Etanercept (Monograph)

Brand name: Enbrel

Drug class: Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors, Miscellaneous

Warning

- Serious Infections

-

Increased risk of serious infections involving various organ systems and sites that may require hospitalization or result in death; tuberculosis (frequently disseminated or extrapulmonary), invasive fungal infections (may be disseminated), bacterial (e.g., legionellosis, listeriosis) and viral infections, and other opportunistic infections reported.1 137

-

Evaluate patients for latent tuberculosis infection prior to and periodically during etanercept therapy; if indicated, initiate appropriate antimycobacterial regimen prior to initiating etanercept therapy.1 137

-

Closely monitor patients for infection, including active tuberculosis in those with a negative tuberculin skin test, during and after treatment.1 137 Discontinue etanercept if serious infection or sepsis occurs.1

Introduction

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD); a recombinant soluble dimeric fusion protein.1 2 3 4 5 6 8 9 33

Uses for Etanercept

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Used to manage the signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis, to induce a major clinical response, to improve physical function, and to inhibit progression of structural damage in adults with moderate to severe disease.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 15 17 33 35 52 70 80 81 111 112 117 120 147

Can be used alone or in combination with methotrexate.1

Disease-modifying treatments for rheumatoid arthritis include conventional DMARDs (e.g., hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, methotrexate, sulfasalazine), biologic DMARDs (e.g., TNF blocking agents, abatacept, tocilizumab, sarilumab, rituximab), and/or targeted synthetic DMARDs (e.g., Janus kinase inhibitors).2003

Guidelines generally support use of TNF blocking agents as add-on therapy to methotrexate in patients who do not meet treatment goals with methotrexate alone.2003

Specific agents for rheumatoid arthritis are selected according to current disease activity, prior therapies used, and presence of comorbidities.2003

Polyarticular Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Used to manage the signs and symptoms of moderate to severe active polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis in pediatric patients ≥2 years of age.1 29 97 146 148

Drugs used for treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis include NSAIAs, systemic and intra-articular corticosteroids, conventional DMARDs (e.g., methotrexate, sulfasalazine, hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide), and biologic DMARDs (e.g., TNF blocking agents, abatacept, tocilizumab, rituximab).2013

Guidelines generally support use of TNF blocking agents as add-on therapy in patients with moderate to high disease activity despite the use of methotrexate.2013

Specific agents for juvenile idiopathic arthritis treatment are selected according to presence of certain risk factors (e.g., positive anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, positive rheumatoid factor, joint damage), level of disease activity, involvement of specific joints, presence of certain comorbidities (e.g., uveitis), and prior therapies.2013 2022

Psoriatic Arthritis

Used alone or in combination with methotrexate to manage the signs and symptoms of active psoriatic arthritis in adults, to improve physical function and to inhibit progression of structural damage.1 72 118 149 150

Disease-modifying treatments for psoriatic arthritis include oral small molecules (OSMs; e.g., methotrexate, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine, leflunomide, apremilast), biologic DMARDs (e.g., TNF blocking agents, secukinumab, ixekizumab, ustekinumab, brodalumab, abatacept), and/or targeted synthetic DMARDs (e.g., tofacitinib).2005

Guidelines generally support use of TNF blocking agents as first-line treatment in patients with active psoriatic arthritis.2005

Recommendations for the use and selection of disease-modifying therapies in psoriatic arthritis vary based on the presence of certain disease characteristics (e.g., psoriatic spondylitis/axial disease, enthesitis) and comorbidities (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes).2005

Ankylosing Spondylitis

Used to manage the signs and symptoms of active ankylosing spondylitis in adults.1 121 151 152

Treatments for ankylosing spondylitis include NSAIAs, conventional DMARDs (e.g., methotrexate, sulfasalazine), biologic DMARDs (e.g., TNF blocking agents, secukinumab, ixekizumab), and/or targeted synthetic DMARDs (e.g., tofacitinib).2004

Guidelines generally support use of TNF blocking agents for treatment of ankylosing spondylitis in patients with active disease despite treatment with NSAIAs.2004

Recommendations for treatment selection in ankylosing spondylitis vary based the presence of certain comorbidities (e.g., iritis, inflammatory bowel disease).2004

Plaque Psoriasis

Used to manage moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis in adults who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy.1 108 109 119 153 154 155 156 157

Guidelines generally support use of TNF blocking agents in adults with moderate to severe psoriasis, either as monotherapy or in combination with topical, oral, or phototherapy.2007 2009 Recommendations for use and selection of psoriasis therapies vary based on patient age, disease characteristics (e.g., severity, location, presence of psoriatic arthritis), and comorbidities (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease).2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Used to manage moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis in pediatric patients ≥4 years of age who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy.1 158 159 160 Guidelines support the use of etanercept for moderate to severe psoriasis in pediatric patients ≥6 years of age.2010

Juvenile Psoriatic Arthritis

Used for the treatment of active juvenile psoriatic arthritis in pediatric patients ≥2 years of age.1

Nonradiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis

May be useful for the management of nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis† [off-label].161 162 163

Acute Graft Versus Host Disease

Has been used for the management of acute graft versus host disease† [off-label].164 165 166 167 168 169

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

Has been investigated for the management of granulomatosis with polyangiitis† [off-label]59 (previously designated an orphan drug by FDA for this use).57 However, use with standard immunosuppressive agents has been associated with an increased incidence of solid malignant tumors without added clinical benefit.103 110 122 Therefore, use in this condition not recommended.1 103 110 122

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Not effective in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease† [off-label].1

Etanercept Dosage and Administration

General

Pretreatment Screening

-

Evaluate all patients for active and latent tuberculosis prior to initiating therapy.1

-

Complete all age-appropriate vaccinations as recommended by current immunization guidelines prior to treatment.1

-

Screen at-risk patients for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection before initiating therapy.1

-

Do not initiate therapy in patients with an active infection, including clinically important localized infections.1

Patient Monitoring

-

Periodically test all patients for active and latent tuberculosis during therapy.1

-

Monitor closely for signs or symptoms of infection (e.g., fever, malaise, weight loss, sweats, cough, dyspnea, pulmonary infiltrates, serious systemic illness including shock) during and after treatment.1

-

Perform periodic dermatologic evaluations in all patients at increased risk for skin cancer.1

-

Evaluate and monitor chronic carriers of HBV during treatment and for up to several months following treatment.1

Dispensing and Administration Precautions

-

To avoid medication errors, the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) recommends that prescribers communicate both the brand and generic names for etanercept on the prescription order form.170

Other General Considerations

-

Methotrexate, glucocorticoids, salicylates, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIAs), and analgesics may be continued in adults receiving etanercept for the management of rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or psoriatic arthritis.1 7

-

Glucocorticoids, NSAIAs, and analgesics may be continued in pediatric patients with polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis receiving etanercept.1

Administration

Administer by sub-Q injection.1

Sub-Q Administration

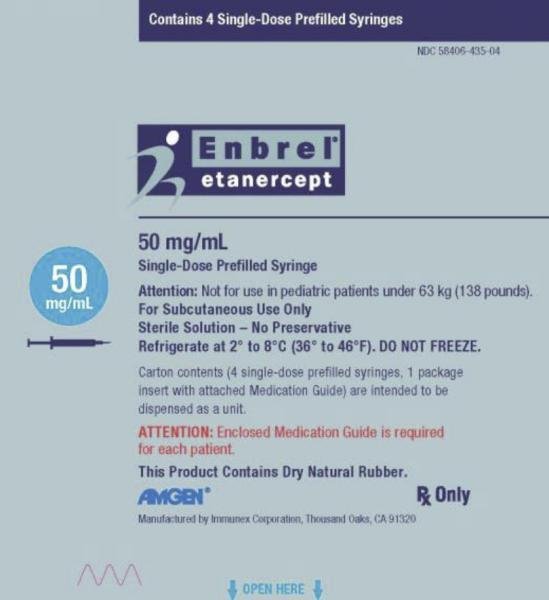

Administer a 50-mg dose as a single injection using the 50 mg/mL prefilled syringe, prefilled autoinjector, or prefilled cartridge, or as 2 injections using the 25 mg/0.5 mL prefilled syringe given on the same day once a week or on 2 different days 3–4 days apart.1 133 A 50-mg dose can also be obtained using two 25-mg single-dose vials or two 25-mg multidose vials of lyophilized etanercept, when the multidose vials are reconstituted and administered as recommended.1 133 134

Administer sub-Q injections into the thighs, abdomen, or upper arm.132 133 134 Rotate injection sites.132 133 134 Do not inject into areas where skin is tender, bruised, red, or hard, or into scars, stretch marks, or psoriatic lesions.132 133 134

For greater patient comfort, allow etanercept prefilled syringe to reach room temperature for about 15–30 minutes prior to administration; allow single-dose vial to reach room temperature for ≥30 minutes prior to administration.1 Allow single-dose prefilled cartridges and the prefilled auto-injector to reach room temperature for ≥30 minutes prior to administration.1

Do not remove the needle cover from the prefilled syringe or prefilled auto-injector until immediately before administration.1 132 133 Do not remove the purple cap from the single-use prefilled cartridge until the cartridge is inside the reusable autoinjector, immediately prior to administration; do not leave the purple cap off for >5 minutes prior to injection.1

When preparing a dose of etanercept from a single-dose vial of etanercept solution, use a 1-mL Luer-Lock syringe and a 22-gauge needle with Luer-Lock connection to withdraw the dose from the vial; use a 27-gauge needle with Luer-Lock connection to administer the dose.1 If 2 vials are required to administer the total prescribed etanercept dose, use the same syringe for each vial.1 Single-dose vials do not contain preservatives; discard any unused portion.1 Solution may contain small, white, proteinaceous particulates; do not administer if discolored or cloudy, or if foreign particulate matter is present.1

Intended for use under the guidance and supervision of a clinician, but may be self-administered if the clinician determines that the patient and/or their caregiver is competent to prepare and safely administer the drug.1 The initial self-administered dose should be made under the supervision of a healthcare professional.1

Reconstitution (25-mg Multiple-dose Vial)

For greater patient comfort, allow dose tray containing etanercept lyophilized powder and diluent to reach room temperature (about 15–30 minutes) prior to administration.1

Reconstitute lyophilized powder by adding 1 mL of bacteriostatic water for injection (containing 0.9% benzyl alcohol) provided by the manufacturer to a 25-mg vial to provide a solution containing 25 mg/mL.1

During reconstitution, very slowly add the diluent to the vial and gently swirl the contents to minimize foaming during dissolution; some foaming will occur.1

May use vial adapter supplied by manufacturer to facilitate reconstitution and withdrawal of dose if only one dose will be withdrawn from the vial.1 If multiple doses will be withdrawn from the vial, use a syringe with a 25-gauge needle for reconstitution and withdrawal of dose from vial.1 134 Use a 27-gauge needle to administer the dose.1

Avoid shaking and excessive or vigorous agitation of the vial to avoid excessive foaming.1

The final volume in the vial will be about 1 mL.134

Dissolution usually takes less than 10 minutes.1

Do not filter solutions during preparation or administration.1

Do not mix contents of one vial with, or transfer contents of one vial into, contents of another vial.1 Do not mix with other drugs.1

Preparation Considerations

To achieve pediatric doses other than 25 mg or 50 mg, use the single-dose vial or reconstituted lyophilized powder in a multiple-dose vial.1

Do not use 25-mg/0.5 mL prefilled syringe in pediatric patients weighing <31 kg.133 Do not use 50-mg/mL prefilled syringe, prefilled single-dose auto-injector, or prefilled single-dose auto-injector cartridge in pediatric patients weighing <63 kg.1 132 133

Dosage

Pediatric Patients

Polyarticular Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Sub-Q

Pediatric patients 2–17 years of age: 0.8 mg/kg (maximum 50 mg) once weekly in patients <63 kg; 50 mg once weekly in patients ≥63 kg.1

Plaque Psoriasis

Sub-Q

Pediatric patients 4–17 years of age: 0.8 mg/kg (maximum 50 mg) once weekly in patients <63 kg; 50 mg once weekly in patients ≥63 kg.1

Juvenile Psoriatic Arthritis

Sub-Q

Pediatric patients 2–17 years of age: 0.8 mg/kg (maximum 50 mg) once weekly in patients <63 kg; 50 mg once weekly in patients ≥63 kg.1

Adults

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Sub-Q

50 mg once weekly.1

Psoriatic Arthritis

Sub-Q

50 mg once weekly.1

Ankylosing Spondylitis

Sub-Q

50 mg once weekly.1

Psoriasis

Sub-Q

Initially, 50 mg twice weekly for 3 months.1 Initial dosages of 25 mg or 50 mg once weekly also have been effective; a dose-related effect observed.1

Maintenance dosage: 50 mg once weekly.1

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

No specific dosage recommendations at this time.1

Renal Impairment

No specific dosage recommendations at this time.1

Geriatric Patients

No specific dosage recommendations at this time; however, use caution since there is an increased incidence of infections among the geriatric population.1

Patients with Diabetes

May need to reduce anti-diabetic medication in some patients as hypoglycemia reported following initiation of etanercept in patients with diabetes.1

Cautions for Etanercept

Contraindications

-

Sepsis.1

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Serious Infections

Increased risk of serious infections involving various organ systems, possibly resulting in hospitalization or death (see Boxed Warning).1 137 Opportunistic infections caused by bacterial, mycobacterial, invasive fungal, viral, parasitic, or other opportunistic organisms (e.g., aspergillosis, blastomycosis, candidiasis, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, legionellosis, listeriosis, pneumocystosis, tuberculosis) reported, particularly in patients receiving concomitant therapy with immunosuppressive agents (e.g., methotrexate, corticosteroids).1 137 Infections frequently are disseminated.1

Increased incidence of serious infections observed with concomitant use of a TNF blocking agent and anakinra or abatacept.1 127 Concomitant use of etanercept and abatacept or anakinra not recommended.1

Patients >65 years of age, with comorbid conditions, and/or receiving concomitant therapy with immunosuppressive agents (e.g., corticosteroids, methotrexate) may be at increased risk of infection.1 137

Do not initiate etanercept in patients with active infections, including clinically important localized infections.1 16 36 48 Consider potential risks and benefits of the drug prior to initiating therapy in patients with a history of chronic, recurring, or opportunistic infections; patients with underlying conditions that may predispose them to infections; and patients who have been exposed to tuberculosis or who have resided or traveled in regions where tuberculosis or mycoses such as histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and blastomycosis are endemic.1 137

Closely monitor patients during and after etanercept therapy for signs or symptoms of infection (e.g., fever, malaise, weight loss, sweats, cough, dyspnea, pulmonary infiltrates, serious systemic illness including shock), including the possible development of tuberculosis in patients who tested negative for latent tuberculosis prior to initiating therapy.1 137

If new infection occurs during therapy, perform thorough diagnostic evaluation (appropriate for immunocompromised patient), initiate appropriate anti-infective therapy, and closely monitor patient.1 Discontinue etanercept if serious infection or sepsis develops.1 16 36 48

Evaluate all patients for active or latent tuberculosis and for risk factors for tuberculosis prior to and periodically during therapy.1 137 When indicated, initiate appropriate antimycobacterial regimen for treatment of latent tuberculosis infection prior to etanercept therapy.1 Also consider antimycobacterial therapy prior to etanercept therapy for individuals with a history of latent or active tuberculosis in whom an adequate course of antimycobacterial treatment cannot be confirmed and for individuals with a negative tuberculin skin test who have risk factors for tuberculosis.1 Consultation with a tuberculosis specialist is recommended when deciding whether to initiate antimycobacterial therapy.1

Reactivation of latent tuberculosis reported in patients receiving etanercept, although data suggest that risk is lower with etanercept than with TNF-blocking monoclonal antibodies.1

Monitor all patients, including those with negative tuberculin skin tests, for active tuberculosis.1 Strongly consider tuberculosis in patients who develop new infections while receiving etanercept, especially if they previously have traveled to countries where tuberculosis is highly prevalent or have been in close contact with an individual with active tuberculosis.1

Failure to recognize invasive fungal infections has led to delays in appropriate treatment. Consider empiric antifungal therapy in patients at risk for invasive fungal infections who develop severe systemic illness.1 137 Whenever feasible, consult specialist in fungal infections when making decisions regarding initiation and duration of antifungal therapy.1

When deciding whether to reinitiate TNF blocking agent therapy following resolution of an invasive fungal infection, reevaluate risks and benefits, particularly in patients who reside in regions where mycoses are endemic. Whenever feasible, consult specialist in fungal infections.

Malignancies

Cases of lymphoma and other malignancies (some fatal) reported in children, adolescents, and adults receiving TNF blocking agents; patients receiving other immunosuppressive agents (e.g., azathioprine, methotrexate) concomitantly may be at increased risk (see Boxed Warning).1 128 Malignancies included lymphomas (e.g., Hodgkin disease, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma) and various other malignancies (e.g., leukemia, melanoma, solid organ cancers, leiomyosarcoma, hepatic malignancies, renal cell carcinoma).1 128 138

FDA has concluded that there is an increased risk of malignancy with TNF blocking agents; however, the strength of the association is not fully characterized.128

Solid noncutaneous malignant tumors reported in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis receiving etanercept and cyclophosphamide.1 122

Consider possibility of and monitor for occurrence of malignancies during and following treatment with TNF blocking agents.128 138

Consider periodic dermatologic examinations in all patients at increased risk.1

Carefully consider risks and benefits of TNF blocking agents, especially in adolescents and young adults and especially in the treatment of Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis;138 etanercept is not effective in the management of inflammatory bowel disease.1

Other Warnings and Precautions

Neurologic Reactions

New onset or exacerbation of CNS demyelinating disorders (some presenting with mental status changes and some associated with permanent disability) and peripheral nervous system demyelinating disorders reported rarely with etanercept or other TNF blocking agents.1

Multiple sclerosis, transverse myelitis, optic neuritis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, peripheral demyelinating neuropathies, and new onset or exacerbation of seizure disorders reported in patients receiving etanercept.1

Exercise caution when considering etanercept therapy in patients with preexisting or recent-onset central or peripheral nervous system demyelinating disorders.1

New Onset or Worsening of Heart Failure

Worsening CHF (with and without identifiable precipitating factors) and, rarely, new-onset CHF (including in patients without known cardiovascular disease) reported, sometimes in patients <50 years of age.1 Use with caution and monitor carefully in patients with heart failure.1

One study evaluating etanercept for treatment of CHF suggested higher mortality rate in etanercept-treated patients versus placebo recipients.1

Hematologic Reactions

Possible pancytopenia including aplastic anemia, sometimes with fatal outcome.1 Use with caution in patients with a history of substantial hematologic abnormalities.1 Consider discontinuance in patients with confirmed hematologic abnormalities.1

HBV Reactivation

Reactivation of HBV infection reported in patients previously infected with the virus.1 Death reported in a few individuals.1 Use of multiple immunosuppressive agents may contribute to HBV reactivation.1

Screen at-risk patients prior to initiation of therapy.1 Evaluate and monitor patients with prior HBV infection before, during, and for up to several months after therapy.1 Safety and efficacy of concomitant antiviral therapy for prevention of HBV reactivation not established.1

Discontinue etanercept and initiate appropriate treatment (e.g., antiviral therapy) if HBV reactivation occurs.1 Not known whether etanercept can be readministered once control of a reactivated HBV infection is achieved; caution advised in this situation.1

Allergic Reactions

Possible allergic reactions.1 If serious allergic reaction or anaphylaxis occurs, immediately discontinue etanercept and initiate appropriate therapy.1

Immunization

Patients may receive inactivated vaccines.1 No data available on secondary transmission of infection with live vaccines in etanercept-treated patients.1 Avoid concurrent administration of live vaccines wtih etanercept.1

Review vaccination status and administer all age-appropriate vaccines included in current immunization guidelines, if possible, prior to initiating the drug.1

Consider risks and benefits of administering live or live-attenuated vaccines to infants exposed to the drug in utero.1

Autoimmunity

Possible formation of autoimmune antibodies.1 15 33 Lupus-like syndrome or autoimmune hepatitis reported rarely; may resolve upon discontinuance of the drug.1 If manifestations suggestive of lupus-like syndrome or autoimmune hepatitis develop, discontinue etanercept and carefully evaluate patient.1 36 48

Nonneutralizing antibodies to etanercept may develop.1 Long-term immunogenicity remains to be determined.1

Patients with Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis Receiving Immunosuppressants

Concurrent use of etanercept with immunosuppressive agents in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis not recommended.1 Increased incidence of non-cutaneous solid malignancies without improved clincial outcomes seen with the combination as compared to standard therapy alone.1

Increased Mortality in Patients with Moderate to Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis

Use in patients with moderate to severe alcoholic hepatitis associated with higher mortality rate following 6 months of use; use with caution in such patients.1

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Available studies do not reliably establish an association between etanercept and major birth defects.1

In a pregnancy registry cohort study, 9.4% of women in the etanercept-exposed cohort delivered a live-born infant with a major birth defect, compared with 3.5% of women with rheumatic diseases or psoriasis not exposed to the drug.1 In another study in pregnant women with chronic inflammatory disease, 7% of women in the etanercept-exposed cohort delivered a live-born infant with a major birth defect, compared with 4.7% of women not exposed to the drug.1 However, no pattern of major birth defects was observed in either study.1

No fetal harm or malformations observed in animal studies.1

Limited data suggest etanercept crosses placenta in small amounts.1 Clinical implications of in utero exposure are unknown.1

Lactation

Limited data indicate etanercept is distributed into human milk in low concentrations and is minimally absorbed by breast-fed infants.1 No data regarding effects of etanercept on breast-fed infants or on milk production.1 Consider benefits of breast-feeding, importance of etanercept to the woman, and potential adverse effects on the breast-fed infant from the drug or underlying maternal condition.1

Pediatric Use

Used for management of polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis in pediatric patients ≥2 years of age.1 Safety and efficacy for this indication not established in pediatric patients <2 years of age.1

Used for management of juvenile psoriatic arthritis in pediatric patients ≥2 years of age.1 Safety and efficacy for this indication not established in pediatric patients <2 years of age.1

Used for management of plaque psoriasis in pediatric patients ≥4 years of age.1 Safety and efficacy for this indication not established in pediatric patients <4 years of age.1

Consider risks and benefits of administering live or live-attenuated vaccines to infants who were exposed to etanercept in utero.1

Varicella infection associated with aseptic meningitis reported.1 If a varicella-susceptible pediatric patient has a clinically important exposure to varicella while receiving etanercept, discontinue the drug temporarily and consider use of varicella-zoster immune globulin.1

Malignancies, some fatal, reported in children, adolescents, and young adults who received TNF blocking agents.1 128

Inflammatory bowel disease reported rarely in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis receiving etanercept; the drug is not effective in the management of inflammatory bowel disease.1

Geriatric Use

No substantial differences in safety or efficacy relative to younger adults;1 61 however, insufficient experience in geriatric patients with psoriasis to determine whether they respond differently than younger adults.1

Possible increased incidence of infections in geriatric patients; use with caution.1

Hepatic Impairment

Pharmacokinetics of etanercept not formally studied in patients with hepatic impairment.1

Renal Impairment

Pharmacokinetics of etanercept not formally studied in patients with renal impairment.1

Common Adverse Effects

Adverse effects reported in >5% of patients receiving etanercept include infections and injection site reactions.1

Drug Interactions

Administered concomitantly with methotrexate, glucocorticoids, salicylates, NSAIAs, and/or analgesics in clinical studies.1

Biologic Antirheumatic Agents

Use caution when switching from one biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) to another, since overlapping biologic activity may further increase the risk of infection.142

Vaccines

Avoid concurrent administration of live vaccines.1 No data available on secondary transmission of infection by live vaccines in etanercept-treated patients.1

Review vaccination status and administer all age-appropriate vaccines, if possible, prior to initiation of therapy.1 Consider risks and benefits of administering live or live-attenuated vaccines to infants who were exposed to etanercept in utero.1

Specific Drugs

|

Drug or Test |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Abatacept |

Increased incidence of infection and serious infection, without additional clinical benefit, reported with abatacept and TNF blocking agents in rheumatoid arthritis1 127 |

Concomitant use not recommended1 127 Use caution when switching from one biologic DMARD to another, since overlapping biologic activity may further increase risk of infection142 |

|

Anakinra |

Increased incidence of serious infections and neutropenia, without additional clinical benefit, reported in rheumatoid arthritis1 |

Concomitant use not recommended1 Use caution when switching from one biologic DMARD to another, since overlapping biologic activity may further increase risk of infection142 |

|

Cyclophosphamide |

Concomitant use associated with increased incidence of solid malignant tumors without additional clinical benefit1 122 |

Concomitant use not recommended1 |

|

Methotrexate |

Pharmacokinetic interaction unlikely1 Concomitant use not associated with additive toxicity7 |

|

|

Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine |

B-cell immune response adequate in etanercept-treated psoriatic arthritis patients, although titers moderately lower and twofold increases less common than in controls1 |

Clinical importance of observed differences not known1 |

|

Rituximab |

Increased risk of serious infection reported in patients who received rituximab and subsequently received a TNF blocking agent142 |

Use caution when switching from one biologic DMARD to another, since overlapping biologic activity may further increase risk of infection142 |

|

Sulfasalazine |

Decrease in neutrophil counts reported1 |

Clinical importance unknown1 |

Etanercept Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Bioavailability following sub-Q administration is approximately 60%.31 Peak plasma concentrations achieved within 69 hours.1

Distribution

Extent

Limited data suggest etanercept crosses the placenta in small amounts.1

Limited data indicate etanercept distributes into human milk in low concentrations.1

Elimination

Half-life

68 hours in healthy adults;40 102 hours in adults with rheumatoid arthritis.1

Stability

Storage

Parenteral

Powder for Injection

2–8°C.1 Do not store under conditions of extreme heat or cold; do not freeze.1 Store in original carton to protect from light and physical damage.1 Do not shake.1

May store individual dose trays containing etanercept powder for injection and diluent at 20–25°C for a maximum single period of 14 days, with protection from light, heat, and humidity.1 Following storage at room temperature, do not return to refrigerator; discard if not used within 14 days.1

Store reconstituted solutions at 2–8°C;1 134 do not freeze or store at room temperature.1 Discard reconstituted solutions after 14 days.1

Single-use Vial, Prefilled Syringe, Prefilled Auto-injector, Prefilled Auto-injector Cartridge

2–8°C.1 Do not store under conditions of extreme heat or cold; do not freeze.1 Store in original carton to protect from light and physical damage.1 Do not shake.1

May store individual single-dose prefilled syringes, single-dose vials, single-dose prefilled cartridges, or single-dose prefilled auto-injectors at 20–25°C for a maximum single period of 14 days, with protection from light and heat.1 Following storage at room temperature, do not return to refrigerator; discard if not used within 14 days.1

Keep reusable auto-injector device at room temperature (20–25°C); do not refrigerate.1

Actions

-

Potent antagonist of TNF biologic activity.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 33

-

High binding affinity for TNF and lymphotoxin-α (TNF-β);1 2 3 4 5 6 8 9 13 33 35 37 each molecule can bind to 2 TNF molecules.33 Prevents the binding of TNF to cell surface TNF receptors, thereby blocking the biologic activity of TNF.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 33 37

-

Produced by recombinant DNA technology in a mammalian cell expression system.1

Advice to Patients

-

Provide a copy of the manufacturer’s patient information (medication guide) for etanercept to all patients with each prescription of the drug.1 128 Advise patients about potential benefits and risks of etanercept.1 128 137 138 Advise patients to read the medication guide prior to initiation of therapy and each time the prescription is refilled.1 128 137 138

-

If the patient or caregiver is to administer etanercept, provide careful instructions regarding proper dosage and administration, including proper aseptic technique, and proper disposal of needles and syringes.1

-

Increased susceptibility to infection.1 137 Stress importance of seeking immediate medical attention if signs and symptoms suggestive of infection (e.g., fever, chills, flu-like symptoms, cough, burning or pain on urination) develop.1

-

Risk of lymphoma, including hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma, leukemia, or other malignancies with TNF blocking agents.1 128 138 Inform patients and caregivers about the increased risk of cancer development in children, adolescents, and young adults, taking into account the clinical utility of TNF blocking agents, the relative risks and benefits of these and other immunosuppressive drugs, and the risks associated with untreated disease.1 128 138 Stress importance of promptly informing clinicians if signs and symptoms of malignancies (e.g., unexplained weight loss; fatigue; abdominal pain; persistent fever; night sweats; easy bruising or bleeding; swollen lymph nodes in the neck, underarm, or groin; easy bruising or bleeding; hepatomegaly or splenomegaly) occur.128 138

-

Advise patients to inform their clinician of any new or worsening medical conditions (e.g., neurologic conditions [e.g., demyelinating disorders], heart failure, autoimmune disorders [e.g., lupus-like syndrome, autoimmune hepatitis], psoriasis, cytopenias).1 128

-

Advise patients to promptly contact a clinician if manifestations of an allergic reaction (e.g., rash, facial swelling, difficulty breathing) occur.1

-

Advise patients to take the drug as prescribed and to not alter or discontinue therapy without first consulting with a clinician.128 138

-

Advise women to inform their clinicians if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1

-

Advise patients to inform their clinicians of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs, as well as any concomitant illnesses or any history of cancer, tuberculosis, HBV infection, or other chronic or recurring infections.1 137

-

Inform patients of other important precautionary information.1

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer's labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Parenteral |

For injection, for subcutaneous use |

25 mg |

Enbrel (multi-dose vial for reconstitution supplied with diluent syringe containing 1 mL sterile bacteriostatic water for injection [with benzyl alcohol 0.9%], 27-gauge ½-inch needle, plunger, and vial adapter) |

Amgen |

|

Injection, for subcutaneous use |

25 mg/0.5 mL |

Enbrel (available as single-dose prefilled syringes and single-dose vials) |

Amgen |

|

|

50 mg/mL |

Enbrel (available as single-dose prefilled syringes and single-dose prefilled auto-injectors [SureClick]) |

Amgen |

||

|

Enbrel Mini (available as single-dose prefilled cartridges for use with the AutoTouch reusable autoinjector) |

Amgen |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions July 10, 2024. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

1. Amgen. Enbrel (etanercept) prescribing information. Thousand Oaks, CA; 2023 Oct.

2. Murray KM, Dahl SL. Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (p75) Fc fusion protein (TNFR:Fc) in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Pharmacother. 1997; 31:1335-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9391689

3. Moreland LW, Baumgartner SW, Schiff MH et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with a recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (p75)-Fc fusion protein. N Engl J Med. 1997; 337:141-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9219699

4. Szekanecz Z, Koch AE, Kunkel SL et al. Cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis: potential targets for pharmacological intervention. Drugs Aging. 1998; 12:377-90. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9606615

5. Breedveld F. New tumor necrosis factor-alpha biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1998; 9:233-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9831171

6. Moreland LW, Margolies G, Heck LW Jr et al. Recombinant soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor (p80) fusion protein: toxicity and dose finding trial in refractory rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1996; 23:1849-55. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8923355

7. Weinblatt ME, Kremer JM, Bankhurst AD et al. A trial of etanercept, a recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor:Fc fusion protein, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate. N Engl J Med. 1999; 340:253-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9920948

8. O’Dell JR. Anticytokine therapy—a new era in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis? N Engl J Med. 1999; 340:310-2. Editorial.

9. Mohler KM, Torrance DS, Smith CA et al. Soluble tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptors are effective therapeutic agents in lethal endotoxemia and function simultaneously as both TNF carriers and TNF antagonists. J Immunol. 1993; 151:1548-61. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8393046

12. Beutler B, van Huffel C. Unraveling function in the TNF ligand and receptor families. Science. 1994; 264:667-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8171316

13. Nam MH, Reda D, Boujoukos AJ et al. Recombinant human dimeric tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor (TNFR:Fc): safety and pharmacokinetics in human volunteers. Clin Res. 1993; 41:249A.

14. Jacobs CA, Beckmann MP, Mohler K et al. Pharmacokinetic parameters and biodistribution of soluble cytokine receptors. Int Rev Exp Pathol. 1993; 34B:123-35.

15. Moreland LW, Schiff MH, Baumgartner SW et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999; 130:478-86. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10075615

16. Furst DE, Keystone E, Maini RN et al. Recapitulation of the round-table discussion—assessing the role of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999; 38(Suppl 2):50-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10646494

17. Moreland LW, Baumgartner SW, Tindall EA et al. Longterm safety and efficacy of TNF receptor (P75) Fc fusion protein (TNFR:FC; Enbrel) in DMARD refractory rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Arthritis Rheum. 1998; 41(Suppl):S364.

18. Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M et al. American College of Rheumatology preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995; 38:727-35. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7779114

19. Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary core set of disease activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 1993; 36:729-40. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8507213

20. Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Lange MLM et al. Should improvement in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials be defined as fifty percent or seventy percent improvement in core set measures, rather than twenty percent. Arthritis Rheum. 1998; 41:1564-70. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9751088

21. Giannini EH, Ruperto N, Ravelli A et al. Preliminary definition of improvement in juvenile arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997; 40:1202. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9214419

22. Fisher CJ, Agosti JM, Opal SM et al et al. Treatment of septic shock with the tumor necrosis factor receptor: Fc fusion protein. N Engl J Med. 1996; 334:1697-702. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8637514

24. Hochberg MC, Chang RW, Dwosh I et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1991 revised criteria for the classification of global functional status in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1992; 35:498-502. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1575785

25. Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA et al. The American Rheumatology Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988; 31:315-24. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3358796

28. De Benedetti F, Ravelli A, Martini A. Cytokines in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opinion Rheumatol. 1997; 9:428-33.

29. Lovell DJ, Giannini EH, Reiff A et al. Etanercept in children with polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:763-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10717011

30. Grom AA, Murray KJ, Luyrink L et al. Patterns of expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha, tumor necrosis factor beta, and their receptors in synovia of patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 1996; 39:1703-10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8843861

31. Lebsack ME, Hanna RK, Lange MA et al. Absolute bioavailability of TNF receptor fusion protein following subcutaneous injection in healthy volunteers. Pharmacotherapy. 1997; 17:1118-9.

33. Jarvis B, Faulds D. Etanercept: a review of its use in rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs. 1999; 57:945-66. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10400407

35. Franklin CM. Clinical experience with soluble TNF p75 receptor in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1999; 29:172-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10622681

36. Furst DE, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR et al. Building towards a consensus for the use of tumour necrosis factor blocking agents. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999; 58:725-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10577955

37. Garrison L, McDonnell ND. Etanercept: therapeutic use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999; 58(Suppl I):165-9.

38. Robak T, Gladalska A, Stepien H. The tumour necrosis factor family of receptors/ligands in the serum of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1998; 9:145-54. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9681390

39. Anon. Drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2000; 42:57-64. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10887424

40. Korth-Bradley JM, Rubin AS, Hanna RK et al. The pharmacokinetics of etanercept in healthy volunteers. Ann Pharmacother. 2000; 34:161-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10676822

48. Access to disease modifying treatments for rheumatoid arthritis patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999; 58(Suppl 1):1129-30.

51. Moreland LW, Bucy RP, Weinblatt ME. Effects of TNF receptor (P75) fusion protein (TNFR:Fc; Enbrel) on immune function. Arthritis Rheum. 1998; 41(Suppl):S59.

52. Baumgartner SW, Moreland LW, Schiff MH et al. Response of elderly patients to TNF receptor P75 FC fusion protein TNFR:FC; Enbrel). Arthritis Rheum. 1998; 41(Suppl):S59.

54. Pisetsky DS. Tumor necrosis factor blockers in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:810-1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10717018

57. Food and Drug Administration. Search orphan drug designations and approvals. From FDA website. Accessed 2024 May 21. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/opdlisting/oopd/

58. Sharp JT. Scoring radiographic abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritis. Radiol Clin North Am. 1996; 34:233-41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8633113

59. Stone JH, Uhlfelder ML, Hellmann DB et al. Etanercept combined with conventional treatment in Wegener’s granulomatosis: a six-month open-label trial to evaluate safety. Arth Rheum. 2001; 44:1149-54.

61. Fleischmann R, Moreland L, Baumgartner S et al. Response to Enbrel (etanercept) in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients over 65 years: a retrospective analysis of clinical trial results. Poster presented at 63rd annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. Boston, MA. 1999 Nov 16. Abstract No. 1657.

70. Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleishmann RM et al. A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000; 343:1586-93. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11096165

72. Mease PJ, Goffe BS, Metz J et al. Etanercept in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2000; 356:385-90. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10972371

79. Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB, Katz S et al. Etanercept for active Crohn’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2001; 121:1088-94. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11677200

80. Klareskog L, Moreland LM, Cohen SB et al. Global safety and efficacy of up to five years of etanercept (Enbrel) therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Poster presented at the American College of Rheumatology 65th National Science Meeting. San Francisco, CA: 2001 Nov 12. Abstract 150.

81. Kremer JM, Weinblatt ME, Fleischmann RM et al. Etanercept (Enbrel) in addition to methotrexate (MTX) in rheumatoid arthritis (RA): long-term observations. Poster presented at the American College of Rheumatology 65th National Science Meeting. San Francisco, CA: 2001 Nov 12. Abstract 152.

89. Ritchlin C, Haas-Smith SA, Hicks D et al. Patterns of cytokine production in psoriatic synovium. J Rheumatol. 1998; 25:1544-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9712099

97. Lovell DJ, Giannini EH, Reiff A et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of etanercept in children with polyarticular-course juvenile rheumatoid arthritis; interim results from an ongoing multicenter, open-label, extended-treatment trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003; 48:218-26. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12528122

99. Brown SL, Greene MH, Gershon SK et al. Tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy and lymphoma development: twenty-six cases reported to the Food and Drug Administration. Arthritis Rheum. 2002; 46:3151-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12483718

103. Furst DE, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR et al. Updated consensus statement on biological agents, specifically tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) blocking agents and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), for the treatment of rheumatic diseases, 2005. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005; 64:iv2-14. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16239380

105. Travers SB. Etanercept for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350: Letter.

106. Kupper TS. Etanercept for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004; 840: Reply.

107. Van den Brande JM, Braat H, van den Brink GR et al. Infliximab but not etanercept induces apoptosis in lamina propria T-lymphocytes from patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenetrology. 2003; 124:1774-85.

108. Leonardi CL, Powers JL, Matheson RT et al. Etanercept as monotherapy in patients with psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2003; 349:2014-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14627786

109. Papp KA, Tyring S, Lahfa M et al. A global phase III randomized controlled trial of etanercept in psoriasis; safety, efficacy, and effect of dose reduction. Br J Dermatol. 2005; 152:1304-12. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15948997

110. Mukhtyar C, Luqmani R. Current state of tumour necrosis factor (alpha) blockade in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005; 64 (suppl 4);iv31-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16239383

111. Anon. Drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. Treat Guide Med Lett. 2005; 3:83-90.

112. Genovese MC, Bathon JM, Fleischmann RM et al. Long-term safety, efficacy, and radiographic outcome with etanercept treatment in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005; 32:1232-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15996057

117. Klareskog L, van der Heijde D, de Jager JP et al. Therapeutic effect of the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with each treatment alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004; 363:675-81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15001324

118. Mease PJ, Kivitz AJ, Burch FX et al. Etanercept treatment of psoriatic arthritis: safety, efficacy, and effect on disease progression. Arthritis Rhuem. 2004; 50:2264-72.

119. Krueger GG, Langley RG, Finlay AY et al. Patient-reported outcomes of psoriasis improvement with etanercept therapy: results of a randomized phase III trial. Br J Dermatol. 2005; 153:1192-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16307657

120. Klareskog L, van der Heijde D, Wajdula S et al. Sustained efficacy and safety of etanercept and methotrexate, combined and alone, in RA patients: year 3 TEMPO trial results. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005; 64 (suppl III): 59. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15130901

121. Davis JC, van der Heijde DM, Braun J et al. Sustained durability and tolerability of etanercept in ankylosing spondylitis for 96 weeks. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005; 64:1557-62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15843448

122. The Wegener’s Granulomatosis Etanercept Trial (WGET) research group. Etanercept plus standard therapy for Wegener’s granulomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352:351-61. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15673801

127. Bristol-Myers Squibb. Orencia (abatacept) prescribing information. Princeton, NJ; 2023 Oct.

128. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Information for healthcare professionals: Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers (marketed as Remicade, Enbrel, Humira, Cimzia, and Simponi). FDA alert. Rockville MD; 2009 Aug 4. Available from FDA website. Accessed 2024 May 22. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170112032011/http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/ucm174474.htm

132. Amgen. Patient instructions for use of Enbrel (etanercept) single-use prefilled SureClick autoinjector. Thousand Oaks, CA; 2021 Apr.

133. Amgen. Patient instructions for use of Enbrel (etanercept) single-use prefilled syringe. Thousand Oaks, CA; 2021 Apr.

134. Amgen. Patient instructions for use of Enbrel (etanercept) multiple-use vial. Thousand Oaks, CA; 2021 Apr.

137. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: Drug labels for the tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) blockers now include warnings about infection with Legionella and Listeria bacteria. Rockville, MD; 2021 Oct. From FDA website. Accessed 2024 May 21. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm270849.htm

138. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: Safety review update on reports of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in adolescents and young adults receiving tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers, azathioprine and/or mercaptopurine. Rockville, MD; 2011 Apr 14. From FDA website. Accessed 2024 May 22. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20161022203927/http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm250913.htm

142. Janssen Biotech Inc. Simponi (golimumab) injection prescribing information. Horsham, PA; 2019 Sep.

143. UCB, Inc. Cimzia (certolizumab pegol) for subcutaneous injection prescribing information. Smyrna, GA; 2022 Dec.

144. Abbvie. Humira (adalimumab) injection prescribing information. North Chicago, IL; 2024 Feb.

145. Janssen Biotech, Inc. Remicade (infliximab) for IV injection prescribing information. Horsham, PA; 2021 Oct.

146. Lovell DJ, Reiff A, Ilowite NT et al. Safety and efficacy of up to eight years of continuous etanercept therapy in patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008; 58:1496-504. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18438876

147. Weinblatt ME, Bathon JM, Kremer JM et al. Safety and efficacy of etanercept beyond 10 years of therapy in North American patients with early and longstanding rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011; 63:373-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20957659

148. Alexeeva E, Horneff G, Dvoryakovskaya T et al. Early combination therapy with etanercept and methotrexate in JIA patients shortens the time to reach an inactive disease state and remission: results of a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2021; 19:5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33407590

149. Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Collier DH et al. Etanercept and Methotrexate as Monotherapy or in Combination for Psoriatic Arthritis: Primary Results From a Randomized, Controlled Phase III Trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019; 71:1112-1124. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30747501

150. Strand V, Mease PJ, Maksabedian Hernandez EJ et al. Patient-reported outcomes data in patients with psoriatic arthritis from a randomised trial of etanercept and methotrexate as monotherapy or in combination. RMD Open. 2021; 7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33452180

151. Davis JC Jr, Van Der Heijde D, Braun J et al. Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (etanercept) for treating ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003; 48:3230-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14613288

152. Davis JC Jr, van der Heijde DM, Braun J et al. Efficacy and safety of up to 192 weeks of etanercept therapy in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008; 67:346-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17967833

153. Lebwohl M, Blauvelt A, Paul C et al. Certolizumab pegol for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: Results through 48 weeks of a phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, etanercept- and placebo-controlled study (CIMPACT). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018; 79:266-276.e5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29660425

154. de Vries AC, Thio HB, de Kort WJ et al. A prospective randomized controlled trial comparing infliximab and etanercept in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis: the Psoriasis Infliximab vs. Etanercept Comparison Evaluation (PIECE) study. Br J Dermatol. 2017; 176:624-633. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27416891

155. Griffiths CE, Reich K, Lebwohl M et al. Comparison of ixekizumab with etanercept or placebo in moderate-to-severe psoriasis (UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3): results from two phase 3 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015; 386:541-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26072109

156. Reich K, Papp KA, Blauvelt A et al. Tildrakizumab versus placebo or etanercept for chronic plaque psoriasis (reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2): results from two randomised controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2017; 390:276-288. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28596043

157. Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis--results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014; 371:326-38. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25007392

158. Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Langley RG et al. Etanercept treatment for children and adolescents with plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358:241-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18199863

159. Langley RG, Paller AS, Hebert AA et al. Patient-reported outcomes in pediatric patients with psoriasis undergoing etanercept treatment: 12-week results from a phase III randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011; 64:64-70. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20619489

160. Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Pariser DM et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of etanercept in children and adolescents with plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 74:280-7.e1-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26775775

161. Dougados M, van der Heijde D, Sieper J et al. Symptomatic efficacy of etanercept and its effects on objective signs of inflammation in early nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014; 66:2091-102. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24891317

162. Dougados M, Tsai WC, Saaibi DL et al. Evaluation of Health Outcomes with Etanercept Treatment in Patients with Early Nonradiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2015; 42:1835-41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26276968

163. Dougados M, van der Heijde D, Sieper J et al. Effects of Long-Term Etanercept Treatment on Clinical Outcomes and Objective Signs of Inflammation in Early Nonradiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis: 104-Week Results From a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017; 69:1590-1598. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28482137

164. Levine JE, Paczesny S, Mineishi S et al. Etanercept plus methylprednisolone as initial therapy for acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2008; 111:2470-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18042798

165. Alousi AM, Weisdorf DJ, Logan BR et al. Etanercept, mycophenolate, denileukin, or pentostatin plus corticosteroids for acute graft-versus-host disease: a randomized phase 2 trial from the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network. Blood. 2009; 114:511-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19443659

166. Busca A, Locatelli F, Marmont F et al. Recombinant human soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor fusion protein as treatment for steroid refractory graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Hematol. 2007; 82:45-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16937391

167. Kennedy GA, Butler J, Western R et al. Combination antithymocyte globulin and soluble TNFalpha inhibitor (etanercept) +/- mycophenolate mofetil for treatment of steroid refractory acute graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006; 37:1143-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16699531

168. De Jong CN, Saes L, Klerk CPW et al. Etanercept for steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease: A single center experience. PLoS One. 2017; 12:e0187184. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29073260

169. Martin PJ, Rizzo JD, Wingard JR et al. First- and second-line systemic treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease: recommendations of the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012; 18:1150-63. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22510384

170. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. List of confused drug names. 2023 February. Accessed 2024 May 22.

2003. Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021; 73:924-939. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34101387

2004. Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS et al. 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network Recommendations for the Treatment of Ankylosing Spondylitis and Nonradiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019; 71:1599-1613. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31436036

2005. Singh JA, Guyatt G, Ogdie A et al. Special Article: 2018 American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation Guideline for the Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019; 71:5-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30499246

2006. Schoels MM, Aletaha D, Alasti F et al. Disease activity in psoriatic arthritis (PsA): defining remission and treatment success using the DAPSA score. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016; 75:811-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26269398

2007. Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019; 80:1029-1072. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30772098

2008. Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF et al. Joint AAD-NPF Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021; 84:432-470. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32738429

2009. Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020; 82:1445-1486. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32119894

2010. Menter A, Cordoro KM, Davis DMR et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis in pediatric patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020; 82:161-201. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31703821

2011. Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019; 80:1073-1113. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30772097

2012. Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment of Psoriasis: A Review. JAMA. 2020; 323:1945-1960. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32427307

2013. Ringold S, Angeles-Han ST, Beukelman T et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Treatment of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: Therapeutic Approaches for Non-Systemic Polyarthritis, Sacroiliitis, and Enthesitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019; 71:717-734. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31021516

2014. Ravelli A, Consolaro A, Horneff G et al. Treating juvenile idiopathic arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018; 77:819-828. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29643108

2022. Angeles-Han ST, Ringold S, Beukelman T et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Screening, Monitoring, and Treatment of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-Associated Uveitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019; 71:703-716. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31021540

2025. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Cosentyx (secukinumab) injection prescribing information. East Hanover, NJ; 2023 Nov.

2026. Eli Lilly and Company. Taltz (ixekizumab) injection prescribing information. Indianapolis, IN; 2024 Feb.

Related/similar drugs

Biological Products Related to etanercept

Find detailed information on biosimilars for this medication.

Frequently asked questions

- Does perispinal etanercept work for stroke recovery?

- What are the new drugs for rheumatoid arthritis (RA)?

- How long does it take for Enbrel (etanercept) to work?

- How long can Enbrel (etanercept) be left unrefrigerated?

- Can Enbrel (etanercept) be taken with antibiotics?

- Can you take Enbrel (etanercept) with a cold?

- What are the new drugs for plaque psoriasis?

- What are biologic drugs and how do they work?

- What biosimilars have been approved in the United States?

More about etanercept

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Reviews (324)

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Support group

- Drug class: antirheumatics

- Breastfeeding