Levofloxacin (Monograph)

Brand name: Levaquin

Drug class: Quinolones

VA class: AM900

Chemical name: (S)-9-Fluoro-2,3-dihydro-3-methyl-10-(4-methyl-1-piperazinyl)-7-oxo-7H-pyrido[1,2,3-de]-1,4-benzoxazine-6-carboxylic acid hydrate (2:1)

Molecular formula: C18H20FN3O4•½H2O

CAS number: 138199-71-0

Warning

- Serious Adverse Effects

-

Fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions (e.g., tendinitis and tendon rupture, peripheral neuropathy, CNS effects) that have occurred together.1 Discontinue immediately and avoid use of fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, in patients who have experienced any of these serious adverse reactions.1 (See Warnings under Cautions.)

-

Fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, may exacerbate muscle weakness in patients with myasthenia gravis.1 Avoid in patients with known history of myasthenia gravis.1

-

Because of risk of serious adverse reactions, use levofloxacin for treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis, acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic bronchitis, or uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs) only when no other treatment options available.1

Introduction

Antibacterial; fluoroquinolone.1 2 8 12

Uses for Levofloxacin

Respiratory Tract Infections

Treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis caused by susceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, or Moraxella catarrhalis.1 2 8 18 90

Treatment of acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic bronchitis caused by susceptible Staphylococcus aureus, S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, H. parainfluenzae, or M. catarrhalis.1 2 8 19 20

Use for treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis or acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic bronchitis only when no other treatment options available.1 2 8 140 145 Because systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions (e.g., tendinitis and tendon rupture, peripheral neuropathy, CNS effects) that can occur together in the same patient (see Cautions)1 2 8 140 145 and because acute bacterial sinusitis and acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic bronchitis may be self-limiting in some patients,1 2 8 risks of serious adverse reactions outweigh benefits of fluoroquinolones for patients with these infections.140 145

Treatment of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) caused by susceptible S. aureus, S. pneumoniae (including multidrug-resistant S. pneumoniae [MDRSP]), H. influenzae, H. parainfluenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Legionella pneumoniae, M. catarrhalis, Chlamydophila pneumoniae (formerly Chlamydia pneumoniae), or Mycoplasma pneumoniae.1 2 8 21 95 512 Select regimen for empiric treatment of CAP based on most likely pathogens and local susceptibility patterns; after pathogen is identified, modify to provide more specific therapy (pathogen-directed therapy).512

Treatment of nosocomial pneumonia caused by susceptible S. aureus (oxacillin-susceptible [methicillin-susceptible] strains only), S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, Escherichia coli, K. pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, or Serratia marcescens.1 2 8 Use adjunctive therapy as clinically indicated;1 2 8 if Ps. aeruginosa known or suspected to be involved, concomitant use of an antipseudomonal β-lactam recommended.1 2 8 Select regimen for empiric treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) not associated with mechanical ventilation or ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) based on local susceptibility data.315 If a fluoroquinolone used for initial empiric treatment of HAP or VAP, IDSA and ATS recommend ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin.315

Consult current IDSA clinical practice guidelines available at [Web] for additional information on management of respiratory tract infections.315 512

Skin and Skin Structure Infections

Treatment of mild to moderate uncomplicated skin and skin structure infections (including abscesses, cellulitis, furuncles, impetigo, pyoderma, wound infections) caused by susceptible S. aureus or S. pyogenes (group A β-hemolytic streptococci.1 2 8 27 543

Treatment of complicated skin and skin structure infections caused by susceptible S. aureus (oxacillin-susceptible [methicillin-susceptible] strains only), Enterococcus faecalis, S. pyogenes, or Proteus mirabilis.1 2 8 46 58

Consult current IDSA clinical practice guidelines available at [Web] for additional information on management of skin and skin structure infections.543 544

Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) and Prostatitis

Treatment of mild to moderate uncomplicated UTIs caused by susceptible E. coli, K. pneumoniae, or S. saprophyticus.1 2 8

Use for treatment of uncomplicated UTIs only when no other treatment options available.1 2 8 140 145 Because systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions (e.g., tendinitis and tendon rupture, peripheral neuropathy, CNS effects) that can occur together in the same patient(see Cautions)1 2 8 140 145 and because uncomplicated UTIs may be self-limiting in some patients,1 2 8 risks of serious adverse reactions outweigh benefits of fluoroquinolones for patients with uncomplicated UTIs.140 145

Treatment of mild to moderate complicated UTIs caused by susceptible E. faecalis, Enterobacter cloacae, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. mirabilis, or P. aeruginosa.1 2 8

Treatment of acute pyelonephritis caused by susceptible E. coli, including cases with concurrent bacteremia.1 2 8

Treatment of chronic prostatitis caused by susceptible E. coli, E. faecalis, or S. epidermidis.1 2 8

Endocarditis

Alternative for treatment of endocarditis† [off-label] (native or prosthetic valve or other prosthetic material) caused by fastidious gram-negative bacilli known as the HACEK group (Haemophilus, Aggregatibacter, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, Kingella).450 AHA and IDSA recommend ceftriaxone (or other third or fourth generation cephalosporin),450 but state that a fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin) may be considered in patients who cannot tolerate cephalosporins.450 Consultation with an infectious disease specialist recommended.450

GI Infections

Alternative for treatment of campylobacteriosis† [off-label] caused by susceptible Campylobacter.440 Optimal treatment of campylobacteriosis in HIV-infected patients not identified.440 Some clinicians withhold anti-infective treatment in those with CD4+ T-cells >200 cells/mm3 and only mild campylobacteriosis and initiate treatment if symptoms persist for more than several days.440 In those with mild to moderate campylobacteriosis, treatment with a fluoroquinolone (preferably ciprofloxacin or, alternatively, levofloxacin or moxifloxacin) or azithromycin is reasonable.440 Modify anti-infective therapy based on results of in vitro susceptibility testing;440 resistance to fluoroquinolones reported in 22% of C. jejuni and 35% of C. coli isolates tested in US.440

Treatment of Salmonella gastroenteritis† [off-label].440 CDC, NIH, and HIV Medicine Association of IDSA recommend ciprofloxacin as initial drug of choice for treatment of Salmonella gastroenteritis (with or without bacteremia) in HIV-infected adults;440 other fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin, moxifloxacin) also likely to be effective, but data limited.440 Depending on in vitro susceptibility, alternatives are co-trimoxazole and third generation cephalosporins (ceftriaxone, cefotaxime).440 Role of long-term anti-infective treatment (secondary prophylaxis) against Salmonella in HIV-infected individuals with recurrent bacteremia not well established;440 weigh benefits of such prophylaxis against risks of long-term anti-infective therapy.440

Treatment of shigellosis† [off-label] caused by susceptible Shigella.440 Anti-infectives may not be required for mild infections, but generally indicated in addition to fluid and electrolyte replacement for treatment of patients with severe shigellosis, dysentery, or underlying immunosuppression.292 440 Empiric treatment regimen can be used initially, but in vitro susceptibility testing indicated since resistance is common.292 Fluoroquinolones (preferably ciprofloxacin or, alternatively, levofloxacin or moxifloxacin) have been recommended for treatment of shigellosis in HIV-infected adults, but consider that fluoroquinolone-resistant Shigella reported in the US, especially in international travelers, the homeless, and men who have sex with men (MSM).440 Depending on in vitro susceptibility, other drugs recommended for treatment of shigellosis include co-trimoxazole, ceftriaxone, azithromycin (not recommended in those with bacteremia), or ampicillin.197 292 440

Treatment of travelers’ diarrhea† [off-label].305 525 If caused by bacteria, may be self-limited and often resolves within 3–7 days without anti-infective treatment.305 525 CDC states anti-infective treatment not recommended for mild travelers' diarrhea;525 CDC and others state empiric short-term anti-infective treatment (single dose or up to 3 days) may be used if diarrhea is moderate or severe, associated with fever or bloody stools, or extremely disruptive to travel plans.305 525 Fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin) generally have been considered drugs of choice for empiric treatment, including self-treatment;305 525 alternatives include azithromycin and rifaximin.305 525 Consider that increasing incidence of enteric bacteria resistant to fluoroquinolones and other anti-infectives may limit usefulness of empiric treatment in individuals traveling in certain geographic areas;525 also consider possible adverse effects of the anti-infective and adverse consequences of such treatment (e.g., development of resistance, effect on normal gut microflora).525

Prevention of travelers’ diarrhea† in individuals traveling for relatively short periods to areas of risk.305 525 CDC and others do not recommend anti-infective prophylaxis in most travelers.525 May consider prophylaxis in short-term travelers who are high-risk individuals (e.g., HIV-infected or other immunocompromised individuals, travelers with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus or chronic renal failure) and those taking critical trips during which even a short episode of diarrhea could adversely affect purpose of trip.305 525 If anti-infective prophylaxis used, fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin) usually have been recommended;305 525 alternatives include azithromycin and rifaximin.305 525 Weigh use of anti-infective prophylaxis against use of prompt, early self-treatment with an empiric anti-infective if moderate to severe travelers' diarrhea occurs.525 Also consider increasing incidence of fluoroquinolone resistance in pathogens that cause travelers’ diarrhea (e.g., Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella).305 525

Has been used as a component of various multiple-drug regimens for treatment of infections caused by Helicobacter pylori†.235 236 237 Data are limited regarding prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistant H. pylori in the US; possible impact of such resistance on efficacy of fluoroquinolone-containing regimens used for treatment of H. pylori infections not known.235

Anthrax

Inhalational anthrax (postexposure) to reduce incidence or progression of disease following suspected or confirmed exposure to aerosolized Bacillus anthracis spores.1 2 8 CDC, AAP, US Working Group on Civilian Biodefense, and US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) recommend oral ciprofloxacin and oral doxycycline as initial drugs of choice for prophylaxis following such exposures, including exposures that occur in the context of biologic warfare or bioterrorism.668 671 672 673 683 686 Other oral fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, ofloxacin) are alternatives for postexposure prophylaxis when ciprofloxacin or doxycycline cannot be used.668 671 672 673

Treatment of uncomplicated cutaneous anthrax† (without systemic involvement) that occurs in the context of biologic warfare or bioterrorism.671 672 673 CDC states that preferred drugs for such infections include oral ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, levofloxacin, or moxifloxacin.672 673

Alternative to ciprofloxacin for use in multiple-drug parenteral regimens for initial treatment of systemic anthrax† (inhalational, GI, meningitis, or cutaneous with systemic involvement, head or neck lesions, or extensive edema) that occurs in the context of biologic warfare or bioterrorism.668 671 672 673 For initial treatment of systemic anthrax with possible or confirmed meningitis, CDC and AAP recommend a regimen of IV ciprofloxacin in conjunction with another IV bactericidal anti-infective (preferably meropenem) and an IV protein synthesis inhibitor (preferably linezolid).671 672 673 If meningitis excluded, these experts recommend an initial regimen of IV ciprofloxacin in conjunction with an IV protein synthesis inhibitor (preferably clindamycin or linezolid).671 672 673

Has been suggested as possible alternative to ciprofloxacin for treatment of inhalational anthrax† when a parenteral regimen not available (e.g., supply or logistic problems because large numbers of individuals require treatment in a mass-casualty setting).668

Chlamydial Infections

Alternative for treatment of urogenital infections caused by Chlamydia trachomatis†.344 CDC recommends azithromycin or doxycycline;344 alternatives are erythromycin, levofloxacin, or ofloxacin.344

Gonorrhea and Associated Infections

Was used in the past for treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea† caused by susceptible Neisseria gonorrhoeae.114

Because quinolone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae (QRNG) widely disseminated worldwide, including in the US,344 857 CDC states fluoroquinolones no longer recommended for treatment of gonorrhea and should not be used routinely for any associated infections that may involve N. gonorrhoeae (e.g., pelvic inflammatory disease [PID], epididymitis).344

Alternative for treatment of PID†.344 (See Pelvic Inflammatory Disease under Uses.)

Alternative for treatment of acute epididymitis†.344 CDC recommends a single IM dose of ceftriaxone in conjunction with oral doxycycline for acute epididymitis most likely caused by sexually transmitted chlamydia and gonorrhea or a single IM dose of ceftriaxone in conjunction with oral levofloxacin or ofloxacin for treatment of acute epididymitis most likely caused by sexually transmitted chlamydia and gonorrhea and enteric bacteria (e.g., in men who practice insertive anal sex).344 Levofloxacin or ofloxacin can be used alone if acute epididymitis most likely caused by enteric bacteria (e.g., in men who have undergone prostate biopsy, vasectomy, or other urinary tract instrumentation procedure) and gonorrhea ruled out (e.g., by gram, methylene blue, or gentian violet stain).344

Tuberculosis

Alternative (second-line) agent for use in multiple-drug regimens for treatment of active tuberculosis† caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis.218 231 276 440

Although potential role of fluoroquinolones and optimal length of therapy not fully defined, ATS, CDC, IDSA, and others state that use of fluoroquinolones as alternative (second-line) agents can be considered for treatment of active tuberculosis in patients intolerant to certain first-line agents and in those with relapse, treatment failure, or M. tuberculosis resistant to certain first-line agents.218 231 276 440 If a fluoroquinolone used in multiple-drug regimens for treatment of active tuberculosis, ATS, CDC, IDSA, and others recommend levofloxacin or moxifloxacin.218 231 276 440

Consider that fluoroquinolone-resistant M. tuberculosis reported and there are increasing reports of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR tuberculosis).70 71 72 74 75 XDR tuberculosis is caused by M. tuberculosis resistant to rifampin and isoniazid (multiple-drug resistant strains) that also are resistant to a fluoroquinolone and at least one parenteral second-line antimycobacterial (capreomycin, kanamycin, amikacin).71 72

Consult most recent ATS, CDC, and IDSA recommendations for treatment of tuberculosis for more specific information.218 440

Other Mycobacterial Infections

Has been used in multiple-drug regimens for treatment of disseminated infections caused by M. avium complex† (MAC).440

ATS and IDSA state that role of fluoroquinolones in treatment of MAC infections not established.675 If a fluoroquinolone is included in multiple-drug treatment regimen (e.g., for macrolide-resistant MAC infections), moxifloxacin or levofloxacin may be preferred,440 675 although many strains are resistant in vitro.675

Consult most recent ATS, CDC, and IDSA recommendations for treatment of other mycobacterial infections for more specific information.440 675

Nongonococcal Urethritis

Alternative for treatment of nongonococcal urethritis† (NGU).344 CDC recommends azithromycin or doxycycline;344 alternatives are erythromycin, levofloxacin, or ofloxacin.344

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Alternative for treatment of acute PID†.344 Do not use in any infections that may involve N. gonorrhoeae.114 116 344

When combined IM and oral regimen used for treatment of mild to moderately severe acute PID, CDC recommends a single IM dose of ceftriaxone, cefoxitin (with oral probenecid), or cefotaxime given in conjunction with oral doxycycline (with or without oral metronidazole).344 If a parenteral cephalosporin not feasible (e.g., because of cephalosporin allergy), CDC states regimen of oral levofloxacin, ofloxacin, or moxifloxacin given in conjunction with oral metronidazole can be considered if community prevalence and individual risk of gonorrhea is low and diagnostic testing for gonorrhea performed.344 If QRNG are identified or if in vitro susceptibility cannot be determined (e.g., only nucleic acid amplification test [NAAT] for gonorrhea available), consultation with infectious disease specialist recommended.344

Plague

Treatment of plague, including pneumonic and septicemic plague, caused by Yersinia pestis.1 2 8 683 688 Streptomycin (or gentamicin) historically has been considered regimen of choice for treatment of plague;197 292 683 688 alternatives are doxycycline (or tetracycline), chloramphenicol (a drug of choice for plague meningitis), fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin [a drug of choice for plague meningitis], levofloxacin, moxifloxacin), or co-trimoxazole (may be less effective than other alternatives).197 292 683 688 Regimens recommended for treatment of naturally occurring or endemic bubonic, septicemic, or pneumonic plague also recommended for plague that occurs following exposure to Y. pestis in the context of biologic warfare or bioterrorism.683 688

Postexposure prophylaxis following high-risk exposure to Y. pestis (e.g., household, hospital, or other close contact with an individual who has pneumonic plague; laboratory exposure to viable Y. pestis; confirmed exposure in the context of biologic warfare or bioterrorism).1 2 8 683 688 Drugs of choice for such prophylaxis are doxycycline (or tetracycline) or a fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, ofloxacin).683 688

Levofloxacin Dosage and Administration

Administration

Administer orally1 8 or by slow IV infusion.2 Do not give IM, sub-Q, intrathecally, or intraperitoneally.2

IV route indicated in patients who do not tolerate or are unable to take the drug orally and in other patients when the IV route offers a clinical advantage.2 Oral and IV routes considered interchangeable because pharmacokinetics are similar.1 2 8

Patients receiving oral or IV levofloxacin should be well hydrated and instructed to drink fluids liberally to prevent highly concentrated urine and formation of crystals in urine.1 2 8

Oral Administration

Tablets: Administer without regard to meals.1 Do not use tablets in pediatric patients weighing <30 kg.1

Oral solution: Administer 1 hour before or 2 hours after meals.8 (See Food under Pharmacokinetics.)

Tablets or oral solution: Administer orally at least 2 hours before or 2 hours after antacids containing magnesium or aluminum, metal cations (e.g., iron), sucralfate, multivitamins or dietary supplements containing iron or zinc, or buffered didanosine (pediatric oral solution admixed with antacid).1 5 8 (See Interactions.)

IV Infusion

Premixed injection for IV infusion containing 5 mg/mL in 5% dextrose (single-use flexible container): Use without further dilution.2

Concentrate for injection containing 25 mg/mL (single-use vials): Must be diluted prior to IV infusion.2

Do not admix with other drugs or infuse simultaneously through same tubing with other drugs.2 Do not infuse through same tubing with any solution containing multivalent cations (e.g., magnesium).2 If same administration set is used for sequential infusion of several different drugs, flush tubing before and after administration using an IV solution compatible with levofloxacin and the other drug(s).2

Premixed injection for IV infusion and concentrate for injection for IV infusion contain no preservatives;2 discard any unused portions.2

For solution and drug compatibility information, see Compatibility under Stability.

Dilution

Concentrate for injection containing 25 mg/mL (single-use vials): Dilute with a compatible IV solution prior to IV infusion to provide a solution containing 5 mg/mL.2

Rate of Administration

Administer doses of 250 or 500 mg by IV infusion over 60 minutes;2 administer doses of 750 mg by IV infusion over 90 minutes.2

Rapid IV infusion or injection associated with hypotension and must be avoided.2

Dosage

Dosage of oral and IV levofloxacin is identical.1 2 8

Dosage adjustments not needed when switching from IV to oral administration.1 2 8

Because safety of levofloxacin given for >28 days in adults and >14 days in pediatric patients not studied, manufacturers state use prolonged therapy only when potential benefits outweigh risks.1 2 8

Pediatric Patients

Anthrax

Postexposure Prophylaxis Following Exposure in the Context of Biologic Warfare or Bioterrorism

Oral or IVPediatric patients as young as 1 month of age†: AAP suggests 8 mg/kg (up to 250 mg) every 12 hours in those weighing <50 kg or 500 mg once daily in those weighing >50 kg.671

Children ≥6 months of age weighing <50 kg: Manufacturer recommends 8 mg/kg (up to 250 mg) every 12 hours.1 2 8

Children ≥6 months of age weighing >50 kg: Manufacturer recommends 500 mg once daily.1 2 8

Initiate prophylaxis as soon as possible following suspected or confirmed exposure to aerosolized B. anthracis.1 2 8 668 683

Because of possible persistence of B. anthracis spores in lung tissue following an aerosol exposure, CDC, AAP, and others recommend that anti-infective postexposure prophylaxis be continued for 60 days following a confirmed exposure.668 671 672 673 683

Treatment of Uncomplicated Cutaneous Anthrax (Biologic Warfare or Bioterrorism Exposure)†

OralPediatric patients ≥1 month of age†: AAP recommends 8 mg/kg (up to 250 mg) every 12 hours in those weighing <50 kg and 500 mg once daily in those weighing >50 kg.671

Recommended duration is 60 days after illness onset if cutaneous anthrax occurred after exposure to aerosolized B. anthracis spores in the context of biologic warfare or bioterrorism.671

Treatment of Systemic Anthrax (Biologic Warfare or Bioterrorism Exposure)†

IVPediatric patients ≥1 month of age† with systemic anthrax: 8 mg/kg (up to 250 mg) every 12 hours in those weighing <50 kg or 500 mg once daily in those weighing >50 kg.671

Pediatric patients ≥1 month of age† with systemic anthrax if meningitis excluded: 10 mg/kg (up to 250 mg) every 12 hours in those weighing <50 kg or 500 mg once daily in those weighing >50 kg.671

Used in multiple-drug parenteral regimen for initial treatment of systemic anthrax (inhalational, GI, meningitis, or cutaneous anthrax with systemic involvement, lesions on the head or neck, or extensive edema).671 Continue parenteral regimen for ≥2–3 weeks until patient is clinically stable and can be switched to appropriate oral anti-infective.671

If systemic anthrax occurred after exposure to aerosolized B. anthracis spores in the context of biologic warfare or bioterrorism, continue oral follow-up regimen until 60 days after illness onset.671

OralPediatric patients ≥1 month of age† (follow-up after initial multiple-drug parenteral regimen): 8 mg/kg (up to 250 mg) every 12 hours in those weighing <50 kg or 500 mg once daily in those weighing ≥50 kg.671

If systemic anthrax occurred after exposure to aerosolized B. anthracis spores in the context of biologic warfare or bioterrorism, continue oral follow-up regimen until 60 days after illness onset.672 673

Plague

Treatment or Prophylaxis of Plague

Oral or IVChildren ≥6 months of age weighing <50 kg: 8 mg/kg (up to 250 mg) every 12 hours for 10–14 days.1 2 8

Children ≥6 months of age weighing >50 kg: 500 mg once daily for 10–14 days.1 2 8 Higher dosage (i.e., 750 mg once daily) may be used if clinically indicated.1 2 8

Initiate as soon as possible after suspected or known exposure to Y. pestis.1 2 8

Adults

Respiratory Tract Infections

Acute Bacterial Sinusitis

Oral or IV500 mg once every 24 hours for 10–14 days.1 2 8 (See Respiratory Tract Infections under Uses.)

Alternatively, 750 mg once every 24 hours for 5 days.1 2 8

Acute Bacterial Exacerbations of Chronic Bronchitis

Oral or IV500 mg once every 24 hours for 7 days.1 2 8 (See Respiratory Tract Infections under Uses.)

Community-acquired Pneumonia (CAP)

Oral or IVS. aureus, S. pneumoniae (including MDRSP), K. pneumoniae, L. pneumophila, M. catarrhalis: 500 mg once every 24 hours for 7–14 days.1 2 8

S. pneumoniae (except MDRSP), H. influenzae, H. parainfluenzae, M. pneumoniae, or C. pneumoniae: 500 mg once every 24 hours for 7–14 days or, alternatively, 750 mg once every 24 hours for 5 days.1 2 8

If used for empiric treatment of CAP or treatment of CAP caused by Ps. aeruginosa, IDSA and ATS recommend 750 mg once daily.512

IDSA and ATS state that CAP should be treated for a minimum of 5 days and patients should be afebrile for 48–72 hours before discontinuing anti-infective therapy.512

Nosocomial Pneumonia

Oral or IV750 mg once every 24 hours for 7–14 days.1 2 8

Skin and Skin Structure Infections

Uncomplicated Infections

Oral or IV500 mg once every 24 hours for 7–10 days.1 2 8

Complicated Infections

Oral or IV750 mg once every 24 hours for 7–14 days.1 2 8

Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) and Prostatitis

Uncomplicated UTIs

Oral or IV250 mg once every 24 hours for 3 days.1 2 8 (See Urinary Tract Infections [UTIs] and Prostatitis under Uses.)

Complicated UTIs

Oral or IVE. faecalis, E. cloacae, or Ps. aeruginosa: 250 mg once every 24 hours for 10 days.1 2 8

E. coli, K. pneumoniae, or P. mirabilis: 250 mg once every 24 hours for 10 days or, alternatively, 750 mg once every 24 hours for 5 days.1 2 8

Acute Pyelonephritis

Oral or IVE. coli: 250 mg once every 24 hours or 10 days or, alternatively, 750 mg once every 24 hours for 5 days.1 2 8

Chronic Prostatitis

Oral or IV500 mg once every 24 hours for 28 days.1 2 8

GI Infections†

Campylobacter Infections†

Oral or IVHIV-infected: 750 mg once daily.440

Recommended treatment duration is 7–10 days for gastroenteritis or ≥14 days for bacteremic infections.440 Duration of 2–6 weeks recommended for recurrent infections.440

Salmonella Gastroenteritis†

Oral or IVHIV-infected: 750 mg once daily.440

Recommended treatment duration is 7–14 days if CD4+ T-cells ≥200 cells/mm3 (≥14 days if bacteremic or infection is complicated) or 2–6 weeks if CD4+ T-cells <200 cells/mm3.440

Consider secondary prophylaxis in those with recurrent bacteremia;440 also may consider in those with recurrent gastroenteritis (with or without bacteremia) or with CD4+ T-cells <200 cells/mm3 and severe diarrhea.440 Discontinue secondary prophylaxis if Salmonella infection resolves and there has been a sustained response to antiretroviral therapy with CD4+ T-cells >200 cells/mm3.440

Shigella Infections†

Oral or IVHIV-infected: 750 mg once daily.440

Recommended treatment duration is 7–10 days for gastroenteritis or ≥14 days for bacteremic infections.440 Up to 6 weeks may be required for recurrent infections, especially if CD4+ T-cells <200 cells/mm3.440

Treatment of Travelers’ Diarrhea†

Oral500 mg once daily for 1–3 days.305 679

Prevention of Travelers’ Diarrhea†

OralAnti-infective prophylaxis generally discouraged (see GI Infections under Uses);305 525 if such prophylaxis used, give during period of risk (not exceeding 2–3 weeks) beginning day of travel and continuing for 1 or 2 days after leaving area of risk.305

Helicobacter pylori Infection

Oral500 mg once daily usually used;235 236 237 250 mg once daily also has been used.235

Used as a component of multiple-drug regimen (see GI Infections under Uses).235 236 237

Anthrax

Postexposure Prophylaxis of Anthrax (Biologic Warfare or Bioterrorism Exposure)

Oral or IV500 mg once daily recommended by manufacturers.1 2 8

750 mg once daily recommended by CDC.672 673

Initiate prophylaxis as soon as possible following suspected or confirmed exposure to aerosolized B. anthracis.1 2 8 668 673 683

Because of possible persistence of B. anthracis spores in lung tissue following an aerosol exposure, CDC and others recommend that anti-infective postexposure prophylaxis be continued for 60 days following a confirmed exposure.668 672 673 683

Treatment of Uncomplicated Cutaneous Anthrax (Biologic Warfare or Bioterrorism Exposure)†

OralRecommended duration is 60 days if cutaneous anthrax occurred after exposure to aerosolized B. anthracis spores in the context of biologic warfare or bioterrorism.668 672 673 683 686

Treatment of Systemic Anthrax (Biologic Warfare or Bioterrorism Exposure)†

IVUsed in multiple-drug parenteral regimen for initial treatment of systemic anthrax (inhalational, GI, meningitis, or cutaneous with systemic involvement, lesions on the head or neck, or extensive edema).672 673 Continue parenteral regimen for ≥2–3 weeks until patient is clinically stable and can be switched to appropriate oral anti-infective.672 673

If anthrax occurred after exposure to aerosolized B. anthracis spores in the context of biologic warfare or bioterrorism, continue oral follow-up regimen until 60 days after illness onset.672 673

Chlamydial Infections†

Urogenital Infections†

Oral500 mg once daily for 7 days recommended by CDC for infections caused by C. trachomatis.344

Gonorrhea and Associated Infections†

Epididymitis†

Oral500 mg once daily for 10 days recommended by CDC.344

Use only when epididymitis† most likely caused by sexually transmitted enteric bacteria (e.g., E. coli) and N. gonorrhoeae ruled out.344 (See Gonorrhea and Associated Infections under Uses.)

Mycobacterial Infections†

Active Tuberculosis†

Oral or IV0.5–1 g once daily.218 Must be used in conjunction with other antituberculosis agents.218

ATS, CDC, and IDSA state data insufficient to date to support intermittent levofloxacin regimens for treatment of tuberculosis.218

Disseminated MAC Infections

OralHIV-infected: 500 mg once daily.440

Nongonococcal Urethritis†

Oral

500 mg once daily for 7 days recommended by CDC.344

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease†

Oral

500 mg once daily for 14 days given in conjunction with oral metronidazole (500 mg twice daily for 14 days).344

Use only when cephalosporins not feasible, community prevalence and individual risk of gonorrhea low, and in vitro susceptibility confirmed.344 (See Pelvic Inflammatory Disease under Uses.)

IV

500 mg once daily;344 used with or without IV metronidazole (500 mg every 8 hours).344

Use only when cephalosporins not feasible, community prevalence and individual risk of gonorrhea are low, and in vitro susceptibility confirmed.344 (See Pelvic Inflammatory Disease under Uses.)

Plague

Treatment or Prophylaxis of Plague

Oral or IV500 mg once daily for 10–14 days.1 2 8 Higher dosage (i.e., 750 mg once daily) may be used if clinically indicated.1 2 8

Initiate as soon as possible after suspected or known exposure to Y. pestis.1 2 8

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

Dosage adjustments not required.1 2 8

Renal Impairment

Adjust dosage in adults with Clcr <50 mL/minute.1 2 8 (See Table 1.) Adjustments not needed when used for treatment of uncomplicated UTIs in patients with renal impairment.1 2 8

Dosage recommendations not provided by manufacturer for pediatric patients with renal impairment.1 2 8

|

Usual Daily Dosage for Normal Renal Function (Clcr ≥ 50 mL/min) |

Clcr (mL/min) |

Dosage for Renal Impairment |

|---|---|---|

|

250 mg |

20–49 |

Dosage adjustment not required |

|

250 mg |

10–19 |

Uncomplicated UTIs: Dosage adjustment not required. Other infections: 250 mg once every 48 hours |

|

250 mg |

Hemodialysis or CAPD patients |

Information not available |

|

500 mg |

20–49 |

Initial 500-mg dose, then 250 mg once every 24 hours |

|

500 mg |

10–19 |

Initial 500-mg dose, then 250 mg once every 48 hours |

|

500 mg |

Hemodialysis or CAPD patients |

Initial 500-mg dose, then 250 mg once every 48 hours; supplemental doses not required after dialysis |

|

750 mg |

20–49 |

750 mg once every 48 hours |

|

750 mg |

10–19 |

Initial 750-mg dose, then 500 mg once every 48 hours |

|

750 mg |

Hemodialysis or CAPD patients |

Initial 750-mg dose, then 500 mg once every 48 hours; supplemental doses not required after dialysis |

Geriatric Patients

No dosage adjustments except those related to renal impairment.1 2 8 (See Renal Impairment under Dosage and Administration.)

Cautions for Levofloxacin

Contraindications

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Disabling and Potentially Irreversible Serious Adverse Reactions

Systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions (e.g., tendinitis and tendon rupture, peripheral neuropathy, CNS effects) that can occur together in the same patient.1 2 8 140 145 May occur within hours to weeks after a systemic fluoroquinolone is initiated;1 have occurred in all age groups and in patients without preexisting risk factors for such adverse reactions.1 2 8

Immediately discontinue levofloxacin at first signs or symptoms of any serious adverse reactions.1 2 8 140 145

Avoid systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, in patients who have experienced any of the serious adverse reactions associated with fluoroquinolones.1 2 8 140 145

Tendinitis and Tendon Rupture

Systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, are associated with an increased risk of tendinitis and tendon rupture in all age groups.1 2 8 128 129

Risk of developing fluoroquinolone-associated tendinitis and tendon rupture is increased in older adults (usually those >60 years of age), individuals receiving concomitant corticosteroids, and kidney, heart, or lung transplant recipients.1 2 8 128 129 (See Geriatric Use under Cautions.)

Other factors that may independently increase the risk of tendon rupture include strenuous physical activity, renal failure, and previous tendon disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis.1 2 8 Tendinitis and tendon rupture have been reported in patients receiving fluoroquinolones who did not have any risk factors for such adverse reactions.1 2 8

Fluoroquinolone-associated tendinitis and tendon rupture most frequently involve the Achilles tendon;1 2 8 also reported in rotator cuff (shoulder), hand, biceps, thumb, and other tendon sites.1 2 8

Tendinitis and tendon rupture can occur within hours or days after levofloxacin is initiated or as long as several months after completion of therapy and can occur bilaterally.1 2 8

Immediately discontinue levofloxacin if pain, swelling, inflammation, or rupture of a tendon occurs.1 2 8 128 129 (See Advice to Patients.)

Avoid systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, in patients who have a history of tendon disorders or have experienced tendinitis or tendon rupture.1 2 8

Peripheral Neuropathy

Systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, are associated with an increased risk of peripheral neuropathy.1 2 8

Sensory or sensorimotor axonal polyneuropathy affecting small and/or large axons resulting in paresthesias, hypoesthesias, dysesthesias, and weakness reported with systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin.1 2 8 130 Symptoms may occur soon after initiation of the drug and, in some patients, may be irreversible.1 130

Immediately discontinue levofloxacin if symptoms of peripheral neuropathy (e.g., pain, burning, tingling, numbness, and/or weakness) occur or if there are other alterations in sensations (e.g., light touch, pain, temperature, position sense, vibratory sensation).1 2 8 130 (See Advice to Patients.)

Avoid systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, in patients who have experienced peripheral neuropathy.1 2 8

CNS Effects

Systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, are associated with increased risk of psychiatric adverse effects, including toxic psychosis,1 2 8 hallucinations,1 2 8 paranoia,1 2 8 depression,1 2 8 suicidal thoughts or acts,1 2 8 anxiety,1 2 8 agitation,1 2 8 171 restlessness,1 2 8 nervousness,1 2 8 171 confusion,1 2 8 delirium,1 2 8 171 disorientation,1 2 8 171 disturbances in attention,1 2 8 171 insomnia,1 2 8 nightmares,1 2 8 and memory impairment.1 2 8 171 Attempted or completed suicides reported, especially in patients with a history of depression or underlying risk factor for depression.1 2 8 These adverse effects may occur after first dose.1 2 8

Systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, are associated with increased risk of seizures (convulsions), increased intracranial pressure (including pseudotumor cerebri), dizziness, and tremors.1 2 8 Use with caution in patients with known or suspected CNS disorders that predispose to seizures or lower the seizure threshold (e.g., severe cerebral arteriosclerosis, epilepsy) or with other risk factors that predispose to seizures or lower the seizure threshold (e.g., certain drugs, renal impairment).1 2 8

If psychiatric or other CNS effects occur, immediately discontinue levofloxacin and institute appropriate measures.1 2 8 (See Advice to Patients.)

Exacerbation of Myasthenia Gravis

Fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, have neuromuscular blocking activity and may exacerbate muscle weakness in myasthenia gravis patients;1 death or need for ventilatory support reported.1 2 8

Avoid use in patients with known history of myasthenia gravis.1 2 8 (See Advice to Patients.)

Sensitivity Reactions

Hypersensitivity Reactions

Serious and occasionally fatal hypersensitivity and/or anaphylactic reactions reported in patients receiving fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin.1 These reactions often occur with first dose.1 2 8

Some hypersensitivity reactions have been accompanied by cardiovascular collapse, hypotension or shock, seizures, loss of consciousness, tingling, angioedema (e.g., edema or swelling of the tongue, larynx, throat, or face), airway obstruction (e.g., bronchospasm, shortness of breath, acute respiratory distress), dyspnea, urticaria, pruritus, and other severe skin reactions.1 2 8

Other serious and sometimes fatal adverse reactions reported with fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, that may or may not be related to hypersensitivity reactions include one or more of the following: fever, rash or other severe dermatologic reactions (e.g., toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome); vasculitis, arthralgia, myalgia, serum sickness; allergic pneumonitis; interstitial nephritis, acute renal insufficiency or failure; hepatitis, jaundice, acute hepatic necrosis or failure; anemia (including hemolytic and aplastic), thrombocytopenia (including thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura), leukopenia, agranulocytosis, pancytopenia, and/or other hematologic effects.1 2 8

Immediately discontinue levofloxacin at first appearance of rash, jaundice, or any other sign of hypersensitivity.1 2 8 Institute appropriate therapy as indicated (e.g., epinephrine, corticosteroids, maintenance of an adequate airway and oxygen).1 2 8

Photosensitivity Reactions

Moderate to severe photosensitivity/phototoxicity reactions reported with fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin1 2 8

Phototoxicity may manifest as exaggerated sunburn reactions (e.g., burning, erythema, exudation, vesicles, blistering, edema) on areas exposed to sun or artificial ultraviolet (UV) light (usually the face, neck, extensor surfaces of forearms, dorsa of hands).1 2 8

Avoid unnecessary or excessive exposure to sunlight or artificial UV light (tanning beds, UVA/UVB treatment) while receiving levofloxacin.1 2 8 If patient needs to be outdoors, they should wear loose-fitting clothing that protects skin from sun exposure and use other sun protection measures (sunscreen).1 2 8

Discontinue levofloxacin if photosensitivity or phototoxicity (sunburn-like reaction, skin eruption) occurs.1 2 8

Other Warnings/Precautions

Hepatotoxicity

Severe hepatotoxicity, including acute hepatitis, has occurred in patients receiving levofloxacin and sometimes resulted in death.1 2 8 Most cases occurred within 6–14 days of initiation of levofloxacin therapy and were not associated with hypersensitivity reactions.1 2 8 The majority of fatalities were in geriatric patients ≥65 years of age.1 2 8 (See Geriatric Use under Cautions.)

Immediately discontinue levofloxacin in any patient who develops symptoms of hepatitis (e.g., loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, fever, weakness, tiredness, right upper quadrant tenderness, itching, yellowing of the skin or eyes, light colored bowel movements, or dark colored urine).1 2 8

Prolongation of QT Interval

Prolonged QT interval leading to ventricular arrhythmias, including torsades de pointes, reported with some fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin.1 2 8 37

Avoid use in patients with a history of prolonged QT interval or uncorrected electrolyte disorders (e.g., hypokalemia).1 2 8 Also avoid use in those receiving class IA (e.g., quinidine, procainamide) or class III (e.g., amiodarone, sotalol) antiarrhythmic agents.1 2 8

Risk of prolonged QT interval may be increased in geriatric patients.1 2 8 (See Geriatric Use under Cautions.)

Risk of Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection

Rupture or dissection of aortic aneurysms reported in patients receiving systemic fluoroquinolones.172 Epidemiologic studies indicate an increased risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection within 2 months following use of systemic fluoroquinolones, particularly in geriatric patients.1 2 8 Cause for this increased risk not identified.1 2 8 172

Unless there are no other treatment options, do not use systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, in patients who have an aortic aneurysm or are at increased risk for an aortic aneurysm.1 2 8 172 This includes geriatric patients and patients with peripheral atherosclerotic vascular disease, hypertension, or certain genetic conditions (e.g., Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome).172

If patient reports adverse effects suggestive of aortic aneurysm or dissection, immediately discontinue the fluoroquinolone.172 (See Advice to Patients.)

Hypoglycemia or Hyperglycemia

Systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, are associated with alterations in blood glucose concentrations, including symptomatic hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia.1 2 8 171 Blood glucose disturbances during fluoroquinolone therapy usually have occurred in patients with diabetes mellitus receiving an oral antidiabetic agent (e.g., glyburide) or insulin.1 2 8 171

Severe cases of hypoglycemia resulting in coma or death reported with some systemic fluoroquinolones.1 2 8 171 Although most reported cases of hypoglycemic coma involved patients with risk factors for hypoglycemia (e.g., older age, diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency, concomitant use of antidiabetic agents [especially sulfonylureas]), some involved patients receiving a fluoroquinolone who were not diabetic and not receiving an oral antidiabetic agent or insulin.171

Carefully monitor blood glucose concentrations when levofloxacin used in diabetic patients.1 2 8 82

If a hypoglycemic reaction occurs, discontinue the fluoroquinolone and initiate appropriate therapy immediately.1 2 8 (See Advice to Patients.)

Musculoskeletal Effects

Increased incidence of musculoskeletal disorders (arthralgia, arthritis, tendinopathy, gait abnormality) reported in pediatric patients receiving levofloxacin.1 2 8 Use in pediatric patients only for inhalational anthrax (postexposure) or treatment or prophylaxis of plague and only in those 6 months of age or older.1 2 8 (See Pediatric Use under Cautions.)

Fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, cause arthropathy and osteochondrosis in immature animals of various species.1 2 8 118 119 120 121 122 125 126 Persistent lesions in cartilage reported in levofloxacin studies in immature dogs.1

C. difficile-associated Diarrhea and Colitis

Treatment with anti-infectives alters normal colon flora and may permit overgrowth of Clostridioides difficile (formerly known as Clostridium difficile).1 2 8 302 303 304 C. difficile infection (CDI) and C. difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis (CDAD; also known as antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis or pseudomembranous colitis) reported with nearly all anti-infectives, including levofloxacin, and may range in severity from mild diarrhea to fatal colitis.1 2 8 102 106 107 302 303 304 C. difficile produces toxins A and B which contribute to development of CDAD;1 2 8 302 hypertoxin-producing strains of C. difficile are associated with increased morbidity and mortality since they may be refractory to anti-infectives and colectomy may be required.1 2 8

Consider CDAD if diarrhea develops during or after therapy and manage accordingly.1 2 8 302 303 304 Obtain careful medical history since CDAD may occur as late as 2 months or longer after anti-infective therapy is discontinued.1 2 8 302 303 304

If CDAD is suspected or confirmed, discontinue anti-infectives not directed against C. difficile as soon as possible.302 Initiate appropriate anti-infective therapy directed against C. difficile (e.g., vancomycin, fidaxomicin, metronidazole), supportive therapy (e.g., fluid and electrolyte management, protein supplementation), and surgical evaluation as clinically indicated.1 2 8 302 303 304

Selection and Use of Anti-infectives

Use for treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis, acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic bronchitis, or uncomplicated UTIs only when no other treatment options available.1 2 8 140 145 Because levofloxacin, like other systemic fluoroquinolones, has been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions (e.g., tendinitis and tendon rupture, peripheral neuropathy, CNS effects) that can occur together in the same patient, risks of serious adverse reactions outweigh benefits for patients with these infections.140 145

To reduce development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain effectiveness of levofloxacin and other antibacterials, use only for treatment or prevention of infections proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria.1 2 8

When selecting or modifying anti-infective therapy, use results of culture and in vitro susceptibility testing.1 2 8 In the absence of such data, consider local epidemiology and susceptibility patterns when selecting anti-infectives for empiric therapy.1 2 8

Information on test methods and quality control standards for in vitro susceptibility testing of antibacterial agents and specific interpretive criteria for such testing recognized by FDA is available at [Web].1 2 8

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

No adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women;1 2 8 animal studies (rats and rabbits) did not reveal evidence of fetal harm.1 2 8

Use during pregnancy only if potential benefits justify potential risks to fetus.1 2 8

Lactation

Distributed into milk following oral or IV administration.80

Discontinue nursing or the drug.1 2 8

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy not established for any indication in infants <6 months of age.1 2 8

Labeled by FDA for inhalational anthrax (postexposure) or for treatment or prophylaxis of plague in adolescents and children ≥6 months of age.1 2 8 Safety and efficacy not established for any other indication in this age group.1 2 8

Increased incidence of musculoskeletal disorders reported in pediatric patients receiving levofloxacin.1 2 8 Causes arthropathy and osteochondrosis in juvenile animals.1 2 8 (See Musculoskeletal Effects under Cautions.)

AAP states use of a systemic fluoroquinolone may be justified in children <18 years of age in certain specific circumstances when there are no safe and effective alternatives and the drug is known to be effective.110 292

Geriatric Use

No substantial differences in safety and efficacy relative to younger adults, but increased sensitivity cannot be ruled out.1 2 8

Risk of severe tendon disorders, including tendon rupture, is increased in older adults (usually those >60 years of age).1 2 8 128 129 This risk is further increased in those receiving concomitant corticosteroids.1 2 8 128 129 (See Tendinitis and Tendon Rupture under Cautions.) Use caution in geriatric adults, especially those receiving concomitant corticosteroids.1

Serious and sometimes fatal hepatotoxicity reported with levofloxacin;1 2 8 majority of fatalities have occurred in geriatric patients ≥65 years of age.1 2 8 (See Hepatotoxicity under Cautions.)

Risk of prolonged QT interval leading to ventricular arrhythmias may be increased in geriatric patients, especially those receiving concurrent therapy with other drugs that can prolong QT interval (e.g., class IA or III antiarrhythmic agents) or with risk factors for torsades de pointes (e.g., known QT prolongation, uncorrected hypokalemia).1 2 8 (See Prolongation of QT Interval under Cautions.)

Risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection may be increased in geriatric patients.1 2 8 (See Risk of Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection under Cautions.)

Consider age-related decreases in renal function when selecting dosage.1 2 8 (See Renal Impairment under Dosage and Administration.)

Hepatic Impairment

Pharmacokinetics not studied in patients with hepatic impairment, but pharmacokinetic alterations unlikely.1 2 8

Renal Impairment

Substantially decreased clearance and increased half-life.1 2 8 Use with caution and adjust dosage.1 2 8 (See Renal Impairment under Dosage and Administration.)

Perform appropriate renal function tests prior to and during therapy.1 2 8

Common Adverse Effects

GI effects (nausea, diarrhea, constipation), headache, insomnia, dizziness.1 2 8

Drug Interactions

Drugs That Prolong QT Interval

Potential pharmacologic interaction (additive effect on QT interval prolongation).1 2 8 Avoid use in patients receiving class IA (e.g., quinidine, procainamide) or class III (e.g., amiodarone, sotalol) antiarrhythmic agents.1 2 8 (See Prolongation of QT Interval under Cautions.)

Specific Drugs and Laboratory Tests

|

Drug or Test |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Antacids (aluminum- or magnesium-containing) |

Decreased absorption of oral levofloxacin;1 8 5 7 data not available regarding IV levofloxacin2 |

Administer oral levofloxacin at least 2 hours before or 2 hours after such antacids1 8 |

|

Antiarrhythmic agents |

Potential additive effects on QT interval prolongation1 2 8 Procainamide: Increased half-life and decreased clearance of procainamide84 |

Avoid levofloxacin in patients receiving class IA (e.g., quinidine, procainamide) or class III (e.g., amiodarone, sotalol) antiarrhythmic agents1 2 8 |

|

Anticoagulants, oral (warfarin) |

Monitor PT, INR, or other suitable coagulation tests and monitor for bleeding1 2 8 |

|

|

Antidiabetic agents (e.g., insulin, glyburide) |

Alterations in blood glucose (hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia) reported1 2 8 |

Closely monitor blood glucose;1 2 8 if hypoglycemic reaction occurs, immediately discontinue levofloxacin and initiate appropriate therapy1 2 8 |

|

Cimetidine |

Not considered clinically important;1 2 8 levofloxacin dosage adjustments not warranted1 2 8 |

|

|

Corticosteroids |

Increased risk of tendinitis or tendon rupture, especially in patients >60 years of age1 2 8 |

|

|

Cyclosporine or tacrolimus |

Possible increased AUC of cyclosporine or tacrolimus92 |

Manufacturer of levofloxacin states dosage adjustments not needed for either drug when levofloxacin used with cyclosporine;1 2 8 some clinicians suggest monitoring plasma concentrations of cyclosporine or tacrolimus92 |

|

Didanosine |

Possible decreased absorption of oral levofloxacin;1 8 data not available regarding IV levofloxacin2 |

Administer oral levofloxacin at least 2 hours before or 2 hours after buffered didanosine (pediatric oral solution admixed with antacid)1 8 |

|

Digoxin |

No evidence of clinically important effect on pharmacokinetics of digoxin or levofloxacin1 2 8 83 |

|

|

Iron preparations |

Decreased absorption of oral levofloxacin;1 8 data not available regarding IV levofloxacin2 |

Administer oral levofloxacin at least 2 hours before or after ferrous sulfate and dietary supplements containing iron1 8 |

|

Multivitamins and mineral supplements |

Decreased absorption of oral levofloxacin;1 94 8 data not available regarding IV levofloxacin2 |

Administer oral levofloxacin at least 2 hours before or 2 hours after supplements containing zinc, calcium, magnesium, or iron1 8 94 |

|

NSAIAs |

Possible increased risk of CNS stimulation, seizures;1 2 8 91 animal studies suggest risk may be less than that associated with some other fluoroquinolones91 |

|

|

Probenecid |

Not considered clinically important;1 2 8 levofloxacin dosage adjustments not required1 2 8 |

|

|

Psychotherapeutic agents |

Fluoxetine or imipramine: Potential additive effect on QT interval prolongation85 |

|

|

Tests for opiates |

Possibility of false-positive results for opiates in patients receiving some quinolones, including levofloxacin, when commercially available urine screening immunoassay kits are used1 2 8 |

Positive opiate urine screening test results may need to be confirmed using more specific methods1 2 8 |

|

Sucralfate |

Decreased absorption of oral levofloxacin;1 8 data not available regarding IV levofloxacin2 |

Administer oral levofloxacin at least 2 hours before or 2 hours after sucralfate1 8 86 |

|

Theophylline |

No evidence of clinically important pharmacokinetic interaction with levofloxacin;1 2 8 increased theophylline concentrations and increased risk of theophylline-related adverse effects reported with some other quinolones1 2 8 |

Closely monitor theophylline concentrations and make appropriate dosage adjustments;1 2 8 consider that adverse theophylline effects (e.g., seizures) may occur with or without elevated theophylline concentrations1 2 8 |

Levofloxacin Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Single 500- or 750-mg dose as tablets: Absolute bioavailability approximately 99%.1 8

Rapidly absorbed from GI tract.1 8 Peak plasma concentrations usually attained 1–2 hours after an oral dose;1 8 steady-state plasma concentrations attained within 48 hours with once-daily regimens.1 8

Tablets and oral solution are bioequivalent.8

Plasma concentrations and AUC after oral administration of tablets are similar to those after IV administration.1 2 8

Food

Tablets: Food slightly prolongs time to peak plasma concentration and slightly decreases peak concentrations (approximately 14%);1 86 not considered clinically important.1

Oral solution: Food decreases peak concentrations by approximately 25%.1 8

Distribution

Extent

Widely distributed into body tissues and fluids, including skin, blister fluid, and lungs.1 2 8

Distributed into CSF.5 64 65 Following IV administration of 400 or 500 mg twice daily, CSF concentrations have been reported to be up to 47% of concurrent plasma concentrations.64 65

Distributed into milk following oral or IV administration.80

Plasma Protein Binding

24–38% bound to serum proteins, principally albumin.1 2 8

Elimination

Metabolism

Undergoes limited metabolism to inactive metabolites.1 2 8

Elimination Route

Eliminated principally as unchanged drug in urine by glomerular filtration and active tubular secretion.1 2 8 Approximately 87% of an oral dose eliminated in urine and <4% eliminated in feces.1 2 8

Not removed by hemodialysis or continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD).1 2 8

Half-life

Terminal elimination half-life approximately 6–8 hours after oral or IV administration.1 2 8

Special Populations

Pediatric patients ≥6 months of age: Increased clearance and decreased plasma concentrations relative to those in adults.1 2 8

Geriatric individuals with normal renal function: Pharmacokinetics similar to that in younger adults.1 2 8

Patients with hepatic impairment: Pharmacokinetics not studied, but alterations unlikely.1 2 8

Patients with impaired renal function: Decreased clearance and prolonged half-life1 2 8 (27 hours in those with Clcr 20–49 mL/minute and 35 hours in those with Clcr <20 mL/minute).1 8

Stability

Storage

Oral

Solution

25°C (may be exposed to 15–30°C).8

Tablets

15–30°C in well-closed containers.1

Parenteral

For Injection, for IV Infusion

Single-dose vials: 15–30°C; protect from light.2 After dilution to a concentration of 5 mg/mL with compatible IV solution, stable for up to 72 hours at ≤25°C or up to 14 days at 5°C in flexible IV containers.2

Diluted solutions containing 5 mg/mL may be frozen in glass or plastic IV containers for ≤6 months at -20°C;2 after thawing at room temperature or in a refrigerator, do not refreeze.2

Contains no preservatives; discard any unused portions.2

Injection, for IV Infusion

Single-dose flexible containers: 20–25°C; do not freeze.2 Protect from light and excessive heat.2

Contains no preservatives;2 discard any unused portions.2

Compatibility

Parenteral

Solution Compatibility2 HID

|

Compatible |

|---|

|

Dextrose 5% in Ringer’s injection, lactated |

|

Dextrose 5% in sodium chloride 0.9% |

|

Dextrose 5% in water |

|

Plasma-Lyte 56 and dextrose 5% |

|

Sodium chloride 0.9% |

|

Sodium lactate 1/6 M |

|

Variable |

|

Mannitol 20% |

|

Sodium bicarbonate 5% |

Drug Compatibility

|

Compatible |

|---|

|

Linezolid |

|

Incompatible |

|

Micafungin sodium |

|

Compatible |

|---|

|

Amikacin sulfate |

|

Aminophylline |

|

Ampicillin sodium |

|

Anidulafungin |

|

Bivalirudin |

|

Caffeine citrate |

|

Cangrelor tetrasodium |

|

Caspofungin acetate |

|

Cefotaxime sodium |

|

Ceftaroline fosamil |

|

Ceftolozane sulfate-tazobactam sodium |

|

Clindamycin phosphate |

|

Cloxacillin sodium |

|

Daptomycin |

|

Dexamethasone sodium phosphate |

|

Dexmedetomidine HCl |

|

Dobutamine HCl |

|

Dopamine HCl |

|

Doripenem |

|

Epinephrine HCl |

|

Fenoldopam mesylate |

|

Fentanyl citrate |

|

Gentamicin sulfate |

|

Hetastarch in lactated electrolyte injection |

|

Hydromorphone HCL |

|

Isavuconazonium sulfate |

|

Isoproterenol HCl |

|

Lidocaine HCl |

|

Linezolid |

|

Lorazepam |

|

Magnesium sulfate |

|

Meropenem-vaborbactam |

|

Metoclopramide HCl |

|

Morphine sulfate |

|

Oxacillin sodium |

|

Pancuronium bromide |

|

Penicillin G sodium |

|

Phenobarbital sodium |

|

Phenylephrine HCl |

|

Posaconazole |

|

Potassium chloride |

|

Sodium bicarbonate |

|

Tedizolid phosphate |

|

Vancomycin HCl |

|

Incompatible |

|

Acyclovir sodium |

|

Alprostadil |

|

Azithromycin |

|

Furosemide |

|

Heparin sodium |

|

Indomethacin sodium trihydrate |

|

Letermovir |

|

Nitroglycerin |

|

Plazomicin |

|

Sodium nitroprusside |

|

Telavancin HCl |

|

Variable |

|

Insulin, regular |

Actions and Spectrum

-

Like other fluoroquinolones, levofloxacin inhibits bacterial DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV.1 2 4 8 39

-

Spectrum of activity includes gram-positive aerobic bacteria, some gram-negative aerobic bacteria, some anaerobic bacteria, and some other organisms (e.g., Chlamydia, Mycoplasma, Mycobacterium).1 2 3 8 13 14 15 16 17 40 41 42

-

More active in vitro against gram-positive bacteria, (including S. pneumoniae) and anaerobes than some other fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin),3 13 14 15 16 17 but less active in vitro than ciprofloxacin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa.3 14 17

-

Gram-positive aerobes: Active in vitro and in clinical infections against S. aureus (oxacillin-susceptible [methicillin-susceptible] strains only), S. epidermidis (oxacillin-susceptible strains only), S. saprophyticus, S. pneumoniae (including penicillin-resistant strains), S. pyogenes (group A β-hemolytic streptococci, GAS), and Enterococcus faecalis (many strains only moderately susceptible).1 2 3 8 Also active in vitro against S. haemolyticus, S. agalactiae (group B streptococci, GBS), groups C, G, and F streptococci, S. milleri, and viridans streptococci.1 2 3 8 Active against Bacillus anthracis in vitro and in a primate infection model.1 2 8 93

-

Gram-negative aerobes: Active in vitro and in clinical infections against H. influenzae, H. parainfluenzae, K. pneumoniae, M. catarrhalis, E. cloacae, E. coli, P. mirabilis, S. marcescens, Ps. aeruginosa (some may develop resistance during therapy), and Legionella pneumophila.1 2 8 3 Also active in vitro against Acinetobacter, Bordetella pertussis, Citrobacter, E. aerogenes, E. sakazakii, K. oxytoca, Morganella morganii, Pantoea agglomerans, P. vulgaris, Providencia, and Ps. fluorescens.1 2 8 Active against Y. pestis in vitro and in a primate infection model.1 2 8 Has in vitro activity against H. pylori,241 but resistance occurs and prevalence of levofloxacin-resistant strains may be high in some geographic areas.235 239 240

-

Anaerobes and other organisms: Active in vitro and in clinical infections against C. pneumoniae 1 2 8 and M. pneumoniae.1 2 3 8 Also active in vitro against Clostridium perfringens,1 2 3 8 Mycobacterium tuberculosis,40 41 111 and M. fortuitum.42

-

N. gonorrhoeae with decreased susceptibility to levofloxacin and other fluoroquinolones (quinolone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae; QRNG) are widely disseminated worldwide, including in the US.53 109 114 132 344

-

Resistance to fluoroquinolones can occur as the result of mutations in defined regions of DNA gyrase or topoisomerase IV (i.e., quinolone-resistance determining regions [QRDRs]) or altered efflux.1 2 8

-

Some cross-resistance occurs between levofloxacin and other fluoroquinolones.1 2 8

Advice to Patients

-

Advise patients to read manufacturer’s patient information (medication guide) prior to initiating levofloxacin therapy and each time prescription refilled.1 2 8

-

Advise patients that antibacterials (including levofloxacin) should only be used to treat bacterial infections and not used to treat viral infections (e.g., the common cold).1 2 8

-

Importance of completing full course of therapy, even if feeling better after a few days.1 2 8

-

Advise patients that skipping doses or not completing the full course of therapy may decrease effectiveness and increase the likelihood that bacteria will develop resistance and will not be treatable with levofloxacin or other antibacterials in the future.1 2 8

-

Advise patients that the oral solution should be taken 1 hour before or 2 hours after meals;8 tablets may be taken without regard to meals1

-

Levofloxacin should be taken at the same time each day and with liberal amounts of fluids to prevent highly concentrated urine and formation of crystals in urine.1 8

-

Importance of taking oral levofloxacin at least 2 hours before or 2 hours after aluminum- or magnesium-containing antacids, metal cations (e.g., iron), sucralfate, multivitamins containing iron or zinc, or buffered didanosine (pediatric oral solution prepared as an admixture with antacid).1 8

-

Inform patients that systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions (e.g., tendinitis and tendon rupture, peripheral neuropathy, CNS effects) that may occur together in same patient.1 2 8 140 145 Advise patients to immediately discontinue levofloxacin and contact a clinician if they experience any signs or symptoms of serious adverse effects (e.g., unusual joint or tendon pain, muscle weakness, a “pins and needles” tingling or pricking sensation, numbness of the arms or legs, confusion, hallucinations) while taking the drug.1 140 145 Advise patients to talk with a clinician if they have any questions or concerns.1 140 145

-

Inform patients that systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, are associated with an increased risk of tendinitis and tendon rupture in all age groups and this risk is increased in adults >60 years of age, individuals receiving corticosteroids, and kidney, heart, or lung transplant recipients.1 2 8 Symptoms may be irreversible.1 2 8 Importance of resting and refraining from exercise at the first sign of tendinitis or tendon rupture (e.g., pain, swelling, or inflammation of a tendon or weakness or inability to use a joint) and importance of immediately discontinuing the drug and contacting a clinician.1 2 8 (See Tendinitis and Tendon Rupture under Cautions.)

-

Inform patients that peripheral neuropathies have been reported with systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, and that symptoms may occur soon after initiation of the drug and may be irreversible.1 2 8 Importance of immediately discontinuing levofloxacin and contacting a clinician if symptoms of peripheral neuropathy (e.g., pain, burning, tingling, numbness, and/or weakness) occur.1 2 8

-

Inform patients that systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, have been associated with CNS effects (e.g., convulsions, dizziness, lightheadedness, increased intracranial pressure).1 2 8 Importance of informing clinician of any history of convulsions before initiating therapy with the drug.1 2 8 Importance of contacting a clinician if persistent headache with or without blurred vision occurs.1 2 8

-

Advise patients that levofloxacin may cause dizziness and lightheadedness;1 2 8 caution patients not to engage in activities requiring mental alertness and motor coordination (e.g., driving a vehicle, operating machinery) until effects of the drug on the individual are known.1 2 8

-

Advise patients that systemic fluoroquinolones, including levofloxacin, may worsen myasthenia gravis symptoms;1 2 8 importance of informing clinician of any history of myasthenia gravis.1 2 8 Importance of immediately contacting a clinician if any symptoms of muscle weakness, including respiratory difficulties, occur.1 2 8

-

Inform patients that levofloxacin may be associated with hypersensitivity reactions (including anaphylactic reactions), even after first dose.1 2 8 Importance of immediately discontinuing levofloxacin and contacting a clinician at first sign of rash or any symptom of hypersensitivity (e.g., hives, other skin reaction, rapid heartbeat, difficulty swallowing or breathing, throat tightness, hoarseness, swelling of lips, tongue, or face).1 2 8

-

Inform patients that photosensitivity/phototoxicity reactions reported following exposure to sun or UV light in patients receiving fluoroquinolones.1 2 8 Importance of avoiding or minimizing exposure to sunlight or artificial UV light (e.g., tanning beds, UVA/UVB treatment) and using protective measures (e.g., wearing loose-fitting clothes, sunscreen) if outdoors during levofloxacin therapy.1 2 8 Importance of discontinuing levofloxacin and contacting a clinician if a sunburn-like reaction or skin eruption occurs.1 2 8

-

Inform patients that severe hepatotoxicity (including acute hepatitis and fatal events) reported in patients receiving levofloxacin.1 2 8 Importance of immediately discontinuing levofloxacin and informing a clinician if any signs or symptoms of liver injury (e.g., loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, fever, weakness, tiredness, right upper quadrant tenderness, itching, yellowing of the skin and eyes, light colored bowel movements, dark colored urine) occur.1 2 8

-

Importance of informing clinician of personal or family history of QT interval prolongation or proarrhythmic conditions (e.g., recent hypokalemia, bradycardia, recent myocardial ischemia) and of concurrent therapy with any drugs that may affect QT interval (e.g., class IA [quinidine, procainamide] or class III [e.g., amiodarone, sotalol] antiarrhythmic agents).1 2 8 Importance of contacting a clinician if symptoms of prolonged QT interval (e.g., prolonged heart palpitations, loss of consciousness) occur.1 2 8

-

Inform patients that systemic fluoroquinolones may increase risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection;172 importance of informing clinician of any history of aneurysms, blockages or hardening of the arteries, high blood pressure, or genetic conditions such as Marfan syndrome or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.172 Advise patients to seek immediate medical treatment if they experience sudden, severe, and constant pain in the stomach, chest, or back.1 2 8 172

-

Inform patients that hypoglycemia reported when systemic fluoroquinolones were used in some patients receiving antidiabetic agents.171 Advise patients with diabetes mellitus receiving insulin or oral antidiabetic agents to discontinue levofloxacin and contacting a clinician if they experience hypoglycemia or symptoms of hypoglycemia.1 2 8

-

Advise patients that diarrhea is a common problem caused by anti-infectives and usually ends when the drug is discontinued.1 2 8 Importance of contacting a clinician if watery and bloody stools (with or without stomach cramps and fever) occur during or as late as 2 months or longer after the last dose.1 2 8

-

If considering levofloxacin for a pediatric patient (see Pediatric Use under Cautions), importance of parent informing clinician if the child has a history of joint-related problems.1 2 8 Importance of parent contacting a clinician if the child develops any joint-related problems during or following levofloxacin therapy.1 2 8

-

Advise patients receiving levofloxacin for inhalational anthrax (postexposure) or for treatment or prophylaxis of plague that human efficacy studies have not been performed for ethical and feasibility reasons; use in these conditions based on animal efficacy studies.1 2 8

-

Importance of informing clinician of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs (e.g., drugs that may affect QT interval, antidiabetic agents, warfarin), as well as any concomitant illnesses.1 2 8

-

Importance of women informing clinicians if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1 2 8

-

Importance of advising patients of other important precautionary information.1 2 8 (See Cautions.)

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Solution |

125 mg/5 mL* |

levoFLOXacin Solution |

|

|

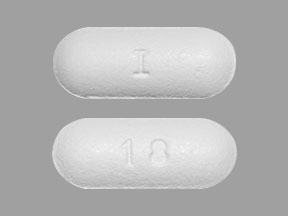

Tablets, film-coated |

250 mg (of anhydrous levofloxacin)* |

Levaquin |

Janssen |

|

|

levoFLOXacin Tablets |

||||

|

500 mg (of anhydrous levofloxacin)* |

Levaquin |

Janssen |

||

|

levoFLOXacin Tablets |

||||

|

750 mg (of anhydrous levofloxacin)* |

Levaquin |

Janssen |

||

|

levoFLOXacin Tablets |

||||

|

Parenteral |

For injection, concentrate, for IV infusion |

equivalent to levofloxacin 25 mg/mL (500 mg)* |

levoFLOXacin Concentrate, for IV Infusion |

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Parenteral |

Injection, for IV infusion |

equivalent to levofloxacin 5 mg/mL (250, 500, or 750 mg) in 5% Dextrose* |

levoFLOXacin in Dextrose Injection |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions April 10, 2024. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

1. Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc. Levaquin (levofloxacin) tablets, film coated prescribing information. Titusville, NJ; 2019 May.

2. Baxter Healthcare Corporation. Levofloxacin injection, solution prescribing information. Deerfield, IL; 2019 Mar.

3. Davis R, Bryson HM. Levofloxacin: a review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1994; 47:677-700. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7516863

4. Zhanel GC, Ennis K, Vercaigne L et al. A critical review of the fluoroquinolones: focus on respiratory tract infections. Drugs. 2002. 62:13-59.

5. Fish DN, Chow AT. The clinical pharmacokinetics of levofloxacin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997; 32:101-19. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9068926

6. Williams NA, Bornstein M, Johnson K. Stability of levofloxacin in intravenous solutions in polyvinyl chloride bags. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1996; 53:2309-13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8893070

7. Shiba K, Sakai O, Shimada J et al. Effects of antacids, ferrous sulfate, and ranitidine on absorption of DR-3355 in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992; 36:2270-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1444308 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC245488/

8. Hi-Tech Pharmacal Co., Inc. Levofloxacin oral solution prescribing information. Amityville, NY; 2019 Mar.

9. Christ W, Lehnert T, Ulbrich B. Specific toxicologic aspects of the quinolones. Rev Infect Dis. 1988; 10(Suppl 1):S141-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3279489

10. Reviewer’s comments (personal observations) on ciprofloxacin 8:12.18.

12. Une T, Fujimoto T, Sato K et al. In vitro activity of DR-3355, an optically active ofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988; 32:1336-40. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3195996 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC175863/

13. Plouffe JF and the Franklin County Pneumonia Study Group. Levofloxacin in vitro activity against bacteremic isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996; 25:43-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8831044

14. Goa KL, Bryson HM, Markham A. Sparfloxacin: a review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties, clinical efficacy and tolerability in lower respiratory tract infections. Drugs. 1997; 53:700-25. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9098667

15. Hecht DW, Wexler HM. In vitro susceptibility of anaerobes to quinolones in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 1996; 23(Suppl 1):S2-8.

16. Eliopoulos GM. In vitro activity of fluoroquinolones against gram-positive bacteria. Drugs. 1995; 49(Suppl 2):48-57. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8549407

17. Hooper DC. Quinolones. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R eds. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1995:366-7.

18. Adeglass J, DeAbate AC, McElvaine P et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of levofloxacin and amoxicillin-clavulanate for the treatment of acute sinusitis in adults. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999; 120:320-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10064632

19. DeAbate CA, Russell M, McElvaine P et al. Safety and efficacy of oral levofloxacin versus cefuroxime axetil in acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis. Respir Care. 1997; 42:206-13.