Clarithromycin (Monograph)

Brand name: Biaxin

Drug class: Other Macrolides

- Antimycobacterial Agents

Introduction

Antibacterial; macrolide antibiotic.1

Uses for Clarithromycin

Acute Otitis Media (AOM)

Treatment of AOM caused by H. influenzae, M. catarrhalis, or S. pneumoniae.1 431

Not a drug of first choice; considered an alternative for patients with a history of type I penicillin hypersensitivity.396 431 May not be effective for AOM that fails to respond to amoxicillin since S. pneumoniae resistant to amoxicillin also may be resistant to clarithromycin.423

Pharyngitis and Tonsillitis

Treatment of pharyngitis or tonsillitis caused by susceptible Streptococcus pyogenes (group A β-hemolytic streptococci).1 2 19 24 25 62 63 143 Generally effective in eradicating S. pyogenes from the nasopharynx, but efficacy in the prevention of subsequent rheumatic fever has not been established to date.1

CDC, AAP, IDSA, AHA, and others recommend oral penicillin V or IM penicillin G benzathine as treatments of choice;107 109 110 396 oral cephalosporins and oral macrolides considered alternatives.107 109 110 396 Amoxicillin sometimes used instead of penicillin V, especially for young children.109 396

Consider that strains of S. pyogenes resistant to macrolides are common in some areas of the world (e.g., Japan, Finland) and clarithromycin-resistant strains have been reported in the US.396 446 461 (See Selection and Use of Anti-infectives under Cautions.)

Respiratory Tract Infections

Treatment of acute maxillary sinusitis caused by Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, or S. pneumoniae.1 2 26 144

Treatment of acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic bronchitis caused by H. influenzae, H. parainfluenzae, M. catarrhalis, or S. pneumoniae.1 56

Treatment of mild to moderate community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) caused by H. influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae (Chlamydia pneumoniae), S. pneumoniae,1 29 30 46 47 56 96 121 130 131 132 133 H. parainfluenzae, or M. catarrhalis.1

Treatment of Legionnaires’ disease† [off-label] caused by Legionella pneumophila.13 447 448 Drugs of choice are macrolides (usually azithromycin) or fluoroquinolones with or without rifampin.13 447 448 449 450 450

Treatment of pertussis† [off-label] caused by Bordetella pertussis.393 396 452 454 Erythromycin traditionally has been drug of choice for treatment and postexposure prophylaxis of pertussis,396 452 454 but other macrolides (azithromycin, clarithromycin) appear to be as effective and may be associated with better compliance because they are better tolerated.396 452 454

Skin and Skin Structure Infections

Treatment of uncomplicated skin or skin structure infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus or S. pyogenes.1 56 57 136 137 138 139 140

Helicobacter pylori Infection and Duodenal Ulcer Disease

Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection and duodenal ulcer disease (active or 1-year history of duodenal ulcer);1 335 353 377 378 eradication of H. pylori has been shown to reduce the risk of duodenal ulcer recurrence.1 335 353 377 378

Used in a multidrug regimen that includes amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and either lansoprazole or omeprazole (triple therapy).1 335 353 377 378 393 Also used with omeprazole (dual therapy) or ranitidine bismuth citrate (dual therapy).1 324

Bartonella Infections

Treatment of infections caused by B. henselae † [off-label] (e.g., cat scratch disease, bacillary angiomatosis, peliosis hepatitis).444 465

Cat scratch disease generally self-limited in immunocompetent individuals and may resolve spontaneously in 2–4 months; some clinicians suggest that anti-infectives be considered for acutely or severely ill patients with systemic symptoms, particularly those with hepatosplenomegaly or painful lymphadenopathy, and such therapy probably is indicated in immunocompromised patients.396 465

Anti-infectives also indicated in patients with B. henselae infections who develop bacillary angiomatosis, neuroretinitis, or Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome.396

Optimum regimens have not been identified; some clinicians recommend azithromycin, clarithromycin, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, doxycycline, rifampin, co-trimoxazole, gentamicin, or third generation cephalosporins.393 396 444

Cryptosporidiosis

May decrease incidence of cryptosporidiosis† [off-label] in HIV-infected adults.105 111 204 Anti-infectives may suppress the infection, but none has been found to reliably eradicate Cryptosporidium.105 106 444 445 CDC, NIH, IDSA, and others state that the most appropriate treatment for cryptosporidiosis in HIV-infected individuals is the use of potent antiretroviral agents (to restore immune function) and symptomatic treatment of diarrhea.105 106 444 445

Lyme Disease

Alternate for treatment of early Lyme disease† [off-label].290 388 389 387 390 391 392 394 395 396 397 398 427 428 IDSA, AAP, and others recommend doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime;345 393 396 427 428 429 macrolides may be less effective than these first-line agents.290 345 388 389 390 391 392 393 394 395 396 397 398 427 428

Mycobacterial Infections

Primary prevention (primary prophylaxis) of Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) bacteremia or disseminated infections in adults, adolescents, and children with advanced HIV infection.1 201 203 204 210 293 350 Recommended by USPHS/IDSA as a drug of choice for primary prevention of MAC in HIV-infected patients.204

Treatment of disseminated MAC infection in HIV-infected adults, adolescents, and children.1 7 172 173 175 176 177 178 185 187 211 293 350 444 445 ATS, CDC, NIH, IDSA, and others recommend a regimen of clarithromycin (or azithromycin) and ethambutol and state that consideration may be given to adding a third drug (preferably rifabutin).201 215 221 350 369 393 444 445 Clarithromycin usually the preferred macrolide for initial treatment; azithromycin can be substituted if clarithromycin cannot be used because of drug interactions or intolerance and is preferred in pregnant women.444 445

Prevention of recurrence (secondary prophylaxis) of disseminated MAC infection in HIV-infected adults, adolescents, and children.1 175 177 185 204 350 444 445 USPHS/IDSA, CDC, NIH, IDSA, and others recommend a macrolide (clarithromycin or azithromycin) given with ethambutol (with or without rifabutin).204 444 445 Azithromycin usually the preferred macrolide for use in conjunction with ethambutol for secondary prophylaxis in pregnant women.204 444

Treatment of pulmonary MAC infections in HIV-negative patients†.350 451 A multiple-drug regimen of clarithromycin (or azithromycin), ethambutol, and either rifabutin or rifampin usually recommended.350

Treatment of M. kansasii infections†; an alternative agent.350 393

Treatment of cutaneous infections caused by M. abscessus or Mycobacterium chelonae †.188 350 393 462

Treatment of cutaneous M. marinum infection†.189 350 393

Toxoplasmosis

Has been used in conjunction with pyrimethamine for treatment of encephalitis caused by Toxoplasma gondii † in HIV-infected patients;2 48 444 not a preferred or alternative agent.444 445 464 CDC, NIH, IDSA, and others usually recommend pyrimethamine in conjunction with sulfadiazine and leucovorin for treatment of toxoplasmosis in adults and children, especially immunocompromised patients (e.g., HIV-infected individuals).444 445 464

Prevention of Bacterial Endocarditis

Alternative for prevention of α-hemolytic (viridans group) streptococcal endocarditis† in penicillin-allergic patients undergoing certain dental, oral, respiratory tract, or esophageal procedures who have cardiac conditions that put them at high or moderate risk.345

Consult most recent AHA recommendations for specific information on which cardiac conditions are associated with high or moderate risk of endocarditis and which procedures require prophylaxis.345

Clarithromycin Dosage and Administration

Administration

Oral Administration

Conventional tablets and oral suspension: Administer orally without regard to meals.1 2 3 Oral suspension may be administered with milk.1 2 3

Extended-release tablets: Administer orally with food.1 2 3 Should be swallowed whole and not chewed, broken, or crushed.1

Reconstitution

Reconstitute granules for oral suspension at the time of dispensing by adding the amount of water specified on the bottle in two portions; agitate well after each addition.1 Agitate well just prior to use.1

Dosage

Extended-release tablets may be used only for treatment of acute maxillary sinusitis, acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic bronchitis, and CAP in adults; safety and efficacy not established for treatment of other infections in adults or for use in pediatric patients.1

Pediatric Patients

Acute Otitis Media (AOM)

Oral

7.5 mg/kg every 12 hours for 10 days.1 431

Pharyngitis and Tonsillitis

Oral

7.5 mg/kg every 12 hours for 10 days.1

Respiratory Tract Infections

Acute Bacterial Sinusitis

Oral7.5 mg/kg every 12 hours for 10 days.1

Community-acquired Pneumonia (CAP)

Oral7.5 mg/kg every 12 hours for 10 days.1

Pertussis†

Oral15–20 mg/kg daily in 2 divided doses (up to 1 g daily) for 7 days.396 7.5 mg/kg twice daily for 7 days has been used in children 1 month to 16 years of age.454

Skin and Skin Structure Infections

Oral

7.5 mg/kg every 12 hours for 10 days.1

Bartonella Infections†

Cat Scratch Disease Caused by Bartonella henselae†

Oral500 mg daily for 4 weeks.465

Bartonella Infections in HIV-infected Individuals†

OralAdolescents: 500 mg twice daily for ≥3 months recommended by CDC, NIH, and IDSA.444 If relapse occurs, consider lifelong secondary prophylaxis (chronic maintenance therapy) with erythromycin or doxycycline.444

Lyme Disease†

Oral

7.5 mg/kg (up to 500 mg) twice daily for 14–21 days for treatment of early localized or early disseminated disease.428

Mycobacterium avium Complex (MAC) Infections

Primary Prevention of MAC in Children with Advanced HIV Infection

Oral7.5 mg/kg (up to 500 mg) every 12 hours.1 204

USPHS/IDSA recommends initiation of primary prophylaxis if CD4+ T-cell count is <750/mm3 in those <1 year, <500/mm3 in those 1–2 years, <75/mm3 in those 2–6 years, or <50/mm3 in those ≥6 years of age.204

Primary Prevention of MAC in Adolescents with Advanced HIV Infection

OralUSPHS/IDSA recommends initiation of primary prophylaxis if CD4+ T-cell count is <50/mm3.204 May be discontinued if there is immune recovery in response to antiretroviral therapy and an increase in CD4+ T-cell count to >100/mm3 sustained for ≥3 months.204 Reinitiate prophylaxis if CD4+ T-cell count decreases to <50–100/mm3.204

Treatment of Disseminated MAC in HIV-infected Children

OralManufacturer recommends 7.5 mg/kg (up to 500 mg) every 12 hours.1

CDC, NIH, and IDSA recommend 7.5–15 mg/kg (maximum 500 mg) twice daily in conjunction with ethambutol (15–25 mg/kg once daily [up to 1 g daily]) with or without rifabutin (10–20 mg/kg once daily [up to 300 mg daily]).445

Treatment of Disseminated MAC in HIV-infected Adolescents

Oral500 mg every 12 hours444 in conjunction with ethambutol (15 mg/kg daily) with or without a third drug (e.g., rifabutin 300 mg once daily) recommended by CDC, NIH, and IDSA.444 Higher dosage not recommended since such dosage has been associated with reduced survival in clinical studies.171 201 204 211 214 223 224 351

Prevention of MAC Recurrence in HIV-infected Children

Oral7.5 mg/kg (maximum 500 mg) twice daily1 204 in conjunction with ethambutol (15 mg/kg [maximum 900 mg] once daily) with or without rifabutin (5 mg/kg [maximum 300 mg] once daily).204

Secondary prophylaxis to prevent MAC recurrence in HIV-infected children usually continued for life.204 445 The safety of discontinuing secondary MAC prophylaxis in children whose CD4+ T-cell count increases in response to antiretroviral therapy has not been studied.204 445

Prevention of MAC Recurrence in HIV-infected Adolescents

Oral500 mg every 12 hours1 204 444 in conjunction with ethambutol (15 mg/kg once daily) with or without rifabutin (300 mg once daily).204 444

Secondary prophylaxis to prevent MAC recurrence usually continued for life in HIV-infected adolescents.204 USPHS/IDSA states that consideration can be given to discontinuing such prophylaxis after ≥12 months in those who remain asymptomatic with respect to MAC and have an increase in CD4+ T-cell count to >100/mm3 sustained for ≥6 months.204 444

Treatment of Cutaneous Mycobacterium abscessus Infections†

Oral15 mg/kg daily (with or without incision and drainage of lesions) has been used in children 1–15 years of age.462

Prevention of Bacterial Endocarditis†

Patients Undergoing Certain Dental, Oral, Respiratory Tract, or Esophageal Procedures

Oral15 mg/kg as a single dose given 1 hour prior to the procedure.345

Adults

Pharyngitis and Tonsillitis

Oral

250 mg every 12 hours for 10 days.1

Respiratory Tract Infections

Acute Bacterial Sinusitis

OralConventional tablets or oral suspension: 500 mg every 12 hours for 14 days.1

Extended-release tablets: 1 g (two 500-mg extended release tablets) once daily for 14 days.1

Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Bronchitis

OralConventional tablets or oral suspension: 500 mg every 12 hours for 7–14 days for H. influenzae,1 500 mg every 12 hours for 7 days for H. parainfluenzae,1 or 250 mg every 12 hours for 7–14 days for M. catarrhalis or S. pneumoniae.1

Extended-release tablets: 1 g (two 500-mg extended-release tablets) once daily for 7 days.1

Community-acquired Pneumonia (CAP)

OralConventional tablets or oral suspension: 250 mg every 12 hours for 7 days for H. influenzae or for 7–14 days for S. pneumoniae, C. pneumoniae, or M. pneumoniae.1

Extended-release tablets: 1 g (two 500-mg extended-release tablets) once daily for 7 days.1

Legionnaires’ Disease†

OralConventional tablets or oral suspension: 500 mg twice daily.447 448 Usual duration is 10 days for mild to moderate infections in immunocompetent patients;447 longer duration of treatment (3 weeks) may be necessary to prevent relapse, especially in those with more severe infections or with underlying comorbidity or immunodeficiency.447 448

Skin and Skin Structure Infections

Oral

Conventional tablets or oral suspension: 250 mg every 12 hours for 7–14 days.1

Helicobacter pylori Infection and Duodenal Ulcer Disease

Oral

Conventional tablets or oral suspension: 500 mg twice daily for 10 or 14 days given in conjunction with amoxicillin and lansoprazole (triple therapy);1 353 378 500 mg twice daily for 10 days given in conjunction with amoxicillin and omeprazole (triple therapy);377 500 mg 3 times daily for 14 days given in conjunction with omeprazole or ranitidine bismuth citrate (dual therapy).1 377

Bartonella Infections†

Cat Scratch Disease Caused by Bartonella henselae†

OralConventional tablets or oral suspension: 500 mg daily for 4 weeks.465

Bartonella Infections in HIV-infected Individuals†

OralConventional tablets or oral suspension: 500 mg twice daily for ≥3 months recommended by CDC, NIH, and IDSA.444 If relapse occurs, consider lifelong secondary prophylaxis (chronic maintenance therapy) with erythromycin or doxycycline.444

Lyme Disease†

Oral

Conventional tablets or oral suspension: 500 mg twice daily for 14–21 days for treatment of early localized or early disseminated disease.428

Mycobacterial Infections

Primary Prevention of MAC in Adults with Advanced HIV Infection

OralConventional tablets or oral suspension: 500 mg every 12 hours.1 204

USPHS/IDSA recommends initiation of primary prophylaxis if CD4+ T-cell count is <50/mm3.204 May be discontinued if there is immune recovery in response to antiretroviral therapy and an increase in CD4+ T-cell count to >100/mm3 sustained for ≥3 months.204 Reinitiate prophylaxis if CD4+ T-cell count decreases to <50–100/mm3.204

Treatment of Disseminated MAC in HIV-infected Adults

OralConventional tablets or oral suspension: 500 mg every 12 hours1 444 in conjunction with ethambutol (15 mg/kg daily) with or without a third drug (e.g., rifabutin 300 mg once daily).444 Higher dosage not recommended since such dosage has been associated with reduced survival in clinical studies.171 201 204 211 214 223 224 351

Prevention of MAC Recurrence in HIV-infected Adults

OralConventional tablets or oral suspension: 500 mg every 12 hours1 204 444 in conjunction with ethambutol (15 mg/kg once daily) with or without rifabutin (300 mg once daily).204 444

Secondary prophylaxis to prevent MAC recurrence usually continued for life in HIV-infected adults.204 USPHS/IDSA states that consideration can be given to discontinuing such prophylaxis after ≥12 months in those who remain asymptomatic with respect to MAC and have an increase in CD4+ T-cell count to >100/mm3 sustained for ≥6 months.204 444

Treatment of MAC in HIV-negative Adults†

OralConventional tablets or oral suspension: 500 mg every 12 hours in conjunction with ethambutol and rifabutin or rifampin.350

Mycobacterium abscessus or M. chelonae Infections†

OralConventional tablets or oral suspension: 0.5–1 g twice daily for 6 months.188 462

M. marinum Infections†

OralConventional tablets or oral suspension: 500 mg twice daily for at least 3 months.350

Prevention of Bacterial Endocarditis†

Patients Undergoing Certain Dental, Oral, Respiratory Tract, or Esophageal Procedures

OralConventional tablets or oral suspension: 500 mg as a single dose given 1 hour prior to the procedure.345

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

No dosage adjustment required.1 56 97 98

Renal Impairment

If Clcr <30 mL/minute, reduce dose by 50% or double dosing interval.1 2 126 Alternatively (for conventional tablets or oral suspension), 500 mg initially followed by 250 mg twice daily (if the usual dosage in adults with normal renal function is 500 mg twice daily) or 250 mg daily (if the usual dosage in adults with normal renal function is 250 mg twice daily).97 121

Geriatric Patients

No dosage adjustments except those related to renal impairment.1 97 121 126 128 (See Renal Impairment under Dosage and Administration.)

Cautions for Clarithromycin

Contraindications

-

Known hypersensitivity to clarithromycin, erythromycin, any macrolide, or any ingredient in the formulation.1 353

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Increased Mortality

Increased risk of all-cause mortality reported during long-term follow-up of patients with coronary heart disease who received a 2-week course of clarithromycin in a randomized, placebo-controlled study.467 468 469 470 Variable results regarding effect of clarithromycin on risk of death or other heart-related adverse effects reported in other limited observational studies.467 468 470 A possible mechanism by which clarithromycin may increase the risk of death in patients with cardiovascular disease unknown.467 468 470

Consider risk of all-cause mortality when weighing risks and potential benefits of the drug in all patients, particularly those with cardiovascular disease.467 468 Even if only a short course of clarithromycin is indicated, consider other available antibiotics in those with heart disease.468 Not indicated for the treatment of coronary artery disease.467

Fetal/Neonatal Morbidity

Animal studies indicate adverse effects on pregnancy outcome and/or embryofetal development.1 Use during pregnancy only when safer drugs cannot be used or are ineffective.1

Superinfection/Clostridium difficile-associated Colitis

Possible emergence and overgrowth of nonsusceptible bacteria or fungi with prolonged therapy.1 Institute appropriate therapy if superinfection occurs.1

Treatment with anti-infectives may permit overgrowth of clostridia.1 Consider Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis (antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis) if diarrhea develops and manage accordingly.1 400 401 402 403 404

Sensitivity Reactions

Hypersensitivity and Dermatologic Reactions

Possible allergic reactions (e.g., mild urticaria and skin eruptions).1 2 29 47 370 371 Severe reactions (e.g., anaphylaxis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis) reported rarely.1 370 371

General Precautions

Hepatic Effects

Severe, reversible hepatic dysfunction (including cholestasis, with or without jaundice)1 and hepatomegaly2 29 47 reported.1

Fatal hepatic failure occurred in association with serious underlying disease and/or concomitant drugs.1

Resistance in Helicobacter pylori

Increased risk of developing clarithromycin resistance if used as the sole anti-infective agent in regimens for treatment of H. pylori infection.1 If therapy fails, perform in vitro susceptibility testing.1 197 377 378 Do not use clarithromycin if H. pylori is resistant.1 197 377 378

Cardiac Effects

Ventricular tachycardia and torsades de pointes reported rarely in patients with prolonged QT intervals.1

History of Acute Porphyria

Concomitant therapy with ranitidine bismuth citrate not recommended.1

Selection and Use of Anti-infectives

To reduce development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain effectiveness of clarithromycin and other antibacterials, use only for treatment or prevention of infections proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria.1

When selecting or modifying anti-infective therapy, use results of culture and in vitro susceptibility testing.1 In the absence of such data, consider local epidemiology and susceptibility patterns when selecting anti-infectives for empiric therapy.1

Consider that S. pyogenes (group A β-hemolytic streptococci) resistant to clarithromycin have been reported.396 446 461

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Category C.1 (See Fetal/Neonatal Morbidity under Cautions.)

Lactation

Distributed into milk following oral administration.460 Use with caution.1

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy not established in children <6 months of age.1

Manufacturer states safety not established in children <20 months of age with MAC infection,1 but USPHS/IDSA recommends use of the drug for HIV-infected infants and children.204

Geriatric Use

Adverse effect profile similar to that in younger adults.1 121 126

Dosage adjustment based solely on age not required.1 97 121 126 128

Clearance may be reduced due to age-related decreases in renal function.97 98 Consider need for dosage adjustment in those with severe renal impairment. (See Renal Impairment under Dosage and Administration.)

Renal Impairment

Increased half-life.1 2 56 97 98 Dosage adjustment may be necessary.1 2 126 (See Renal Impairment under Dosage and Administration.)

Concomitant therapy with ranitidine bismuth citrate not recommended if Clcr <25 mL/minute.1

Common Adverse Effects

GI adverse effects (diarrhea, nausea, abnormal taste, dyspepsia, abdominal pain) and headache.1

Drug Interactions

Clarithromycin is metabolized by and inhibits CYP3A4.1

Drugs Affecting or Metabolized by Hepatic Microsomal Enzymes

Pharmacokinetic interactions with substrates, inhibitors, or inducers of CYP3A4 are likely.1

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Amprenavir |

Increased amprenavir concentrations and AUC;437 438 439 possible decreased clarithromycin concentrations and decreased 14-hydroxyclarithromycin concentrations and AUC439 |

|

|

Anticoagulants, oral |

Increased anticoagulant effect1 |

Monitor PT carefully1 |

|

Antihistamines (astemizole, terfenadine) |

Increased plasma concentrations of astemizole or terfenadine; prolonged QT interval and serious cardiac arrhythmias 1 150 154 155 157 158 159 161 162 163 164 166 167 352 |

|

|

Antimycobacterials (rifabutin) |

Potential inhibition of rifabutin metabolism373 and induction of clarithromycin metabolism;227 373 possible increased incidence of uveitis with concomitant rifabutin and clarithromycin 373 374 375 376 |

|

|

Atazanavir |

Increased atazanavir plasma concentrations;430 increased clarithromycin plasma concentrations and decreased 14-hydroxyclarithromycin plasma concentrations;430 437 increased clarithromycin concentrations may cause QTc prolongation430 437 |

Consider reducing clarithromycin dosage by 50%;430 437 consider alternative to clarithromycin430 437 for indications other than Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC)430 |

|

Benzodiazepines (alprazolam, midazolam, triazolam) |

Potential decreased clearance of midazolam or triazolam and increased pharmacologic effects of the benzodiazepines1 Somnolence and confusion reported with clarithromycin and triazolam1 |

|

|

Carbamazepine |

Increased carbamazepine plasma concentrations and carbamazepine toxicity (i.e., drowsiness, dizziness, ataxia)2 51 338 |

Use with caution; consider reducing carbamazepine dosage and/or monitoring plasma carbamazepine concentrations1 338 |

|

Cisapride |

Increased cisapride plasma concentrations;339 prolonged QT interval and serious cardiac arrhythmias; some fatalities1 |

Contraindicated1 |

|

Colchicine |

Possible increased risk of colchicine toxicity when used concomitantly with clarithromycin, especially in elderly patients and/or patients with renal impairment1 463 |

Some clinicians state colchicine and clarithromycin should not be used concomitantly463 |

|

Darifenacin |

Possible pharmacokinetic interaction455 |

Manufacturer of darifenacin states darifenacin dosage should not exceed 7.5 mg daily in patients receiving a potent CYP3A4 inhibitor (e.g., clarithromycin)455 |

|

Delavirdine |

Increased clarithromycin concentrations and AUC;112 437 increased delavirdine concentrations437 |

Dosage adjustment not needed in those with normal renal function;112 437 reduce clarithromycin dosage by 50% if Clcr is 30–60 mL/minute; reduce clarithromycin dosage by 75% if Clcr is <30 mL/minute112 |

|

Didanosine |

No clinically important pharmacokinetic interactions 1 |

|

|

Digoxin |

Increased serum digoxin concentrations and digoxin toxicity (including potentially fatal arrhythmias)1 |

Monitor serum digoxin concentrations carefully1 |

|

Disopyramide |

Potential increased half-life of disopyramide340 and risk of prolonged QT interval and serious cardiac arrhythmias1 340 |

Monitor ECGs and serum disopyramide concentrations1 |

|

Efavirenz |

Decreased clarithromycin AUC and peak plasma concentrations;435 437 increased 14-hydroxyclarithromycin AUC and peak plasma concentrations;435 no effect on AUC of efavirenz;435 rash reported with concomitant administration435 |

Dosage adjustment of efavirenz not recommended; monitor for efficacy of the macrolide437 or consider use of an alternative anti-infective435 437 |

|

Ergot alkaloids (ergotamine, dihydroergotamine) |

Acute ergot toxicity (vasospasm and ischemia of extremities and other tissues, including CNS)1 225 |

Concomitant use contraindicated1 |

|

Erlotinib |

Possible pharmacokinetic interaction456 |

Manufacturer of erlotinib recommends caution in patients receiving a potent CYP3A4 inhibitor (e.g., clarithromycin);456 consider reducing erlotinib dosage if severe adverse effects occur456 |

|

Eszopiclone |

Possible pharmacokinetic interaction457 |

Manufacturer of eszopiclone recommends eszopiclone dosage be reduced in patients receiving a potent CYP3A4 inhibitor (e.g., clarithromycin);457 initial eszopiclone dosage should be <1 mg, but may be increased to 2 mg if clinically indicated457 |

|

Fluconazole |

Increased clarithromycin plasma concentrations1 |

|

|

Fosamprenavir |

Studies using amprenavir indicate possible increased amprenavir concentrations and AUC437 440 |

Not considered clinically important;441 dosage adjustments not recommended437 |

|

Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors |

Increased HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor plasma concentrations and potential for rhabdomyolysis1 |

|

|

Indinavir |

Increased indinavir and clarithromycin concentrations437 443 |

Indinavir manufacturer states appropriate dosages for concomitant use with respect to safety and efficacy not established;443 some experts state dosage adjustments not needed437 |

|

Lopinavir |

Reduce clarithromycin dosage by 50% if Clcr is 30–60 mL/minute; reduce clarithromycin dosage by 75% if Clcr is <30 mL/minute433 |

|

|

Nevirapine |

Decreased clarithromycin AUC and peak plasma concentration;436 437 increased 14-hydroxyclarithromycin AUC and peak plasma concentration;436 increased nevirapine concentrations437 |

Monitor for efficacy of the macrolide or use an alternative anti-infective436 437 |

|

Omeprazole |

Increased concentrations of clarithromycin, 14-hydroxyclarithromycin, and omeprazole194 196 |

|

|

Pimozide |

Potential increased pimozide plasma concentrations and risk of prolonged QT interval and serious cardiac arrhythmias1 271 272 |

|

|

Quinidine |

Risk of prolonged QT interval and serious cardiac arrhythmias1 |

Monitor ECGs and serum quinidine concentrations1 |

|

Ranitidine |

Increased plasma ranitidine concentrations and increased 14-hydroxyclarithromycin concentrations;1 not considered clinically important1 |

|

|

Ritonavir |

Increased AUC and peak plasma concentration of ritonavir and of clarithromycin;1 434 decreased AUC and peak plasma concentration of 14-hydroxyclarithromycin1 434 |

Dosage adjustment not needed in patients with normal renal function; reduce clarithromycin dosage by 50% if Clcr is 30–60 mL/minute; reduce clarithromycin dosage by 75% if Clcr is <30 mL/minute1 434 |

|

Saquinavir |

Increased clarithromycin AUC and plasma concentrations; decreased 14-hydroxyclarithromycin AUC; increased AUC and plasma concentrations of saquinavir432 437 442 |

Dosage adjustments may not be needed437 if used concomitantly for a limited time432 442 For those receiving ritonavir-boosted saquinavir, manufacturer of saquinavir states modification of dosage not necessary in those with normal renal function but clarithromycin dosage should be reduced 50% in those with Clcr 30–60 mL/minute and reduced 75% in those with Clcr <30 mL/minute432 442 |

|

Sildenafil |

Potential increased exposure to sildenafil1 |

Consider reducing sildenafil dosage1 |

|

Theophylline |

Monitor serum theophylline concentrations in those receiving high theophylline dosage or with baseline in the upper therapeutic range;1 adjust theophylline dosage as needed when clarithromycin is initiated or discontinued121 126 |

|

|

Zidovudine |

Clarithromycin Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Rapidly absorbed from GI tract.1 2 56 97 98 With conventional tablets or oral suspension, peak serum concentrations within 1–4 hours.2 56 With extended-release tablets, peak serum concentrations within 5–8 hours.1

Absolute bioavailability of conventional tablets is about 50–55%;1 2 53 56 98 absolute bioavailability may be an underestimate of systemic activity because of rapid first-pass metabolism and an active metabolite (14-hydroxyclarithromycin).98

Food

With conventional tablets, food causes a slight delay in onset of clarithromycin absorption but extent of absorption is unaffected.1 56 With extended-release tablets, food increases the extent of absorption by 30%.1

Distribution

Extent

Clarithromycin and 14-hydroxyclarithromycin distributed into most body tissues and fluids1 2 54 55 56 68 in concentrations greater than serum concentrations.1 56 68

Distributed into CSF following oral administration.458

Not known whether clarithromycin is distributed into milk.1

Plasma Protein Binding

Elimination

Metabolism

Extensively metabolized in the liver, principally by oxidative N-demethylation and hydroxylation.98 At least 7 metabolites identified; 14-hydroxyclarithromycin is the principal metabolite in serum and the only one with substantial antibacterial activity.1 2 3 4 56 97

Elimination Route

Eliminated by both renal and nonrenal mechanisms;1 2 3 56 97 98 approximately 38% of a dose excreted in urine and 40% in feces.1 2 4 126

Half-life

Special Populations

Renal impairment decreases clearance of clarithromycin and 14-hydroxyclarithromycin.1 2 56 70 97 98

Hepatic impairment reduces formation of the active metabolite; however, an increase in renal clearance of the parent drug obviates the need for a dosage reduction unless renal impairment also is present.1 56 97 98

Stability

Storage

Oral

For Suspension

Granules for oral suspension: Tight container at 15–30°C.1 Following reconstitution, do not refrigerate.1

Tablets

Conventional 250-mg tablets: Tight, light-resistant container at 15–30°C and protect from light.1

Conventional 500-mg tablets: Tight container at 20–25°C.1

Extended-release tablets: 20–25°C (may be exposed to 15–30°C).1

Clarithromycin Combinations

Kit containing clarithromycin, amoxicillin, and lansoprazole: 20–25°C.353

Actions and Spectrum

-

Usually bacteriostatic,2 12 83 84 85 but may be bactericidal against highly susceptible organisms or when present in high concentrations.2 12 84 92 94

-

Like other macrolides, inhibits protein synthesis in susceptible organisms by binding to 50S ribosomal subunits.1 2 56

-

Spectrum of activity includes many gram-positive1 2 80 83 84 85 86 92 94 95 and -negative1 2 12 16 18 56 80 83 84 85 86 92 96 aerobic bacteria, many anaerobic bacteria,1 83 121 some mycobacteria,2 32 34 35 36 77 86 87 88 and some other organisms including Mycoplasma,2 37 47 76 93 Ureaplasma,2 37 76 93 Chlamydia,1 2 17 38 39 56 61 91 96 Toxoplasma,2 41 42 43 and Borrelia.97 104

-

In vitro activity similar to75 84 86 92 or greater than that of erythromycin against erythromycin-susceptible organisms.2 56 83 94

-

The principal metabolite (14-hydroxyclarithromycin) has clinically important antimicrobial activity.1

-

Gram-positive aerobes: Active in vitro and in clinical infections against Staphylococcus aureus,1 S. pneumoniae,1 and S. pyogenes (group A β-hemolytic streptococci),1 Enterococci (e.g., Enterococcus faecalis) and oxacillin-resistant (methicillin-resistant) staphylococci are resistant.1

-

Gram-negative aerobes: Active in vitro and in clinical infections against Haemophilus influenzae,1 H. parainfluenzae,1 and Moraxella catarrhalis.1

-

Other organisms: Active in vitro and in clinical infections against C. pneumoniae and 1 M. pneumoniae.1 Also active against MAC.1

-

Organisms resistant to erythromycin generally resistant to clarithromycin.2 45

-

Complete cross-resistance occurs between azithromycin and clarithromycin in MAC.350

Advice to Patients

-

Advise patients that antibacterials (including clarithromycin) should only be used to treat bacterial infections and not used to treat viral infections (e.g., the common cold).1

-

Importance of completing full course of therapy, even if feeling better after a few days.1

-

Advise patients that skipping doses or not completing the full course of therapy may decrease effectiveness and increase the likelihood that bacteria will develop resistance and will not be treatable with clarithromycin or other antibacterials in the future.1

-

Importance of taking clarithromycin extended-release tablets with food;1 clarithromycin immediate-release tablets and oral suspension can be taken without regard to meals.1

-

Advise patients of the importance of informing clinician if they have heart disease, especially when an anti-infective is being prescribed, and the importance of seeking medical attention if they experience symptoms of a heart attack or stroke (e.g., chest pain, shortness of breath, pain or weakness in one part or side of the body, slurred speech).468

-

Importance of reporting persistent or worsening symptoms of infection.1

-

Importance of not refrigerating oral suspension.1

-

Importance of discontinuing therapy and informing clinician if an allergic reaction occurs.1

-

Importance of informing clinician of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs, as well as any concomitant illnesses.1

-

Importance of women informing clinicians if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1

-

Importance of advising patients of other important precautionary information.1 (See Cautions.)

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer’s labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

For suspension |

125 mg/5 mL* |

Clarithromycin for Suspension |

|

|

250 mg/5 mL* |

Clarithromycin for Suspension |

|||

|

Tablets, film-coated |

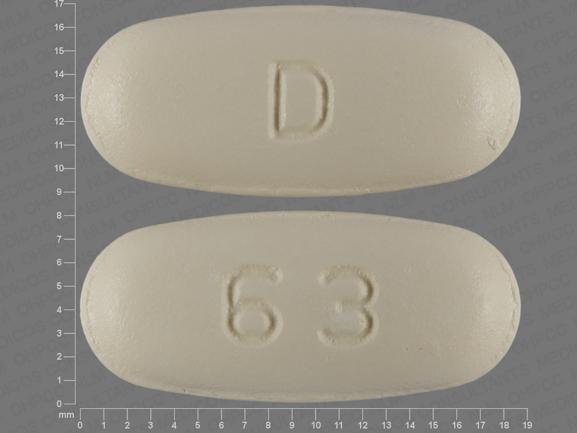

250 mg* |

Biaxin Filmtab |

AbbVie |

|

|

Clarithromycin Tablets |

||||

|

500 mg* |

Biaxin Filmtab |

AbbVie |

||

|

Clarithromycin Tablets |

||||

|

Tablets, extended-release, film-coated |

500 mg* |

Clarithromycin Tablets Extended-release |

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Kit |

4 Capsules, Amoxicillin (trihydrate) 500 mg (of amoxicillin) (Trimox) 2 Capsules, delayed-release (containing enteric-coated granules), Lansoprazole, 30 mg (Prevacid) 2 Tablets, film-coated, Clarithromycin, 500 mg (Biaxin Filmtab) 4 Capsules, Amoxicillin (trihydrate) 500 mg (of amoxicillin) 2 Capsules, delayed-release (containing enteric-coated granules), Lansoprazole, 30 mg 2 Tablets, film-coated, Clarithromycin, 500 mg |

Prevpac |

Takeda Pharmaceuticals |

|

Amoxicillin, Clarithromycin, and Lansoprazole |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions December 10, 2024. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

1. Abbott Laboratories. Biaxin (clarithromycin) Filmtab tablets, XL Filmtab extended-release tablets, and granules for oral suspension prescribing information. North Chicago, IL; 2005 Jan.

2. Piscitelli SC, Danziger LH, Rodvold KA. Clarithromycin and azithromycin: new macrolide antibiotics. Clin Pharm. 1992; 11:137-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1312921

3. Abbott Laboratories. Biaxin (clarithromycin) product information. North Chicago, IL; 1992 Feb.

4. Ferrero JL, Bopp BA, Marsh KC et al. Metabolism and disposition of clarithromycin in man. Drug Metab Dispos. 1990; 18:441-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1976065

5. Hanson CW, Bailer R, Gade E et al. Regression analysis, proposed interpretative zone size standards, and quality control guidelines for a new macrolide antimicrobial agent, A-56268 (TE-031). J Clin Microbiol. 1987; 25:1079-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2954995 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC269140/

6. American Thoracic Society. Guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Diagnosis, assessment of severity, antimicrobial therapy, and prevention. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2001; 163:1730-54. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11401897

7. Dautzenberg B, Truffot C, Legris S et al. Activity of clarithromycin against Mycobacterium avium infection in patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome: a controlled clinical trial. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991; 144(3 Part 1):564-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1832527

8. Saint-Marc T, Touraine JL. Clinical experience with a combination of clarithromycin and clofazimine in the treatment of disseminated M. avium infections in AIDS patients. Proceedings of ICAAC Chicago 1991. Abstract No. 237.

9. Dautzenberg B, St. Marc T, Averous V et al. Clarithromycin-containing regimens in the treatment of 54 AIDS patients with disseminated Mycobacterium avium intracellulare infection. Proceedings of ICAAC Chicago 1991. Abstract No. 293.

10. Kirst HA, Sides GD. New directions for macrolide antibiotics: structural modifications and in vitro activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989; 33:1413-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2684004 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC172675/

11. Omura S, Tsuzuki K, Sunazuka T et al. Macrolides with gastrointestinal motor stimulating activity. J Med Chem. 1987; 30:1941-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3669001

12. Fernandes PB, Bailer R, Swanson R et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of A-56268 (TE-031), a new macrolide. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986; 30:865-73. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2949695 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC180609/

13. Bartlett JG, Dowell SF, Mandell LA et al. Practice guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2000; 31:347-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10987697

14. Steigbigel NH. Erythromycin, lincomycin, and clindamycin. In: Mandell GL, Douglas RG Jr, Bennett JE, eds. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. 3rd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone Inc; 1991:308-17.

15. Benson CA, Segreti J, Beaudette FE et al. In vitro activity of A-56268 (TE-031), a new macrolide, compared with that of erythromycin and clindamycin against selected gram-positive and gram-negative organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987; 31:328-30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2952063 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC174717/

16. Hardy DJ, Hensey DM, Beyer JM et al. Comparative in vitro activities of new 14-, 15-, and 16-membered macrolides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988; 32:1710-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3252753 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC175956/

17. Chin NX, Neu NM, Labthavikul P et al. Activity of A-56268 compared with that of erythromycin and other oral agents against aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987; 31:463-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2953303 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC174754/

18. Barry AL, Jones RN, Thornsberry C. In vitro activities of azithromycin (CP 62,993), clarithromycin (A-56268; TE-031), erythromycin, roxithromycin, and clindamycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988; 32:752-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2840016 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC172265/

19. Scaglione F. Comparison of the clinical and bacteriological efficacy of clarithromycin and erythromycin in the treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 1990; 12:25-33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2140547

20. Marchi E. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of clarithromycin and amoxycillin in the treatment of out-patients with acute maxillary sinusitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 1990; 12:19-24. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2140546

21. Fraschini F. Clinical efficacy and tolerance of two new macrolides, clarithromycin and josamycin, in the treatment of patients with acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. J Int Med Res. 1990; 18:171-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2140331

22. Straneo G, Scarpazza G. Efficacy and safety of clarithromycin versus josamycin in the treatment of hospitalized patients with bacterial pneumonia. J Int Med Res. 1990; 18:164-70. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2140330

23. Hamedani P, Ali J, Hafeez S et al. The safety and efficacy of clarithromycin in patients with Legionella pneumonia. Chest. 1991; 100:1503-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1835689

24. Levenstein JH. Clarithromycin versus penicillin in the treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991; 27(Suppl A):67-74. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1827104

25. Bachand RT Jr. A comparative study of clarithromycin and penicillin VK in the treatment of outpatients with streptococcal pharyngitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991; 27(Suppl A):75-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1827105

26. Karma P, Pukander J, Penttila M et al. The comparative efficacy and safety of clarithromycin and amoxycillin in the treatment of outpatients with acute maxillary sinusitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991; 27(Suppl A):83-90. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1827106

27. Bachand RT Jr. Comparative study of clarithromycin and ampicillin in the treatment of patients with acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991; 27(Suppl A):91-100. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1827107

28. Aldons PM. A comparison of clarithromycin with ampicillin in the treatment of outpatients with acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991; 27(Suppl A):101-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1827095

29. Poirier R. Comparative study of clarithromycin and roxithromycin in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991; 27(Suppl A):109-16. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1827096

30. Anderson G, Esmonde TS, Coles S et al. A comparative safety and efficacy study of clarithromycin and erythromycin stearate in community-acquired pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991; 27(Suppl A):117-24. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1827098

31. Hardy DJ, Swanson RN, Rode RA et al. Enhancement of the in vitro and in vivo activities of clarithromycin against Haemophilus influenzae by 14-hydroxy-clarithromycin, its major metabolite in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990; 34:1407-13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2143642 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC175991/

32. Gelber RH, Siu P, Tsang M et al. Activities of various macrolide antibiotics against Mycobacterium leprae infection in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991; 35:760-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1648889 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC245094/

33. Franzblau SG, Hastings RC. In vitro and in vivo activities of macrolides against Mycobacterium leprae . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988; 32:1758-62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3072920 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC176013/

34. Ji B, Perani EG, Grosset JH. Effectiveness of clarithromycin and minocycline alone and in combination against experimental Mycobacterium leprae infection in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991; 35:579-81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1828136 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC245054/

35. Fernandes PB, Hardy DJ, McDaniel D et al. In vitro and in vivo activities of clarithromycin against Mycobacterium avium . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989; 33: 1531-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2530933 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC172696/

36. Naik S, Ruck R. In vitro activities of several new macrolide antibiotics against Mycobacterium avium complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989; 33:1614-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2817858 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC172713/

37. Waites KB, Cassell GH, Canupp KC et al. In vitro susceptibilities of mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas to new macrolides and aryl-fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988; 32:1500-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2973283 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC175906/

38. Bowie WR, Shaw CE, Chan DG et al. In vitro activity of Ro 15-8074, Ro 19-5247, A-56268, and roxithromycin (RU 28965) against Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987; 31:470-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2953304 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC174756/

39. Segreti J, Kessler HA, Kapell KS et al. In vitro activity of A-56268 (TE-031) and four other antimicrobial agents against Chlamydia trachomatis . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987; 31:100-1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2952061 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC174660/

40. Hardy DJ, Hanson CW, Hensey DM et al. Susceptibility of Campylobacter pylori to macrolides and fluoroquinolones. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988; 22: 631-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3209524

41. Derouin F, Chastang C. Activity in vitro against Toxoplasma gondii of azithromycin and clarithromycin alone and with pyrimethamine. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990; 25:708-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2161824

42. Chamberland S, Kirst HA, Current WL. Comparative activity of macrolides against Toxoplasma gondii demonstrating utility of an in vitro microassay. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991; 35:903-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1854172 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC245127/

43. Chang HR, Pecherè JC. In vitro effects of four macrolides (roxithromycin, spiramycin, azithromycin [CP-62,993], and A-56268) on Toxoplasma gondii . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988; 32:524-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2837140 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC172214/

44. Leclercq R, Courvalin P. Intrinsic and unusual resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogrammin antibiotics in bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991; 35:1273-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1929281 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC245157/

45. Leclercq R, Courvalin P. Bacterial resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogrammin antibiotics by target modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991; 35:1267-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1929280 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC245156/

46. Chien SM, Pichotta P, Siepman N et al. Treatment of community acquired pneumonia: a randomized, controlled trial comparing clarithromycin and erythromycin. Proceedings of ICAAC Chicago 1991. Abstract No. 872.

47. Cassell GH, Drnec J, Waites KB et al. Efficacy of clarithromycin against Mycoplasma pneumoniae . J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991; 27(Suppl A):47-59. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1827102

48. Fernandez-Martin J, Leport C, Morlat P et al. Pyrimethamine-clarithromycin combination for therapy of acute toxoplasma encephalitis in patients with AIDS. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991; 35:2049-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1836943 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC245324/

49. Nellans HN, Petersen AC, Peeters TL. Gastrointestinal side effects: clarithromycin superior to azithromycin in reduced smooth muscle contraction and binding. Proceedings of ICAAC Chicago 1991. Abstract No. 518.

50. Ruff F, Chu SY, Sonders RC et al. Effect of multiple doses of clarithromycin on the pharmacokinetics of theophylline. Proceedings of ICAAC Atlanta 1990. Abstract 761.

51. Richens A, Chu SY, Sennello LT et al. Effect of multiple doses of clarithromycin on the pharmacokinetics of carbamazepine. Proceedings of ICAAC Atlanta 1990. Abstract 760.

52. Polis MA, Haneiwich S, Kovacs JA et al. Dose escalation study to determine the safety, maximally tolerated dose, and pharmacokinetics of clarithromycin with zidovudine in HIV-infected persons. Proceedings of ICAAC Chicago 1991. Abstract 238.

53. Chu SY, Wilson DS, Eason C et al. Single- and multi-dose pharmacokinetics of clarithromycin. Proceedings of ICAAC Atlanta 1990. Abstract 759.

54. Fraschini F, Scaglione F, Pintucci G et al. The diffusion of clarithromycin and roxithromycin into nasal mucosa, tonsil and lung in humans. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991; 27(Suppl A):61-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1827103

55. Kohno Y, Ohta K, Suwa T et al. Autobacteriographic studies of clarithromycin and erythromycin in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990; 34:562-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2140497 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC171644/

56. Neu HC. The development of macrolides: clarithromycin in perspective. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991; 27(Suppl A):1-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1827094

57. Janousky S, Northcutt VJ, Craft JC. Comparative safety and efficacy of clarithromycin and reference suspensions in the treatment of children with mild to moderate skin or skin structure infections. Proceedings of ICAAC Chicago 1991. Abstract No. 870.

58. Olsson-Liljequist B, Hoffman BM. In-vitro activity of clarithromycin combined with its 14-hydroxy metabolite A-62671 against Haemophilus influenzae . J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991; 27(Suppl A):11-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1827097

59. Dabernat H, Delmas C, Seguy M et al. The activity of clarithromycin and its 14-hydroxy metabolite against Haemophilus influenzae, determined by in-vitro and serum bactericidal tests. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991; 27(Suppl A):19-30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1827099

60. Valleé E, Azoulay-Dupuis E, Swanson R et al. Individual and combined activities of clarithromycin and its 14-hydroxy metabolite in a murine model of Haemophilus influenzae infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991; 27(Suppl A):31-41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1827100

61. Ridgway GL, Mumtaz G, Fenelon L. The in-vitro activity of clarithromycin and other macrolides against the type strain of Chlamydia pneumoniae (TWAR). J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991; 27(Suppl A):43-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1827101

62. Janousky S, Northcutt VJ, Craft JC. Comparative safety and efficacy of clarithromycin and penicillin V suspensions in the treatment of children with streptococcal pharyngitis. Proceedings of ICAAC Chicago 1991. Abstract No. 871.

63. Still JG, Hubbard WC, Poole JM et al. Randomized comparison of clarithromycin and penicillin V suspensions in the treatment of children with streptococcal pharyngitis and/or tonsillitis. Proceedings of ICAAC Chicago 1991. Abstract No. 873.

64. Wood MJ. More macrolides: some may be improvement on erythromycin. BMJ. 1991; 303:594-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1932896 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1671102/

65. Chu SY, Park Y, Wilson DS et al. Pharmacokinetics of clarithromycin after 250 mg BID dosing of a suspension formulation. Proceedings of ICAAC Chicago 1991. Abstract No. 516.

66. Moellering RC Jr. Principles of anti-infective therapy. In: Mandell GL, Douglas RG Jr, Bennett JE, eds. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. 3rd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone Inc; 1991:206-18.

67. Fraschini F, Scaglione F, Pintucci JP et al. Clarithromycin and its 14-OH-metabolite. Pharmacokinetics and tissues distribution in humans. Proceedings of ICAAC Chicago 1991. Abstract No. 512.

68. Kohno Y, Yoshida H, Suwa T et al. Comparative pharmacokinetics of clarithromycin (TE-031), a new macrolide antibiotic, and erythromycin in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989; 33:751-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2526615 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC172527/

69. Chu SY, Cavanaugh J, Guay D. Pharmacokinetics of clarithromycin and 14-OH-clarithromycin following oral administration of clarithromycin 500 mg tablet. Proceedings of ICAAC Chicago 1991. Abstract No. 513.

70. Chu SY, Sunnello LT, Bunnell ST. Pharmacokinetics of clarithromycin in subjects with varying renal function. Proceedings of ICAAC Chicago 1991. Abstract No. 514.

71. Gan VN, Chu SY, Kusmiesz HT et al. Single & multi-dose pharmacokinetics in children of clarithromycin granules for suspension. Proceedings of ICAAC Chicago 1991. Abstract No. 517.

72. Zundörf H, Wishchmann L, Fassender M et al. Pharmacokinetics of clarithromycin and possible with H2 blocker and antacids. Proceedings of ICAAC Chicago 1991. Abstract No. 515.

73. Kohno Y, Yoshida H, Suwa T et al. Uptake of clarithromycin by rat lung cells. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990; 26:503-13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2147673

74. Fernandes PB, Ramer N, Rode RA et al. Bioassay for A-56268 (TE-031) and identification of its major metabolite, 14-hydroxy-6-O-methyl erythromycin. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1988; 7:73-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2967754

75. Sefton AM, Maskell JP, Yong FJ et al. Comparative in vitro activity of A-56268. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1988; 7:798-802. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2975218

76. Renaudin H, Bebéar C. Comparative in vitro activity of azithromycin, clarithromycin, erythromycin and lomefloxacin against Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum . Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990; 9:838-41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1964899

77. Rastogi N, Labrousse V. Extracellular and intracellular activities of clarithromycin used alone and in association with ethambutol and rifampin against Mycobacterium avium complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991; 35:462-70. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1828135 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC245033/

78. Powell M, Chen HY, Weinhardt B et al. In-vitro cidal activity of clarithromycin and its 14-hydroxy metabolite (A-62671) against Haemophilus influenzae . J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991; 27:694-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1832146

79. Barry AL, Fernandes PB, Jorgensen JH et al. Variability of clarithromycin and erythromycin susceptibility tests with Haemophilus influenzae in four different broth media and correlation with the standard disk diffusion test. J Clin Microbiol. 1988; 26:2415-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2976773 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC266903/

80. Logan MN, Ashby JP, Andrews JM et al. The in-vitro and disc susceptibility testing of clarithromycin and its 14-hydroxy metabolite. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991; 27:161-70. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1829073

81. Jorgensen JH, Maher LA, Howell AW. Activity of clarithromycin and its principal human metabolite against Haemophilus influenzae . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991; 35:1524-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1834012 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC245208/

82. Barry AL, Thornsberry C, Jones RN. In vitro activity of a new macrolide, A-56268, compared with that of roxithromycin, erythromycin, and clindamycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987; 31:343-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2952064 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC174723/

83. Fernandes PB, Hardy DJ. Comparative in vitro potencies of nine new macrolides. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1988; 14: 445-51.

84. Eliopoulos GM, Reiszner E, Ferraro MJ et al. Comparative in-vitro activity of A-56268 (TE-031), a new macrolide antibiotic. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988; 20:671-5.

85. Hodinka RL, Jack-Wait K, Gilligan PH. Comparative in vitro activity of A-56268 (TE-031), a new macrolide antibiotic. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1987; 6:103-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2952499

86. Floyd-Reising S, Hindler JA, Young LS. In vitro activity of A-56268 (TE-031), a new macrolide antibiotic, compared with that of erythromycin and other antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987; 31:640-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2955742 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC174797/

87. Berlin OG, Young LS, Floyd-Reising SA et al. Comparative in vitro activity of the new macrolide A-56268 against mycobacteria. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1987; 6:486-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2959472

88. Brown BA, Wallace RJ, Onyi GO et al. Activities of four macrolides, including clarithromycin, against Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonae, and M. chelonae-like organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992; 36(1):180-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1317144 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC189249/

89. Jones RN, Erwin ME, Barrett MS. In vitro activity of clarithromycin (TE-031, A-67268) and 14OH-clarithromycin alone and in combination against Legionella species. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990; 9:846-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2150817

90. Kohno S, Koga H, Yamaguchi K et al. A new macrolide, TE-031 (A-56268), in treatment of experimental Legionnaires’ disease. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989; 24:397-405. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2530201

91. Chirgwin K, Roblin PM, Hammerschlag MR. In vitro susceptibilities of Chlamydia pneumoniae (Chlamydia sp. strain TWAR). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989; 33:1634-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2817862 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC172720/

92. Benson C, Segreti J, Kessler H et al. Comparative in vitro activity of A-56268 (TE-031) against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria and Chlamydia trachomatis . Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1987; 6:173-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2954818

93. Felmingham D, Robbins MJ, Sanghrajka M et al. The in vitro activity of some 14-, 15- and 16-membered macrolides against Staphylococcus spp., Legionella spp., Mycoplasma spp. and Ureaplasma urealyticum . Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1991; 17:91-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1650694

94. Morimoto S, Nagate T, Sugita K et al. Chemical modification of erythromycins. III. In vitro and in vivo antibacterial activities of new semisynthetic 6-O-methylerythromycins A, TE-031 (clarithromycin) and TE-032. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 1990; 43(3):295-305. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2139023

95. Rolston K, Gooch G, Ho DH. In vitro activity of clarithromycin against Gram-positive bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989; 23:455-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2525120

96. Neu HC. New macrolide antibiotics: azithromycin and clarithromycin. Ann Intern Med. 1992; 116:517-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1310839

97. Hardy DJ, Guay DR, Jones RN. Clarithromycin, a unique macrolide: a pharmacokinetic, microbiological, and clinical overview. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992; 15:39-53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1530914

98. Davey PG. The pharmacokinetics of clarithromycin and its 14-OH metabolite. J Hosp Infect. 1991; 19(Suppl A): 29-37. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1684980

99. Wood MJ. The tolerance and toxicity of clarithromycin. J Hosp Infect. 1991; 19(Suppl A):39-46. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1684982

100. Ball P. The future role and importance of macrolides. J Hosp Infect. 1991; 19(Suppl A):47-59. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1684983

101. Anderson G. Clarithromycin in the treatment of community-acquired lower respiratory tract infections. J Hosp Infect. 1991; 19(Suppl A):21-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1684979

102. Chu SY, Park Y, Locke C et al. Drug-food interaction potential of clarithromycin, a new macrolide antimicrobial. J Clin Pharmacol. 1992; 32:32-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1531484

103. Adachi T, Morimoto S, Kondoh H et al. 14-Hydroxy -6-O-methylerythromycins A, active metabolites of 6-O-methylerythromycin A in human. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 1988; 41:966-75. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2971033

104. Preac-Mursic V, Wilske B, Schierz G et al. Comparative antimicrobial activity of the new macrolides against Borrelia burgdorferi . Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989; 8:651-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2550233

105. Kosek M, Alcantara C, Lima AAM et al. Cryptosporidiosis: an update. Lanc Infect Dis. 2001; 1:262-9.

106. Chen XM, Keithly JS, Paya CV et al. Cryptosporidiosis. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:1723-31. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12037153

107. Dajani A, Taubert K, Ferrieri P et al and the American Heart Association Committee on Rheumatic Fever et al. Treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis and prevention of rheumatic fever: a statement for health professionals. Pediatrics. 1995; 96:758-64. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7567345

108. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twelfth informational supplement. NCCLS document M100-S12. NCCLS: Wayne, PA; 2002 Jan.

109. Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002; 35:113-25. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12087516

110. Cooper RJ, Hoffman JR, Bartlett JG et al. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute pharyngitis in adults: background. Ann Intern Med. 2001; 134:509-17. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11255530

111. Holmberg SD, Moorman AC, Von Bargen JC et al. Possible effectiveness of clarithromycin and rifabutin for cryptosporidiosis chemoprophylaxis in HIV disease. HIV outpatient study (HOPS) investigators. JAMA. 1998; 279:384-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9459473

112. Agouron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Rescriptor (delavirdine mesylate) tablets prescribing information. La Jolla, CA; 2001 Jun 8.

113. Heffelfinger JD, Dowell SF, Jorgensen JH et al. Management of community-acquired pneumonia in the era of pneumococcal resistance. A report from the drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae therapeutic working group. Arch Intern Med. 2000; 160:1399-1408. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10826451

114. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: investigation of bioterrorism-related anthrax and interim guidelines for exposure management and antimicrobial therapy, October 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001; 50:909-19. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11699843

115. Dworkin MS, Hanson DL, Kaplan JE et al. Risk for preventable opportunistic infections in persons with AIDS after antiretroviral therapy increases CD4+ T lymphocyte counts above prophylaxis thresholds. J Infect Dis. 2000; 182:611-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10915098

116. Currier JS, Williams PL, Koletar SL et al. Discontinuation of Mycobacterium avium complex prophylaxis in patients with antiretroviral therapy-induced increases in CD4+ cell count. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000; 133:493-503. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11015162

117. El-Sadr WM, Burman WJ, Grant LB et al. Discontinuation of prophylaxis against Mycobacterium avium complex disease in HIV-infected patients who have a response to antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:1085-92. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10766581

118. Rossi M, Flepp M, Telenti A et al. Disseminated M. avium complex infection in the Swiss HIV cohort study: declining incidence, improved prognosis and discontinuation of maintenance therapy. Swiss Med Wkly. 2001; 131:471-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11641970

119. Soriano V, Dona C, Rodriguez-Rosado R et al. Discontinuation of secondary prophylaxis for opportunistic infections in HIV-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2000; 14:383-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10770540

121. Reviewers’ comments (personal observations).

122. Alder J, Mitten M, Hernandez L et al. Synergy between clarithromycin and sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of Pneumocystis carinii in rats. First International Conference on the Macrolides, Azalides and Streptogramins. Santa Fe, New Mexico, January 22-25, 1992. Abstract No. 179.

123. Hughes WT, Killmar JT. Synergistic anti-Pneumocystis carinii effects of clarithromycin and sulfamethoxazole. First International Conference on the Macrolides, Azalides and Streptogramins. Santa Fe, New Mexico, January 22-25, 1992. Abstract No. 180.

124. Cama VA, Marshall MM, Sterling CR. Synergy between clarithromycin and sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of Pneumocystis carinii in rats. First International Conference on the Macrolides, Azalides and Streptogramins. Santa Fe, New Mexico, January 22-25, 1992. Abstract No. 181.

125. Rehg JE. Anticryptosporidial activity of macrolides in immunosuppressed rats. First International Conference on the Macrolides, Azalides and Streptogramins, Santa Fe, New Mexico, January 22-25, 1992. Abstract No. 182.

126. Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL: Personal communication.

127. Suwa T, Yoshida H, Kohno Y et al. Metabolic fate of TE-031 (A-56268) (III). Absorption, distribution and excretion of 14C-TE-031 in rats, mice and dogs. Chemotherapy (Tokyo). 1988; 36(Suppl 3):223-6.

128. Pichotta P, Janousky S, Prokocimer P. Safety of clarithromycin in elderly patients. 17th International Congress of Chemotherapy, Berlin, Germany, June 1991. Abstract No. 1252.

129. Neu H, Craft JC. Clarithromycin vs cephalosporin therapy for the treatment of H. influenzae bronchitis. First International Conference on the Macrolides, Azalides and Streptogramins, Santa Fe, New Mexico, January 22-25, 1992. Abstract No. 237.

130. Dubois J, St. Pierre C, Prokocimer P. Treatment of community-acquired pneumonia: a comparison of clarithromycin and erythromycin. Proceedings of ICAAC Atlanta 1990. Abstract.

131. Futterman M, Drnec J. Safety and efficacy of clarithromycin compared with erythromycin in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. Proceedings of ICAAC Atlanta 1990. Abstract.

132. Prokocimer P, Siepman N. Treatment of community-acquired pneumonia: a comparison of clarithromycin and erythromycin. First International Conference on the Macrolides, Azalides and Streptogramins, Santa Fe, New Mexico, January 22-25, 1992. Abstract No. 244.

133. Nicotra MB, Northcutt VJ. Results of comparative trials of clarithromycin and erythromycin in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. 17th International Congress of Chemotherapy, Berlin, Germany, June 1991. Abstract.

134. Block S, Hedrick J, Hammerschlag MR et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae in pediatric community-acquired pneumonia: comparative efficacy and safety of clarithromycin vs.erythromycin ethylsuccinate. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995; 14:471-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7667050

135. Prokocimer P. An evaluation of clarithromycin and cefixime for lower respiratory tract infections. First International Conference on the Macrolides, Azalides and Streptogramins, Santa Fe, New Mexico, January 22-25, 1992. Abstract No. 243.

136. Gupta S, Siepman N. Comparative safety and efficacy of clarithromycin versus reference agents in the treatment of mild to moderate bacterial skin or skin structure infections. First International Conference on the Macrolides, Azalides and Streptogramins, Santa Fe, New Mexico, January 22-25, 1992. Abstract No. 254.

137. Millikan L. Safety and efficacy of clarithromycin compared to cefadroxil in the treatment of children with mild to moderate bacterial skin or skin structure infections. Proceedings of ICAAC Atlanta 1990. Abstract.

138. Carey WD, Yanofsky H. Safety and efficacy of clarithromycin compared to erythromycin in the treatment of bacterial skin or skin structure infections. 7th Mediterranean Congress of Chemotherapy, Barcelona, Spain, May 1990. Abstract.

139. Mikell OL. Treatment of bacterial skin or skin structure infections: a comparison of clarithromycin and cefadroxil. 7th Mediterranean Congress of Chemotherapy, Barcelona, Spain, May 1990. Abstract.

140. Northcutt VJ, Craft JC, Pichotta P. Safety and efficacy of clarithromycin compared to erythromycin in the treatment of bacterial skin or skin structure infections. Proceedings of ICAAC Atlanta 1990. Abstract.

141. Chan GP, Garcia-Ignacio BY, Chavez VE et al. Clinical trial of clarithromycin for lepromatous leprosy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994; 38:515-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8203847 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC284490/

142. Ji B, Jamet P, Perani EG et al. Clarithromycin, a promising component of new combined regimens for the treatment of multibacillary leprosy. First International Conference on the Macrolides, Azalides and Streptogramins, Santa Fe, New Mexico, January 22-25, 1992. Abstract No. 266.

143. Stein GE, Christensen S, Mummaw N. Comparative study of clarithromycin and penicillin V in the treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991; 10:949-53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1838978

144. St. Pierre C, Dubois J, Prokocimer P et al. An evaluation of clarithromycin and amoxicillin/clavulanate for the treatment of acute maxillary sinusitis. First International Conference on the Macrolides, Azalides and Streptogramins, Santa Fe, New Mexico, January 22-25, 1992. Abstract No. 229.

145. Tinel M, Descatoire V, Larrey D et al. Effects of clarithromycin on cytochrome P-450. Comparison with other macrolides. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989; 250:746-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2527301

147. Johnson M, Mattson L, Bopp B et al. The in vitro protein binding of 14-hydroxy clarithromycin in human plasma. Proceedings of ICAAC Chicago 1991. Abstract.

148. Niki Y, Nakajima M, Tsukiyama K et al. [Effect of TE-031 (A-56268), a new oral macrolide antibiotic, on serum theophylline concentration.] (Japanese; with English abstract.) Chemotherapy (Tokyo). 1988; 36(Suppl 3):515-20.

150. Marion Merrell Dow. Seldane (terfenadine) tablets prescribing information. Kansas City, MO; 1993 Jan.

151. Marion Merrell Dow, Kansas City, MO: Personal communication.

152. Marion Merrell Dow. Dear health care professional letter regarding appropriate use of Seldane. Kansas City, MO: 1992 Jul 7.

153. Mathews DR, McNutt B, Okerholm R et al. Torsades de pointes occurring in association with terfenadine use. JAMA. 1991; 266:2375-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1920744

154. Honig PK, Zamani K, Woosley RL et al. Erythromycin changes terfenadine pharmacokinetics & electrocardiographic pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992; 51:156.

155. Honig PK, Woosley RL, Zamani K et al. Changes in the pharmacokinetics and electrocardiographic pharmacodynamics of terfenadine with concomitant administration of erythromycin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992; 52:231-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1526078

156. Peck CC, Temple R, Collins JM. Understanding consequences of concurrent therapies. JAMA. 1993; 269:1550-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8445821

157. Antihistamines, nonsedating/macrolide antibiotics. In: Tatro DS, Olin BR, Hebel SK, eds. Drug interaction facts. St. Louis: JB Lippincott Co; 1996(July):110d.

158. Anon. Safety of terfenadine and astemizole. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1992; 34:9-10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1732711

159. Monahan BP, Ferguson CL, Killeary ES et al. Torsades de pointes occurring in association with terfenadine use. JAMA. 1990; 264:2788-90. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1977935

160. Cruzan S (US Food and Drug Administration). HHS News. Press release No. P92-22. 1992 Jul 7.

161. Cortese LM, Bjornson DC. Comment: the new macrolide antibiotics and terfenadine. Ann Pharmacother. 1992; 26:1019. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1504390

162. Nightingale SL. Warnings issued on nonsedating antihistamines terfenadine and astemizole. JAMA. 1992; 268:705. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1322467

163. Anon. New boxed warnings added for Seldane, Hismanal. FDA Med Bull. 1992; 22(Sep):2-3.

164. Marion Merrell Dow. Seldane-D (terfenadine and pseudoephedrine hydrochloride) extended-release tablets prescribing information. (dated 1993 May). In: Physicians’ desk reference. 50th ed. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Company Inc; 1996:1538-40.

166. Woosley RL, Chen Y, Freiman JP et al. Mechanism of the cardiotoxic actions of terfenadine. JAMA. 1993; 269:1532-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8445816

167. Anon. Labeling change to reflect drug interaction between terfenadine and ketoconazole. FDA Med Bull. 1991; 21(Jul):4-5.

168. Rolf CN. Dear doctor letter regarding important drug warning of Seldane. Cincinnati, OH: Marion Merrell Dow; 1990 Aug 6.

169. Cortese LM, Bjornson DC. Potential interaction between terfenadine and macrolide antibiotics. Clin Pharm. 1992; 11:675. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1511540

170. Price TA, Tuazon CU. Clarithromycin-induced thrombocytopenia. Clin Infect Dis. 1992; 15:563-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1387810

171. US Public Health Service Task Force on Prophylaxis and Therapy for Mycobacterium avium complex. Recommendations on prophylaxis and therapy for disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex for adults and adolescents infected with human immunodeficiency virus. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993; 42(No. RR-9):1-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8418395 https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr4209.pdf

172. de Lalla F, Maserati R, Scarpellini P et al. Clarithromycin-ciprofloxacin-amikacin for therapy of Mycobacterium avium-Mycobacterium intracellulare bacteremia in patients with AIDS. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992; 36:1567-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1387303 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC191622/

173. Dautzenberg B, Saint Marc T, Meyohas MC et al. Clarithromycin and other antimicrobial agents in the treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium avium infections in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1993; 153:368-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8427539