Warfarin (Monograph)

Brand name: Jantoven

Drug class: Coumarin Derivatives

Warning

-

Possible major bleeding, sometimes fatal. More likely to occur during initiation of therapy and with higher dosages, resulting in a higher INR.

-

Monitor INR regularly. Patients at high risk for bleeding may benefit from more frequent INR monitoring, careful dosage adjustment to achieve desired INR, and shorter duration of therapy.

-

Drugs, dietary changes, and other factors affect INR levels achieved with warfarin sodium therapy.

-

Instruct patients about preventative measures to minimize risk of bleeding and to immediately report signs and symptoms of bleeding to clinician.

Introduction

Anticoagulant; a coumarin derivative.

Uses for Warfarin

Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism

Treatment of acute deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) (i.e., venous thromboembolism [VTE]) in adults.

Initiate concomitantly with a parenteral anticoagulant (e.g., low molecular weight heparin [LMWH], heparin, fondaparinux). Overlap parenteral and oral anticoagulant therapy for ≥5 days and until a stable INR of ≥2 has been maintained for ≥24 hours, then discontinue parenteral anticoagulant.

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends a moderate intensity of anticoagulation (target INR 2.5, range 2–3) for most patients with VTE.

Appropriate duration of therapy determined by individual factors (e.g., location of thrombi, presence or absence of precipitating factors, presence of cancer, patient's risk of bleeding). For most cases of VTE, a minimum of 3 months of anticoagulant therapy is recommended. Long-term anticoagulation (>3 months) may be considered in selected patients (e.g., those with idiopathic [unprovoked] VTE who are at low risk of bleeding, cancer patients with VTE).

Warfarin remains an option for treatment of VTE; however, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs; e.g., dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban) are preferred in most cases by experts such as ACCP, American Society of Hematology (ASH), and the Anticoagulation Forum. DOACs have similar efficacy to warfarin, but reduced bleeding (particularly intracranial hemorrhage) and greater convenience for patients and healthcare providers.

In patients with cancer and established VTE, LMWH or oral factor Xa inhibitors are generally recommended over warfarin for long-term anticoagulation.

Used in select pediatric patients with DVT or PE† [off-label]. LMWHs or heparin generally recommended for both initial and ongoing treatment of VTE in children; however, warfarin may be indicated in some situations (e.g., recurrent idiopathic VTE).

Prophylaxis of Venous Thromboembolism

Prevention of VTE in adults undergoing major orthopedic surgery (hip- or knee-replacement surgery or hip-fracture surgery).

ACCP recommends routine thromboprophylaxis (with a pharmacologic and/or mechanical method) in all patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery (hip- or knee-replacement surgery, hip-fracture surgery). Continue thromboprophylaxis for at least 10–14 days, and possibly for up to 35 days after surgery.

Several antithrombotic agents (e.g., LMWHs, fondaparinux, DOACs, low-dose heparin, warfarin, aspirin) recommended by experts for pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery.

Although LMWHs and DOACs generally preferred, alternative agents (e.g., warfarin) may be considered. Drug selection and duration of therapy should be individualized based on type of surgery, patient risk factors for embolism and bleeding, as well as costs, patient compliance, preference, tolerance, and comorbidities; and other clinical factors such as renal function.

Used for primary thromboprophylaxis in children with ventricular assist devices† [off-label] or with an arteriovenous fistula undergoing hemodialysis† [off-label] and in children with certain medical conditions associated with a high risk of thrombosis (e.g., large or giant coronary aneurysms following Kawasaki disease† [off-label], primary pulmonary hypertension† [off-label])

Embolism Associated with Atrial Fibrillation

Prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation.

ACCP, American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), the American Stroke Association (ASA), and other experts recommend antithrombotic therapy in all patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (i.e., atrial fibrillation in the absence of rheumatic mitral stenosis, a prosthetic heart valve, or mitral valve repair) who are at increased risk of stroke, unless such therapy is contraindicated.

Current guidelines recommend use of the CHA2DS2-VASc risk stratification tool for assessing a patient’s risk of stroke and need for anticoagulant therapy.

In patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who are eligible for oral anticoagulant therapy, DOACs are recommended over warfarin based on improved safety and similar or improved efficacy.

Anticoagulant selection should be individualized based on the absolute and relative risks of stroke and bleeding; costs; patient compliance, preference, tolerance, and comorbidities; and other clinical factors such as renal function and degree of INR control if the patient has been taking warfarin.

Experts suggest managing antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial flutter in the same manner as in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Cardioversion of Atrial Fibrillation†

Prevention of embolization in patients undergoing pharmacologic or electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation.

ACCP and other experts recommend that patients with atrial fibrillation of unknown or ≥48 hours' duration who are to undergo elective cardioversion receive therapeutic anticoagulation (e.g., warfarin, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, rivaroxaban) for ≥3 weeks prior to cardioversion; alternatively, a transesophageal echocardiography (TEE)-guided approach may be used. After successful cardioversion, all patients should receive therapeutic anticoagulation for ≥4 weeks.

Experts suggest the same approach to thromboprophylaxis in patients undergoing cardioversion for atrial flutter as that used in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Embolism Associated with Valvular Heart Disease

Prevention of thromboembolic complications in patients with valvular heart disease, including those with mechanical and bioprosthetic heart valves.

Assess risk of thromboembolism versus risk of bleeding when determining choice of antithrombotic therapy.

Among the common types of valvular heart disease, rheumatic mitral valve disease is associated with greatest risk of systemic thromboembolism; risk is further increased in patients with concurrent atrial fibrillation, left atrial thrombus, or history of systemic embolism.

The 2020 AHA/ACC guideline for management of valvular heart disease states that patients with valvular heart disease and atrial fibrillation should be evaluated for risk of thromboembolic events and treated with oral anticoagulation if at high risk. Vitamin K antagonists are the anticoagulants of choice for patients with rheumatic mitral stenosis and mechanical heart valves.

All patients with mechanical heart valves require long-term warfarin therapy because of the high risk of thromboembolism. Risk is higher with mechanical than with bioprosthetic heart valves, higher with first-generation mechanical (e.g., caged ball, caged disk) valves than with newer mechanical (e.g., bileaflet, Medtronic Hall tilting disk) valves, higher with more than one prosthetic valve, and higher with prosthetic mitral than with aortic valves; risk also is higher in the first few days and months after valve insertion and increases in the presence of atrial fibrillation.

In patients with mechanical aortic valve replacement who have additional risk factors (e.g., older generation valve, atrial fibrillation, previous thromboembolism, hypercoagulable state, left ventricular systolic dysfunction), a target INR of 3 (range 2.5–3.5) is recommended; in the absence of these risk factors, a target INR of 2.5 (range 2–3) is recommended.

In patients with mechanical mitral valve replacement, a target INR of 3 (range 2.5–3.5) is recommended.

Due to increased risk of major bleeding, addition of aspirin 75–100 mg is no longer routinely recommended in patients with mechanical valve replacement; the decision to add aspirin should be based on thromboembolism risk, bleeding risk, and presence of an indication for antiplatelet therapy.

Warfarin is recommended during the initial 3–6 months following surgical bioprosthetic valve replacement, regardless of position (aortic or mitral). Following transcatheter aortic valve implantation, the decision to select antiplatelet therapy or warfarin during the first 3–6 months should be individualized. The target INR is 2.5 (range 2–3) following either valve replacement approach. Following the initial period of warfarin prophylaxis, patients may be switched to aspirin 75–100 mg provided they are in normal sinus rhythm and have no other indication for therapeutic anticoagulation (e.g., atrial fibrillation, previous thromboembolism, hypercoagulable state, left ventricular dysfunction).

Generally should not initiate antithrombotic therapy in patients with infective endocarditis involving a native valve because of the risk of serious (e.g., intracerebral) hemorrhage and lack of documented efficacy. In patients with a prosthetic valve who are already receiving warfarin, ACCP suggests temporary discontinuance of the drug if infective endocarditis develops.

ST-Segment-Elevation MI (STEMI)

Used for secondary prevention to reduce the risk of death, recurrent MI, and thromboembolic events such as stroke or systemic embolization after acute ST-segment-elevation MI (STEMI).

Manufacturer states that following an acute STEMI in high-risk patients (e.g., those with a large anterior STEMI, substantial heart failure, intracardiac thrombus visible on transthoracic echocardiography, atrial fibrillation, history of previous thromboembolic event), use of warfarin (target INR 2–3) in conjunction with low-dose aspirin (not exceeding 100 mg daily) for at least 3 months is recommended.

Antiplatelet therapy preferred over warfarin for secondary prevention and risk reduction in patients with atherosclerosis, including those with acute STEMI unless there is a separate indication for use (e.g., atrial fibrillation, prosthetic heart valve, left ventricular thrombus or high risk for such thrombi, or concomitant venous thromboembolic disease).

Due to the lack of data supporting routine anticoagulation in the current era of reperfusion, coronary stenting, and dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), experts state prophylactic anticoagulation to prevent left ventricular thrombus post-STEMI is not routinely recommended for all patients.

Therapeutic anticoagulation (e.g., with warfarin, DOACs) for the treatment of left ventricular thrombus after acute MI is appropriate.

Cerebral Embolism

Antiplatelet agents generally preferred over oral anticoagulation for secondary prevention of noncardioembolic stroke in patients with a history of ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA).

Oral anticoagulation with warfarin or DOAC (e.g., apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, edoxaban) is recommended for secondary prevention of cerebral embolism in patients with TIAs or ischemic stroke and concurrent atrial fibrillation, provided no contraindications exist.

Warfarin anticoagulation also is recommended for prevention of recurrent stroke in patients at high risk for recurring cerebral embolism from other cardiac sources (e.g., prosthetic mechanical heart valves, anterior MI and left ventricular thrombus).

American Heart Association Stroke Council recommends warfarin following initial therapy with heparin or LMWH in patients with acute cerebral venous sinus thrombosis†.

Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia

ACCP and ASH state that warfarin may be used as follow-up therapy after initial parenteral treatment with a nonheparin anticoagulant (e.g., argatroban, bivalirudin, fondaparinux) in patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). Overlap therapy with warfarin and the nonheparin anticoagulant for ≥5 days and until desired INR has been achieved.

Do not initiate warfarin in patients with HIT until substantial platelet recovery occurs (e.g., platelet count ≥150,000/mm3); in patients already receiving warfarin at the time of HIT diagnosis, experts recommend administration of vitamin K.

Thrombotic Antiphospholipid Syndrome†

The International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) recommends use of warfarin over DOACs in patients with high-risk antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), including those with triple-positive APS and patients non-adherent to warfarin or with recurrent thrombosis while on therapeutic intensity warfarin.

Warfarin Dosage and Administration

General

Pretreatment Screening

-

Obtain baseline INR.

-

Obtain baseline CBC.

-

Verify pregnancy status in females of reproductive potential.

-

Perform other relevant baseline laboratory tests as needed based upon the patient’s clinical condition (e.g., liver function tests [LFTs]).

-

Assess patient for active bleeding and bleeding risk.

-

Assess patient for comorbid conditions (e.g., heart failure, diarrhea) and drug-drug interactions (e.g., amiodarone, metronidazole) that may influence warfarin dose selection.

-

Pharmacogenomic testing for CYP2C9 and vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKORC)1 genotypes is available and recommended, but not required.

Patient Monitoring

-

Perform INR assessments regularly during therapy.

-

Perform an INR assessment daily after warfarin initiation until the INR stabilizes in the therapeutic range.

-

ACCP states that INR assessments usually are performed daily in hospitalized patients until the INR is in the therapeutic range for at least 2 consecutive days; in nonhospitalized patients, initial INR assessments may be reduced from daily to every few days until a stable response has been achieved.

-

The frequency of INR assessments should be based on clinical judgment and patient response, but generally are performed every 1–4 weeks. In patients with consistently stable INRs, ACCP has suggested an INR testing interval of up to 12 weeks.

-

Monitor for signs and symptoms of bleeding (e.g., bruising, gum or nose bleeding, blood in stool).

-

Monitor for signs and symptoms of thrombosis (e.g., leg swelling).

-

Monitor CBC regularly and other laboratory tests based upon the patient’s clinical condition.

-

Monitor comorbid conditions (e.g., heart failure, diarrhea) for clinical changes that may influence the patient’s INR response to warfarin (e.g., diarrhea, resolved or decompensated heart failure).

-

Monitor for drug-drug interactions and drug therapy that is added, discontinued, or taken irregularly, that may influence the patient’s INR response.

-

Perform additional INR assessments when differing warfarin preparations (e.g., proprietary versus nonproprietary [generic]) are interchanged.

Dispensing and Administration Precautions

-

Personnel who are pregnant should avoid exposure to crushed or broken tablets.

-

Procedures for proper handling and disposal of potentially hazardous drugs should be considered.

-

Per the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), warfarin is a high-alert medication that has a heightened risk of causing significant patient harm when used in error.

-

The 2023 American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication (PIM) Use in Older Adults includes warfarin (for the treatment of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation or venous thromboembolism [VTE]) on the list of PIMs that are best avoided by older adults in most circumstances or under specific situations, such as certain diseases, conditions, or care settings. The criteria are intended to apply to adults 65 years of age and older in all ambulatory, acute, and institutional settings of care, except hospice and end-of-life care settings. The Beers Criteria Expert Panel recommends that use of warfarin as initial therapy for the treatment of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation or VTE be avoided unless alternative options (i.e., direct oral anticoagulants [DOACs]) are contraindicated or there are substantial barriers to their use. For older adults who have been using warfarin long-term, it may be reasonable to continue such therapy, particularly in those with well-controlled INRs (i.e., >70% time in the therapeutic range) and no adverse effects.

Other General Considerations

-

In patients managed by anticoagulation clinics, compared with patients receiving usual monitoring by their primary care clinician, available data indicate that the proportion of time in the therapeutic INR range and patient satisfaction is increased, but clinical outcomes such as bleeding, thrombosis, and mortality are not significantly different.

-

Self-testing with or without self-monitoring may be an option for some patients. A Cochrane systematic review with meta-analysis reported no difference in bleeding or mortality, and reduced thromboembolic events, when patient self-testing or self-monitoring was compared to standard therapy; however, the risk of bias downgraded the quality of evidence.

-

Self-management of warfarin therapy is suggested by ACCP as an alternative to outpatient INR monitoring in patients who are motivated and can demonstrate competency in self-management strategies, including the use of self-testing equipment.

Administration

Oral Tablets

Administer orally without regard to food.

Administer as a single daily dose at the same time each day.

If a dose is missed, take the dose as soon as possible on the same day. A double dose should not be taken the next day to make up for the missed dose.

Dosage

Dosage expressed in terms of warfarin sodium.

Initial dosage varies widely among patients; individualize dosage based on factors such as age, race, body weight, sex, genotype, concomitant drugs, and the specific indication being treated.

Routine use of warfarin loading doses not recommended by manufacturer. Some evidence suggests that use of a 10-mg loading dose may reduce time to therapeutic INR and the ACCP suggests that in sufficiently healthy, nonhospitalized patients, an initial dosage of 10 mg daily for the first 2 days may be administered, with subsequent dosing based on INR determinations.

In patients whose CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genotypes are not known, the manufacturer states that usual initial dosage is 2–5 mg daily or the expected maintenance dose.

For patients with known CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genotypes, the manufacturer suggests that initial dosage may be determined by expected maintenance dosages observed in clinical studies of patients with various combinations of these gene variants. (See Table 1.)

Manufacturer suggests using these expected maintenance dosage ranges to estimate initial daily dosage in patients with known CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genotypes. Dosage ranges derived from multiple published clinical studies. VKORC1-1639G > A (rs9923231) variant is used in this table; other co-inherited VKORC1 variants also may be important determinants of warfarin sodium dosage.

|

CYP2C9 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

VKORC1 |

*1/*1 |

*1/*2 |

*1/*3 |

*2/*2 |

*2/*3 |

*3/*3 |

|

GG |

5–7 mg |

5–7 mg |

3–4 mg |

3–4 mg |

3–4 mg |

0.5–2 mg |

|

AG |

5–7 mg |

3–4 mg |

3–4 mg |

3–4 mg |

0.5–2 mg |

0.5–2 mg |

|

AA |

3–4 mg |

3–4 mg |

0.5–2 mg |

0.5–2 mg |

0.5–2 mg |

0.5–2 mg |

Adjust maintenance dosage based on INR; if a previously stable patient presents with a single subtherapeutic or supratherapeutic INR (≤0.5 above or below the therapeutic range), ACCP suggests that current dosage be continued and INR retested within 1–2 weeks. If an unexpected result that does not fit the patient’s clinical picture occurs, consider repeating the INR.

The 2017 update of the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for pharmacogenetics-guided warfarin dosing suggests pharmacogenetic algorithm-based warfarin dosing over the genetics-based dosing table (Table 1) found in the FDA-approved warfarin label.

The recommended algorithms (Gage or International Warfarin Pharmacogenetics Consortium [IWPC]) consider age, sex, race or self-identified ancestry, weight, height, smoking status, warfarin indication, target INR, interacting drugs (e.g., amiodarone, phenytoin) and genetic variables (e.g., CYP2C9, VKORC1 genotypes). CPIC recommends the Gage over IWPC algorithm because it can adjust for CYP4F2, CYP2C9*5 and *6, if those genotypes are known.

Pediatric Patients

Warfarin dosage in pediatric patients varies based on age; infants generally have the highest, and adolescents have the lowest dosage requirements. ACCP generally suggests a target INR range of 2–3 for most indications in children except in the setting of prosthetic cardiac valves where adherence to adult recommendations is suggested.

Adults

Treatment of DVT and PE

Oral

Adjust dosage to achieve and maintain target INR of 2.5 (range 2–3).

Patients with proximal DVT or PE provoked by surgery or other transient risk factor: ACCP states that 3 months of anticoagulation usually sufficient.

Consider continuing anticoagulant therapy beyond 3 months depending on the individual clinical situation (e.g., location of thrombi, presence or absence of precipitating factors, presence of cancer, patient's risk of bleeding).

Prevention of DVT and PE

Major Orthopedic Surgery

OralAdjust dosage to INR range of 2–3.

ACCP recommends continuing thromboprophylaxis for at least 10–14 days, and possibly for up to 35 days after surgery.

Embolism Associated with Atrial Fibrillation

Oral

Maintain target INR of 2.5 (range 2–3) long term.

Manage atrial flutter in a similar manner as atrial fibrillation.

Cardioversion of Atrial Fibrillation

Oral

Patients with atrial fibrillation lasting ≥48 hours or of unknown duration: Initiate warfarin ≥3 weeks prior to cardioversion (target INR 2–3) and continue after the procedure until normal sinus rhythm maintained for ≥4 weeks.

Manage atrial flutter in a similar manner as atrial fibrillation.

Embolism Associated with Valvular Heart Disease

Oral

Patients with rheumatic mitral valve disease and concurrent atrial fibrillation, left atrial thrombus, or a history of systemic embolism: Maintain target INR of 2.5 (range 2–3).

Thromboembolism Associated with Prosthetic Heart Valves

Prophylaxis

OralBase intensity of anticoagulation on type of valve prosthesis. In general, target INR of 2.5 (range 2–3) suggested in patients with a mechanical aortic valve; target INR of 3 (range 2.5–3.5) recommended in those with a mechanical mitral valve.

Patients with mechanical heart valves in any position: Long-term oral anticoagulation required. The addition of low-dose aspirin (e.g., 50–100 mg daily) is no longer routine; the decision to use aspirin should be based on thromboembolism risk, bleeding risk, and presence of an indication for antiplatelet therapy.

Patients with bioprosthetic mitral or aortic valves: 3–6 months of warfarin therapy suggested after valve insertion; after 3 months, may switch to aspirin therapy, provided patient is in normal sinus rhythm and has no other indication for therapeutic anticoagulation (e.g., atrial fibrillation, previous thromboembolism, hypercoagulable state, left ventricular dysfunction).

Following transcatheter aortic valve implantation, the decision to select dual antiplatelet therapy or warfarin during the first 3–6 months, if the patient has a low risk of bleeding, should be individualized.

STEMI

Secondary Prevention

OralPatients at high risk of systemic or pulmonary embolism (e.g., large anterior STEMI, a history of previous thromboembolism, intracardiac thrombus, atrial fibrillation, or substantial heart failure): Warfarin (INR 2–3) and aspirin therapy (≤100 mg daily) following acute STEMI is an option.

Cerebral Thromboembolism

Secondary Prevention

OralPatients with TIA or ischemic stroke and concurrent atrial fibrillation: Maintain target INR of 2.5 (range 2–3) long term, provided no contraindications to therapy exist.

Warfarin is recommended in patients at high risk for recurring cerebral embolism from other cardiac sources (e.g., prosthetic mechanical heart valves, anterior MI, and left ventricular thrombus).

Patients with acute cerebral venous sinus thrombosis†: Target INR is 2–3 and recommended duration of therapy is based on known or unknown provocation and the presence or absence of thrombophilia.

HIT†

Conversion to Warfarin Therapy†

OralInitiate warfarin only after substantial recovery from acute HIT has occurred (i.e., platelet counts ≥150,000/mm3).

Overlap therapy with a nonheparin anticoagulant for ≥5 days until desired INR is achieved.

Maintain target INR of 2.5 (range 2–3).

Pharmacogenomic Considerationg in Dosing

Variations in genes responsible for warfarin metabolism or pharmacodynamic response may affect dosage requirements.

Lower dosages may be required to avoid excessive anticoagulation (e.g., INR >3) and bleeding in patients with variations in CYP2C9 and VKORC1.

Genetic information does not replace regular INR monitoring and results of genetic testing should not delay initiation of warfarin therapy.

Additional information about pharmacogenetic testing can be found at the Genetic Testing Registry ([Web]).

Transferring from Parenteral Anticoagulants to Warfarin

When warfarin is indicated for follow-up therapy after initial therapy with a parenteral anticoagulant (e.g., heparin, LMWH, fondaparinux), overlap therapy until adequate warfarin response obtained as indicated by INR monitoring.

Manufacturers recommend that heparin and warfarin be used concurrently for ≥4–5 days until the desired INR has been achieved.

In adults with acute DVT or PE, ACCP and ASH recommend that heparin, LMWH, or fondaparinux be used concurrently with warfarin for ≥5 days and until INR is ≥2 for ≥24 hours.

In children with VTE† in whom long-term warfarin therapy is being considered, ACCP recommends that warfarin be initiated on the same day as heparin or LMWH; overlap such therapy for ≥5 days and until the INR is therapeutic.

When warfarin is used for follow-up therapy after a nonheparin anticoagulant (e.g., argatroban, bivalirudin, fondaparinux) in patients with HIT†, overlap therapy for ≥5 days until adequate warfarin response is obtained as indicated by INR. Initiate warfarin therapy only after substantial recovery from acute HIT has occurred (i.e., stable platelet counts ≥150,000/mm3 or platelet recovery >50% of baseline). Do not use a warfarin loading dose in HIT patients.

Conversion from argatroban to warfarin is more complex than with other nonheparin anticoagulants since combined therapy with argatroban and warfarin prolongs the INR beyond that produced by warfarin alone. Consult manufacturer's prescribing information for specific guidelines for conversion. Monitor INR daily during concurrent argatroban and warfarin therapy.

Transferring from Other Anticoagulants to Warfarin

The manufacturer suggests consulting the labeling of other anticoagulants for instructions on conversion to warfarin.

Managing Anticoagulation in Patients Requiring Invasive Procedures

Temporary interruption of warfarin therapy may be required in patients undergoing surgery or other invasive procedures to minimize risk of perioperative bleeding.

Assess risk of thromboembolism versus risk of perioperative bleeding to determine whether interruption of therapy is necessary. Temporary interruption of therapy usually required for major surgical or invasive procedures, but may not be necessary for minor procedures associated with a low bleeding risk (e.g., minor dental procedures, minor dermatologic procedures, cataract surgery).

If temporary interruption of warfarin necessary prior to surgery, discontinue at least 5 days prior to procedure. Elderly patients with comorbidities, patients with low dose warfarin requirements, and those with a higher target INR range are among those who may require >5 days of warfarin interruption prior to surgery.

Determine the INR immediately prior to any invasive procedure.

May resume warfarin therapy within 24 hours postoperatively, usually on the evening of the surgery or procedure, when adequate hemostasis is achieved. Resume at the patient’s established maintenance dosage; loading doses (e.g., double the established maintenance dose) are not recommended.

Heparin bridging is defined as administration of an LMWH or IV heparin during the period of warfarin interruption. ACCP recommends against heparin bridging in patients with mechanical heart valves, atrial fibrillation, or VTE who are not considered to be high-risk for thromboembolism when warfarin is interrupted for an elective surgery or procedure. ACCP states that heparin bridging is recommended for patients at the highest risk for thromboembolism (e.g., patients with older-generation [e.g., tilting-disc] mechanical heart valves, any mechanical mitral valve, thromboembolic event within the last 3 months, atrial fibrillation patients with a CHA2DS2VASc score ≥7 or CHADS2 score ≥5).

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

The manufacturer makes no specific dosage recommendations; monitor more frequently for bleeding.

Renal Impairment

The manufacturer makes no specific dosage recommendations; more frequent INR monitoring may be required.

Geriatric Use

In patients >60 years of age, consider lower initial and maintenance dosages. More frequent monitoring may be necessary.

Debilitated Patients

Consider lower initial and maintenance dosages.

Asian Patients

May require lower initial and maintenance dosages.

Black Patients

The CYP2C9 *5, *6, *8, and *11 alleles associated with reduced enzymatic activity and warfarin metabolism occur in 45–50% of patients with self-reported African ancestry.

The 2017 update of the CPIC guideline for pharmacogenetics-guided warfarin dosing suggests a 15–30% warfarin dosage reduction when CYP2C9 *5, *6, *8, and *11 variant alleles are detected, regardless of self-reported ancestry.

Cautions for Warfarin

Contraindications

-

Pregnancy, except in patients with mechanical heart valves.

-

Patients with hemorrhagic tendencies or blood dyscrasias.

-

Recent or contemplated surgery of the eye or CNS and in those undergoing traumatic surgery resulting in large open surfaces.

-

Bleeding tendencies associated with active ulceration or overt bleeding of the GI, respiratory, or genitourinary tract; CNS hemorrhage; aneurysms (cerebral, dissecting aorta); pericarditis and pericardial effusions; bacterial endocarditis.

-

Threatened abortion, eclampsia, and preeclampsia.

-

Unsupervised patients with conditions associated with a potential high level of non-compliance with therapy (e.g., dementia/senility).

-

Known hypersensitivity (e.g., anaphylaxis).

-

Spinal puncture and other diagnostic or therapeutic procedures associated with the potential for uncontrollable bleeding.

-

Major regional or lumbar block anesthesia.

-

Malignant hypertension.

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Bleeding Risk

Risk of serious, potentially fatal, bleeding. (See Boxed Warning.)

Promptly evaluate if any manifestations of blood loss occur during therapy.

More likely to occur during the initiation of therapy and with higher dosages, resulting in higher INRs.

Risk factors for bleeding include higher dosages, high intensity of anticoagulation (INR >4), age ≥65 years, highly variable INRs, history of GI bleeding, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, anemia, malignancy, trauma, renal or liver impairment, alcohol abuse, prior stroke, certain genetic factors, concomitant drugs that may increase INR response, and a long duration of warfarin therapy.

Bleeding may still occur when the INR is in the usual therapeutic range.

GI or urinary tract bleeding may warrant investigation of underlying malignancy or other correctable lesions.

In patients with major bleeding requiring urgent warfarin reversal, ACCP and the ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway suggest the use of 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate (INR-based dose [e.g., 25, 35 or 50 units/kg] or fixed dose [e.g., 1000 units, 1500 units]) rather than fresh frozen plasma (FFP); additional use of vitamin K (5–10 mg by slow IV infusion) recommended.

Other Warnings and Precautions

Tissue Necrosis

Tissue necrosis and/or gangrene of skin or other tissues reported rarely.

Appears early within 1–10 days after initiation of therapy principally at sites of fat tissue (e.g., abdomen, breasts, buttocks, hips, thighs); reported more frequently in women.

Increased risk in patients with hereditary, familial, or clinical deficiencies of protein C or its cofactor, protein S.

Careful clinical evaluation is required to determine whether necrosis is caused by underlying disease.

Discontinue warfarin if tissue necrosis occurs; suggested treatments include supportive care, surgical debridement, aggressive wound care, and topical bactericidal agents. Consider alternative anticoagulants.

Systemic Atheroemboli and Cholesterol Microemboli

May result from possible increased release of atheromatous plaque emboli; some cases have progressed to necrosis and death. May occur 3–10 weeks or later following initiation of warfarin therapy.

The most common visceral organs involved are the kidneys, followed by the pancreas, spleen, and liver. Signs and symptoms vary depending on the site of embolization.

A distinct syndrome resulting from microemboli to the feet is known as ”purple toes syndrome.”

If signs and symptoms are observed, discontinue warfarin and consider an alternative anticoagulant.

Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis or calcium uremic arteriolopathy in patients with and without end stage renal disease reported; may be serious and/or fatal.

Occurs after a prolonged duration of therapy compared to warfarin-induced necrosis, which occurs typically within the first 10 days.

Discontinue warfarin, treat calciphylaxis as appropriate, and consider alternative anticoagulants.

Acute Kidney Injury

May occur in patients with altered glomerular integrity or with a history of kidney disease, possibly in relation to episodes of excessive anticoagulation and hematuria.

Monitor patients with compromised renal function more frequently.

Limb Ischemia, Necrosis, and Gangrene in Patients with HIT and HITTS

Do not use warfarin as initial therapy for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) or HIT with thrombosis syndrome (HITTS).

Cases of limb ischemia, necrosis, and gangrene have occurred in patients with HIT and HITTS when warfarin was initiated or continued after heparin discontinuance.

Amputation of the involved area and/or death have occurred.

Delay warfarin initiation until thrombin generation is adequately controlled and thrombocytopenia has resolved (i.e., platelet counts ≥150,000/mm3 and stable).

Use in Pregnant Women with Mechanical Heart Valves

Possible teratogenicity, fetal or neonatal hemorrhage, and intrauterine death.

Warfarin is generally contraindicated during pregnancy, but in women with mechanical heart valves at high risk of thromboembolism, manufacturer states the potential benefits of using warfarin may outweigh fetal risks.

If used during pregnancy, or if the patient becomes pregnant while taking warfarin, apprise patient of the potential fetal hazard.

Other Clinical Settings with Increased Risks

Utilize clinical judgment after weighing risks versus benefits of warfarin in the following situations: moderate to severe hepatic or renal impairment, infectious diseases (e.g., patients receiving antibiotic therapy) or disturbances of intestinal flora (e.g., sprue), patients with indwelling catheters, moderate to severe hypertension, acquired or hereditary protein C or protein S deficiencies, polycythemia vera, diabetes mellitus, eye surgery, and vasculitis.

Although diabetes mellitus is listed, this should be interpreted with caution because diabetes is a prominent factor in stroke scoring tools (e.g., CHA2DS2VASc, ATRIA), but it is a less consistent risk factor for bleeding.

The manufacturer states cataract surgery in patients taking warfarin has resulted in minor complications of sharp needle and local anesthesia block but has not been associated with potentially sight-threatening operative hemorrhagic complications. The decision to discontinue or reduce the warfarin dosage prior to less invasive or less complex eye surgery should be based on the patient’s risk of thromboembolism.

Endogenous Factors Affecting INR

Endogenous factors associated with increased INR response include diarrhea, hepatic disorders, poor nutritional state, steatorrhea, and vitamin K deficiency. Other factors have been reported in the literature (e.g., decompensated heart failure, non-euthyroid hyperthyroidism).

Endogenous factors associated with decreased INR response include increased vitamin K intake or hereditary warfarin resistance. Other factors have been reported in the literature (e.g., alcoholism following chronic ingestion, non-euthyroid hypothyroidism).

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

May cause fetal harm.

Contraindicated during pregnancy, but in women with mechanical heart valves at high risk of thromboembolism, the manufacturer states the potential benefits of using warfarin may outweigh fetal risks.

Multiple strategies to reduce and balance the maternal (e.g., valve thrombosis, death) and fetal risks (e.g., fetal loss, teratogenicity) are based on factors such as daily warfarin dosage, ability to utilize heparin or LMWH, ability to conduct frequent laboratory monitoring, and the patient's values and priorities.

No single anticoagulation strategy is optimally safe for both the mother and the fetus; maternal and fetal risks can be reduced, but not eliminated.

Consult ACC/AHA guidelines for recommendations on the management of women with mechanical heart valves who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant.

Consult other guidance documents (e.g., American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], American Society of Hematology [ASH]) for management of other warfarin indications in the context of pregnancy.

Lactation

Not significantly distributed into human breast milk or detectable in plasma of nursing infants; prolonged PT/INRs reported in some infants, but substantial coagulation abnormalities not observed.

ACOG, ASH, American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), ACCP, and other experts consider warfarin therapy to be compatible with breast-feeding.

Neonates are particularly sensitive to the effects of warfarin as a result of vitamin K deficiency. Monitor infants receiving human milk for bruising and bleeding.

Females and Males of Reproductive Potential

Counsel females of reproductive potential on potential risks to fetus and use of effective contraception.

Such patients should use effective contraception during treatment and for at least 1 month after the final dose.

Pediatric Use

Lack of adequate, well-controlled studies to inform optimum dosing, safety, and efficacy in pediatric patients.

Use based on adult data and recommendations, as well as limited pediatric data from observational studies and patient registries.

Has been used in pediatric patients for prevention and treatment of thromboembolic events. More frequent determinations of INR are recommended in pediatric patients.

Variable bleeding rates observed; pediatric patients should avoid activities or sports that may result in traumatic injury.

Geriatric Use

Increased sensitivity and anticoagulant response.

Increasing age confers increasing bleeding outcomes.

Consider lower initial and maintenance doses for elderly and/or debilitated patients. Conduct more frequent monitoring.

Hepatic Impairment

Increased anticoagulant response due to decreased synthesis of coagulation factors and decreased metabolism of warfarin.

Conduct more frequent monitoring for bleeding.

Renal Impairment

Renal clearance considered a minor determinant of anticoagulant response.

No dosage adjustment necessary.

The manufacturer suggests increased INR monitoring.

Common Adverse Effects

Most common adverse effects: fatal and nonfatal hemorrhage from any tissue or organ.

Drug Interactions

Drug interactions can occur via pharmacodynamic interactions (e.g., impaired hemostasis; increased or decreased intestinal synthesis or absorption of vitamin K; altered distribution or metabolism of vitamin K; increased warfarin affinity for receptor sites; decreased synthesis and/or increased catabolism of functional blood coagulation factors II, VII, IX, and X; interference with platelet function or fibrinolysis; ulcerogenic effects) or pharmacokinetic interactions (e.g., increased or decreased rate of warfarin metabolism; increased or decreased protein binding). Such interactions may increase or decrease response to warfarin.

Drugs Affecting Hepatic Microsomal Enzymes

Potential pharmacokinetic interaction with inhibitors or inducers of CYP2C9, 1A2, or 3A4 (increased warfarin exposure with concomitant inhibitors, decreased warfarin exposure with concomitant inducers). (See Table 2.) Closely monitor INR in patients who initiate, discontinue, or change dosages of these concomitant drugs.

list of drugs is not all-inclusive

|

Enzyme |

Inhibitors* |

Inducers* |

|---|---|---|

|

CYP2C9 |

amiodarone |

aprepitant |

|

capecitabine |

bosentan |

|

|

co-trimoxazole |

carbamazepine |

|

|

etravirine |

phenobarbital |

|

|

fluconazole |

rifampin |

|

|

fluvastatin |

||

|

fluvoxamine |

||

|

metronidazole |

||

|

miconazole |

||

|

oxandrolone |

||

|

tigecycline |

||

|

voriconazole |

||

|

zafirlukast |

||

|

CYP1A2 |

acyclovir |

montelukast |

|

allopurinol |

moricizine |

|

|

caffeine |

omeprazole |

|

|

cimetidine |

phenobarbital |

|

|

ciprofloxacin |

phenytoin |

|

|

disulfiram |

cigarette smoking |

|

|

enoxacin |

||

|

famotidine |

||

|

fluvoxamine |

||

|

methoxsalen |

||

|

mexiletine |

||

|

oral contraceptives |

||

|

propafenone |

||

|

propranolol |

||

|

terbinafine |

||

|

thiabendazole |

||

|

ticlopidine |

||

|

verapamil |

||

|

zileuton |

||

|

CYP3A4 |

alprazolam |

armodafinil |

|

amiodarone |

amprenavir |

|

|

amlodipine |

aprepitant |

|

|

amprenavir |

bosentan |

|

|

aprepitant |

carbamazepine |

|

|

atorvastatin |

efavirenz |

|

|

atazanavir |

etravirine |

|

|

bicalutamide |

modafinil |

|

|

cilostazol |

nafcillin |

|

|

cimetidine |

phenytoin |

|

|

ciprofloxacin |

pioglitazone |

|

|

clarithromycin |

prednisone |

|

|

conivaptan |

rifampin |

|

|

cyclosporine |

rufinamide |

|

|

darunavir/ritonavir |

||

|

diltiazem |

||

|

erythromycin |

||

|

fluconazole |

||

|

fluoxetine |

||

|

fluvoxamine |

||

|

fosamprenavir |

||

|

imatinib |

||

|

indinavir |

||

|

isoniazid |

||

|

itraconazole |

||

|

ketoconazole |

||

|

lopinavir/ritonavir |

||

|

nefazodone |

||

|

nelfinavir |

||

|

nilotinib |

||

|

oral contraceptives |

||

|

posaconazole |

||

|

ranitidine |

||

|

ranolazine |

||

|

ritonavir |

||

|

saquinavir |

||

|

tipranavir |

||

|

voriconazole |

||

|

zileuton |

Protein-bound Drugs

Drugs may competitively or noncompetitively interfere with protein binding and unbound warfarin may increase temporarily due to concomitant plasma half-life and renal clearance changes.

Marginal change in INR is transient.

Drugs that Increase Risk of Bleeding

Possible increased risk of bleeding with concomitant use of antiplatelet agents, NSAIAs, SSRIs, and anticoagulants other than warfarin. (See Table 3.)

Monitor closely. While the manufacturers of warfarin suggest close monitoring in those receiving NSAIAs, including selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, and others recommend gastroprotective agents when the combination cannot be avoided, some experts (ACCP) suggest that such concomitant therapy be avoided.

list of drugs is not all-inclusive

|

Drug Class |

Specific Drugs |

|---|---|

|

Anticoagulants |

argatroban, dabigatran, bivalirudin, heparin, fondaparinux, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, rivaroxaban, enoxaparin |

|

Antiplatelet agents |

aspirin, cilostazol, clopidogrel, dipyridamole, prasugrel, ticlopidine, ticagrelor, vorapaxar |

|

NSAIAs |

celecoxib, diclofenac, diflunisal, fenoprofen, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketoprofen, ketorolac, mefenamic acid, naproxen, oxaprozin, piroxicam, sulindac |

|

Serotonin-reuptake inhibitors |

citalopram, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, milnacipran, paroxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine, vilazodone |

Antibiotics or Antifungal Agents

Potential alteration in INR with concomitant use of certain antibiotics or antifungal agents; however, studies have not shown consistent effects on plasma warfarin concentrations.

Monitor INR closely when initiating or discontinuing any antibiotic or antifungal agent in patients receiving warfarin.

Dietary or Herbal Supplements

Concomitant therapy with dietary or herbal (botanical) supplements may alter an individual’s response to warfarin therapy. (See Tables 4 and 5.) Limited information is available regarding the interaction potential of dietary and herbal products. Exercise caution and perform additional PT/INR determinations whenever these products are added or discontinued.

|

agrimony |

chamomile (German and Roman) |

parsley |

|

alfalfa |

clove |

passion flower |

|

aloe gel |

*cranberry |

pau d’arco |

|

Angelica sinensis (dong quai) |

dandelion |

policosanol |

|

aniseed |

fenugreek |

poplar |

|

arnica |

feverfew |

prickly ash (Northern) |

|

asa foetida |

garlic |

quassia |

|

aspen |

German sarsaparilla |

red clover |

|

black cohosh |

ginger |

senega |

|

black haw |

Ginkgo biloba |

sweet clover |

|

bladder wrack (Fucus) |

ginseng (Panax) |

sweet woodruff |

|

bogbean |

horse chestnut |

tamarind |

|

boldo |

horseradish |

tonka beans |

|

bromelains |

inositol nicotinate |

wild carrot |

|

buchu |

licorice |

wild lettuce |

|

capsicum |

meadowsweet |

willow |

|

cassia |

nettle |

wintergreen |

|

celery |

onion |

|

agrimony |

goldenseal |

St. John’s wort |

|

coenzyme Q10 (ubidecarenone) |

mistletoe |

yarrow |

|

ginseng (Panax) |

Possible interaction between warfarin and cranberry juice (i.e., increased effect and possible increased risk of bleeding). Available data do not appear to support a clinically important interaction between warfarin and moderate cranberry juice (240–480 mL) or cranberry extract (≤1,350 mg/day) consumption; monitor closely for changes in INR and manifestations of bleeding.

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Acetaminophen |

Potential for increased anticoagulant effects; however, conflicting data exist regarding clinical importance |

Monitoring of INR recommended following initiation of, and during sustained therapy with large (>1.5 g daily) acetaminophen doses |

|

Alcohol |

Moderate amounts (300–600 mL wine daily) did not alter warfarin plasma concentrations or hypoprothrombinemic effect in healthy young men; effects of moderate consumption (e.g., 1–2 drinks daily) in patients receiving long-term therapeutic anticoagulation not well studied Acute ingestion of alcohol may enhance warfarin hypoprothrombinemc effect; long-term alcohol use (e.g., chronic alcoholism) associated with reduced warfarin effect through increased metabolism Antiplatelet effect of alcohol may increase bleeding risk without effects on INR |

Some clinicians recommend avoidance of concomitant alcohol ingestion Other clinicians suggest limiting alcohol consumption to small amounts (e.g., 1–2 drinks occasionally) during warfarin therapy and recommend against chronic heavy consumption (e.g., >720 mL beer, >300 mL wine, >60 mL liquor daily) |

|

Antiplatelet agents |

Increased risk of bleeding |

ACCP suggests avoiding concomitant use unless benefit is known or is highly likely to exceed potential harm from bleeding |

|

Capecitabine |

Inhibits CYP2C9 isoenzyme and decreases warfarin metabolism Possible increased anticoagulant response, increased PT/INR, and/or potentially fatal bleeding episodes, especially in patients >60 years of age with cancer |

Use concomitantly with caution Frequent monitoring of PT/INR recommended to facilitate anticoagulant dosage adjustments |

|

Cholestyramine |

Potential for decreased warfarin absorption and decreased warfarin half-life Potential decreased vitamin K absorption |

If concurrent use of cholestyramine and warfarin cannot be avoided, administer warfarin 1 hour before or ≥4 to 6 hours after cholestyramine |

|

Lomitapide |

Increased exposure to warfarin and increased INR |

Manufacturer of lomitapide suggests monitoring INR regularly, particularly following adjustments in lomitapide dosage, and adjusting warfarin dosage as clinically indicated |

|

Miconazole (vaginal) |

Potential for increased PT/INR and/or bleeding |

Monitoring PT/INR and appropriate dosage adjustments recommended with concomitant intravaginal miconazole therapy |

|

NSAIAs |

Potential for platelet aggregation inhibition, GI bleeding and peptic ulceration and/or perforation, altered PT/INR |

Manufacturer recommends close monitoring; ACCP suggests avoiding concomitant use unless benefit is known or is highly likely to exceed potential harm from bleeding |

|

Oxandrolone |

Potential for increased warfarin half-life and AUC Potential increased PT/INR and bleeding; necessary warfarin dosage reduction may be as high as 80% |

When oxandrolone therapy is initiated, changed, or discontinued, close monitoring of PT/INR and clinical response recommended to facilitate warfarin dosage adjustments and reduce bleeding risk |

Warfarin Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Essentially completely absorbed after oral administration; peak plasma concentration usually attained within 4 hours.

Onset

Synthesis of vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors is affected soon after absorption (e.g., within 24 hours). Depletion of circulating functional coagulation factors must occur before therapeutic effects of the drug become apparent.

Duration

2–5 days after a single dose.

Distribution

Extent

The apparent volume of distribution is about 0.14 L/kg.

Crosses the placental barrier; however, the drug has not been detected in human breast milk.

Plasma Protein Binding

Approximately 99%.

Elimination

Metabolism

Almost entirely in the liver. Principally by CYP2C9; CYP2C19, 2C8, 2C18, 1A2, and 3A4 involved to a lesser degree.

Elimination Route

Excreted principally in urine as metabolites.

Half-life

Effective half-life averages 40 hours (range: 20–60 hours).

Special Populations

Slightly decreased clearance of R-warfarin in geriatric patients compared with that in younger individuals. However, similar pharmacokinetics of racemic warfarin and S-warfarin in geriatric and younger individuals.

Decreased metabolism in patients with hepatic dysfunction.

Stability

Storage

Oral

Tablets

20–25°C.

Protect from light.

Actions

-

A coumarin-derivative anticoagulant.

-

A racemic mixture of the 2 optical isomers of the drug.

-

An indirect-acting anticoagulant; interferes with the hepatic synthesis of vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors II, VII, IX, and X. Also inhibits the anticoagulant proteins C and S.

-

Interferes with the action of reduced vitamin K, which is necessary for the γ-carboxylation of several glutamic acid residues in the precursor proteins of these coagulation factors. Inhibits clotting factor synthesis by inhibiting the regeneration of reduced vitamin K from vitamin K epoxide via inhibition of vitamin K epoxide reductase.

-

Sequential depletion of circulating functional coagulation factor VII, protein C, factor IX, protein S, factor X, and finally factor II.

-

Vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors physiologically decreased in neonates compared with adults; thrombin generation after warfarin therapy delayed and reduced in children compared with adults.

-

Antithrombogenic effects generally occur only after functional coagulation factors IX and X are diminished (usually 5–10 days following initiation of therapy).

-

Does not alter catabolism of blood coagulation factors.

-

Inhibits thrombus formation when stasis is induced; may prevent extension of existing thrombi. No direct effect on established thrombi.

-

Prolongs PT/INR and aPTT.

-

Phytonadione (vitamin K1) reverses the anticoagulant effect.

Advice to Patients

-

Inform patients to strictly adhere to the prescribed dosage schedule and to not discontinue therapy without first consulting a healthcare provider.

-

Inform patients that if a dose is missed, it should be taken as soon as possible on the same day; resume the regular dosing schedule the following day. Do not double a dose to make up for a missed dose.

-

Inform patients that INR tests must be obtained based on their healthcare provider’s recommendations and regular visits are necessary. Instruct patients that their healthcare provider will decide what INR goal is appropriate and adjust the warfarin dosage based on the INR results.

-

Advise patients that if warfarin is discontinued, the anticoagulant effects may persist for 2–5 days.

-

Inform patients that they may bruise and/or bleed more easily and that a longer than normal time may be required to stop bleeding when taking warfarin. Instruct patients to tell their healthcare provider about any unusual bleeding (e.g., nose bleeds, bleeding gums, heavier than normal menstrual bleeding, unexpected vaginal bleeding, pink or brown urine, red or black stools, coughing up blood, vomiting blood or material that looks like coffee grounds) or bruising during therapy.

-

Advise patients to avoid any activity or sport that may result in traumatic injury and to tell their healthcare provider if they fall often as this may increase their risk for complications.

-

Advise patients to eat a normal, balanced diet to maintain a consistent intake of vitamin K. Avoid drastic changes in dietary habits, such as eating large amounts of leafy, green vegetables.

-

Advise patients to report any serious illness, such as severe diarrhea, infection, or fever to their healthcare provider.

-

Advise patients to inform all healthcare providers, including dentists, about their warfarin therapy including before scheduling any medical, surgical, dental, or other invasive procedure.

-

Advise patients to carry identification notifying others of their current warfarin therapy.

-

Advise patients to immediately contact their healthcare provider if they experience pain and discoloration of the skin (a purple bruise-like rash) that primarily occurs on areas of the body with high fat content, such as breasts, thighs, buttocks, hips, and abdomen.

-

Advise patients to immediately contact a healthcare provider if they experience any unusual symptoms or pain since warfarin may cause small cholesterol or atheroemboli. When this occurs in the feet, symptoms may include sudden cool, painful, purple discoloration of the toe(s) or forefoot.

-

Advise patients to immediately contact a healthcare provider if any of the following occur: pain, swelling, discomfort, headache, dizziness, weakness, and fall or injury, especially if they hit their head.

-

Advise women to inform their clinician if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed. Effective measures to avoid pregnancy should be used while taking warfarin and for 1 month after the last dose.

-

Advise patients to inform their clinician of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs and dietary and herbal supplements, as well as any concomitant illnesses. Instruct patients not to take or discontinue any other drug, including salicylates (e.g., aspirin and topical analgesics), other OTC drugs, and botanical (herbal) products except on advice of a healthcare provider.

-

Advise patients of other important precautionary information.

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer’s labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

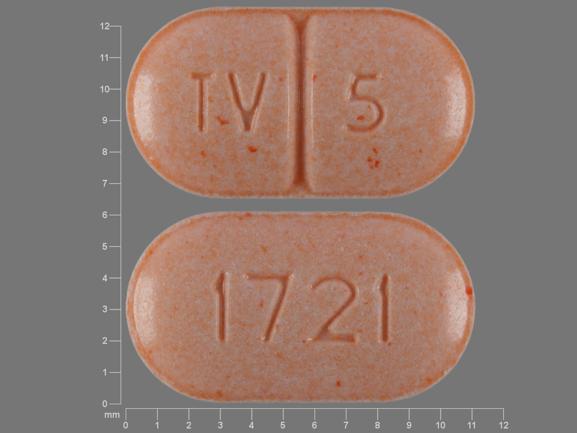

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Tablets |

1 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

||||

|

2 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

||

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

||||

|

2.5 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

||

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

||||

|

3 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

||

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

||||

|

4 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

||

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

||||

|

5 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

||

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

||||

|

6 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

||

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

||||

|

7.5 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

||

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

||||

|

10 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

||

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions June 10, 2025. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

Reload page with references included

Related/similar drugs

Frequently asked questions

- Does Green Tea interact with any drugs?

- What medications are known to cause hair loss?

- What is the antidote for warfarin?

- Is warfarin used as rat poison?

- Does Feverfew interact with any drugs?

- Why does warfarin cause purple toe syndrome?

- Does cranberry juice help prevent a UTI?

- Why are Warfarin tablets color-coded?

- Is your blood really thinner with warfarin?

More about warfarin

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (58)

- Drug images

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- Patient tips

- During pregnancy

- Support group

- Drug class: coumarins and indandiones

- Breastfeeding

- En español