Administer without regard to meals.1

Chewable tablets: Must be chewed or crushed before swallowing.1

Reconstitution

Reconstitute oral suspension at the time of dispensing by adding amount of water specified on the container in 2 equal portions; shake after each addition.1 The reconstituted suspension contains 100, 200, or 500 mg/5 mL.1

Shake oral suspension well just prior to administration of each dose.1

Dosage

Available as cefixime trihydrate; dosage expressed in terms of cefixime.1

Capsules containing 400 mg of cefixime are bioequivalent to conventional 400-mg tablets when administered under fasting conditions.1

Chewable tablets are bioequivalent to oral suspension.1

Conventional tablets and oral suspension are not bioequivalent.1

Pediatric Patients

General Pediatric Dosage

Oral

Children beyond neonatal period: AAP recommends 8 mg/kg daily in 1 or 2 equally divided doses for treatment of mild or moderate infections.82 757 AAP states the drug is inappropriate for treatment of severe infections.82

Children weighing 5–7.5 kg: Oral suspension containing 100 mg/5 mL is preferred preparation.1

Children weighing 7.6–10 kg: Oral suspension containing 100 or 200 mg/5 mL is preferred preparation.1

Children weighing <10 kg: Chewable tablets not recommended.1

Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

Uncomplicated UTIs

OralChildren 6 months to 12 years of age: 8 mg/kg once daily or 4 mg/kg every 12 hours1 for 5–10 days.2 40 51 74

Children >12 years of age or weighing >45 kg: 400 mg once daily or 200 mg every 12 hours1 for 5–10 days.2 40 51 74

Otitis Media

Oral

Children 6 months to 12 years of age: 8 mg/kg once daily or 4 mg/kg every 12 hours1 for 10–14 days.23 56 62 63

Children >12 years of age or weighing >45 kg: 400 mg daily1 for 10–14 days.44 64 72

Do not use capsules or conventional tablets for treatment of otitis media.1

Pharyngitis and Tonsillitis

Oral

Children 6 months to 12 years of age: 8 mg/kg once daily or 4 mg/kg every 12 hours for ≥10 days.1

Children >12 years of age or weighing >45 kg: 400 mg once daily or 200 mg every 12 hours1 for ≥10 days.44 64 72

Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Bronchitis

Oral

Children 6 months to 12 years of age: 8 mg/kg once daily or 4 mg/kg every 12 hours1 for 10–14 days.44 64 72

Children >12 years of age or weighing >45 kg: 400 mg once daily or 200 mg every 12 hours1 for 10–14 days.44 64 72

Gonorrhea and Associated Infections

Uncomplicated Urethral, Endocervical, or Rectal† Gonorrhea

OralIn pediatric patients or adolescents weighing ≥45 kg when ceftriaxone is unavailable or cannot be used, CDC and AAP recommend a single oral cefixime dose of 800 mg.130 748

Prepubertal children ≥6 months of age weighing <45 kg: 8 mg/kg recommended by manufacturer.1

Children ≥12 years of age or weighing ≥45 kg: 400 mg as a single dose recommended by manufacturer.1

Not recommended by CDC as first-line treatment.130 197 If chlamydia not excluded, also treat patient for chlamydia.130 748

Shigellosis†

Oral

8 mg/kg daily for 5 days.139 148

Acute Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis†

Oral

8 mg/kg daily in 2 equally divided doses for 10–14 days.192

Typhoid Fever†

Oral

Children 6 months to 16 years of age: 5–10 mg/kg twice daily.141 142 189 190 191 Usually given for 14 days;141 142 189 high rate of treatment failure occurred when given for only 7 days.190

Adults

Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

Uncomplicated UTIs

Oral400 mg once daily or 200 mg every 12 hours1 for 5–10 days.40 51 74

Otitis Media

Oral

400 mg once daily or 200 mg every 12 hours1 for 10–14 days.23 56 62 63

Do not use capsules or conventional tablets for treatment of otitis media.1

Pharyngitis and Tonsillitis

Oral

400 mg once daily or 200 mg every 12 hours for ≥10 days.1

Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Bronchitis

Oral

400 mg once daily or 200 mg every 12 hours1 for 10–14 days.44 64 72

Gonorrhea and Associated Infections

Uncomplicated Urethral, Endocervical, or Rectal† Gonorrhea

Oral800 mg as a single dose recommended by CDC as alternative when ceftriaxone unavailable or cannot be used.130

Use in conjunction with treatment for chlamydia if chlamydia not ruled out.130 Not recommended by CDC as first-line treatment.130 197

Manufacturer recommends a single 400-mg dose of cefixime for treatment of uncomplicated cervical/urethral gonococcal infections.1

Lyme Disease†

Oral

200 mg daily for 100 days (administered with oral probenecid).181

Special Populations

Renal Impairment

Dosage adjustments necessary in patients with Clcr <60 mL/minute.1 2 Adults with Clcr 21–59 mL/minute: 260 mg daily as oral suspension, preferably as oral suspension containing 200 or 500 mg/5 mL; conventional tablets and chewable tablets not recommended.1

Adults with Clcr ≤20 mL/minute: 200 mg daily as conventional tablets or chewable tablets, 172 mg daily as oral suspension containing 100 mg/5 mL, 176 mg daily as oral suspension containing 200 mg/5 mL, or 180 mg daily as oral suspension containing 500 mg/5 mL.1

Adults undergoing hemodialysis: 260 mg daily as oral suspension, preferably as oral suspension containing 200 or 500 mg/5 mL; conventional tablets and chewable tablets not recommended.1

Adults undergoing continuous peritoneal dialysis: 200 mg daily as conventional tablets or chewable tablets, 172 mg daily as oral suspension containing 100 mg/5 mL, 176 mg daily as oral suspension containing 200 mg/5 mL, or 180 mg daily as oral suspension containing 500 mg/5 mL.1

Hepatic Impairment

The manufacturer makes no specific dosage recommendations for patients with hepatic impairment.1

Geriatric Patients

No dosage adjustments except those related to renal impairment.2 35 37

Cautions for Cefixime

Contraindications

-

Known hypersensitivity to cefixime or other cephalosporins.1

Warnings/Precautions

Hypersensitivity Reactions

Hypersensitivity reactions such as anaphylaxis (including shock and fatalities), angioedema, serum sickness-like reactions, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis have been reported.1 5 40 41 43 56 64 75

If an allergic reaction occurs, discontinue cefixime.1

Partial cross-allergenicity among cephalosporins and other β-lactam antibiotics, including penicillins and cephamycins.1 172 173 Use caution.1

Prior to initiation of therapy, make careful inquiry concerning previous hypersensitivity reactions to cephalosporins, penicillins, or other drugs.1 Cefixime is contraindicated in individuals hypersensitive to cephalosporins.1 Avoid use in those who have had an immediate-type (anaphylactic) hypersensitivity reaction and administer with caution in those who have had a delayed-type (e.g., rash, fever, eosinophilia) reaction.173

Clostridioides difficile-associated Diarrhea

Treatment with anti-infectives alters normal colon flora and may permit overgrowth of Clostridioides difficile.1 42 177 178 C. difficile infection (CDI) and C. difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis (CDAD; also known as antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis or pseudomembranous colitis) reported with nearly all anti-infectives, including cefixime, and may range in severity from mild diarrhea to fatal colitis.1 42 177 178 C. difficile produces toxins A and B which contribute to development of CDAD;1 40 42 hypertoxin-producing strains of C. difficile are associated with increased morbidity and mortality since they may be refractory to anti-infectives and colectomy may be required.1

Consider CDAD if diarrhea develops during or after therapy and manage accordingly.1 42 177 178 Obtain careful medical history since CDAD may occur as late as 2 months or longer after anti-infective therapy is discontinued.42

If CDAD is suspected or confirmed, discontinue anti-infectives not directed against C. difficile whenever possible.42 177 178 Initiate appropriate supportive therapy (e.g., fluid and electrolyte management, protein supplementation), anti-infective therapy directed against C. difficile (e.g., metronidazole, vancomycin), and surgical evaluation as clinically indicated.1 42 177 178

Dose Adjustment in Renal Impairment

Serum concentrations of cefixime higher and more prolonged in patients with moderate or severe renal impairment than in patients with normal renal function; decrease dose and/or frequency of administration of cefixime in patients with impaired renal function, including those undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) or hemodialysis.2 23 33 37 75 Carefully monitor patients undergoing dialysis during cefixime therapy.1

Coagulation Effects

Patients with renal or hepatic impairment, poor nutritional status, prolonged anti-infective therapy, and previous anticoagulant therapy (stabilized) appear to be at risk.1 Monitor PT in such patients and administer exogenous vitamin K as indicated.1

Development of Drug-resistant Bacteria

To reduce development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain effectiveness of cefixime and other antibacterials, the drug should be used only for the treatment or prevention of infections proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria.1 When selecting or modifying anti-infective therapy, results of culture and in vitro susceptibility testing should be used.1 In the absence of such data, consider local epidemiology and susceptibility patterns when selecting anti-infectives for empiric therapy.1

Patients with Phenylketonuria

Chewable tablets containing 100, 150, and 200 mg of cefixime contain aspartame , which is metabolized in the GI tract to provide 3.3, 5, and 6.7 mg of phenylalanine, respectively.1 Phenylalanine can be harmful to patients with phenylketonuria; consider combined daily amount of phenylalanine from all sources before prescribing cefixime chewable tablets in such patients.1

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

No adequate and controlled studies to date using cefixime in pregnant women; use drug during pregnancy only when clearly needed.1 Use of drug during labor and delivery also not studied to date; use in these circumstances only when clearly needed.1

Lactation

Distributed into milk in rats;36 not known whether distributed into milk in humans.1 Discontinue nursing or the drug.1

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy not established in children <6 months of age.1 Frequency of adverse GI effects (e.g., diarrhea, loose stools) similar to that in adults.1

Geriatric Use

Insufficient experience in patients ≥65 years of age to determine whether geriatric patients respond differently than younger adults.1

Possible increased oral bioavailability;1 35 37 not considered clinically important.35 37

Consider age-related decreases in renal function when selecting dosage and adjust dosage if necessary.2 35 37

Hepatic Impairment

There is no evidence of metabolism of cefixime in vivo.1 Hepatic impairment is not expected to affect clearance of cefixime.1

Renal Impairment

Increased serum half-life in patients with moderate or severe renal impairment.1 2 23 33 37 75 Dosage adjustments necessary if Clcr <60 mL/minute.1 2 33 35 37

Common Adverse Effects

Diarrhea (16%), nausea (7%), loose stools (6%), abdominal pain (3%), dyspepsia (3%), vomiting.1

Drug Interactions

Specific Drugs and Laboratory Tests

|

Drug or Test |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Antacids (aluminum- or magnesium-containing) |

No clinically important effect on cefixime pharmacokinetics 32 |

|

|

Anticoagulants, oral (warfarin) |

Possible increased PT (with or without bleeding)1 |

|

|

Carbamazepine |

Increased carbamazepine concentrations1 |

Monitor carbamazepine concentrations1 |

|

Coomb's test |

Possible false positive Coomb's test results with cephalosporins1 |

|

|

Nifedipine |

Possible increased plasma concentrations and AUC of cefixime143 |

|

|

Probenecid |

Increased cefixime plasma concentrations and AUC2 |

|

|

Salicylates |

Possible decreased plasma concentrations and AUC of cefixime2 25 |

|

|

Tests for glucose |

Possible false-positive reactions in urine glucose tests using Clinitest, Benedict’s solution, or Fehling’s solution1 |

Use glucose tests based on enzymatic glucose oxidase reactions (e.g., Clinistix, Tes-Tape)1 |

|

Tests for ketones |

Possible false-positive reaction for ketones in urine if nitroprusside tests used; not reported with tests using nitroferricyanide1 |

Cefixime Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

30–50% of a single oral dose absorbed;1 2 5 75 100 peak serum concentrations attained within 2–6 hours.1 2 26 30 31 35 37 100

Capsules containing 400 mg of cefixime are bioequivalent to conventional tablets containing 400 mg of the drug when administered under fasting conditions.1

Chewable tablets are bioequivalent to the oral suspension.1

Conventional tablets and oral suspension are not bioequivalent;1 studies in adults indicate oral suspension results in peak serum concentrations and AUC 25–50% and 10–25% higher, respectively, than those attained with tablets.1

Food

Conventional tablets and oral suspension: Food decreases rate1 but not extent of absorption.1 2 3 26

Capsules: Food decreases absorption by about 15% (based on AUC) or 25% (based on peak serum concentrations).1

Distribution

Extent

Distributed into bile,1 2 5 sputum,2 23 tonsils,23 maxillary sinus mucosa,23 middle ear discharge,23 blister fluid,2 75 and prostatic fluid.2

Distribution into CSF unknown.1

Crosses the placenta.2 23 Not detected in human milk following a single 100-mg oral dose.2

Plasma Protein Binding

Elimination

Metabolism

Does not appear to be metabolized; no biologically active metabolites detected in serum or urine.1 2 5 23 30

Elimination Route

Eliminated by renal and nonrenal mechanisms.1 2 23 24 26 27 29 30 31 37 52 75

7–50% of a dose excreted unchanged in urine within 24 hours.1 2 23 24 26 27 29 31 37 75 100 In animal studies, >10% of a dose may be excreted unchanged in bile.1 2 52

Not substantially removed by hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.1 2 33 37 75

Half-life

Adults with normal renal function: 2.4–4 hours.1 2 5 23 24 26 27 29 31 33 37 75 100

Special Populations

Adults with moderate renal impairment (Clcr 20–40 mL/minute): Serum half-life averages 6.4 hours.1

Adults with severe renal impairment (Clcr 5–20 mL/minute): Serum half-life averages 11.5 hours.1

Geriatric patients: AUC at steady state approximately 40% higher than in younger adults; not considered clinically important.1

Stability

Storage

Oral

Capsules, Conventional Tablets, Chewable Tablets

20–25°C.1

For Suspension

20–25°C.1 After reconstitution, store suspension in tight container at room temperature or in the refrigerator; discard after 14 days.1

Actions and Spectrum

-

Based on spectrum of activity, classified as a third generation cephalosporin.3 13 15 50 69 75 Expanded spectrum of activity against gram-negative bacteria compared with first and second generation cephalosporins;2 3 5 14 23 59 60 75 less active against Enterobacteriaceae than some other third-generation cephalosporins.15 75 101

-

Like other β-lactam antibiotics, antibacterial activity results from inhibition of bacterial cell wall synthesis.1 2 75

-

Spectrum of activity includes many gram-positive and gram-negative aerobic bacteria;1 inactive against most anaerobic bacteria.2 14 23 59 60 75

-

Gram-positive aerobes: Active in vitro against Streptococcus pneumoniae1 and Streptococcus pyogenes (group A β-hemolytic streptococci).1 2 3 13 14 20 23 50 59 60 66 77 78 79 Also active in vitro against S. agalactiae (group B streptococci)1 2 13 15 18 23 50 59 60 66 75 and groups C, F, and G streptococci.13 23 59 60 66 Most staphylococci, enterococci, and Listeria monocytogenes are resistant.1 2 3 13 14 18 20 23 59 60 66 69 75 78 101

-

Strains of staphylococci resistant to penicillinase-resistant penicillins (methicillin-resistant [oxacillin-resistant] staphylococci) should be considered resistant to cefixime, although results of in vitro susceptibility tests may indicate susceptibility.132

-

Gram-negative aerobes: Active in vitro against Neisseria gonorrhoeae,1 2 3 5 11 14 23 59 60 75 Haemophilus influenzae (including β-lactamase-producing strains),1 2 3 5 8 10 13 14 18 20 23 50 59 65 66 68 75 76 77 78 Moraxella catarrhalis (including β-lactamase-producing strains),1 2 3 5 13 20 23 58 59 66 75 77 78 Escherichia coli,1 and Proteus mirabilis.1 15 21 23 59 60 75 Also active in vitro against Citrobacter amalonaticus,1 C. diversus,1 H. parainfluenzae,1 2 8 13 Klebsiella,1 Pasteurella multocida,1 P. vulgaris,1 Providencia,1 Salmonella,1 Shigella,1 and Serratia.1 Most Enterobacter5 60 75 and Pseudomonas are resistant.1 2 5 13 14 15 20 23 59 60 66 75 101

Advice to Patients

-

Advise patients that antibacterials (including cefixime) should only be used to treat bacterial infections and not used to treat viral infections (e.g., the common cold).1

-

Importance of completing full course of therapy, even if feeling better after a few days.1

-

Advise patients that skipping doses or not completing the full course of therapy may decrease effectiveness and increase the likelihood that bacteria will develop resistance and will not be treatable with cefixime or other antibacterials in the future.1

-

Advise patients that diarrhea is a common problem caused by anti-infectives and usually ends when the drug is discontinued.1 Importance of contacting a clinician if watery and bloody stools (with or without stomach cramps and fever) occur during or as late as 2 months or longer after the last dose.1

-

Importance of discontinuing cefixime and informing clinician if an allergic reaction occurs.1

-

Advise patients with phenylketonuria that cefixime chewable tablets containing 100, 150, and 200 mg of the drug contain aspartame, which is metabolized in the GI tract to provide 3.3, 5, and 6.7 mg of phenylalanine, respectively.1

-

Importance of women informing clinician if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1

-

Importance of informing clinicians of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs.1

-

Importance of informing patients of other important precautionary information.1

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer’s labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

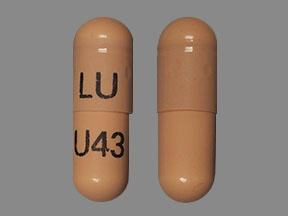

Oral |

Capsules |

400 mg (of cefixime) |

Suprax |

Lupin |

|

For suspension |

100 mg (of cefixime) per 5 mL |

Suprax |

Lupin |

|

|

200 mg (of cefixime) per 5 mL |

Suprax |

Lupin |

||

|

500 mg (of cefixime) per 5 mL |

Suprax |

Lupin |

||

|

Tablets, chewable |

100 mg (of cefixime) |

Suprax |

Lupin |

|

|

150 mg (of cefixime) |

Suprax |

Lupin |

||

|

200 mg (of cefixime) |

Suprax |

Lupin |

||

|

Tablets, film-coated |

400 mg (of cefixime) |

Suprax (scored) |

Lupin |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions July 10, 2025. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

1. Lupin Pharma. Suprax (cefixime) tablets, capsules, chewable tablets, and powder for oral suspension prescribing information. Baltimore, MD; 2018 Mar.

2. Lederle. Suprax (cefixime) product monograph. Pearl River, NY; 1989 Jun.

3. Smith GH. Oral cephalosporins in perspective. DICP. 1990; 24:45-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2405586

4. Inamoto Y, Chiba T, Kamimura T et al. FK 482, a new orally active cephalosporin: synthesis and biological properties. J Antibiot. 1988; 41:828-30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3255303

5. Cooper RJ, Hoffman JR, Bartlett JG et al. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute pharyngitis in adults: background. Ann Intern Med. 2001; 134:509-17. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11255530

6. Knoller J, Schonfeld W, Bremm KD et al. In vitro stability of cefixime (FK-027) in serum, urine and buffer. J Chromatogr. 1987; 389:312-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3571358

7. Namiki Y, Tanabe T, Kobayashi T et al. Degradation kinetics and mechanisms of a new cephalosporin, cefixime, in aqueous solution. J Pharm Sci. 1987; 76:208-14. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3585736

8. Kumar A. In vitro activity of cefixime (CL284635) and other antimicrobial agents against Haemophilus isolates from pediatric patients. Chemotherapy. 1988; 34:30-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3258232

9. Smith SM. Activity of cefixime (FK 027) for resistant gram-negative bacilli. Chemotherapy. 1988; 34:455-61. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3243091

10. Powell M. In vitro susceptibility of Haemophilus influenzae to cefixime. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987; 31:1841-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3501703

11. Bowie WR, Shaw CE, Chan DGW et al. In vitro activity of difloxacin hydrochloride (A-56619), A-56620, and cefixime (CL 284,635; FK 027) against selected genital pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986; 30:590-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3098163

12. Noel GJ. In vitro activities of selected new and long-lasting cephalosporins against Pasteurella multocida . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986; 29:344-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3087279

13. Neu HC, Chin NX. Comparative in vitro activity and β-lactamase stability of FR 17027, a new orally active cephalosporin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984; 26:174-80. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6333207

14. Kamimura T, Kojo H, Matsumoto Y et al. In vitro and in vivo antibacterial properties of FK 027, a new orally active cephem antibiotic. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984; 25:98-104. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6561017

15. Fuchs PC, Jones RN, Barry AL et al. In vitro evaluation of cefixime (FK027, FR17027, CL284635): spectrum against recent clinical isolates, comparative antimicrobial activity, β-lactamase stability, and preliminary susceptibility testing criteria. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1986; 5:151-62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3522088

17. Jorgensen JH, Doern GV, Thornsberry C et al. Susceptibility of multiply resistant Haemophilus influenzae to newer antimicrob agents. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1988; 9:27-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3259490

18. Cullmann W, Dick W, Stieglitz M et al. Comparative evaluation of orally active beta-lactam compounds in ampicillin-resistant gram-positive and gram-negative rods: role of beta lactamases on resistance. Chemotherapy. 1988; 34:202-15. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3262045

19. Counts GW, Baugher LK, Ulness BK et al. Comparative in vitro activity of the new oral cephalosporin cefixime. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1988; 7:428-31. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3137053

20. Knapp CC, Sierra-Madero J. Antibacterial activities of cefpodoxime, cefixime, and ceftriaxone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988; 32:1896-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3245701

21. Sanders CC. β-lactamase stability and in vitro activity of oral cephalosporins against strains possessing well-characterized mechanisms of resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989; 33:1313-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2802558

22. Garcia-Rodriguez JA, Garcia Sanchez JE, Garcia Garcia MI et al. In vitro activities of new oral β-lactams and macrolides against Campylobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother.1989; 33:1650-1.

23. Brogden RN. Cefixime: a review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic potential. Drugs. 1989; 38:524-50. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2684593

24. Faulkner RD, Sia LL, Barone JS et al. Bioequivalency of oral suspension formulations of cefixime. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1989; 10: 205-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2706319

25. Bialer M, Wu WH, Faulkner RD et al. In vitro protein binding interaction studies involving cefixime. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1988; 9:315-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3395672

26. Faulkner RD, Bohaychuk W, Haynes JD et al. The pharmacokinetics of cefixime in the fasted and fed state. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1988; 34: 5225-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3203716

27. Faulkner RD, Fernandez P, Lawrence G et al. Absolute bioavailability of cefixime in man. J Clin Pharmacol. 1988; 28:700-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3216036

29. Faulkner RD, Bohaychuk W, Desjardins RE et al. Pharmacokinetics of cefixime after once-a-day and twice-a-day dosing to steady state. J Clin Pharmacol. 1987; 27:807-12. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3429686

30. Nakashima M, Uematsu T, Takiguchi Y et al. Phase I study of cefixime, a new oral cephalosporin. J Clin Pharmacol. 1987; 27:425-31. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3693588

31. Brittain DC, Scully BE, Hirose T et al. The pharmacokinetic and bactericidal characteristics of oral cefixime. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1985; 38:590-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4053491

32. Healy DP, Sahai JV, Sterling LP et al. Influence of an antacid containing aluminum and magnesium on the pharmacokinetics of cefixime. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989; 33: 1994-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2610509

33. Guay DRP, Meatherall RC, Harding GK et al. Pharmacokinetics of cefixime (CL 284,635; FK 027) in healthy subjects and patients with renal insufficiency. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986; 30:485-90. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3777912

34. Bergeron MG. Penetration of cefixime into fibrin clots and in vivo efficacy against Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986; 30:913-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3545070

35. Faulkner RD, Bohaychuk W, Lanc RA et al. Pharmacokinetics of cefixime in the young and elderly. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988; 21:787-94. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3410802

36. Halperin-Walega E, Batra VK, Tonelli AP et al. Disposition of cefixime in the pregnant and lactating rat: transfer to the fetus and nursing pup. Drug Metab Dispos. 1988; 16:130-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2894941

37. Faulkner RD, Yacobi A, Barone JS et al. Pharmacokinetic profile of cefixime in man. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1987; 6:963-70.

39. Finegold SM, Ingram-Drake L, Gee R et al. Bowel flora changes in humans receiving cefixime (CL 284,635) or cefaclor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987; 31:443-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3579262

40. Iravani A, Richard GA, Johnson D et al. A double-blind, multicenter, comparative study of the safety and efficacy of cefixime versus amoxicillin in the treatment of acute urinary tract infections in adult patients. Am J Med. 1988; 85(Suppl 3A):17-23. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3048090

41. Tally FP, Desjardins RE, McCarthy EF et al. Safety profile of cefixime. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1987; 6:976-80.

42. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010; 31:431-55. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20307191

43. Leigh AP, Robinson D. A general practice comparative study of a new third-generation oral cephalosporin, cefixime, with amoxycillin in the treatment of acute paediatric otitis media. Br J Clin Pract. 1989; 43:140-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2686744

44. Kiani R, Johnson D. Comparative multicenter studies of cefixime and amoxicillin in the treatment of respiratory tract infections. Am J Med. 1988; 85(Suppl 3A):6-13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3048092

48. Megran DW, Lefebvre K, Willetts V et al. Single-dose oral cefixime versus amoxicillin plus probenecid for the treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea in men. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990; 34:355-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2183719

50. Krepel CJ, Schopf LR, Gordon RC et al. Comparative in vitro activity of cefixime with eight other antimicrobials against Enterobacteriaceae, streptococci, and Haemophilus influenzae . Curr Ther Res. 1988; 43:296-302.

51. Levenstein J, Summerfield PJF, Fourie S et al. Comparison of cefixime and co-trimoxazole in acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection: a double-blind general practice study. S Afr Med J. 1986; 70:455-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3535127

52. Yamanaka H, Chiba T, Kawabata K et al. Studies on β-lactam antibiotics: IX. Synthesis and biological activity of a new orally active cephalosporin, cefixime (FK027). J Antibiot. 1985; 38:1738-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4093334

54. Dance DAB, Wuthiekanun V, Chaowagul W et al. The antimicrobial susceptibility of Pseudomonas pseudomallei: emergence of resistance in vitro and during treatment. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989; 24:295-309. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2681116

56. Scott HV, Pannowitz D. Cefixime: clinical trial against otitis media and tonsillitis. N Z Med J. 1990; 103:25-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2406651

57. Neu HC. β-Lactam antibiotics: structural relationships affecting in vitro activity and pharmacologic properties. Clin Infect Dis. 1986; 8(Suppl 3):S237-60.

58. Saito A, Yamaguchi K, Shigeno Y et al. Clinical and bacteriological evaluation of Branhamella catarrhalis in respiratory infections. Drugs. 1986; 31(Suppl 3):87-92. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3488201

59. Barry AL. Cefixime: spectrum of antibacterial activity against 16016 clinical isolates. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1987; 6: 954-7.

60. Neu HC. In vitro activity of a new broad spectrum, beta-lactamase-stable oral cephalosporin, cefixime. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1987; 6:958-62.

61. Howie VM. Bacteriologic and clinical efficacy of cefixime compared with amoxicillin in acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1987; 6:989-91.

62. Kenna MA, Bluestone CD, Fall P et al. Cefixime vs. cefaclor in the treatment of acute otitis media in infants and children. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1987; 6:992-6.

63. McLinn SE. Randomized, open label, multicenter trial of cefixime compared with amoxicillin for treatment of acute otitis media with effusion. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1987; 6:997-1001.

64. Risser WL, Barone JS, Clark PA et al. Noncomparative, open label, multicenter trial of cefixime for treatment of bacterial pharyngitis, cystitis and pneumonia in pediatric patients. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1987; 6:1002-6.

65. Mendelman PM, Henritzy LL, Chaffin DO et al. In vitro activities and targets of three cephem antibiotics against Haemophilus influenzae . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989; 33:1878-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2610499

66. Neu HC, Saha G. Comparative in vitro activity and β-lactamase stability of FK482, a new oral cephalosporin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989; 33:1795-800. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2589845

67. Nord CE, Movin G. Impact of cefixime on the normal intestinal microflora. Scand J Infect Dis. 1988; 20:547-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3222669

68. Machka K, Balg H, Braveny I. In vitro activity of new antibiotics against Haemophilus influenzae . Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1988; 7:812-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3145871

69. Nies BA. Comparative activity of cefixime and cefaclor in an in vitro model simulating human pharmacokinetics. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1989; 8:558-61.

70. Beumer HM. Cefixime versus amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in lower respiratory tract infections. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1989; 27:30-3.

71. Kuhlwein A. Efficacy and safety of a single 400 mg oral dose of cefixime in the treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989; 8:261-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2496996

72. Dorow P. Safety and efficacy of cefixime versus cefaclor in respiratory tract infections. J Chemother. 1989; 1:257-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2809693

74. Cox CE. Cefixime versus trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole in treatment of patients with acute, uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections. Urology. 1989; 43:322-6.

75. Leggett NJ, Caravaggio C. Cefixime. DICP. 1990; 24:489-95. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2188437

76. Mortensen JE. Comparative in vitro activity of cefixime against Haemophilus influenzae isolates, including ampicillin-resistant, non-β-lactamase-producing isolates, from pediatric patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990; 34:1456-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2386375

77. Liebowitz LD, Saunders J. In vitro susceptibility of upper respiratory tract pathogens to 13 oral antimicrobial agents. S Afr Med J. 1987; 72:385-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3660122

78. Matsui H, Hiraoka M, Inoue M et al. Antimicrobial activity and stability to β-lactmase of BMY-28271, a new oral cephalosporin ester. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990; 34:555-61. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2344162

79. Jacoby GA. Activities of β-lactam antibiotics against Escherichia coli strains producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990; 34:858-62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2193623

81. Hoppe JE. In vitro susceptibilities of Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis to six new oral cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990; 34:1442-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2386374

82. American Academy of Pediatrics. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012.

83. Food and Drug Administration. Antibiotic drugs; cefixime trihydrate; cefixime trihydrate tablets and cefixime trihydrate powder for oral suspension. (Docket No. 88N-0121). Fed Regist. 1988; 53:24256-9.

86. Gerber MA, Baltimore RS, Eaton CB et al. Prevention of rheumatic fever and diagnosis and treatment of acute Streptococcal pharyngitis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the Interdisciplinary Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology, and the Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2009; 119:1541-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19246689

100. Kees F, Naber KG, Sigl G et al. Relative bioavailability of three cefixime formulations. Arzneimittelforschung. 1990; 40:293-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2346538

101. Anon. Choice of cephalosporins. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1990; 32:107-10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2243553

102. Reviewers’ comments (personal observations).

103. Verghese A, Roberson B, Kalbfleisch JH et al. Randomized comparative study of cefixime versus cephalexin in acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990; 34:1041-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2118322

104. Anon. Drugs for bacterial infections. Med Lett Treat Guid. 2010; 8:43-52.

106. Handsfield HH, McCormack WM, Hook EW et al. A comparison of single-dose cefixime with ceftriaxone as treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhea. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:1337-41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1922235

108. Plourde PJ, Tyndall M, Agoki E et al. Single-dose cefixime versus single-dose ceftriaxone in the treatment of antimicrobial-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection. J Infect Dis. 1992; 166:919-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1527431

109. Anon. Interim guidelines for the treatment of uncomplicated gonococcal infection. CMAJ. 1992; 146:1587-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1571870

110. Cates W Jr. Sexually transmitted diseases in the 1990’s. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:368-9.

111. Cates W Jr. Commentary on “Cefixime or ceftriaxone for gonorrhea?” ACP J Club. 1992; March-April:52. (Ann Intern Med. vol 116, suppl 2). Comment on Handsfield HH, McCormack WM, Hook EW III, et al. A comparison of single-dose cefixime with ceftriaxone as treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhea. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:1337-41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1922235

114. Tatsuta M, Ishikawa H, Iishi H et al. Reduction of gastric ulcer recurrence after suppression of Helicobacter pylori by cefixime. Gut. 1990; 31:973-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2210464

115. Westblom TU, Gudipati S. In vitro susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori to the new oral cephalosporins cefpodoxime, ceftibuten and cefixime. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990; 9:691-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2226500

118. Portilla I, Lutz B, Montalvo M et al. Oral cefixime versus intramuscular ceftriaxone in patients with uncomplicated gonococcal infections. Sex Transm Dis. 1992; 19:94-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1534422

119. Dunnett DM. Cefixime in the treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea. Sex Transm Dis. 1992; 19:92-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1595018

120. Asbach HW. Single dose oral administration of cefixime 400 mg in the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and gonorrhoea. Drugs. 1991; 42(Suppl 4):10-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1725148

121. Loo VG, Sherman P. Helicobacter pylori infection in a pediatric population: in vitro susceptibilities to omeprazole and eight antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992; 36:1133-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1510406

122. Ateshkadi A, Lam NP. Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease. Clin Pharm. 1993; 12:34-48. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8428432

123. Millar MR. Bactericidal activity of antimicrobial agents against slowly growing H. pylori . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992; 36:185-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1590687

130. Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021; 70:1-187.. . ;

132. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: Twenty-first informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S21. Wayne, PA; 2011.

137. Markham A. Cefixime: a review of its therapeutic efficacy in lower respiratory tract infections. Drugs. 1995; 49:1007-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7641600

138. Gooch WM, Philips A, Rhoades R et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety and acceptability of cefixime and amoxicillin/clavulanate in acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997; 16:S21-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9041624

139. Ashkenazi S, Amir J, Waisman Y et al. A randomized, double-blind study comparing cefixime and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of childhood shigellosis. J Pediatr. 1993; 123:817-21. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8229498

140. Salam MA, Seas C, Khan WA et al. Treatment of shigellosis: cefixime is ineffective in shigellosis in adults. Ann Intern Med. 1995; 123:505-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7661494

141. Bhutta ZA, Khan IA. Therapy of multidrug-resistant typhoid fever with oral cefixime vs. intravenous ceftriaxone. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994; 13:990-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7845753

142. Girgis NI, Sultan Y, Hammad O et al. Comparison of the efficacy, safety and cost of cefixime, ceftriaxone and aztreonam in the treatment of multidrug-resistant Salmonella typhi septicemia in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995; 14:603-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7567290

143. Duverne C, Bouten A, Deslandes A et al. Modification of cefixime bioavailability by nefedipine in humans: involvement of the dipeptide carrier system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992; 36:2462-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1489189

144. Gremse DA, Dean PC, Farquhar DS et al. Cefixime and antibiotic-associated colitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994; 13:331-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8036057

146. Soe GB. Treatment of typhoid fever and other systemic salmonelloses with cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, cefoperazone, and other newer cephalosporins. Rev Infect Dis. 1987; 9:719-36. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3125577

147. Mermin JH, Townes JM, Gerber M et al. Typhoid fever in the United States, 1985-1994: changing risks of international travel and increasing antimicrobial resistance. Arch Intern Med. 1998; 158:633-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9521228

148. Helvaci M, Bektaslar D, Ozkaya B et al. Comparative efficacy of cefixime and ampicillin-sulbactam in shigellosis in children. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1998; 40:131-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9581302

149. Asmar BI, Dajani AS, Del Beccaro MA et al. Comparison of cefpodoxime proxetil and cefixime in the treatment of acute otitis media in infants and children. Pediatrics. 1994; 94:847-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7971000

150. Rodriguez WJ, Khan W, Sait T et al. Cefixime vs. cefaclor in the treatment of acute otitis media in children: a randomized, comparative study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993; 12:70-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8417429

152. Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012; 55:1279-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23091044

154. Pichichero ME. Shortened course of antibiotic therapy for acute otitis media, sinusitis and tonsillopharyngitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997; 16:680-95. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9239773

156. Pichichero ME. Cephalosporins are superior to penicillin for treatment of streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis: is the difference worth it? Pediatr Infect Dis. 1993; 12:268-74.

161. Block SL, Hedrick JA. Comparative study of the effectiveness of cefixime and penicillin V for the treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis in children and adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992; 11:919-25. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1454432

162. Friedland IR. Cefixime therapy for otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993; 12:544-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8345993

163. Nataro JP. Treatment of bacterial enteritis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998; 17:420-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9613658

164. Bluestone CD. Review of cefixime in the treatment of otitis media in infants and children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993; 12:75-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8417430

165. Owen MJ, Anwar R, Nguyen HK et al. Efficacy of cefixime in the treatment of acute otitis media in children. Am J Dis Child. 1993; 147:81-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8418608

166. Ramirez JA, Srinath L, Ahkee S et al. Early switch from intravenous to oral cephalosporins in the treatment of hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 1995; 155:1273-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7778957

167. Spangler SK, Jacobs MR. In vitro susceptibilities of 185 penicillin-susceptible and - resistant pneumococci to WY-49605 (SUN/SY 555%), a new oral penem, compared with those to penicillin G, amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, cefixime, cefaclor, cefpodoxime, cefuroxime, and cefdinir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994; 38:2902-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7695280

168. Thorburn CE, Knott SJ. In vitro activities of oral β-lactams at concentrations achieved in humans against penicillin-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci and potential to select resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998; 42:1973-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9687392

169. Davies HD, Low DE, Schwartz B et al. Evaluation of short-course therapy with cefixime or rifampin for eradication of pharyngeally carried group A streptococci. Clin Infect Dis. 1995; 21:1294-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8589159

170. Ottolini M, Ascher D, Cieslak T et al. Pneumococcal bacteremia during oral treatment with cefixime for otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991; 10:467-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1852543

172. Kishiyam JL. The cross-reactivity and immunology of β-lactam antibiotics. Drug Saf. 1994; 10:318-27. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8018304

173. Thompson JW. Adverse effects of newer cephalosporins: an update. Drug Saf. 1993; 9:132-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8397890

174. Zenilman JM. Typhoid fever. JAMA. 1997; 278:847-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9293994

177. Fekety R for the American College of Gastroenterology Practice Parameters Committee. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997; 92:739-50. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9149180

178. American Society of Health. ASHP therapeutic position statement on the preferential use of metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1998; 55:1407-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9659970

180. Lorenz J. Comparison of 5-day and 10-day cefixime in the treatment of acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis. Chemotherapy. 1998; 44(Suppl):15-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9797418

181. Oksi J, Nikoskelainen J. Comparison of oral cefixime and intravenous ceftriaxone followed by oral amoxicillin in disseminated lyme borreliosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998; 17:715-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9865985

182. Hoberman A, Wald ER, Hickey RW et al. Oral versus initial intravenous therapy for urinary tract infections in young febrile children. Pediatrics. 1999; 104:79-86. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10390264

183. Aracil B, Gomez-Garces JL. A study of susceptibility of 100 clinical isolates belonging to the Streptococcus milleri group to 16 cephalosporins. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999; 43:399-402. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10223596

184. Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2013; 131:e964-99. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23439909

185. Lantos PM, Rumbaugh J, Bockenstedt LK et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, American Academy of Neurology, and American College of Rheumatology: 2020 guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of Lyme disease. Neurology. 2021; 96:262-73. et al. . ;

189. Memon IA, Billoo AG, Memon HI. Cefixime: an oral option for the treatment of multidrug-resistant enteric fever in children. South Med J. 1997; 90:1204-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9404906

190. Cao XT, Kneen R, Nguyen TA et al. A comparative study of ofloxacin and cefixime for treatment of typhoid fever in children. The Dong Nai Pediatric Center Typhoid Study Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999; 18:245-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10093945

191. Girgis NI, Kilpatrick ME, Farid Z et al. Cefixime in the treatment of enteric fever in children. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1993; 19:47-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8223140

192. Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012; 54:e72-e112. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22438350

193. Wald ER, Applegate KE, Bordley C et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children Aged 1 to 18 Years. Pediatrics. 2013; :. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23796742

194. Allen VG, Mitterni L, Seah C et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae treatment failure and susceptibility to cefixime in Toronto, Canada. JAMA. 2013; 309:163-70. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23299608

195. Kirkcaldy RD, Bolan GA, Wasserheit JN. Cephalosporin-resistant gonorrhea in North America. JAMA. 2013; 309:185-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23299612

196. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Cephalosporin susceptibility among Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates--United States, 2000-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011; 60:873-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21734634

197. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update to CDC's Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010: oral cephalosporins no longer a recommended treatment for gonococcal infections. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012; 61:590-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22874837

198. Kirkcaldy RD, Zaidi A, Hook EW et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae antimicrobial resistance among men who have sex with men and men who have sex exclusively with women: the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project, 2005-2010. Ann Intern Med. 2013; 158:321-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23460055

217. Shane AL, Mody RK, Crump JA et al. 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of infectious diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2017; 65:e45-e80.

405. Herikstad H, Hayes PS, Hogan J et al. Ceftriaxone-resistant Salmonella in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997; 16:904-5

440. Panel on Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents With HIV. Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents With HIV. National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Medicine Association, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Available at https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/ guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infection. Accessed August 27, 2024. Updates may be available at HHS HIV Information website. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en

512. Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia: an official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019; 200:e45-e67.

513. Bradley JS, Byington CL, Shah SS et al. The management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011; 53:e25-76. Updates may be available at IDSA website. www.idsociety.org

744. Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. Lyme Disease (Lyme Borreliosis, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato Infection). Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024: 549-56

745. Antibacterial drugs for Lyme disease. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2021; 63:73-5.

746. Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. Gonococcal Infections. Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024:394-9.

747. Drugs for sexually transmitted infections. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2022; 64:97-104.

748. Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. Sexually Transmitted Infections. Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024:1007-16.

750. Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. Systems-based Treatment Table. Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024:1-17.

751. Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pneumococcal) Infections. Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024:810-22.

752. Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. Salmonella Infections. Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024:742-50.

753. Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. Shigella Infections. Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024:756-60.

757. Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 33rd ed. Tables of Antibacterial Drug Dosages. Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2024:987-1006.

765. Kuehn R, Stoesser N, Eyre D et al. Treatment of enteric fever (typhoid and paratyphoid fever) with cephalosporins. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022; 11:CD010452.

766. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC health advisory: XDR Salmonella Typhi infections in U.S. patients without international travel. 2021 Feb 12. Available at: https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/pdf/CDC-HAN-439-XDR-Salmonella-Typhi-Infections-in-U.S.-Without-Intl-Travel-02.12.2021.pdf. Accessed 2024 Oct 14.

Related/similar drugs

Frequently asked questions

More about cefixime

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (27)

- Drug images

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: third generation cephalosporins

- Breastfeeding

- En español