Mefloquine (Monograph)

Brand name: Lariam

Drug class: Antimalarials

VA class: AP101

Chemical name: (R*,S*)-(±)-α-2-Piperidinyl-2,8-bis(trifluoromethyl)-4-quinolinemethanol

Molecular formula: C17H16F6N2O

CAS number: 53230-10-7

Introduction

Antimalarial; 4-quinolinemethanol derivative; quinine analog.1 2 3 7 161

Uses for Mefloquine

Prevention of Malaria

Prevention (prophylaxis) of malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum (including chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum) or P. vivax;1 2 50 51 54 62 63 64 105 115 121 130 134 designated an orphan drug by FDA for prevention of P. falciparum malaria resistant to chloroquine or other antimalarials.56

Recommended by CDC and others as a drug of choice for prophylaxis in those traveling to areas where chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum has been reported;115 121 134 also can be used for prophylaxis in those traveling to areas where chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum malaria has not been reported.115 121 134

Risk of acquiring malaria varies substantially from traveler to traveler and from region to region (even within a single country) because of differences in intensity of malaria transmission within the various regions and season, itinerary, duration, and type of travel.115 121 Malaria transmission occurs in large areas of Africa, Central and South America, parts of the Caribbean, Asia (including South Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East), Eastern Europe, and the South Pacific.115 Mosquito avoidance measures must be used in conjunction with prophylaxis since no drug is 100% effective in preventing malaria.121

Choice of antimalarial for prophylaxis depends on traveler’s risk of acquiring malaria in area(s) visited, risk of exposure to drug-resistant P. falciparum, other medical conditions (e.g., pregnancy), cost, and potential adverse effects.115 121 134

Active only against asexual erythrocytic forms of Plasmodium (not exoerythrocytic stages) and cannot prevent delayed primary attacks or relapse of P. ovale or P. vivax malaria or provide a radical cure;1 115 134 terminal prophylaxis with 14-day regimen of primaquine may be indicated in addition to mefloquine prophylaxis if travelers were exposed in areas where P. ovale or P. vivax is endemic.1 115 134

Information on risk of malaria in specific countries and mosquito avoidance measures and recommendations regarding whether prevention of malaria indicated and choice of antimalarials for prevention are available from CDC at [Web] and [Web].115

Treatment of Uncomplicated Malaria

Treatment of uncomplicated malaria caused by mefloquine-susceptible P. falciparum (including chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum) or P. vivax;1 2 134 143 144 designated an orphan drug by FDA for this use.56

For treatment of uncomplicated malaria caused by chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum or treatment of uncomplicated malaria when plasmodial species not identified, CDC recommends fixed combination of atovaquone and proguanil (atovaquone/proguanil), fixed combination of artemether and lumefantrine (artemether/lumefantrine), or regimen of quinine in conjunction with doxycycline, tetracycline, or clindamycin.143 144

For treatment of uncomplicated malaria caused by chloroquine-susceptible P. falciparum, P. malariae, or P. knowlesi or treatment of uncomplicated malaria when plasmodial species not identified and infection was acquired in areas where chloroquine resistance has not been reported, CDC recommends chloroquine (or hydroxychloroquine).143 144 Alternatively, CDC states that any of the regimens recommended for treatment of uncomplicated chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum malaria may be used if preferred, more readily available, or more convenient.143 144

Although mefloquine is an option for treatment of uncomplicated malaria caused by susceptible Plasmodium,143 144 CDC recommends the drug be used only when other recommended treatment regimens cannot be used.143

For treatment of uncomplicated malaria caused by chloroquine-resistant P. vivax, CDC recommends regimen of quinine and doxycycline (or tetracycline) given in conjunction with primaquine, atovaquone/proguanil given in conjunction with primaquine, or mefloquine given in conjunction with primaquine.144 143 Because quinine, doxycycline (or tetracycline), atovaquone/proguanil, and mefloquine are active only against asexual erythrocytic forms of Plasmodium (not exoerythrocytic stages), 14-day regimen of primaquine indicated to prevent delayed primary attacks or relapse and provide a radical cure whenever any of these drugs used for treatment of P. vivax or P. ovale malaria.134 143

Pediatric patients with uncomplicated malaria generally can receive same treatment regimens recommended for adults using age- and weight-appropriate drugs and dosages.143 144 For treatment of uncomplicated chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum in children <8 years of age, atovaquone/proguanil or artemether/lumefantrine usually recommended; mefloquine can be considered if no other options available.144 For treatment of chloroquine-resistant P. vivax malaria in children <8 years of age, CDC recommends mefloquine given in conjunction with primaquine.143 144 Alternatively, if mefloquine not available or not tolerated and if potential benefits outweigh risks, atovaquone/proguanil or artemether/lumefantrine can be used for treatment of chloroquine-resistant P. vivax in this age group.143 144

A drug of choice for treatment of uncomplicated malaria caused by chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum or chloroquine-resistant P. vivax in pregnant women.143 (See Pregnancy under Cautions.)

Because of resistance, not recommended for treatment of malaria acquired in Southeast Asia.144

Assistance with diagnosis or treatment of malaria is available from CDC Malaria Hotline at 770-488-7788 or 855-856-4713 from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Eastern Standard Time or CDC Emergency Operation Center at 770-488-7100 after hours and on weekends and holidays.143 144

Mefloquine Dosage and Administration

General

-

A mefloquine medication guide and information wallet card are available from the manufacturer to help individuals understand the risks of malaria, risks and benefits of taking mefloquine to prevent malaria, and the rare but potentially serious adverse effects associated with the drug.1

-

As required by law, a copy of the mefloquine medication guide must be supplied to patients each time mefloquine is dispensed for prevention of malaria.1

Administration

Oral Administration

Administer orally with ample water (at least 8 oz [240 mL] of water for an adult).1

Do not administer on an empty stomach.1

If patient receiving mefloquine for treatment of malaria vomits within 30 minutes after receiving a dose, give a full dose as replacement; if vomiting occurs within 30–60 minutes after the dose, give 50% of the dose as replacement.1 128 129 If vomiting recurs, monitor patient closely and consider alternative malaria treatment if improvement not observed within reasonable period of time.1

For administration in children and others unable to swallow tablets, mefloquine tablets may be crushed and mixed with a small amount of liquid (e.g., water, milk, other beverage).1 129

When a dose <125 mg (<½ of a 250-mg tablet) indicated for pediatric patients, gelatin capsules containing the calculated pediatric dosage should be prepared extemporaneously by a pharmacist using a crushed tablet.115 134

Dosage

Available as mefloquine hydrochloride; dosage in the US usually expressed in terms of the salt.1 Each 250-mg tablet of mefloquine hydrochloride commercially available in the US is equivalent to 228 mg of mefloquine base.1 Other formulations (e.g., 275-mg mefloquine hydrochloride tablets containing 250 mg of the base) may be available in other countries.134 161

Dosage in children is based on body weight.1

Pediatric Patients

Prevention of P. falciparum or P. vivax Malaria

Oral

Infants and children weighing ≤45 kg: Approximately 5 mg/kg once weekly on same day each week, preferably after main meal.1 (See Table 1.) Only limited experience in those weighing <20 kg (especially those weighing <5 kg).1 121

Children weighing >45 kg: 250 mg once weekly on same day each week, preferably after main meal.1 115 121

|

Weight (kg) |

Dosage Once Weekly |

|---|---|

|

≤9 |

5 mg/kg (prepared extemporaneously) |

|

>9 up to 19 |

62.5 mg (¼ of a 250-mg tablet; prepared extemporaneously) |

|

>19 up to 30 |

125 mg (½ of a 250-mg tablet) |

|

>30 up to 45 |

187.5 mg (¾ of a 250-mg tablet) |

Initiate mefloquine prophylaxis 1–2 weeks prior to entering malarious area and continue during and for 4 weeks after leaving the area.1 105 115 121 134 CDC recommends initiating mefloquine prophylaxis ≥2 weeks before travel.115 If there are concerns about tolerance or drug interactions, it may be advisable to initiate mefloquine prophylaxis 3–4 weeks prior to travel in individuals receiving other drugs to ensure that the combination of drugs is well tolerated and to allow ample time to switch to another antimalarial if necessary.1 105 115 134

If exposure occurred in areas where P. ovale or P. vivax is endemic, terminal prophylaxis with a 14-day regimen of primaquine may be indicated;115 134 give during final 2 weeks of mefloquine prophylaxis or, if not feasible, give after mefloquine prophylaxis discontinued.115

Treatment of Uncomplicated P. falciparum or P. vivax Malaria

Oral

Children ≥6 months of age: Manufacturer recommends 20–25 mg/kg and states that dividing dosage into 2 doses given 6–8 hours apart may reduce incidence and severity of adverse effects.1 CDC and other experts recommend that children receive 2-dose regimen consisting of an initial dose of 15 mg/kg followed by 10 mg/kg 6–12 hours later (total dose of 25 mg/kg).134 144

If a response not attained within 48–72 hours, use an alternative antimalarial; do not use mefloquine for retreatment.1

For those with P. vivax malaria, a 14-day regimen of primaquine also indicated to provide a radical cure and prevent delayed attacks or relapse.134 143 144

Adults

Prevention of P. falciparum or P. vivax Malaria

Oral

250 mg once weekly on same day each week, preferably after main meal.1 115 121 134

Initiate mefloquine prophylaxis 1–2 weeks prior to entering malarious area and continue during and for 4 weeks after leaving the area.1 105 115 121 134 CDC recommends initiating mefloquine prophylaxis ≥2 weeks before travel.115 If there are concerns about tolerance or drug interactions, it may be advisable to initiate mefloquine prophylaxis 3–4 weeks prior to travel in individuals receiving other drugs to ensure that the combination of drugs is well tolerated and to allow ample time to switch to another antimalarial if required.1 115

If exposure occurred in areas where P. ovale or P. vivax is endemic, terminal prophylaxis with a 14-day regimen of primaquine may be indicated;115 134 give during final 2 weeks of mefloquine prophylaxis or, if not feasible, give after mefloquine prophylaxis discontinued.115

Treatment of Uncomplicated P. vivax or P. falciparum Malaria

Oral

A single dose of 1250 mg (five 250-mg tablets) recommended by manufacturer.1 CDC and others recommend a 2-dose regimen consisting of an initial 750-mg dose (three 250-mg tablets) followed by a 500-mg dose (two 250-mg tablets) given 6–12 hours later (total dose of 1250 mg).134 144

If a response not attained within 48–72 hours, use an alternative antimalarial; do not use mefloquine for retreatment.1

For those with P. vivax malaria, a 14-day regimen of primaquine also indicated to provide a radical cure and prevent delayed attacks or relapse.134 143 144

Prescribing Limits

Pediatric Patients

Malaria

Prevention of P. falciparum or P. vivax Malaria

OralMaximum 250 mg once weekly.105

Treatment of P. falciparum or P. vivax Malaria

OralSpecial Populations

Hepatic Impairment

No specific recommendations available regarding need for dosage adjustment in individuals with hepatic impairment.1 Increased mefloquine plasma concentrations may occur because of decreased elimination.1 (See Hepatic Impairment under Cautions.)

Renal Impairment

No specific recommendations available regarding need for dosage adjustment in individuals with renal impairment.1

When used for prevention of malaria, limited data indicate dosage adjustment not necessary in those undergoing hemodialysis.1 49

Cautions for Mefloquine

Contraindications

-

Hypersensitivity to mefloquine, structurally related drugs (e.g., quinine, quinidine), or any ingredient in the formulation.1

-

Malaria prevention in individuals with active depression, recent history of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, psychosis, schizophrenia, or other major psychiatric disorders.1 (See Neuropsychiatric Effects under Cautions.)

-

History of seizures.1 (See Nervous System Effects under Cautions.)

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Nervous System Effects

Dizziness,1 2 50 51 54 61 63 64 68 69 75 76 77 78 98 101 103 headache,1 2 61 62 63 64 75 77 103 and insomnia1 2 50 51 54 61 63 64 75 76 77 101 are the most frequently reported nervous system effects in patients receiving mefloquine. Abnormal dreams,1 50 51 61 64 70 altered consciousness,70 76 forgetfulness,1 motor and sensory neuropathy (including paresthesia, tremor, ataxia),1 seizures,1 18 62 64 74 78 84 85 88 113 vertigo,1 62 103 and tinnitus and hearing impairment1 also reported.

Patients with epilepsy or history of seizures may be at increased risk of seizure,1 although seizures have occurred in those without such a history.2 64 74 75 78 128 Do not use for prevention of malaria in epilepsy patients; use for treatment of malaria in such patients only if there are compelling medical reasons for such use.1

Some adverse nervous system effects (e.g., dizziness or vertigo, tinnitus and hearing impairment, loss of balance) may occur shortly after mefloquine initiation, can continue for months or years after drug discontinuance, and may be permanent in some cases.1

Discontinue mefloquine and substitute alternative antimalarial if neurologic effects (e.g., dizziness or vertigo, loss of balance) occur in a patient receiving mefloquine for malaria prevention.1

Neuropsychiatric Effects

Severe neuropsychiatric disorders have been reported occasionally with mefloquine,1 63 78 86 including agitation or restlessness, anxiety, depression, mood changes, panic attacks, forgetfulness, confusion, hallucinations, aggression, psychotic or paranoid reactions, and encephalopathy.1 In some patients, these symptoms have been reported to continue for months or years after mefloquine was discontinued.1

There have been rare cases of suicidal ideation and suicide in patients receiving mefloquine.1 74

Do not use mefloquine for prevention of malaria in any individual with active depression, recent history of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, psychosis, schizophrenia, or other major psychiatric disorders.1 Use mefloquine with caution in individuals with a previous history of depression.1

Some neuropsychiatric manifestations (e.g., acute anxiety, depression, restlessness, confusion) occurring in a patient receiving mefloquine prophylaxis suggest a risk for more serious psychiatric events or adverse neurologic effects.1

Neuropsychiatric effects can occur in adults or children and may be particularly difficult to identify in children.1 If used for prolonged periods (e.g., for malaria prevention), evaluate patient periodically for neuropsychiatric effects.1 Vigilance required to monitor for such manifestations, especially in nonverbal children.1

Discontinue mefloquine and substitute alternative antimalarial if neuropsychiatric manifestations (e.g., acute anxiety, depression, restlessness or confusion, suicidal ideation) occur in a patient receiving mefloquine for malaria prevention.1

Interactions

Concomitant or sequential use with some other antimalarials (e.g., chloroquine, quinine, quinidine, halofantrine [not commercially available in US]) or certain other drugs (e.g., ketoconazole) may increase risk of potentially fatal prolongation of QTc interval and/or may increase risk for seizures.1 135 (See Interactions.)

Sensitivity Reactions

Hypersensitivity Reactions

Serious cutaneous reactions, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome,1 2 93 99 erythema multiforme,1 2 and cutaneous vasculitis,97 reported rarely.1 2

General Precautions

Cardiac Effects

Mefloquine is a myocardial depressant, and mefloquine-induced changes in several cardiac parameters have been described.1 2 Bradycardia,1 2 76 94 extrasystoles,1 2 reversible sinus arrhythmia,2 94 100 first degree AV-block,1 and prolongation of QTc interval and abnormal T waves reported.1

Hypertension,1 hypotension,1 flushing,1 syncope,1 chest pain,1 tachycardia,1 palpitations,1 62 77 98 and irregular pulse1 reported. Cardiopulmonary arrest,1 pericarditis,2 cardiovascular collapse,2 and MI2 reported rarely.1 2

Weigh benefits of mefloquine against risks of adverse effects in patients with cardiac disease.1 Some experts state the drug should not be used in patients with cardiac conduction abnormalities.134

Ocular Effects

Visual disturbances reported infrequently in patients receiving mefloquine.1 50 63 64 77 103 Dose-related ocular lesions (retinal degeneration, retinal edema, lenticular opacity) reported in long-term animal studies.1

If used for prolonged periods (e.g., for malaria prevention), periodically perform ophthalmic examinations.1

Selection and Use of Antimalarials

Do not use for initial treatment of severe malaria.1 143 Life-threatening, serious, or overwhelming malaria requires aggressive treatment with a parenteral antimalarial regimen.1 143 144

Do not use for treatment of malaria in patients who received the drug for prevention of malaria.1

Because of increased incidence of adverse effects and high failure rate, do not use mefloquine for retreatment in patients who did not respond to or were previously treated with the drug.1 69 70

Concomitant or sequential use with some other antimalarials (e.g., chloroquine, quinine, quinidine, halofantrine [not commercially available in US]) may result in serious adverse effects.1 135 147 (See Interactions.)

Laboratory Monitoring

If used for prolonged periods (e.g., for malaria prevention), periodically evaluate liver function.1

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Category B.1

Manufacturer states use mefloquine during pregnancy only when clearly needed and advise women of childbearing potential to use effective contraceptive measures while receiving the drug and for up to 3 months after last dose.1

CDC and AAP recommend mefloquine as the drug of choice for prevention of malaria in women who are pregnant, or likely to become pregnant, if exposure to chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum unavoidable.105 115 CDC also states that mefloquine is a drug of choice for treatment of uncomplicated malaria caused by chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum or chloroquine-resistant P. vivax.143 144

Although reproduction studies in mice, rats, and rabbits have shown teratogenic effects at doses similar to those used for malaria treatment,1 published data on use of mefloquine for prevention or treatment of malaria during pregnancy have not shown an increased risk of teratogenic effects or adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to the background rate in the general population.1

Lactation

Distributed into milk.1 2 102 107 Use with caution in nursing women.1

Because amount of mefloquine consumed by a nursing infant likely to be small, some clinicians suggest that risk to nursing infants of maternal use of prophylactic dosages of mefloquine is low.2 102 107 115 128

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy not established for treatment of malaria in children <6 months of age.1

Only limited data available regarding use for prevention or treatment of malaria in children weighing <20 kg (especially those weighing <5 kg).1 121

CDC states use of mefloquine for prevention or chemoprophylaxis of malaria may be considered in infants and children of any age, depending on risk of exposure to drug-resistant Plasmodium.115

Use in children for treatment of acute uncomplicated malaria caused by P. falciparum is supported by evidence from adequate and well-controlled studies in adults and from published open-label and comparative studies in children <16 years of age.1 100 101 102

Children of any age can contract malaria, and indications for prophylaxis and treatment of malaria in children are the same as those for adults.22 100 101 102 105 113 128 129

Because of risks associated with malaria infection in children <6 weeks of age or weighing <5 kg, some experts recommend advising parents of such infants not to travel to countries with endemic malaria.105

Children ≤6 years of age being treated for malaria experience early vomiting (within 1 hour of drug administration) more frequently than individuals 7–50 years of age;18 68 70 76 early vomiting may be a possible cause of treatment failure in some children.1 If a replacement dose not tolerated (see Administration under Dosage and Administration), closely monitor child and consider alternative antimalarial treatment if child does not improve within a reasonable period of time.1

Geriatric Use

Response in patients ≥65 years of age does not appear to differ from that in younger adults.1

Because mefloquine associated with ECG abnormalities, consider the greater frequency of cardiac disease observed in the elderly and weigh benefits of mefloquine therapy in geriatric individuals against possibility of adverse cardiac effects.1

Hepatic Impairment

Mefloquine elimination may be prolonged and plasma concentrations increased in patients with hepatic impairment, resulting in increased risk of adverse effects.1

Common Adverse Effects

GI effects (nausea, vomiting, loose stools or diarrhea, abdominal pain); CNS effects (dizziness, vertigo); neuropsychiatric events (headache, somnolence, sleep disorders); rash; pruritus.1 2 50 51 61 63 76 113 138

Drug Interactions

Metabolized by CYP3A4;1 does not inhibit or induce CYP isoenzymes.1

Substrate for and inhibitor of P-glycoprotein.1

Drugs Affecting or Metabolized by Hepatic Microsomal Enzymes

Potential pharmacokinetic interaction with drugs that are CYP3A4 inhibitors (possible increased mefloquine concentrations and increased potential for adverse effects associated with the drug).1 Use concomitantly with caution.1

Potential pharmacokinetic interaction with drugs that are CYP3A4 inducers (possible decreased mefloquine concentrations and possible decreased efficacy of the antimalarial).1 Use concomitantly with caution.1

Pharmacokinetic interactions not expected if mefloquine used concomitantly with drugs that are substrates for CYP isoenzymes.1

Drugs Affecting P-glycoprotein Transport System

Potential pharmacokinetic interactions if used concomitantly with drugs that are substrates for or are known to modify expression of P-glycoprotein; clinical importance unknown.1

Drugs Affecting QT Interval

Possibility of prolongation of QT interval if used concomitantly with other drugs that alter cardiac conduction, including antiarrhythmic agents, β-adrenergic blocking agents, calcium-channel blocking agents, antihistamines, tricyclic antidepressants, and phenothiazines.1 Some experts state that mefloquine may be used concomitantly with β-adrenergic blocking agents in patients without an underlying arrhythmia.105 134

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Anticonvulsants (carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, valproic acid) |

Possible decreased anticonvulsant concentrations and reduced seizure control1 2 74 |

Mefloquine generally contraindicated in patients with history of seizures;1 if used in an individual receiving an anticonvulsant, monitor anticonvulsant concentrations and adjust dosage as necessary1 |

|

Antimalarial agents |

Artemether/lumefantrine: Decreased concentrations and AUC of lumefantrine possibly because of mefloquine-induced decrease in bile production;145 146 no effect on pharmacokinetics of artemether or mefloquine145 146 Chloroquine, quinine, or quinidine: Possibility of serious ECG abnormalities, including QTc interval prolongation, and increased risk of seizures1 147 Halofantrine (not commercially available in US): Use after mefloquine has resulted in potentially fatal prolongation of QTc interval1 112 135 |

Artemether/lumefantrine: If used shortly after mefloquine, administer artemether/lumefantrine dose with food and monitor for decreased efficacy145 Chloroquine, quinine, or quinidine: Do not use concomitantly with mefloquine;134 use sequentially with caution;134 do not administer mefloquine until ≥12 hours after last dose of any of these drugs;1 if initiating quinidine in a patient who received mefloquine within preceding 12 hours, do not use loading dose of quinidine144 Halofantrine: Do not use concomitantly with mefloquine or within 15 weeks after last mefloquine dose1 |

|

HIV protease inhibitors (PIs) |

Ritonavir: Decreased AUC of ritonavir; no effect on mefloquine pharmacokinetics151 155 Ritonavir-boosted PIs: Pharmacokinetic interaction unknown155 |

HIV PIs: Some experts recommend caution if mefloquine used in patients receiving PIs155 |

|

Ketoconazole |

Substantially increased mefloquine concentrations, AUC, and elimination half-life;1 increased risk of potentially fatal prolongation of QTc interval1 |

Do not use ketoconazole concomitantly with mefloquine or within 15 weeks after last mefloquine dose1 |

|

Rifampin |

Decreased concentrations, AUC, and elimination half-life of mefloquine1 150 |

Manufacturer of mefloquine states use concomitantly with caution;1 some experts recommend avoiding concomitant use if possible and considering use of rifabutin (instead of rifampin) or using an alternative antimalarial155 |

|

Typhoid Vaccine |

Possibility of interference with immune response to typhoid vaccine live oral since mefloquine has in vitro activity against Salmonella typhi108 109 110 |

Delay vaccination with typhoid vaccine live oral for 24 hours after mefloquine dose;105 108 complete typhoid vaccination ≥3 days before initiating mefloquine prophylaxis1 2 |

Mefloquine Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Mefloquine is a racemic mixture of 2 erythro enantiomers whose rates of release, absorption, transport, action, degradation, and elimination may differ.1 2 4 30 41 42 43 44

Slowly absorbed from GI tract; peak concentrations in blood or plasma attained within 6–24 hours and appear to be proportional to dose.2 30 31 35 36 37 38 39 40 45

Food

Limited evidence indicates that bioavailability greater when administered with food than when administered in fasting state.2 3 49

Special Populations

Some evidence that peak blood or plasma concentrations of mefloquine are substantially higher in Asians than in other ethnic groups.2 30 37 38 Reason for this ethnic variation not determined; may involve differences in volume of distribution secondary to the relatively lower body fat in Asians or differences in enterohepatic circulation of mefloquine in Asians.2 40

Distribution

Extent

Widely distributed into body tissues and fluids.1 2 30 31 37 38 39 45 46 107

Concentrates in erythrocytes to a greater extent than in plasma.1 2 7 8 30 31 33 41 44 122 123

Distributed into CNS.74 83 However, because GI absorption may be incomplete and erratic in patients with severe malaria, do not rely on oral mefloquine therapy for malaria involving the CNS.1 128

Distributed into milk in low concentrations.1 2 102 107

Plasma Protein Binding

98% bound to plasma proteins.1 2 3 30 31 33 44 45

Elimination

Metabolism

Metabolized in the liver, but metabolic fate not fully determined.1 2 3

Extensively metabolized by CYP isoenzyme system,1 2 3 probably by CYP3A4.1

Plasma concentrations of the principal metabolite, the 4-carboxylic acid derivative, exceed those of mefloquine.1 3 31 44

Elimination Route

Mefloquine and its metabolites are excreted in feces, with only small amounts (<13% combined) eliminated in urine.1 2 3 42 48

Undergoes biliary excretion and extensive enterohepatic circulation;30 some evidence suggests that enterohepatic circulation and fecal elimination may be increased in patients with malaria compared with those in healthy adults.30

Mefloquine and its 4-carboxylic acid metabolite not appreciably removed by hemodialysis.1 49

Half-life

Terminal elimination half-life shows considerable interindividual variation, ranging from 13–33 days (mean: 21 days) in healthy adults and about 10–15 days in patients with uncomplicated malaria.1 2 30 31 35 37 38 39 41 42 45 47

Faster elimination in patients with uncomplicated malaria relative to healthy individuals may result from decreased enterohepatic recirculation and increased fecal elimination.30

In Thai children with uncomplicated malaria, a terminal elimination half-life of 9.8–10.7 days was reported in those 6–24 months of age and 5–12 years of age.120 137

Special Populations

Mefloquine elimination may be prolonged in patients with hepatic impairment, resulting in higher plasma concentrations.1

Alterations in mefloquine pharmacokinetics have been documented in pregnant women (e.g., increased mefloquine clearance in late pregnancy);1 2 106 such changes not considered clinically relevant.1

Stability

Storage

Oral

Tablets

20–25°C.1 Protect from light.161

Actions and Spectrum

-

A blood schizonticidal agent1 2 11 active against asexual erythrocytic forms of most strains of Plasmodium falciparum, P. malariae, P. ovale, and P. vivax, including some chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum.2 11 113 161 Not active against mature gametocytes or against intrahepatic stages of plasmodial development.2 11

-

Also active in vitro against Entamoeba histolytica,13 Giardia lamblia,15 and against larval and adult stages of Brugia patei and B. malayi.14

-

Mefloquine-resistant Plasmodium reported in geographic areas where mefloquine has been used.2 3 7 18 19 20 21 22 113 114 115 In addition, P. falciparum strains with in vitro resistance to mefloquine identified in areas before introduction of the drug (i.e., intrinsic resistance).2 7 23 25 26

-

Incidence of mefloquine-resistant P. falciparum varies geographically; reported predominately in areas in Southeast Asia where multidrug-resistant malaria occurs.1 115 Mefloquine-resistant P. falciparum confirmed in areas bordering Thailand and Burma (Myanmar) or Thailand and Cambodia, western provinces of Cambodia, eastern states of Burma on border between Burma and China, along borders of Laos and Burma, adjacent parts of Thailand-Cambodia border, and southern Vietnam.18 115

-

Cross-resistance between mefloquine and chloroquine reported in P. falciparum and P. vivax in vitro.152 153 Cross-resistance between mefloquine and quinine also reported.1 Cross-resistance between mefloquine and halofantrine (an antimalarial not commercially available in US) documented in vitro in P. falciparum.2 24 135

Advice to Patients

-

Importance of reading the medication guide supplied with mefloquine.1 Advise patients to carry the information wallet card with them when they are taking mefloquine.1

-

For prevention of malaria, necessity of starting mefloquine prophylaxis 1–2 weeks before arriving in an area with malaria.1

-

Necessity of taking protective measures to reduce contact with mosquitoes (protective clothing, insect repellents, mosquito nets, remaining in air-conditioned or well-screened areas).1 113 115 121 134

-

Possibility of contracting malaria during travel, regardless of prophylactic regimen used.1 113 115 121 134

-

Importance of seeking medical attention as soon as possible if febrile illness develops during or after return from a malaria-endemic area and of informing clinician of possible malaria exposure, including instances when such illness was self-treated as malaria during travel.1 113 115 121 134

-

Advise patients that some people are unable to take mefloquine because of adverse effects and that it may be necessary to change medications if this occurs.1

-

Advise patients that dizziness or vertigo, loss of balance, tinnitus, and other central or peripheral nervous system effects have occurred in patients receiving mefloquine; such effects can persist for months or years after the drug is discontinued and may be permanent in some cases.1 If such symptoms occur, importance of avoiding activities requiring alertness and fine motor coordination (e.g., driving, piloting aircraft, operating machinery, deep-sea diving).1 Caution patients receiving mefloquine for malaria prevention to discontinue the drug and contact their clinician if neurologic effects (e.g., dizziness or vertigo, loss of balance) occur; an alternative antimalarial should be substituted.1

-

Advise patients that neuropsychiatric symptoms ranging from severe anxiety, paranoia, and depression to hallucinations and psychotic behavior have occurred in patients receiving mefloquine;1 some manifestations (e.g., acute anxiety, depression, restlessness, confusion) suggest a risk for more serious psychiatric events or adverse neurologic effects.1 Caution patients receiving mefloquine for malaria prevention to discontinue the drug and contact their clinician if neuropsychiatric manifestations or suicidal ideation occurs; an alternative antimalarial should be substituted.1

-

Importance of informing clinician of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs and dietary or herbal products, and any concomitant illnesses.1

-

Importance of women informing clinicians if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1 Advise women of childbearing potential to use effective contraceptive measures while receiving mefloquine and for up to 3 months after drug discontinuance.1

-

Importance of advising patients of other important precautionary information.1 (See Cautions.)

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

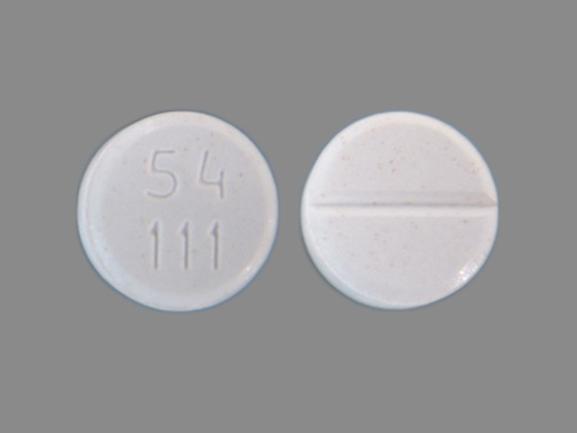

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Tablets |

250 mg* |

Mefloquine Hydrochloride Tablets (scored) |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions March 5, 2014. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

References

1. Teva Pharmaceuticals. Mefloquine hydrochloride tablets prescribing information. Sellersville, Pa; 2013 Jun.

2. Palmer KJ, Holliday SM, Brogden RN. Mefloquine: a review of its antimalarial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1993; 45:430-75. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7682911

3. Tracy JW, Webster LT Jr. Drugs used in the chemotherapy of protozoal infections: malaria. In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Molinoff PB et al, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1995:978-98..

4. Gimenez F, Pennie RA, Koren G et al. Stereoselective pharmacokinetics of mefloquine in healthy Caucasians after multiple doses. J Pharm Sci. 1994; 83:824-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9120814

5. Reber-Liske R. Note on the stability of mefloquine hydrochloride in aqueous solution. Bull World Health Organ. 1983; 61:525-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2536110/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6349842

6. Basco LK, Gillotin C, Gimenez F et al. In vitro activity of the enantiomers of mefloquine, halofantrine and enpiroline against Plasmodium falciparum. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1992; 33:517-20. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1381440/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1524966

7. Foley M, Tilley L. Quinoline antimalarials: mechanisms of action and resistance. Int J Parasitol. 1997; 27:231-40. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9088993

8. Desneves J, Thorn G, Berman A et al. Photoaffinity labelling of mefloquine-binding proteins in human serum, uninfected erythrocytes and Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996; 82:181-94. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8946384

9. Berman A, Shearing LN, Ng KF et al. Photoeffinity labeling of Plasmodium falciparum proteins involved in phospholipid transport. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994:67:235-43.

10. Geary TG, Divo AA, Jensen JB. Stage specific actions of antimalarial drugs on Plasmodium falciparum in culture. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989; 40:240-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2648881

11. Krogstad DJ. Plasmodium species (malaria). In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R eds. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1995:2415-26.

12. Basco LK, Gillotin C, Gimenez F et al. Absence of antimalarial activity or interaction with mefloquine enantiomers in vitro of the main human metabolite of mefloquine. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991; 85:208-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1887471

13. Osisanya JOS. Comparative in vitro activity of mefloquine, diloxanide furoate and other conventionally used amoebicides against entamoeba histolytica. E Afr Med J. 1986; 63:263-8.

14. Walter RD, Wittich RM, Kuhlow F. Filaricidal effect of mefloquine on adults and microfilariae of Brugia patei and Brugia malayi. Trop Med Parsitol. 1987; 38:55-6.

15. Crouch AA, Seow WK, Thong YH. Effect of twenty-three chemotherapeutic agents on the adherence and growth of Giardia lamblia in vitro. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1986; 80:893-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3603639

16. Karle JM, Karle IL. Crystal structure and molecular structure of mefloquine methylsulfonate monohydrate: implications for a malaria receptor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991; 35:2238-45. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC245366/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1803997

18. Nosten F, ter Kuile F, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T et al. Mefloquine-resistant falciparum malaria on the Thai-Burmese border. Lancet. 1991; 337:1140-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1674024

19. Sowunmi A, Oduola AMJ, Salako LA et al. The relationship between the response of Plasmodium falciparum malaria to mefloquine in African children and its sensitivity in vitro. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992; 86:368-71. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1440804

20. Lambros C, Notsch JD. Plasmodium falciparum: mefloquine resistance produced in vitro. Bull World Health Organ. 1984; 62:433-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2536315/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6380785

21. Oduola AMJ, Milhous WK, Weatherly NF et al. Plasmodium falciparum: induction of resistance to mefloquine in cloned strains by continuous drug exposure in vitro. Exp Parasitol. 1988; 67:354-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3056740

22. Nosten F, ter Kuile F, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T et al. Mefloquine pharmacokinetics and resistance in children with acute falciparum malaria. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1991; 31:556-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1368477/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1888626

23. White NJ. Mefloquine: in the prophylaxis and treatment of falciparum malaria. BMJ. 1994; 308:286-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2539249/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8124114

24. Gay F, Bustos DG, Diquet B et al. Cross-resistance between mefloquine and halofantrine. Lancet. 1990; 336:1262. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1978108

25. Brasseur P, Kauamouo J, Druilhe P. Mefloquine-resistant malaria induced by inappropriate quinine regimens? J Infect Dis. 1991; 164:625-6. Letter. (IDIS 288700)

26. Edrissian GH, Ghorbani M, Afshar A et al. In vitro response of Plasmodium falciparum to mefloquine in south-eastern Iran. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1987; 81:164-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3328332

27. Wilson CM, Serrano AE, Wasley A et al. Amplification of a gene related to mammalian mdr genes in drug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Science. 1989; 244:1184-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2658061

28. Wilson CM, Volkman SK, Thaithong S et al. Amplification of pfmdr 1 associated with mefloquine and halofantrine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum from Thailand. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993; 57:151-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8426608

29. Cowman AF, Galatis D, Thompson JK. Selection for mefloquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum is linked to amplification of the pfmdr1 gene and cross-resistance to halofantrine and quinine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994; 91:1143-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC521470/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8302844

30. Karbwang J, White NJ. Clinical pharmacokinetics of mefloquine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1990; 19:264-79. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2208897

31. Schwartz DE, Eckert G, Hartmann D et al. Single dose kinetics of mefloquine in man: plasma levels of the unchanged drug and of one of its metabolites. Chemotherapy. 1982; 28:70-84. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6976886

32. Parise ME (Division of Parasitic Diseases, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA). Personal communication; 2000 Sep 29.

33. Tajerzadeh H, Cutler DJ. Blood to plasma ratio of mefloquine: interpretation and pharmacokinetic implications. Biopharm Drug Disp. 1993; 14:87-91.

34. White NJ, Breman JG. Malaria and other diseases caused by red blood cell parasites. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, et al, eds. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. l4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998:1180-9.

35. Desjardins RE, Pamplin CL III, von Bredow J et al. Kinetics of a new antimalarial, mefloquine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1979; 26:372-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/466930

36. Karbwang J, Na Bangchang K, Bunnag D et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of mefloquine in Thai patients with acute falciparum malaria. Bull World Health Organ. 1991; 69:207-12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2393087/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1860148

37. Karbwang J, Back DJ, Bunnag D et al. A comparison of the pharmacokinetics of mefloquine in healthy Thai volunteers and in Thai patients with falciparum malaria. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1988; 35:677-80. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3069480

38. Karbwang J, Bunnag D, Breckenridge AM et al. The pharmacokinetics of mefloquine when given alone or in combination with sulphadoxine and pyrimethamine in Thai male and female subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1987; 32:173-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3495440

39. de Souza JM, Heizmann P, Schwartz DE. Single-dose kinetics of mefloquine in Brazilian male subjects. Bull World Health Organ. 1987; 65:353-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2491007/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3499250

40. Looareesuwan S, White NJ, Warrell DA et al. Studies of mefloquine bioavailability and kinetics using a stable isotope technique: a comparison of Thai patients with falciparum malaria and healthy caucasian volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987; 24:37-42. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1386277/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3304385

41. Martin C, Gimenez F, Bangchang KN et al. Whole blood concentrations of mefloquine enantiomers in healthy Thai volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1994; 47:85-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7988631

42. Hellgren U, Berggren-Palme I, Bergqvist Y et al. Enantioselective pharmacokinetics of mefloquine during long-term intake of the prophylactic dose. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997; 44:119-24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2042812/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9278194

43. Bourahla A, Martin C, Gimenez F et al. Stereoselective pharmacokinetics of mefloquine in young children. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996; 50:241-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8737767

44. Hellgren U, Jastrebova J, Jerling M et al. Comparison between concentrations of racemic mefloquine, its separate enantiomers and the carboxylic acid metabolite in whole blood serum and plasma. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996; 51:171-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8911884

45. Karbwang J, Na-Bangchang K. Clinical application of mefloquine pharmacokinetics in the treatment of P falciparum malaria. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1994; 8:491-502. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7721226

46. Boudreau EF, Fleckenstein L, Pang LW et al. Mefloquine kinetics in cured and recrudescent patients with acute falciparum malaria and in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1990; 48:399-409. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2225700

47. Mimica I, Fry W, Eckert G et al. Multiple-dose kinetic study of mefloquine in healthy male volunteers. Chemotherapy. 1983; 29:184-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6603336

48. Schwartz DE, Eckert G, Ekue JMK. Urinary excretion of mefloquine and some of its metabolites in African volunteers at steady state. Chemotherapy. 1987; 33:305-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3499298

49. Crevoisier CA, Joseph I, Fischer M et al. Influence of hemodialysis on plasma concentration-time profiles of mefloquine in two patients with end-stage renal disease: a prophylactic drug monitoring study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995; 39:1892-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC162850/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7486943

50. Lobel HO, Miani M, Eng T et al. Long-term malaria prophylaxis with weekly mefloquine. Lancet. 1993; 341:848-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8096560

51. Lobel HO, Bernard KW, Williams SL et al. Effectiveness and tolerance of long-term malaria prophylaxis with mefloquine: need for a better dosing regimen. JAMA. 1991; 265:361-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1984534

52. Tonnesen HH, Grislingaas AL. Photochemical stability of biologically active compounds. II. Photochemical decomposition of mefloquine in water. Int J Pharm. 1990; 60:157-62.

53. Karle JM, Olmeda R, Gerena L et al. Plasmodium falciparum: role of absolute stereochemistry in the antimalarial activity of synthetic amino alcohol antimalarial agents. Exp Parasitol. 1993; 76:345-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8513873

54. Wallace MR, Sharp TW, Smoak B et al. Malaria among United States troops in Somalia. Am J Med. 1996; 100:49-55. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8579087

55. Boudreau E, Schuster B, Sanchez J et al. Tolerability of prophylactic Lariam regimens. Trop Med Parasitol. 1993; 44:257-65. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8256107

56. Food and Drug Administration. List of orphan designations and approvals. From FDA web site. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/opdlisting/oopd/index.cfm

61. Wolfe MS. Protection of travelers. Clin Infect Dis. 1997; 25:177-84. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9332506

62. Wyler DJ. Malaria chemoprophylaxis for the traveler. N Engl J Med. 1993; 329:31-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8505942

63. Steffen R, Fuchs E, Schildknecht J et al. Mefloquine compared with other malaria chemoprophylactic regimens in tourists visiting East Africa. Lancet. 1993; 341:1299-303. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8098447

64. Hopperus Buma APCC, van Thiel PPAM, Lobel HO et al. Long-term malaria chemoprophylaxis with mefloquine in Dutch marines in Cambodia. J Infect Dis. 1996; 173:1506-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8648231

66. Day JH, Behrens RH. Delay in onset of malaria with mefloquine prophylaxis. Lancet. 1995; 345:398. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7845154

67. Dixon KE, Pitaktong U, Phintuyothin P. A clinical trial of mefloquine in the treatment of Plasmodium vivax malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1985; 34:435-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3890575

68. ter Kuile FO, Nosten F, Thieren M et al. High-dose mefloquine in the treatment of multidrug-resistant falciparum malaria. J Infect Dis. 1992; 166:1393-400. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1431257

69. Smithuis FM, van Woensel JBM, Nordlander E et al. Comparison of two mefloquine regimens for treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria on the northeastern Thai-Cambodian border. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993; 37:1977-81. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC188103/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8239616

70. White NJ. The treatment of malaria. N Engl J Med. 1996; 335:800-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8703186

71. Nosten F, Luxemburger C, ter Kuile FO et al. Treatment of multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria with 3-day artesunate-mefloquine combination. J Infect Dis. 1994; 170:971-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7930743

72. Looareesuwan S, Viravan C, Vanijanonta S et al. Randomised trial of artesunate and mefloquine alone and in sequence for acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Lancet. 1992; 339:821-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1347854

73. de Vries PJ, Dien TK. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutic potential of artemisinin and its derivatives in the treatment of malaria. Drugs. 1996; 52:818-36. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8957153

74. Bem JL, Kerr L, Stuerchler D. Mefloquine prophylaxis: an overview of spontaneous reports of severe psychiatric reactions and convulsions. J Trop Med Hyg. 1992; 95:167-79. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1597872

75. Phillips-Howard PA, ter Kuile FO. CNS adverse events associated with antimalarial agents: fact or fiction? Drug Saf. 1995; 12:370-83.

76. ter Kuile FO, Nosten F, Luxemburger C et al. Mefloquine treatment of acute falciparum malaria: a prospective study of non-serious adverse effects in 3673 patients. Bull World Health Organ. 1995; 73:631-42. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2486817/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8846489

77. Schlagenhauf P, Steffen R, Lobel H et al. Mefloquine tolerability during chemoprophylaxis: focus on adverse event assessments, stereochemistry and compliance. Trop Med Int Health. 1996; 1:485-94. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8765456

78. Barrett PJ, Emmins PD, Clarke PD et al. Comparison of adverse events associated with use of mefloquine and combination of chloroquine and proguanil as antimalarial prophylaxis: postal and telephone survey of travellers. BMJ. 1996; 313:525-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2351944/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8789977

79. Sowunmi A, Adio RA, Oduola AMJ et al. Acute psychosis after mefloquine: report of six cases. Trop Geograph Med. 1995; 47:179-80.

80. Caillon E, Schmitt L, Moron P. Acute depressive symptoms after mefloquine treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 1992; 149:712. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1575269

81. Björkman A. Acute psychosis following mefloquine prophylaxis. Lancet. 1989; II:865.

82. Stuiver PC, Ligthelm RJ, Goud TJLM. Acute psychosis after mefloquine. Lancet. 1989; II:282.

83. Rouveix B, Bricaire F, Michon C et al. Mefloquine and an acute brain syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1989; 110:577-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2784297

84. Pous E, Gascón J, Obach J et al. Mefloquine-induced grand mal seizure during malaria chemoprophylaxis in a non-epileptic subject. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995; 89:434. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7570889

85. Ruff TA, Sherwen SJ, Donnan GA. Seizure associated with mefloquine for malaria prophylaxis. Med J Aust. 1994; 161:453. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7935106

86. Hennequin C, Bourée P, Bazin N et al. Severe psychiatric side effects observed during prophylaxis and treatment with mefloquine. Arch Intern Med. 1994; 154:2360-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7944858

87. Piening RB, Young SA. Mefloquine-induced psychosis. Ann Emerg Med. 1996; 27:792-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8644976

88. Singh K, Shanks GD, Wilde H. Seizures after mefloquine. Ann Intern Med. 1991; 114:994. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2024874

89. Croft AMJ, World MJ. Neuropsychiatric reactions with mefloquine chemoprophylaxis. Lancet. 1996; 347:326. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8569381

90. Speich R, Haller A. Central anticholinergic syndrome with the antimalarial drug mefloquine. N Engl J Med. 1994; 331:57-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8202114

91. Olson PE, Kennedy CA, Morte PD. Paresthesias and mefloquine prophylaxis. Ann Intern Med. 1992; 117:1058-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1443980

92. Stracher AR, Stoeckle MY, Giordano MF. Aplastic anemia during malarial prophylaxis with mefloquine. Clin Infect Dis. 1994; 18:263-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8161647

93. Van den Enden E, Van Gompel A, Colebunders R et al. Mefloquine-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Lancet. 1991; 337:683. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1672030

94. Laothavorn P, Karbwang J, Na Bangchang K et al. Effect of mefloquine on electrocardiographic changes in uncomplicated falciparum malaria patients. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Pub Health. 1992; 23:51-4.

95. Shlim DR. Severe facial rash associated with mefloquine. JAMA. 1991; 266:2560. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1834867

96. Martin GJ, Malone JL, Ross EV. Exfoliative dermatitis during malarial prophylaxis with mefloquine. Clin Infect Dis. 1993; 16:341-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8443327

97. White AC Jr, Gard DA, Sessoms SL. Cutaneous vasculitis associated with mefloquine. Ann Intern Med. 1995; 123:894. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7486482

98. Richter J, Burbach G, Hellgren U et al. Aberrant atrioventricular conduction triggered by antimalarial prophylaxis with mefloquine. Lancet. 1997; 349:101-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8996427

99. McBride SR, Lawrence CM, Pape SA et al. Fatal toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with mefloquine antimalarial prophylaxis. Lancet. 1997; 349:101. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8996426

100. Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Sabchareon A, Chantavanich P et al. A phase-III clinical trial of mefloquine in children with chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria in Thailand. Bull World Health Organ. 1987; 65:223-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2490838/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3301042

101. Sowunmi A, Oduola AMJ. Open comparison of mefloquine, mefloquine/sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine and chloroquine in acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria in children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995; 89:303-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7660443

102. Marcy SM. Malaria prophylaxis in young children and pregnant women. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996; 15:101-2.

103. Nosten F, ter Kuile F, Maelankiri L et al. Mefloquine prophylaxis prevents malaria during pregnancy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Infect Dis. 1994; 169:595-603. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8158032

104. Na Bangchang K, Davis TME, Looareesuwan S et al. Mefloquine pharmacokinetics in pregnant women with acute falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994; 88:321-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7974678

105. American Academy of Pediatrics. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012.

106. Nosten F, Karbwang J, White NJ et al. Mefloquine antimalarial prophylaxis in pregnancy: dose finding and pharmacokinetic study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1990; 30:79-85. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1368278/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2390434

107. Edstein MD, Veenendaal JR, Hyslop R. Excretion of mefloquine in human breast milk. Chemotherapy. 1988; 34:165-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3262044

108. Centers for Disease Control Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP). Typhoid immunization: recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 1994; 43(RR-14):1-7. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr4314.pdf

109. Horowitz H, Carbonaro CA. Inhibition of the Salmonella typhi oral vaccine strain, Ty21a, by mefloquine and chloroquine. J Infect Dis. 1992; 166:1462-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1431270

110. Brachman PS, Metchock B, Kozarsky PE. Effects of antimalarial chemoprophylactic agents on the viability of the Ty21a typhoid vaccine strain. Clin Infect Dis. 1992; 15:1057-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1457647

111. Kollaritsch H, Que JU, Kunz C et al. Safety and immunogenicity of live oral cholera and typhoid vaccines administered alone or in combination with antimalarial drugs, oral polio vaccine, or yellow fever vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1997; 175:871-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9086143

112. Nosten F, ter Kuile FO, Luxemburger C et al. Cardiac effects of antimalarial treatment with halofantrine. Lancet. 1993; 341:1054-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8096959

113. Lobel HO, Kozareky PE. Update on prevention of malaria for travelers. JAMA. 1997; 278:1767-71. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9388154

114. Shanks GD. The rise and fall of mefloquine as an antimalarial drug in South East Asia. Mil Med. 1984; 159:275-81.

115. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC health information for international travel, 2014. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services. Updates may be available at CDC website. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/yellowbook-home-2014.htm

116. ter Kuile F, White NJ, Holloway P et al. Plasmodium falciparum: in vitro studies of the pharmacodynamic properties of drugs used for the treatment of severe malaria. Exp Parasitol. 1993; 76:85-95. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8467901

117. Davis TME, Dembo LG, Kaye-Eddie SA et al. Neurological, cardiovascular and metabolic effects of mefloquine in healthy volunteers: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1996; 42:415-21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2042694/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8904612

118. Chanthavanich P, Looareesuwan S, White NJ et al. Intragastric mefloquine is absorbed rapidly in patients with cerebral malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1985; 34:1028-36. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3879657

119. Price R, Robinson G, Brockman A et al. Assessment of pfmdr 1 gene copy number by tandem competitive polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997; 85:161-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9106190

120. Singhasivanon V, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Sabchareon A et al. Pharmacokinetic study of mefloquine in Thai children aged 5–12 years suffering from uncomplicated falciparum malaria treated with MSP or MSP plus primaquine. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1994; 19:27-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7957448

121. . Advice for travelers. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2012; 10:45-56. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22777212

122. Fitch CD, Chan RL, Chevli R. Chloroquine resistance in malaria: accessibility of drug receptors to mefloquine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979; 15:258-62. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC352643/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/371544

123. San George RC, Nagel RL, Fabry ME. On the mechanism for the red-cell accumulation of mefloquine, an antimalarial drug. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984; 803:174-81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6608378

124. Karbwang J, Looareesuwan S, Phillips RE et al. Plasma and whole blood mefloquine concentrations during treatment of chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria with the combination mefloquine-sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987; 23:477-81. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1386099/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3555581

125. Mai NTH, Day NPJ, Chuong LV et al. Post-malaria neurological syndrome. Lancet. 1996; 348:917-21. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8843810

126. Smoak BL, Writer JV, Keep LW et al. The effects of inadvertent exposure of mefloquine chemoprophylaxis on pregnancy outcomes and infants of US army servicewomen. J Infect Dis. 1997; 176:831-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9291347

127. Wongsrichanalai C, Nguyen TD, Trieu NT et al. In vitro susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum isolates in Vietnam to artemisinin derivatives and other antimalarials. Acta Tropica. 1997; 63:151-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9088428

128. Reviewers’ comments (personal observations).

129. Luxemburger C, Price RN, Nosten F et al. Mefloquine in infants and young children. Ann Trop Pediatr. 1996; 16:281-6.

130. Ohrt C, Richie TL, Widjaja H et al. Mefloquine compared with doxycycline for the prophylaxis of malaria in Indonesian soldiers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1997; 126:963-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9182474

131. Croft AMJ, Clayton TC, World MJ. Side effects of mefloquine prophylaxis for malaria: an independent randomized controlled trial. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997; 91:199-203. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9196769

132. Vuurman EFPM, Muntjewerff ND, Uiterwijk MMC et al. Effects of mefloquine alone and with alcohol on psychomotor and driving performance. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996; 50:475-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8858275

133. Steketee RW, Wirima JJ, Slutsker L et al. Malaria treatment and prevention in pregnancy: indications for use and adverse events associated with use of chloroquine or mefloquine. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996; 55:50-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8702037

134. Anon. Drugs for parasitic infections. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2010; 8:e1-16. http://www.medletter.com

135. SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals. Halfan (halofantrine hydrochloride) tablets prescribing information. Philadelphia, PA: 2001 Oct.

136. Nosten F, Vincenti M, Simpson J et al. The effects of mefloquine treatment in pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis. 1999; 28:808-15. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10825043

137. Singhasivanon V, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Sabcharoen A et al. Pharmacokinetics of mefloquine in children aged 6 to 24 months. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1992; 17:275-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1301357

138. Peragallo MS, Sabatinelli G, Sarnicola G. Compliance and tolerability of mefloquine and chloroquine plus proguanil for long-term malaria chemoprophylaxis in groups at particular risk (the military). Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999; 93:73-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10492796

139. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria deaths following inappropriate malaria chemoprophylaxis—United States, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001; 50:597-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11476528

140. Anon. Drug ruled out as cause of violence at Army base in N.C. Washington Post. 2002 Oct 31.

141. Anon. Ft. Bragg deaths tied to marital woes, stress: report says Army culture discourages military families from seeking help. Washington Post. 2002 Nov 8.

143. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC treatment guidelines: Treatment of malaria (guidelines for clinicians). 2013 Jul. From the CDC website. Accessed 2013 Sep 27. http://www.cdc.gov/malaria

144. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for treatment of malaria in the United States (based on drugs currently available for use in the United States–updated July 1, 2013). From the CDC website. Accessed 2013 Sep 27. http://www.cdc.gov/malaria

145. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Coartem (artemether/lumefantrine) tablets prescribing information. East Hanover, NJ; 2013 Apr.

146. Lefèvre G, Bindschedler M, Ezzet F et al. Pharmacokinetic interaction trial between co-artemether and mefloquine. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2000; 10:141-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10727880

147. AR Scientific, Inc. Qualaquin (quinine sulfate) capsules prescribing information. Philadelphia, PA; 2013 Apr.

148. Saha P, Guha SK, Das S et al. Comparative efficacies of artemisinin combination therapies in Plasmodium falciparum malaria and polymorphism of pfATPase6, pfcrt, pfdhfr, and pfdhps genes in tea gardens of Jalpaiguri District, India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012; 56:2511-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3346630/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22314538

149. Santelli AC, Ribeiro I, Daher A et al. Effect of artesunate-mefloquine fixed-dose combination in malaria transmission in Amazon basin communities. Malar J. 2012; 11:286. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3472241/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22905900

150. Ridtitid W, Wongnawa M, Mahatthanatrakul W et al. Effect of rifampin on plasma concentrations of mefloquine in healthy volunteers. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2000; 52:1265-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11092571

151. Khaliq Y, Gallicano K, Tisdale C et al. Pharmacokinetic interaction between mefloquine and ritonavir in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001; 51:591-600. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2014486/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11422019

152. Chehuan YF, Costa MR, Costa JS et al. In vitro chloroquine resistance for Plasmodium vivax isolates from the Western Brazilian Amazon. Malar J. 2013; 12:226. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3704965/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23819884

153. Zatra R, Lekana-douki JB, Lekoulou F et al. In vitro antimalarial susceptibility and molecular markers of drug resistance in Franceville, Gabon. BMC Infect Dis. 2012; 12:307. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3534593/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23153201

155. Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (May 7, 2013). Updates may be available at HHS AIDS Information (AIDSinfo) website. http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov

161. World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 2nd edition. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. Updates may be available at WHO website. http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241547925/en/index.html

Related/similar drugs

More about mefloquine

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (28)

- Drug images

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: antimalarial quinolines

- Breastfeeding

- En español