Pindolol (Monograph)

Drug class: beta-Adrenergic Blocking Agents

Introduction

A nonselective β-adrenergic blocking agent (β-blocker).1 2 3 4

Uses for Pindolol

Hypertension

Management of hypertension (alone or in combination with other classes of antihypertensive agents).1 2 1200

β-Blockers generally not preferred for first-line therapy of hypertension according to current evidence-based hypertension guidelines, but may be considered in patients who have a compelling indication (e.g., prior MI, ischemic heart disease, heart failure) for their use or as add-on therapy in those who do not respond adequately to the preferred drug classes (ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, calcium-channel blockers, or thiazide diuretics).101 501 502 503 504 515 523 524 527 800 1200 A 2017 ACC/AHA multidisciplinary hypertension guideline states that β-blockers used for ischemic heart disease that are also effective in lowering BP include bisoprolol, carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, metoprolol tartrate, nadolol, propranolol, and timolol.1200

Individualize choice of therapy; consider patient characteristics (e.g., age, ethnicity/race, comorbidities, cardiovascular risk) as well as drug-related factors (e.g., ease of administration, availability, adverse effects, cost).501 502 503 504 515 1200 1201

The 2017 ACC/AHA hypertension guideline classifies BP in adults into 4 categories: normal, elevated, stage 1 hypertension, and stage 2 hypertension.1200 (See Table 1.)

Source: Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13-115.

Individuals with SBP and DBP in 2 different categories (e.g., elevated SBP and normal DBP) should be designated as being in the higher BP category (i.e., elevated BP).

|

Category |

SBP (mm Hg) |

DBP (mm Hg) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Normal |

<120 |

and |

<80 |

|

Elevated |

120–129 |

and |

<80 |

|

Hypertension, Stage 1 |

130–139 |

or |

80–89 |

|

Hypertension, Stage 2 |

≥140 |

or |

≥90 |

The goal of hypertension management and prevention is to achieve and maintain optimal control of BP.1200 However, the BP thresholds used to define hypertension, the optimum BP threshold at which to initiate antihypertensive drug therapy, and the ideal target BP values remain controversial.501 503 504 505 506 507 508 515 523 526 530 1200 1201 1207 1209 1222 1223 1229

The 2017 ACC/AHA hypertension guideline generally recommends a target BP goal (i.e., BP to achieve with drug therapy and/or nonpharmacologic intervention) <130/80 mm Hg in all adults regardless of comorbidities or level of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.1200 In addition, an SBP goal of <130 mm Hg generally is recommended for noninstitutionalized ambulatory patients ≥65 years of age with an average SBP of ≥130 mm Hg.1200 These BP goals are based upon clinical studies demonstrating continuing reduction of cardiovascular risk at progressively lower levels of SBP.1200 1202 1210

Other hypertension guidelines generally have based target BP goals on age and comorbidities.501 504 536 Guidelines such as those issued by the JNC 8 expert panel generally have targeted a BP goal of <140/90 mm Hg regardless of cardiovascular risk and have used higher BP thresholds and target BPs in elderly patients501 504 compared with those recommended by the 2017 ACC/AHA hypertension guideline.1200

Some clinicians continue to support previous target BPs recommended by JNC 8 due to concerns about the lack of generalizability of data from some clinical trials (e.g., SPRINT study) used to support the 2017 ACC/AHA hypertension guideline and potential harms (e.g., adverse drug effects, costs of therapy) versus benefits of BP lowering in patients at lower risk of cardiovascular disease.1222 1223 1224 1229

Consider potential benefits of hypertension management and drug cost, adverse effects, and risks associated with the use of multiple antihypertensive drugs when deciding a patient's BP treatment goal.1200 1220

For decisions regarding when to initiate drug therapy (BP threshold), the 2017 ACC/AHA hypertension guideline incorporates underlying cardiovascular risk factors.1200 1207 ASCVD risk assessment is recommended by ACC/AHA for all adults with hypertension.1200

ACC/AHA currently recommend initiation of antihypertensive drug therapy in addition to lifestyle/behavioral modifications at an SBP ≥140 mm Hg or DBP ≥90 mm Hg in adults who have no history of cardiovascular disease (i.e., primary prevention) and a low ASCVD risk (10-year risk <10%).1200

For secondary prevention in adults with known cardiovascular disease or for primary prevention in those at higher risk for ASCVD (10-year risk ≥10%), ACC/AHA recommend initiation of antihypertensive drug therapy at an average SBP ≥130 mm Hg or an average DBP ≥80 mm Hg.1200

Adults with hypertension and diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease (CKD), or age ≥65 years are assumed to be at high risk for cardiovascular disease; ACC/AHA state that such patients should have antihypertensive drug therapy initiated at a BP ≥130/80 mm Hg.1200 Individualize drug therapy in patients with hypertension and underlying cardiovascular or other risk factors.502 1200

In stage 1 hypertension, experts state that it is reasonable to initiate drug therapy using the stepped-care approach in which one drug is initiated and titrated and other drugs are added sequentially to achieve the target BP.1200 Initiation of antihypertensive therapy with 2 first-line agents from different pharmacologic classes recommended in adults with stage 2 hypertension and average BP >20/10 mm Hg above BP goal.1200

Black hypertensive patients generally tend to respond better to monotherapy with calcium-channel blockers or thiazide diuretics than to β-blockers. 85 89 90 501 504 However, diminished response to β-blockers is largely eliminated when administered concomitantly with a thiazide diuretic.500

Chronic Stable Angina

Management of chronic stable angina pectoris† [off-label].2 5 15 22 1101

β-Blockers are recommended as first-line anti-ischemic drugs in most patients with chronic stable angina; despite differences in cardioselectivity, intrinsic sympathomimetic activity, and other clinical factors, all β-blockers appear to be equally effective for this use.1101

Pindolol Dosage and Administration

General

-

Individualize dosage according to patient response and tolerance.1

-

If long-term therapy is discontinued, reduce dosage gradually over a period of about 1–2 weeks.1 (See Abrupt Withdrawal of Therapy under Cautions.)

BP Monitoring and Treatment Goals

-

Monitor BP regularly (i.e., monthly) during therapy and adjust dosage of the antihypertensive drug until BP controlled.1200

-

If unacceptable adverse effects occur, discontinue drug and initiate another antihypertensive agent from a different pharmacologic class.1216

-

If adequate BP response not achieved with a single antihypertensive agent, either increase dosage of single drug or add a second drug with demonstrated benefit and preferably a complementary mechanism of action (e.g., ACE inhibitor, angiotensin II receptor antagonist, calcium-channel blocker, thiazide diuretic).1200 1216 Many patients will require ≥2 drugs from different pharmacologic classes to achieve BP goal; if goal BP still not achieved, add a third drug.1200 1216

Administration

Oral Administration

Administer orally, usually twice daily;1 bioavailability does not appear to be affected by food.1 (See Absorption under Pharmacokinetics.)

Dosage

Adults

Hypertension

Oral

Initially, 5 mg twice daily, either alone or in combination with other antihypertensives.1 52 600 Increase dosage gradually by 10 mg daily at 3- to 4-week intervals as necessary up to 60 mg daily.1 Some experts state usual maintenance dosage range is 10–60 mg daily, given in 2 divided doses.1200

Chronic Stable Angina† [off-label]

Oral

15–40 mg daily, given in 3 or 4 divided doses.2 5 22

Prescribing Limits

Adults

Hypertension

Oral

Maximum 60 mg daily.1

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

Dosage must be modified in response to the degree of hepatic impairment.1

Cautions for Pindolol

Contraindications

-

Bronchial asthma, heart block greater than first degree, cardiogenic shock, overt cardiac failure, or severe bradycardia.1

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Heart Failure

Possible precipitation of CHF.1 2

Avoid use in patients with decompensated heart failure, may use cautiously in patients with well-compensated heart failure (e.g., those controlled with ACE inhibitors, cardiac glycosides, and/or diuretics).1

Adequate treatment (e.g., with a cardiac glycoside and/or diuretic) and close observation recommended if signs or symptoms of impending heart failure occur; if heart failure continues, discontinue therapy, gradually if possible.1

Abrupt Withdrawal of Therapy

Abrupt discontinuance of therapy is not recommended as it may exacerbate angina symptoms or precipitate MI in patients with CAD.1 Gradually decrease dosage over a period of about 1–2 weeks.1 Monitor patients carefully and advise to temporarily limit their physical activity.1 If exacerbation of angina occurs, reinstitute therapy promptly, and initiate appropriate measures for the management of unstable angina pectoris.1

Bronchospastic Disease

Possible inhibition of bronchodilation produced by endogenous catecholamines.1

Generally should not be used in patients with bronchospastic disease, but may be used with caution in patients with nonallergic bronchospasm (e.g., chronic bronchitis, emphysema).1 (See Contraindications under Cautions.)

Major Surgery

Possible risks associated with general anesthesia (e.g., severe hypotension, difficulty maintaining heart beat) due to decreased ability of the heart to respond to reflex β-adrenergic stimuli.1 Use with caution in patients undergoing major surgery involving general anesthesia.1

Diabetes and Hypoglycemia

Possible decreased signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia (e.g., tachycardia, palpitation, BP changes, tremor, feelings of anxiety, but not sweating or dizziness).1 68

Use with caution in patients with diabetes mellitus receiving hypoglycemic drugs.1

Thyrotoxicosis

Signs of hyperthyroidism (e.g., tachycardia) may be masked.1 Possible thyroid storm if therapy is abruptly withdrawn;1 carefully monitor patients having or suspected of developing thyrotoxicosis.1

Sensitivity Reactions

Anaphylactic Reactions

Possible increased reactivity to repeated, accidental, diagnostic, or therapeutic challenges with a variety of allergens while taking β-blockers in patients with a history of anaphylactic reactions to a variety of allergens.1 Such patients may be unresponsive to usual doses of epinephrine.1

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Category B.1

Lactation

Distributed into milk.1 Use not recommended.1

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy not established.1

Hepatic Impairment

Hepatic elimination; use with caution.1

Common Adverse Effects

Insomnia, dizziness, fatigue, nervousness, bizarre dreams or increased dreaming, weakness, paresthesia, edema, dyspnea, muscle pain, joint pain, chest pain, muscle cramps, nausea, abdominal discomfort, pruritus.1

Drug Interactions

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Aspirin |

Pharmacokinetic interaction unlikely1 |

|

|

Digoxin |

Possible decreases in serum digoxin concentrations 1 |

|

|

Reserpine |

Additive effects1 |

Monitor for signs of hypotension and bradycardia (e.g., vertigo, syncope, postural hypotension)1 |

|

Hypotensive agents (hydralazine, hydrochlorothiazide) |

Possible increased hypotensive effects1 |

Adjust dosage carefully1 |

|

Thioridazine |

Increased serum concentrations of thioridazine1 and metabolites; higher than expected serum concentrations of pindolol1 73 1 Increased thioridazine concentrations may cause prolongation of the QTc interval and a possible increase in the risk of serious, potentially fatal cardiac arrhythmia (e.g., torsades de pointes)73 1 |

Concomitant use is contraindicated73 |

|

Warfarin |

Pharmacokinetic interaction unlikely1 |

Pindolol Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Rapidly absorbed from the GI tract with peak plasma concentrations reached within 1–2 hours.1 2

Onset

Effect on heart rate is seen within 3 hours.2

Hypotensive effect is usually seen within 1 week, but maximum therapeutic response may not be observed until 2 weeks or longer.1

Duration

Acute hemodynamic effects persist for 24 hours after administration.2

Food

Food may increase the rate,2 but not the extent of absorption.1

Special Populations

Bioavailability may be at the lower end of the range in uremic patients;2 extent of absorption may be decreased in patients with impaired renal function.19

Distribution

Extent

Distributed into milk.1

Plasma Protein Binding

Elimination

Metabolism

Extensively metabolized in the liver (approximately 60–65%) to metabolites.1 2

Elimination Route

Excreted in urine (35–50%) unchanged.1 2 18

Half-life

Special Populations

In patients with creatinine clearances <20 mL/minute, <15% is excreted in urine unchanged.1 18 20

In patients with renal failure, plasma half-life is 3–11.5 hours.2 20

In geriatric patients, plasma half-life is 7–15 hours.1

In patients with hepatic cirrhosis, half-life is 2.5–30 hours.1

Stability

Storage

Oral

Tablets

Tight, light-resistant containers at 15–30°C.1 31

Actions

-

Inhibits response to adrenergic stimuli by competitively blocking β-adrenergic receptors within the myocardium (β1-receptors) and within bronchial and vascular smooth muscle (β2-receptors).2 4 5

-

In addition, causes slight activation of the β-receptors, making the drug a partial β-agonist.2 4 5

-

At higher than therapeutically obtained plasma concentrations, the drug has membrane-stabilizing activity or a quinidine-like effect.4

-

Decreases stress- and exercise-stimulated heart rate.1 2 4 5 Has a lesser effect on resting heart rate (usually decreasing resting heart rate only by about 4–8 bpm or not at all),1 2 4 5 15 22 slowing of conduction in the AV node,4 and cardiac output,2 4 13 22 than do β-blockers that do not possess intrinsic sympathomimetic activity (ISA).1 2 4 5 15 22

-

The precise mechanism of hypotensive effect has not been determined;1 the drug does not consistently affect cardiac output or renin release, and other mechanisms (e.g., decreased peripheral resistance) probably contribute to its hypotensive effect.1 15 16

-

May increase airway resistance,1 2 4 depending on the patient’s pretreatment sympathetic tone; patients with high pretreatment tone show a decrease in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), whereas those with low pretreatment tone may show little, if any, change in FEV1.17

Advice to Patients

-

Importance of taking pindolol exactly as prescribed.1

-

Importance of not interrupting or discontinuing therapy without consulting clinician.1

-

Importance of immediately informing clinician at the first sign or symptom of impending cardiac failure (e.g., weight gain, increased shortness of breath) or if any difficulty in breathing occurs.1

-

In patients with heart failure, importance of informing clinician of signs or symptoms of exacerbation (e.g., weight gain, difficulty in breathing).1

-

Importance of patients informing anesthesiologist or dentist that they are receiving pindolol therapy prior to undergoing major surgery.1

-

Importance of informing clinicians of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs.1

-

Importance of women informing clinicians if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1

-

Importance of informing patients of other important precautionary information.1 (See Cautions.)

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

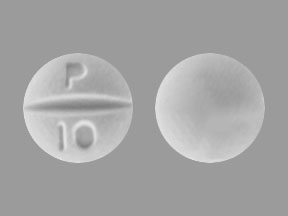

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Tablets |

5 mg* |

Pindolol Tablets |

|

|

10 mg* |

Pindolol Tablets |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions April 10, 2024. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

1. Zenith Goldline. Pindolol tablets prescribing information. Miami, FL; 1999 Jan.

2. Golightly LK. Pindolol: a review of its pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, clinical uses and adverse effects. Pharmacotherapy. 1982; 2:134-47. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6133267

3. Weber MA. Beta blockers in the initial therapy of hypertension. Drug Ther. 1980; 10(11):77-80.

4. Frishman WH. β-Adrenoceptor antagonists: new drugs and new indications. N Engl J Med. 1981; 305:500-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6114433

5. Opie LH. Drugs and the heart. Lancet. 1980; 1:693-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6103100

6. Talbert RL. Use of β-adrenergic blocking agents after myocardial infarction. Clin Pharm. 1983; 2:68-74. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6136362

7. Weber MA, Drayer JIM. Renal effects of beta-adrenoceptor blockade. Kidney Int. 1980; 13:686-99.

8. Waal-Manning HJ. Hypertension: which beta-blocker? Drugs. 1976; 12:412-41.

9. Leonard RG, Talbert RL. Calcium-channel blocking agents. Clin Pharm. 1982; 1:17-33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6764159

10. Gonasun LM. Antihypertensive effects of pindolol. Am Heart J. 1982; 104:374-87. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7048877

11. Frishman W, Jacob H, Eisenberg E et al. Clinical pharmacology of the new beta-adrenergic blocking drugs. Part 8. Self-poisoning with beta-adrenoceptor blocking agents: recognition and management. Am Heart J. 1979; 98:798-811. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40429

12. Thadani U, Davidson C, Char B et al. Comparison of the immediate effects of five β-adrenoreceptor-blocking drugs with different ancillary properties in angina pectoris. N Engl J Med. 1979; 300:750-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/581782

13. Taylor SH, Solke G, Lee PS. Intravenous β-blockade in coronary heart disease. Is cardioselectivity or intrinsic sympathomimetic activity hemodynamically useful? N Engl J Med. 1982; 306:631-5.

14. The United States pharmacopeia, 21st rev, and The national formulary, 16th ed. Rockville, MD: The United States Pharmacopeial Convention, Inc; 1987(Suppl 5):2486.

15. Frishman WH. Pindolol: a new β-adrenoceptor antagonist with partial agonist activity. N Engl J Med. 1983; 308:940-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6339926

16. Man in’t Veld AJ, Schalekamp ADH. Effects of 10 different β-adrenoreceptor antagonists on hemodynamics, plasma renin activity, and plasma norepinephrine in hypertension: the key role of peripheral vascular resistance changes in relation to partial agonist activity. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1983; 5:S30-S45.

17. Plotnick GD, Fisher ML, Hamilton JH et al. Intrinsic sympathetic activity of pindolol: evidence for interaction with pretreatment sympathetic tone. Am J Med. 1983; 74:625-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6340489

18. Sandoz Pharmaceuticals: Personal communication; 1983 Aug 1.

19. Chau NP, Weiss YA, Safar ME et al. Pindolol availability in hypertensive patients with normal and impaired renal function. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1977; 22:505-10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/913016

20. Ohnhaus EE, Heidemann H, Meier J et al. Metabolism of pindolol in patients with renal failure. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1982; 423-8.

21. Anon. Diuretic or beta-blocker as first-line treatment of mild hypertension. Lancet. 1982; 2:1316-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6128605

22. Kostis JB, Frishman W, Hosler MH et al. Treatment of angina pectoris with pindolol: the significance of intrinsic sympathomimetic activity of beta blockers. Am Heart J. 1982; 104:496-504. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7102536

23. Rangno RE, Langlois S. Comparison of withdrawal phenomena after propranolol, metoprolol, and pindolol. Am Heart J. 1982; 104:473-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7102534

24. Walden RJ, Hernandez J, Yu Y et al. Withdrawal of beta-blocking drugs. Am Heart J. 1982; 104:515-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6125098

25. Gonasun LM, Langrall H. Adverse reactions to pindolol administration. Am Heart J. 1982; 104:482-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7048882

26. Krupp P, Fanchamps A. Pindolol: experience gained in 10 years of safety monitoring. Am Heart J. 1982; 104:486-90. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7048883

27. Gold DD. Propranolol-associated hyperglycemia: a case report. Hosp Formul. 1982; 17:92-101.

28. Koda-Kimble MA, Rotblatt MD. Diabetes mellitus. In: Katcher BS, Young LY, Koda-Kimble MA, eds. Applied therapeutics: the clinical use of drugs. San Francisco: Applied Therapeutics; 1983:1396-7.

29. Heel RC, Brogden RN, Speight TM et al. Atenolol: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in hypertension. Drugs. 1979; 17:425-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38096

30. Opie LH. Drugs and the heart. Lancet. 1980; 1:693-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6103100

31. The United States Pharmacopeial Convention, Inc. Pindolol tablets. Pharmacopeial Forum. 1984; 10:4411.

33. Weinstein RS. Recognition and management of poisoning with beta-adrenergic blocking agents. Ann Emerg Med. 1984; 13:1123-31. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6150667

34. Koller W, Orebaugh C, Lawson L et al. Pindolol-induced tremor. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1987; 10:449-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3332615

35. Hod H, Har-Zahav J, Kaplinsky N et al. Pindolol-induced tremor. Postgrad Med J. 1980; 56:346-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7443595 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2425633/

36. Teravainen H, Larsen A, Fogelholm R. comparison between the effects of pindolol and propranolol on essential tremor. Neurology. 1977; 27:439-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/558548

39. Weber MA, Laragh JH. Hypertension: steps forward and steps backward: the Joint National Committee fifth report. Arch Intern Med. 1993; 153:149-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8422205

40. Collins R, Peto R, MacMahon S et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 2, short-term reductions in blood pressure: an overview of randomized drug trials in their epidemiological context. Lancet. 1990; 335:827-38. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1969567

41. Alderman MH. Which antihypertensive drugs first—and why! JAMA. 1992; 267:2786-7. Editorial.

42. MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet. 1990; 335:765-74. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1969518

43. SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension: final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA. 1991; 265:3255-64. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2046107

44. Dahlof B, Lindholm LH, Hansson L et al. Morbidity and mortality in the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension (STOP-hypertension). Lancet. 1991; 338:1281-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1682683

45. MRC Working Party. Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults: principal results. BMJ. 1992; 304:405-12. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1445513 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1995577/

46. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. NHLBI panel reviews safety of calcium channel blockers. Rockville, MD; 1995 Aug 31. Press release.

47. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. New analysis regarding the safety of calcium-channel blockers: a statement for health professionals from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Rockville, MD; 1995 Sep 1.

48. Psaty BM, Heckbert SR, Koepsell TD et al. The risk of myocardial infarction associated with antihypertensive drug therapies. JAMA. 1995; 274:620-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7637142

49. Yusuf S. Calcium antagonists in coronary artery disease and hypertension: time for reevaluation? Circulation. 1995; 92:1079-82. Editorial.

50. Ellison RH. Dear doctor letter regarding appropriate use of Posicor. Nutley, NJ: Roche Laboratories; 1997 Dec.

52. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National High Blood Pressure Education Program. The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VI). Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1997 Nov. (NIH publication No. 98-4080.)

53. Kaplan NM. Choice of initial therapy for hypertension. JAMA. 1996; 275:1577-80. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8622249

54. Psaty BM, Smith NL, Siscovich DS et al. Health outcomes associated with antihypertensive therapies used as first-line agents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 1997; 277:739-45. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9042847

55. Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Espeland MA et al. for the TONE Collaborative Research Group. Sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older persons: a randomized controlled trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly (TONE). JAMA. 1998; 279:839-46. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9515998

57. Genuth P. United Kingdom prospective diabetes study results are in. J Fam Pract. 1998; 47:(Suppl 5):S27.

59. Watkins PJ. UKPDS: a message of hope and a need for change. Diabet Med. 1998; 15:895-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9827842

60. Bretzel RG, Voit K, Schatz H et al. The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS): implications for the pharmacotherapy of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1998; 106:369-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9831300

61. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood presure control and risk of microvascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998; 317:703-13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9732337 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC28659/

62. American Diabetes Association. The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) for type 2 diabetes: what you need to know about the results of a long-term study. Washington, DC; 1998 Sep 15 from American Diabetes Association web site. http://www.dtu.ox.ac.uk/ukpds

63. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Efficacy of atenolol and captopril in reducing risk of macrovascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 39. BMJ. 1998; 317:713-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9732338 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC28660/

64. Davis TME. United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study: the end of the beginning? Med J Aust. 1998; 169:511-2.

66. Anon. Consensus recommendations for the management of chronic heart failure. On behalf of the membership of the advisory council to improve outcomes nationwide in heart failure. Part II. Management of heart failure: apporaches to the prevention of heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1999; 83:9-38A.

67. Roche. Posicor (mibefradil hydrochloride) tablets prescribing information. Nutley, NJ; 1997 Dec.

68. Lim PO, MacDonald TM. Antianginal and β-adrenergic blocking drugs. In: Dukes MNG, ed. Meyler’s side effects of drugs. 13th ed. New York: Elsevier/North Holland Inc; 1996:488-535.

69. Gress TW, Nieto FJ, Shahar E et al. Hypertension and antihypertensive therapy as risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:905-12. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10738048

70. Sowers JR, Bakris GL. Antihypertensive therapy and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:969-70. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10738057

71. Izzo JL, Levy D, Black HR. Importance of systolic blood pressure in older Americans. Hypertension. 2000; 35:1021-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10818056

72. Frohlich ED. Recognition of systolic hypertension for hypertension. Hypertension. 2000; 35:1019-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10818055

73. Novartis. Mellaril, Mellaril-S (thioridazine) tablets, oral solution, and oral suspension prescribing information. East Hanover, NJ; 2000 Jun.

74. Bakris GL, Williams M, Dworkin L et al. Preserving renal function in adults with hypertension and diabetes: a consensus approach. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000; 36:646-61. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10977801

75. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet. 1998; 351:1755-62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9635947

78. ACC/AHA/ACP-ASIM guidelines for the management of patients with chronic stable angina: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients with Chronic Stable Angina). J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999; 33:2092-7.

79. Williams CL, Hayman LL, Daniels SR et al. Cardiovascular health in childhood: a statement for health professional from the Committee on Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young (AHOY) of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002; 106:143-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12093785

82. Appel LJ. The verdict from ALLHAT—thiazide diuretics are the preferred initial therapy for hypertension. JAMA. 2002; 288:3039-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12479770

83. The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002; 288:2981-97. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12479763

85. Douglas JG, Bakris GL, Epstein M et al. Management of high blood pressure in African Americans: Consensus statement of the Hypertension in African Americans Working Group of the International Society on Hypertension in Blacks. Arch Intern Med. 2003; 163:525-41.

87. The Guidelines Subcommitee of the WHO/ISH Mild Hypertension Liaison Committee. 1999 guidelines for the management of hypertension. J Hypertension. 1999; 17:392-403.

89. Wright JT, Dunn JK, Cutler JA et al. Outcomes in hypertensive black and nonblack patients treated with chlorthalidone, amlodipine, and lisinopril. JAMA. 2005; 293:1595-607. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15811979

90. Neaton JD, Kuller LH. Diuretics are color blind. JAMA. 2005; 293:1663-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15811986

91. Thadani U. Beta blockers in hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 1983; 52:10-5D.

92. Conolly ME, Kersting F, Dollery CT. The clinical pharmacology of beta-adrenoceptor-blocking drugs. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1976; 19:203-34. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10600

93. Shand DG. State-of-the-art: comparative pharmacology of the β-adrenoceptor blocking drugs. Drugs. 1983; 25(Suppl 2):92-9.

94. Breckenridge A. Which beta blocker? Br Med J. 1983; 286:1085-8. (IDIS 169422)

95. Anon. Choice of a beta-blocker. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1986; 28:20-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2869400

96. Wallin JD, Shah SV. β-Adrenergic blocking agents in the treatment of hypertension: choices based on pharmacological properties and patient characteristics. Arch Intern Med. 1987; 147:654-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2881524

97. McDevitt DG. β-Adrenoceptor blocking drugs and partial agonist activity: is it clinically relevant? Drugs. 1983; 25:331-8.

98. McDevitt DG. Clinical significance of cardioselectivity: state-of-the-art. Drugs. 1983; 25(Suppl 2):219-26.

99. Lewis RV, McDevitt DG. Adverse reactions and interactions with β-adrenoceptor blocking drugs. Med Toxicol. 1986; 1:343-61. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2878346

100. Frishman WH. Clinical differences between beta-adrenergic blocking agents: implications for therapeutic substitution. Am Heart J. 1987; 113:1190-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2883867

101. Dahlof B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension Study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002;359:995-1003.

500. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National High Blood Pressure Education Program. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7 ). Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2004 Aug. (NIH publication No. 04-5230.)

501. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014; 311:507-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24352797

502. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2013; 31:1281-357. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23817082

503. Go AS, Bauman MA, Coleman King SM et al. An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hypertension. 2014; 63:878-85. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24243703

504. Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014; 16:14-26. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24341872

505. Wright JT, Fine LJ, Lackland DT et al. Evidence supporting a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 150 mm Hg in patients aged 60 years or older: the minority view. Ann Intern Med. 2014; 160:499-503. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24424788

506. Mitka M. Groups spar over new hypertension guidelines. JAMA. 2014; 311:663-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24549531

507. Peterson ED, Gaziano JM, Greenland P. Recommendations for treating hypertension: what are the right goals and purposes?. JAMA. 2014; 311:474-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24352710

508. Bauchner H, Fontanarosa PB, Golub RM. Updated guidelines for management of high blood pressure: recommendations, review, and responsibility. JAMA. 2014; 311:477-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24352759

515. Thomas G, Shishehbor M, Brill D et al. New hypertension guidelines: one size fits most?. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014; 81:178-88. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24591473

523. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2012; 126:e354-471.

524. WRITING COMMITTEE MEMBERS, Yancy CW, Jessup M et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013; 128:e240-327.

526. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR et al. Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014; :. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24788967

527. O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013; 127:e362-425. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3695607/

530. Myers MG, Tobe SW. A Canadian perspective on the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) hypertension guidelines. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014; 16:246-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24641124

536. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Blood Pressure Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the management of blood pressure in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012: 2: 337-414.

600. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. Pindolol tablets prescribing information. Morgantown, WV; 2010 Aug.

800. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B et al. 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update on New Pharmacological Therapy for Heart Failure: An Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2016; :. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/134/13/e282.long

1101. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2012; 126:e354-471.

1200. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018; 71:el13-e115. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29133356

1201. Bakris G, Sorrentino M. Redefining hypertension - assessing the new blood-pressure guidelines. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:497-499. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29341841

1202. Carey RM, Whelton PK, 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guideline Writing Committee. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: synopsis of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association hypertension guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018; 168:351-358. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29357392

1207. Burnier M, Oparil S, Narkiewicz K et al. New 2017 American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology guideline for hypertension in the adults: major paradigm shifts, but will they help to fight against the hypertension disease burden?. Blood Press. 2018; 27:62-65. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29447001

1209. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R et al. Pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in adults aged 60 years or older to higher versus lower blood pressure targets: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017; 166:430-437. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28135725

1210. SPRINT Research Group, Wright JT, Williamson JD et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:2103-16. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26551272

1216. Taler SJ. Initial treatment of hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:636-644. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29443671

1220. Cifu AS, Davis AM. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults. JAMA. 2017; 318:2132-2134. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29159416

1222. Bell KJL, Doust J, Glasziou P. Incremental benefits and harms of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association high blood pressure guideline. JAMA Intern Med. 2018; 178:755-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29710197

1223. LeFevre M. ACC/AHA hypertension guideline: what is new? what do we do?. Am Fam Physician. 2018; 97(6):372-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29671534

1224. Brett AS. New hypertension guideline is released. From NEJM Journal Watch website. Accessed 2018 Jun 18. https://www.jwatch.org/na45778/2017/12/28/nejm-journal-watch-general-medicine-year-review-2017

1229. Ioannidis JPA. Diagnosis and treatment of hypertension in the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines and in the real world. JAMA. 2018; 319(2):115-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29242891

1235. Mann SJ. Redefining beta-blocker use in hypertension: selecting the right beta-blocker and the right patient. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2017; 11(1):54-65. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28057444

Related/similar drugs

More about pindolol

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (3)

- Drug images

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: non-cardioselective beta blockers

- Breastfeeding

- En español