Warfarin (Monograph)

Brand name: Jantoven

Drug class: Coumarin Derivatives

Warning

-

Possible major bleeding, sometimes fatal.330 More likely to occur during initiation of therapy and with higher dosages, resulting in a higher INR.330

-

Monitor INR regularly.330 Patients at high risk for bleeding may benefit from more frequent INR monitoring, careful dosage adjustment to achieve desired INR, and shorter duration of therapy.330

-

Drugs, dietary changes, and other factors affect INR levels achieved with warfarin sodium therapy.330

-

Instruct patients about preventative measures to minimize risk of bleeding and to immediately report signs and symptoms of bleeding to clinician.330

Introduction

Anticoagulant; a coumarin derivative.330

Uses for Warfarin

Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism

Treatment of acute deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) (i.e., venous thromboembolism [VTE]) in adults.330 1200

Initiate concomitantly with a parenteral anticoagulant (e.g., low molecular weight heparin [LMWH], heparin, fondaparinux).330 1200 Overlap parenteral and oral anticoagulant therapy for ≥5 days and until a stable INR of ≥2 has been maintained for ≥24 hours, then discontinue parenteral anticoagulant.1000 1200

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends a moderate intensity of anticoagulation (target INR 2.5, range 2–3) for most patients with VTE.1000 1200

Appropriate duration of therapy determined by individual factors (e.g., location of thrombi, presence or absence of precipitating factors, presence of cancer, patient's risk of bleeding).1106 1200 For most cases of VTE, a minimum of 3 months of anticoagulant therapy is recommended.330 1200 Long-term anticoagulation (>3 months) may be considered in selected patients (e.g., those with idiopathic [unprovoked] VTE who are at low risk of bleeding, cancer patients with VTE).1106 1200

Warfarin remains an option for treatment of VTE; however, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs; e.g., dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban) are preferred in most cases by experts such as ACCP, American Society of Hematology (ASH), and the Anticoagulation Forum.1006 1106 1200 DOACs have similar efficacy to warfarin, but reduced bleeding (particularly intracranial hemorrhage) and greater convenience for patients and healthcare providers.1006 1106 1200

In patients with cancer and established VTE, LMWH or oral factor Xa inhibitors are generally recommended over warfarin for long-term anticoagulation.1102 1103

Used in select pediatric patients with DVT or PE† [off-label].1013 1118 LMWHs or heparin generally recommended for both initial and ongoing treatment of VTE in children; however, warfarin may be indicated in some situations (e.g., recurrent idiopathic VTE).1013

Prophylaxis of Venous Thromboembolism

Prevention of VTE in adults undergoing major orthopedic surgery (hip- or knee-replacement surgery or hip-fracture surgery).330 1003

ACCP recommends routine thromboprophylaxis (with a pharmacologic and/or mechanical method) in all patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery (hip- or knee-replacement surgery, hip-fracture surgery).1003 Continue thromboprophylaxis for at least 10–14 days, and possibly for up to 35 days after surgery.1003

Several antithrombotic agents (e.g., LMWHs, fondaparinux, DOACs, low-dose heparin, warfarin, aspirin) recommended by experts for pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery.1003 1109

Although LMWHs and DOACs generally preferred, alternative agents (e.g., warfarin) may be considered.1003 1109 Drug selection and duration of therapy should be individualized based on type of surgery, patient risk factors for embolism and bleeding, as well as costs, patient compliance, preference, tolerance, and comorbidities; and other clinical factors such as renal function.1003 1108

Used for primary thromboprophylaxis in children with ventricular assist devices† [off-label] or with an arteriovenous fistula undergoing hemodialysis† [off-label] and in children with certain medical conditions associated with a high risk of thrombosis (e.g., large or giant coronary aneurysms following Kawasaki disease† [off-label], primary pulmonary hypertension† [off-label])1013 1165 1166 1167

Embolism Associated with Atrial Fibrillation

Prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation.223 278 279 369 456 459 990 999 1201 1017

ACCP, American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), the American Stroke Association (ASA), and other experts recommend antithrombotic therapy in all patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (i.e., atrial fibrillation in the absence of rheumatic mitral stenosis, a prosthetic heart valve, or mitral valve repair) who are at increased risk of stroke, unless such therapy is contraindicated.81 82 87 989 990 999 1201 1017

Current guidelines recommend use of the CHA2DS2-VASc risk stratification tool for assessing a patient’s risk of stroke and need for anticoagulant therapy.82 989 1201

In patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who are eligible for oral anticoagulant therapy, DOACs are recommended over warfarin based on improved safety and similar or improved efficacy.82 87 989 1201

Anticoagulant selection should be individualized based on the absolute and relative risks of stroke and bleeding; costs; patient compliance, preference, tolerance, and comorbidities; and other clinical factors such as renal function and degree of INR control if the patient has been taking warfarin.81 82 83 87 989 1201

Experts suggest managing antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial flutter in the same manner as in patients with atrial fibrillation.999 1201

Cardioversion of Atrial Fibrillation†

Prevention of embolization in patients undergoing pharmacologic or electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation.341 999 1201

ACCP and other experts recommend that patients with atrial fibrillation of unknown or ≥48 hours' duration who are to undergo elective cardioversion receive therapeutic anticoagulation (e.g., warfarin, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, rivaroxaban) for ≥3 weeks prior to cardioversion; alternatively, a transesophageal echocardiography (TEE)-guided approach may be used.999 1201 After successful cardioversion, all patients should receive therapeutic anticoagulation for ≥4 weeks.999 1201

Experts suggest the same approach to thromboprophylaxis in patients undergoing cardioversion for atrial flutter as that used in patients with atrial fibrillation.999 1201

Embolism Associated with Valvular Heart Disease

Prevention of thromboembolic complications in patients with valvular heart disease, including those with mechanical and bioprosthetic heart valves.330 341 342 343 370 1143 1202

Assess risk of thromboembolism versus risk of bleeding when determining choice of antithrombotic therapy.344 459 1202

Among the common types of valvular heart disease, rheumatic mitral valve disease is associated with greatest risk of systemic thromboembolism; risk is further increased in patients with concurrent atrial fibrillation, left atrial thrombus, or history of systemic embolism.1201 1202

The 2020 AHA/ACC guideline for management of valvular heart disease states that patients with valvular heart disease and atrial fibrillation should be evaluated for risk of thromboembolic events and treated with oral anticoagulation if at high risk.1143 Vitamin K antagonists are the anticoagulants of choice for patients with rheumatic mitral stenosis and mechanical heart valves.1143

All patients with mechanical heart valves require long-term warfarin therapy because of the high risk of thromboembolism.330 370 459 996 1143 1202 Risk is higher with mechanical than with bioprosthetic heart valves, higher with first-generation mechanical (e.g., caged ball, caged disk) valves than with newer mechanical (e.g., bileaflet, Medtronic Hall tilting disk) valves, higher with more than one prosthetic valve, and higher with prosthetic mitral than with aortic valves; risk also is higher in the first few days and months after valve insertion and increases in the presence of atrial fibrillation.341 342 343 370 1143 1202

In patients with mechanical aortic valve replacement who have additional risk factors (e.g., older generation valve, atrial fibrillation, previous thromboembolism, hypercoagulable state, left ventricular systolic dysfunction), a target INR of 3 (range 2.5–3.5) is recommended; in the absence of these risk factors, a target INR of 2.5 (range 2–3) is recommended.330 1143

In patients with mechanical mitral valve replacement, a target INR of 3 (range 2.5–3.5) is recommended.330 1143

Due to increased risk of major bleeding, addition of aspirin 75–100 mg is no longer routinely recommended in patients with mechanical valve replacement; the decision to add aspirin should be based on thromboembolism risk, bleeding risk, and presence of an indication for antiplatelet therapy.82 1143

Warfarin is recommended during the initial 3–6 months following surgical bioprosthetic valve replacement, regardless of position (aortic or mitral).82 330 1143 Following transcatheter aortic valve implantation, the decision to select antiplatelet therapy or warfarin during the first 3–6 months should be individualized.1143 The target INR is 2.5 (range 2–3) following either valve replacement approach.1143 Following the initial period of warfarin prophylaxis, patients may be switched to aspirin 75–100 mg provided they are in normal sinus rhythm and have no other indication for therapeutic anticoagulation (e.g., atrial fibrillation, previous thromboembolism, hypercoagulable state, left ventricular dysfunction).330 1143

Generally should not initiate antithrombotic therapy in patients with infective endocarditis involving a native valve because of the risk of serious (e.g., intracerebral) hemorrhage and lack of documented efficacy.1202 In patients with a prosthetic valve who are already receiving warfarin, ACCP suggests temporary discontinuance of the drug if infective endocarditis develops.1143 1202

ST-Segment-Elevation MI (STEMI)

Used for secondary prevention to reduce the risk of death, recurrent MI, and thromboembolic events such as stroke or systemic embolization after acute ST-segment-elevation MI (STEMI).330 527 992 1010

Manufacturer states that following an acute STEMI in high-risk patients (e.g., those with a large anterior STEMI, substantial heart failure, intracardiac thrombus visible on transthoracic echocardiography, atrial fibrillation, history of previous thromboembolic event), use of warfarin (target INR 2–3) in conjunction with low-dose aspirin (not exceeding 100 mg daily) for at least 3 months is recommended.330

Antiplatelet therapy preferred over warfarin for secondary prevention and risk reduction in patients with atherosclerosis, including those with acute STEMI unless there is a separate indication for use (e.g., atrial fibrillation, prosthetic heart valve, left ventricular thrombus or high risk for such thrombi, or concomitant venous thromboembolic disease).992 1010 1172

Due to the lack of data supporting routine anticoagulation in the current era of reperfusion, coronary stenting, and dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), experts state prophylactic anticoagulation to prevent left ventricular thrombus post-STEMI is not routinely recommended for all patients.1199

Therapeutic anticoagulation (e.g., with warfarin, DOACs) for the treatment of left ventricular thrombus after acute MI is appropriate.1199

Cerebral Embolism

Antiplatelet agents generally preferred over oral anticoagulation for secondary prevention of noncardioembolic stroke in patients with a history of ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA).82 1009

Oral anticoagulation with warfarin or DOAC (e.g., apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, edoxaban) is recommended for secondary prevention of cerebral embolism in patients with TIAs or ischemic stroke and concurrent atrial fibrillation, provided no contraindications exist.82 335 338 349 352 999 1009 1017

Warfarin anticoagulation also is recommended for prevention of recurrent stroke in patients at high risk for recurring cerebral embolism from other cardiac sources (e.g., prosthetic mechanical heart valves, anterior MI and left ventricular thrombus).82 1010 1199 1202

American Heart Association Stroke Council recommends warfarin following initial therapy with heparin or LMWH in patients with acute cerebral venous sinus thrombosis†.1175

Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia

ACCP and ASH state that warfarin may be used as follow-up therapy after initial parenteral treatment with a nonheparin anticoagulant (e.g., argatroban, bivalirudin, fondaparinux) in patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT).1168 1203 Overlap therapy with warfarin and the nonheparin anticoagulant for ≥5 days and until desired INR has been achieved.1203

Do not initiate warfarin in patients with HIT until substantial platelet recovery occurs (e.g., platelet count ≥150,000/mm3); in patients already receiving warfarin at the time of HIT diagnosis, experts recommend administration of vitamin K.1168 1203

Thrombotic Antiphospholipid Syndrome†

The International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) recommends use of warfarin over DOACs in patients with high-risk antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), including those with triple-positive APS and patients non-adherent to warfarin or with recurrent thrombosis while on therapeutic intensity warfarin.1163

Warfarin Dosage and Administration

General

Pretreatment Screening

-

Verify pregnancy status in females of reproductive potential.330

-

Perform other relevant baseline laboratory tests as needed based upon the patient’s clinical condition (e.g., liver function tests [LFTs]).330 1176 1177

-

Assess patient for active bleeding and bleeding risk.330 1176

-

Assess patient for comorbid conditions (e.g., heart failure, diarrhea) and drug-drug interactions (e.g., amiodarone, metronidazole) that may influence warfarin dose selection.330 1176 1177

-

Pharmacogenomic testing for CYP2C9 and vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKORC)1 genotypes is available and recommended, but not required.330 1178

Patient Monitoring

-

Perform an INR assessment daily after warfarin initiation until the INR stabilizes in the therapeutic range.330 1176 1177

-

ACCP states that INR assessments usually are performed daily in hospitalized patients until the INR is in the therapeutic range for at least 2 consecutive days; in nonhospitalized patients, initial INR assessments may be reduced from daily to every few days until a stable response has been achieved.1014 1176 1177

-

The frequency of INR assessments should be based on clinical judgment and patient response, but generally are performed every 1–4 weeks.330 In patients with consistently stable INRs, ACCP has suggested an INR testing interval of up to 12 weeks.1000 1176 1177

-

Monitor for signs and symptoms of bleeding (e.g., bruising, gum or nose bleeding, blood in stool).330 1176

-

Monitor for signs and symptoms of thrombosis (e.g., leg swelling).330 1176

-

Monitor CBC regularly and other laboratory tests based upon the patient’s clinical condition.330 1176

-

Monitor comorbid conditions (e.g., heart failure, diarrhea) for clinical changes that may influence the patient’s INR response to warfarin (e.g., diarrhea, resolved or decompensated heart failure).330 1176 1177

-

Monitor for drug-drug interactions and drug therapy that is added, discontinued, or taken irregularly, that may influence the patient’s INR response.330 1176 1177

-

Perform additional INR assessments when differing warfarin preparations (e.g., proprietary versus nonproprietary [generic]) are interchanged.330 1177

Dispensing and Administration Precautions

-

Personnel who are pregnant should avoid exposure to crushed or broken tablets. 330

-

Procedures for proper handling and disposal of potentially hazardous drugs should be considered.1206

-

Per the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), warfarin is a high-alert medication that has a heightened risk of causing significant patient harm when used in error.1205

-

The 2023 American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication (PIM) Use in Older Adults includes warfarin (for the treatment of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation or venous thromboembolism [VTE]) on the list of PIMs that are best avoided by older adults in most circumstances or under specific situations, such as certain diseases, conditions, or care settings.1001 The criteria are intended to apply to adults 65 years of age and older in all ambulatory, acute, and institutional settings of care, except hospice and end-of-life care settings.1001 The Beers Criteria Expert Panel recommends that use of warfarin as initial therapy for the treatment of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation or VTE be avoided unless alternative options (i.e., direct oral anticoagulants [DOACs]) are contraindicated or there are substantial barriers to their use.1001 For older adults who have been using warfarin long-term, it may be reasonable to continue such therapy, particularly in those with well-controlled INRs (i.e., >70% time in the therapeutic range) and no adverse effects.1001

Other General Considerations

-

In patients managed by anticoagulation clinics, compared with patients receiving usual monitoring by their primary care clinician, available data indicate that the proportion of time in the therapeutic INR range and patient satisfaction is increased, but clinical outcomes such as bleeding, thrombosis, and mortality are not significantly different.1180

-

Self-testing with or without self-monitoring may be an option for some patients.1179 A Cochrane systematic review with meta-analysis reported no difference in bleeding or mortality, and reduced thromboembolic events, when patient self-testing or self-monitoring was compared to standard therapy; however, the risk of bias downgraded the quality of evidence.1179

-

Self-management of warfarin therapy is suggested by ACCP as an alternative to outpatient INR monitoring in patients who are motivated and can demonstrate competency in self-management strategies, including the use of self-testing equipment.1000

Administration

Oral Tablets

Administer orally without regard to food.330

Administer as a single daily dose at the same time each day.330

If a dose is missed, take the dose as soon as possible on the same day.330 A double dose should not be taken the next day to make up for the missed dose.330

Dosage

Dosage expressed in terms of warfarin sodium.330

Initial dosage varies widely among patients; individualize dosage based on factors such as age, race, body weight, sex, genotype, concomitant drugs, and the specific indication being treated.330 1176 1177

Routine use of warfarin loading doses not recommended by manufacturer.330 Some evidence suggests that use of a 10-mg loading dose may reduce time to therapeutic INR and the ACCP suggests that in sufficiently healthy, nonhospitalized patients, an initial dosage of 10 mg daily for the first 2 days may be administered, with subsequent dosing based on INR determinations.1000

In patients whose CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genotypes are not known, the manufacturer states that usual initial dosage is 2–5 mg daily or the expected maintenance dose.330

For patients with known CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genotypes, the manufacturer suggests that initial dosage may be determined by expected maintenance dosages observed in clinical studies of patients with various combinations of these gene variants.330 (See Table 1.)

Manufacturer suggests using these expected maintenance dosage ranges to estimate initial daily dosage in patients with known CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genotypes.330 Dosage ranges derived from multiple published clinical studies.330 VKORC1-1639G > A (rs9923231) variant is used in this table; other co-inherited VKORC1 variants also may be important determinants of warfarin sodium dosage.330

|

CYP2C9 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

VKORC1 |

*1/*1 |

*1/*2 |

*1/*3 |

*2/*2 |

*2/*3 |

*3/*3 |

|

GG |

5–7 mg |

5–7 mg |

3–4 mg |

3–4 mg |

3–4 mg |

0.5–2 mg |

|

AG |

5–7 mg |

3–4 mg |

3–4 mg |

3–4 mg |

0.5–2 mg |

0.5–2 mg |

|

AA |

3–4 mg |

3–4 mg |

0.5–2 mg |

0.5–2 mg |

0.5–2 mg |

0.5–2 mg |

Adjust maintenance dosage based on INR; if a previously stable patient presents with a single subtherapeutic or supratherapeutic INR (≤0.5 above or below the therapeutic range), ACCP suggests that current dosage be continued and INR retested within 1–2 weeks.1000 1176 1177 If an unexpected result that does not fit the patient’s clinical picture occurs, consider repeating the INR.1176 1177

The 2017 update of the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for pharmacogenetics-guided warfarin dosing suggests pharmacogenetic algorithm-based warfarin dosing over the genetics-based dosing table (Table 1) found in the FDA-approved warfarin label.330 1178

The recommended algorithms (Gage or International Warfarin Pharmacogenetics Consortium [IWPC]) consider age, sex, race or self-identified ancestry, weight, height, smoking status, warfarin indication, target INR, interacting drugs (e.g., amiodarone, phenytoin) and genetic variables (e.g., CYP2C9, VKORC1 genotypes).1178 CPIC recommends the Gage over IWPC algorithm because it can adjust for CYP4F2, CYP2C9*5 and *6, if those genotypes are known.1178

Pediatric Patients

Warfarin dosage in pediatric patients varies based on age; infants generally have the highest, and adolescents have the lowest dosage requirements.330 ACCP generally suggests a target INR range of 2–3 for most indications in children except in the setting of prosthetic cardiac valves where adherence to adult recommendations is suggested.1013 1143

Adults

Treatment of DVT and PE

Oral

Adjust dosage to achieve and maintain target INR of 2.5 (range 2–3).330 1200

Patients with proximal DVT or PE provoked by surgery or other transient risk factor: ACCP states that 3 months of anticoagulation usually sufficient.330 1106 1200

Consider continuing anticoagulant therapy beyond 3 months depending on the individual clinical situation (e.g., location of thrombi, presence or absence of precipitating factors, presence of cancer, patient's risk of bleeding).330 1106 1200

Prevention of DVT and PE

Major Orthopedic Surgery

OralAdjust dosage to INR range of 2–3.1003

ACCP recommends continuing thromboprophylaxis for at least 10–14 days, and possibly for up to 35 days after surgery.1003

Embolism Associated with Atrial Fibrillation

Oral

Maintain target INR of 2.5 (range 2–3) long term.330 989 1201

Manage atrial flutter in a similar manner as atrial fibrillation.989 1201

Cardioversion of Atrial Fibrillation

Oral

Patients with atrial fibrillation lasting ≥48 hours or of unknown duration: Initiate warfarin ≥3 weeks prior to cardioversion (target INR 2–3) and continue after the procedure until normal sinus rhythm maintained for ≥4 weeks.999 1201

Manage atrial flutter in a similar manner as atrial fibrillation.999 1201

Embolism Associated with Valvular Heart Disease

Oral

Patients with rheumatic mitral valve disease and concurrent atrial fibrillation, left atrial thrombus, or a history of systemic embolism: Maintain target INR of 2.5 (range 2–3).82 1201 1202

Thromboembolism Associated with Prosthetic Heart Valves

Prophylaxis

OralBase intensity of anticoagulation on type of valve prosthesis.82 330 1143 1202 In general, target INR of 2.5 (range 2–3) suggested in patients with a mechanical aortic valve; target INR of 3 (range 2.5–3.5) recommended in those with a mechanical mitral valve.82 330 1143 1202

Patients with mechanical heart valves in any position: Long-term oral anticoagulation required.330 1143 The addition of low-dose aspirin (e.g., 50–100 mg daily) is no longer routine; the decision to use aspirin should be based on thromboembolism risk, bleeding risk, and presence of an indication for antiplatelet therapy.82 1143

Patients with bioprosthetic mitral or aortic valves: 3–6 months of warfarin therapy suggested after valve insertion; after 3 months, may switch to aspirin therapy, provided patient is in normal sinus rhythm and has no other indication for therapeutic anticoagulation (e.g., atrial fibrillation, previous thromboembolism, hypercoagulable state, left ventricular dysfunction).82 330 1143

Following transcatheter aortic valve implantation, the decision to select dual antiplatelet therapy or warfarin during the first 3–6 months, if the patient has a low risk of bleeding, should be individualized.1143

STEMI

Secondary Prevention

OralPatients at high risk of systemic or pulmonary embolism (e.g., large anterior STEMI, a history of previous thromboembolism, intracardiac thrombus, atrial fibrillation, or substantial heart failure): Warfarin (INR 2–3) and aspirin therapy (≤100 mg daily) following acute STEMI is an option.330 1199

Cerebral Thromboembolism

Secondary Prevention

OralPatients with TIA or ischemic stroke and concurrent atrial fibrillation: Maintain target INR of 2.5 (range 2–3) long term, provided no contraindications to therapy exist.82 1199 1202

Warfarin is recommended in patients at high risk for recurring cerebral embolism from other cardiac sources (e.g., prosthetic mechanical heart valves, anterior MI, and left ventricular thrombus).82 1010 1199 1202

Patients with acute cerebral venous sinus thrombosis†: Target INR is 2–3 and recommended duration of therapy is based on known or unknown provocation and the presence or absence of thrombophilia.1175

HIT†

Conversion to Warfarin Therapy†

OralInitiate warfarin only after substantial recovery from acute HIT has occurred (i.e., platelet counts ≥150,000/mm3).1168 1203

Overlap therapy with a nonheparin anticoagulant for ≥5 days until desired INR is achieved.1168 1203

Maintain target INR of 2.5 (range 2–3).1168 1203

Pharmacogenomic Considerationg in Dosing

Variations in genes responsible for warfarin metabolism or pharmacodynamic response may affect dosage requirements. 330 378 462 463 464 465 466 467 469 1178

Lower dosages may be required to avoid excessive anticoagulation (e.g., INR >3) and bleeding in patients with variations in CYP2C9 and VKORC1.330 462 464 465 466 467 469 474 1178

Genetic information does not replace regular INR monitoring and results of genetic testing should not delay initiation of warfarin therapy.473

Additional information about pharmacogenetic testing can be found at the Genetic Testing Registry ([Web]).1178

Transferring from Parenteral Anticoagulants to Warfarin

When warfarin is indicated for follow-up therapy after initial therapy with a parenteral anticoagulant (e.g., heparin, LMWH, fondaparinux), overlap therapy until adequate warfarin response obtained as indicated by INR monitoring.330 1000 1200

Manufacturers recommend that heparin and warfarin be used concurrently for ≥4–5 days until the desired INR has been achieved.330

In adults with acute DVT or PE, ACCP and ASH recommend that heparin, LMWH, or fondaparinux be used concurrently with warfarin for ≥5 days and until INR is ≥2 for ≥24 hours.1006 1200

In children with VTE† in whom long-term warfarin therapy is being considered, ACCP recommends that warfarin be initiated on the same day as heparin or LMWH; overlap such therapy for ≥5 days and until the INR is therapeutic.1013

When warfarin is used for follow-up therapy after a nonheparin anticoagulant (e.g., argatroban, bivalirudin, fondaparinux) in patients with HIT†, overlap therapy for ≥5 days until adequate warfarin response is obtained as indicated by INR.1203 Initiate warfarin therapy only after substantial recovery from acute HIT has occurred (i.e., stable platelet counts ≥150,000/mm3 or platelet recovery >50% of baseline).1203 Do not use a warfarin loading dose in HIT patients.392 1168 1203

Conversion from argatroban to warfarin is more complex than with other nonheparin anticoagulants since combined therapy with argatroban and warfarin prolongs the INR beyond that produced by warfarin alone.392 Consult manufacturer's prescribing information for specific guidelines for conversion.392 Monitor INR daily during concurrent argatroban and warfarin therapy.392

Transferring from Other Anticoagulants to Warfarin

The manufacturer suggests consulting the labeling of other anticoagulants for instructions on conversion to warfarin.330

Managing Anticoagulation in Patients Requiring Invasive Procedures

Temporary interruption of warfarin therapy may be required in patients undergoing surgery or other invasive procedures to minimize risk of perioperative bleeding.330 1004

Assess risk of thromboembolism versus risk of perioperative bleeding to determine whether interruption of therapy is necessary.1004 Temporary interruption of therapy usually required for major surgical or invasive procedures, but may not be necessary for minor procedures associated with a low bleeding risk (e.g., minor dental procedures, minor dermatologic procedures, cataract surgery).1004

If temporary interruption of warfarin necessary prior to surgery, discontinue at least 5 days prior to procedure.1004 Elderly patients with comorbidities, patients with low dose warfarin requirements, and those with a higher target INR range are among those who may require >5 days of warfarin interruption prior to surgery.1004

Determine the INR immediately prior to any invasive procedure.330

May resume warfarin therapy within 24 hours postoperatively, usually on the evening of the surgery or procedure, when adequate hemostasis is achieved.1004 Resume at the patient’s established maintenance dosage; loading doses (e.g., double the established maintenance dose) are not recommended.1004

Heparin bridging is defined as administration of an LMWH or IV heparin during the period of warfarin interruption.1004 ACCP recommends against heparin bridging in patients with mechanical heart valves, atrial fibrillation, or VTE who are not considered to be high-risk for thromboembolism when warfarin is interrupted for an elective surgery or procedure.1004 ACCP states that heparin bridging is recommended for patients at the highest risk for thromboembolism (e.g., patients with older-generation [e.g., tilting-disc] mechanical heart valves, any mechanical mitral valve, thromboembolic event within the last 3 months, atrial fibrillation patients with a CHA2DS2VASc score ≥7 or CHADS2 score ≥5).1004

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

The manufacturer makes no specific dosage recommendations; monitor more frequently for bleeding.330

Renal Impairment

The manufacturer makes no specific dosage recommendations; more frequent INR monitoring may be required.330

Geriatric Use

In patients >60 years of age, consider lower initial and maintenance dosages.330 More frequent monitoring may be necessary.330

Debilitated Patients

Consider lower initial and maintenance dosages.330

Asian Patients

May require lower initial and maintenance dosages.330

Black Patients

The CYP2C9 *5, *6, *8, and *11 alleles associated with reduced enzymatic activity and warfarin metabolism occur in 45–50% of patients with self-reported African ancestry.330 1178

The 2017 update of the CPIC guideline for pharmacogenetics-guided warfarin dosing suggests a 15–30% warfarin dosage reduction when CYP2C9 *5, *6, *8, and *11 variant alleles are detected, regardless of self-reported ancestry.1178

Cautions for Warfarin

Contraindications

-

Pregnancy, except in patients with mechanical heart valves.330

-

Patients with hemorrhagic tendencies or blood dyscrasias.330

-

Recent or contemplated surgery of the eye or CNS and in those undergoing traumatic surgery resulting in large open surfaces.330

-

Bleeding tendencies associated with active ulceration or overt bleeding of the GI, respiratory, or genitourinary tract; CNS hemorrhage; aneurysms (cerebral, dissecting aorta); pericarditis and pericardial effusions; bacterial endocarditis.330

-

Threatened abortion, eclampsia, and preeclampsia.330

-

Unsupervised patients with conditions associated with a potential high level of non-compliance with therapy (e.g., dementia/senility).330

-

Known hypersensitivity (e.g., anaphylaxis).330

-

Spinal puncture and other diagnostic or therapeutic procedures associated with the potential for uncontrollable bleeding.330

-

Major regional or lumbar block anesthesia.330

-

Malignant hypertension.330

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Bleeding Risk

Risk of serious, potentially fatal, bleeding.330 (See Boxed Warning.)

Promptly evaluate if any manifestations of blood loss occur during therapy.330

More likely to occur during the initiation of therapy and with higher dosages, resulting in higher INRs.330

Risk factors for bleeding include higher dosages, high intensity of anticoagulation (INR >4), age ≥65 years, highly variable INRs, history of GI bleeding, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, anemia, malignancy, trauma, renal or liver impairment, alcohol abuse, prior stroke, certain genetic factors, concomitant drugs that may increase INR response, and a long duration of warfarin therapy.330 462 466 474 1014

Bleeding may still occur when the INR is in the usual therapeutic range.330

GI or urinary tract bleeding may warrant investigation of underlying malignancy or other correctable lesions.1014

In patients with major bleeding requiring urgent warfarin reversal, ACCP and the ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway suggest the use of 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate (INR-based dose [e.g., 25, 35 or 50 units/kg] or fixed dose [e.g., 1000 units, 1500 units]) rather than fresh frozen plasma (FFP); additional use of vitamin K (5–10 mg by slow IV infusion) recommended.1000 1182

Other Warnings and Precautions

Tissue Necrosis

Tissue necrosis and/or gangrene of skin or other tissues reported rarely.203 215 290 291 292 293 298 330 1183

Appears early within 1–10 days after initiation of therapy principally at sites of fat tissue (e.g., abdomen, breasts, buttocks, hips, thighs); reported more frequently in women.203 290 293 298 330 1183

Increased risk in patients with hereditary, familial, or clinical deficiencies of protein C or its cofactor, protein S.290 330 1183

Careful clinical evaluation is required to determine whether necrosis is caused by underlying disease.330

Discontinue warfarin if tissue necrosis occurs; suggested treatments include supportive care, surgical debridement, aggressive wound care, and topical bactericidal agents.330 1183 Consider alternative anticoagulants.330

Systemic Atheroemboli and Cholesterol Microemboli

May result from possible increased release of atheromatous plaque emboli; some cases have progressed to necrosis and death.216 221 284 285 286 287 288 330 May occur 3–10 weeks or later following initiation of warfarin therapy.203 216 284 289 330

The most common visceral organs involved are the kidneys, followed by the pancreas, spleen, and liver. 330 Signs and symptoms vary depending on the site of embolization.330

A distinct syndrome resulting from microemboli to the feet is known as ”purple toes syndrome.”330

If signs and symptoms are observed, discontinue warfarin and consider an alternative anticoagulant.330

Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis or calcium uremic arteriolopathy in patients with and without end stage renal disease reported; may be serious and/or fatal.330 1184

Occurs after a prolonged duration of therapy compared to warfarin-induced necrosis, which occurs typically within the first 10 days.1184

Discontinue warfarin, treat calciphylaxis as appropriate, and consider alternative anticoagulants.330 1184

Acute Kidney Injury

May occur in patients with altered glomerular integrity or with a history of kidney disease, possibly in relation to episodes of excessive anticoagulation and hematuria.330

Monitor patients with compromised renal function more frequently.330

Limb Ischemia, Necrosis, and Gangrene in Patients with HIT and HITTS

Do not use warfarin as initial therapy for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) or HIT with thrombosis syndrome (HITTS).330 1168 1203

Cases of limb ischemia, necrosis, and gangrene have occurred in patients with HIT and HITTS when warfarin was initiated or continued after heparin discontinuance.330 387 388 389 395 1168

Amputation of the involved area and/or death have occurred.330 1168

Delay warfarin initiation until thrombin generation is adequately controlled and thrombocytopenia has resolved (i.e., platelet counts ≥150,000/mm3 and stable).330 354 442 444 1168 1203

Use in Pregnant Women with Mechanical Heart Valves

Possible teratogenicity, fetal or neonatal hemorrhage, and intrauterine death.330

Warfarin is generally contraindicated during pregnancy, but in women with mechanical heart valves at high risk of thromboembolism, manufacturer states the potential benefits of using warfarin may outweigh fetal risks.330

If used during pregnancy, or if the patient becomes pregnant while taking warfarin, apprise patient of the potential fetal hazard.330

Other Clinical Settings with Increased Risks

Utilize clinical judgment after weighing risks versus benefits of warfarin in the following situations: moderate to severe hepatic or renal impairment, infectious diseases (e.g., patients receiving antibiotic therapy) or disturbances of intestinal flora (e.g., sprue), patients with indwelling catheters, moderate to severe hypertension, acquired or hereditary protein C or protein S deficiencies, polycythemia vera, diabetes mellitus, eye surgery, and vasculitis.330

Although diabetes mellitus is listed, this should be interpreted with caution because diabetes is a prominent factor in stroke scoring tools (e.g., CHA2DS2VASc, ATRIA), but it is a less consistent risk factor for bleeding.330 1186 1187 1190

The manufacturer states cataract surgery in patients taking warfarin has resulted in minor complications of sharp needle and local anesthesia block but has not been associated with potentially sight-threatening operative hemorrhagic complications.330 1004 The decision to discontinue or reduce the warfarin dosage prior to less invasive or less complex eye surgery should be based on the patient’s risk of thromboembolism.330 1004

Endogenous Factors Affecting INR

Endogenous factors associated with increased INR response include diarrhea, hepatic disorders, poor nutritional state, steatorrhea, and vitamin K deficiency.330 Other factors have been reported in the literature (e.g., decompensated heart failure, non-euthyroid hyperthyroidism).1014

Endogenous factors associated with decreased INR response include increased vitamin K intake or hereditary warfarin resistance.330 Other factors have been reported in the literature (e.g., alcoholism following chronic ingestion, non-euthyroid hypothyroidism).1014

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

May cause fetal harm.330

Contraindicated during pregnancy, but in women with mechanical heart valves at high risk of thromboembolism, the manufacturer states the potential benefits of using warfarin may outweigh fetal risks.330

Multiple strategies to reduce and balance the maternal (e.g., valve thrombosis, death) and fetal risks (e.g., fetal loss, teratogenicity) are based on factors such as daily warfarin dosage, ability to utilize heparin or LMWH, ability to conduct frequent laboratory monitoring, and the patient's values and priorities.1143 1185

No single anticoagulation strategy is optimally safe for both the mother and the fetus; maternal and fetal risks can be reduced, but not eliminated.1143

Consult ACC/AHA guidelines for recommendations on the management of women with mechanical heart valves who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant.1143

Consult other guidance documents (e.g., American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], American Society of Hematology [ASH]) for management of other warfarin indications in the context of pregnancy.1125 1126 1188

Lactation

Not significantly distributed into human breast milk or detectable in plasma of nursing infants; prolonged PT/INRs reported in some infants, but substantial coagulation abnormalities not observed.330 414 1125 1126 1188 1189

ACOG, ASH, American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), ACCP, and other experts consider warfarin therapy to be compatible with breast-feeding.414 1012 1125 1126 1188

Neonates are particularly sensitive to the effects of warfarin as a result of vitamin K deficiency.330 Monitor infants receiving human milk for bruising and bleeding.330

Females and Males of Reproductive Potential

Counsel females of reproductive potential on potential risks to fetus and use of effective contraception.330

Such patients should use effective contraception during treatment and for at least 1 month after the final dose.330

Pediatric Use

Lack of adequate, well-controlled studies to inform optimum dosing, safety, and efficacy in pediatric patients.330

Use based on adult data and recommendations, as well as limited pediatric data from observational studies and patient registries.330 1013 1118

Has been used in pediatric patients for prevention and treatment of thromboembolic events.1013 1118 More frequent determinations of INR are recommended in pediatric patients.330 1013

Variable bleeding rates observed; pediatric patients should avoid activities or sports that may result in traumatic injury.330 1013

Geriatric Use

Increased sensitivity and anticoagulant response.330

Increasing age confers increasing bleeding outcomes.1186 1187 1190 1191

Consider lower initial and maintenance doses for elderly and/or debilitated patients.330 Conduct more frequent monitoring.330

Hepatic Impairment

Increased anticoagulant response due to decreased synthesis of coagulation factors and decreased metabolism of warfarin.330 330

Conduct more frequent monitoring for bleeding.330

Renal Impairment

Renal clearance considered a minor determinant of anticoagulant response.330

No dosage adjustment necessary.330

The manufacturer suggests increased INR monitoring.330

Common Adverse Effects

Most common adverse effects: fatal and nonfatal hemorrhage from any tissue or organ.330

Drug Interactions

Drug interactions can occur via pharmacodynamic interactions (e.g., impaired hemostasis; increased or decreased intestinal synthesis or absorption of vitamin K; altered distribution or metabolism of vitamin K; increased warfarin affinity for receptor sites; decreased synthesis and/or increased catabolism of functional blood coagulation factors II, VII, IX, and X; interference with platelet function or fibrinolysis; ulcerogenic effects) or pharmacokinetic interactions (e.g., increased or decreased rate of warfarin metabolism; increased or decreased protein binding).330 Such interactions may increase or decrease response to warfarin.330

Drugs Affecting Hepatic Microsomal Enzymes

Potential pharmacokinetic interaction with inhibitors or inducers of CYP2C9, 1A2, or 3A4 (increased warfarin exposure with concomitant inhibitors, decreased warfarin exposure with concomitant inducers).330 (See Table 2.) Closely monitor INR in patients who initiate, discontinue, or change dosages of these concomitant drugs.330

list of drugs is not all-inclusive

|

Enzyme |

Inhibitors* |

Inducers* |

|---|---|---|

|

CYP2C9 |

amiodarone |

aprepitant |

|

capecitabine |

bosentan |

|

|

co-trimoxazole |

carbamazepine |

|

|

etravirine |

phenobarbital |

|

|

fluconazole |

rifampin |

|

|

fluvastatin |

||

|

fluvoxamine |

||

|

metronidazole |

||

|

miconazole |

||

|

oxandrolone |

||

|

tigecycline |

||

|

voriconazole |

||

|

zafirlukast |

||

|

CYP1A2 |

acyclovir |

montelukast |

|

allopurinol |

moricizine |

|

|

caffeine |

omeprazole |

|

|

cimetidine |

phenobarbital |

|

|

ciprofloxacin |

phenytoin |

|

|

disulfiram |

cigarette smoking |

|

|

enoxacin |

||

|

famotidine |

||

|

fluvoxamine |

||

|

methoxsalen |

||

|

mexiletine |

||

|

oral contraceptives |

||

|

propafenone |

||

|

propranolol |

||

|

terbinafine |

||

|

thiabendazole |

||

|

ticlopidine |

||

|

verapamil |

||

|

zileuton |

||

|

CYP3A4 |

alprazolam |

armodafinil |

|

amiodarone |

amprenavir |

|

|

amlodipine |

aprepitant |

|

|

amprenavir |

bosentan |

|

|

aprepitant |

carbamazepine |

|

|

atorvastatin |

efavirenz |

|

|

atazanavir |

etravirine |

|

|

bicalutamide |

modafinil |

|

|

cilostazol |

nafcillin |

|

|

cimetidine |

phenytoin |

|

|

ciprofloxacin |

pioglitazone |

|

|

clarithromycin |

prednisone |

|

|

conivaptan |

rifampin |

|

|

cyclosporine |

rufinamide |

|

|

darunavir/ritonavir |

||

|

diltiazem |

||

|

erythromycin |

||

|

fluconazole |

||

|

fluoxetine |

||

|

fluvoxamine |

||

|

fosamprenavir |

||

|

imatinib |

||

|

indinavir |

||

|

isoniazid |

||

|

itraconazole |

||

|

ketoconazole |

||

|

lopinavir/ritonavir |

||

|

nefazodone |

||

|

nelfinavir |

||

|

nilotinib |

||

|

oral contraceptives |

||

|

posaconazole |

||

|

ranitidine |

||

|

ranolazine |

||

|

ritonavir |

||

|

saquinavir |

||

|

tipranavir |

||

|

voriconazole |

||

|

zileuton |

Protein-bound Drugs

Drugs may competitively or noncompetitively interfere with protein binding and unbound warfarin may increase temporarily due to concomitant plasma half-life and renal clearance changes.1192 1193

Marginal change in INR is transient.1192

Drugs that Increase Risk of Bleeding

Possible increased risk of bleeding with concomitant use of antiplatelet agents, NSAIAs, SSRIs, and anticoagulants other than warfarin.330 (See Table 3.)

Monitor closely.330 While the manufacturers of warfarin suggest close monitoring in those receiving NSAIAs, including selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, and others recommend gastroprotective agents when the combination cannot be avoided, some experts (ACCP) suggest that such concomitant therapy be avoided.1000 1192 1193

list of drugs is not all-inclusive

|

Drug Class |

Specific Drugs |

|---|---|

|

Anticoagulants |

argatroban, dabigatran, bivalirudin, heparin, fondaparinux, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, rivaroxaban, enoxaparin |

|

Antiplatelet agents |

aspirin, cilostazol, clopidogrel, dipyridamole, prasugrel, ticlopidine, ticagrelor, vorapaxar |

|

NSAIAs |

celecoxib, diclofenac, diflunisal, fenoprofen, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketoprofen, ketorolac, mefenamic acid, naproxen, oxaprozin, piroxicam, sulindac |

|

Serotonin-reuptake inhibitors |

citalopram, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, milnacipran, paroxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine, vilazodone |

Antibiotics or Antifungal Agents

Potential alteration in INR with concomitant use of certain antibiotics or antifungal agents; however, studies have not shown consistent effects on plasma warfarin concentrations.330 1192

Monitor INR closely when initiating or discontinuing any antibiotic or antifungal agent in patients receiving warfarin.330 1192 1193

Dietary or Herbal Supplements

Concomitant therapy with dietary or herbal (botanical) supplements may alter an individual’s response to warfarin therapy.330 1192 1197 (See Tables 4 and 5.) Limited information is available regarding the interaction potential of dietary and herbal products.330 1192 1197 Exercise caution and perform additional PT/INR determinations whenever these products1192 are added or discontinued.330 1197

|

agrimony |

chamomile (German and Roman) |

parsley |

|

alfalfa |

clove |

passion flower |

|

aloe gel |

*cranberry |

pau d’arco |

|

Angelica sinensis (dong quai) |

dandelion |

policosanol |

|

aniseed |

fenugreek |

poplar |

|

arnica |

feverfew |

prickly ash (Northern) |

|

asa foetida |

garlic |

quassia |

|

aspen |

German sarsaparilla |

red clover |

|

black cohosh |

ginger |

senega |

|

black haw |

Ginkgo biloba |

sweet clover |

|

bladder wrack (Fucus) |

ginseng (Panax) |

sweet woodruff |

|

bogbean |

horse chestnut |

tamarind |

|

boldo |

horseradish |

tonka beans |

|

bromelains |

inositol nicotinate |

wild carrot |

|

buchu |

licorice |

wild lettuce |

|

capsicum |

meadowsweet |

willow |

|

cassia |

nettle |

wintergreen |

|

celery |

onion |

|

agrimony |

goldenseal |

St. John’s wort |

|

coenzyme Q10 (ubidecarenone) |

mistletoe |

yarrow |

|

ginseng (Panax) |

Possible interaction between warfarin and cranberry juice (i.e., increased effect and possible increased risk of bleeding).501 502 503 504 505 506 510 1197 1198 Available data do not appear to support a clinically important interaction between warfarin and moderate cranberry juice (240–480 mL) or cranberry extract (≤1,350 mg/day) consumption; monitor closely for changes in INR and manifestations of bleeding.501 502 507 509 510 1198

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Acetaminophen |

Potential for increased anticoagulant effects;307 310 312 313 1014 however, conflicting data exist regarding clinical importance90 304 305 306 308 311 1196 |

Monitoring of INR recommended following initiation of, and during sustained therapy with large (>1.5 g daily) acetaminophen doses322 1014 1192 1196 |

|

Alcohol |

Moderate amounts (300–600 mL wine daily) did not alter warfarin plasma concentrations or hypoprothrombinemic effect in healthy young men;492 493 effects of moderate consumption (e.g., 1–2 drinks daily)486 in patients receiving long-term therapeutic anticoagulation not well studied486 490 494 495 1197 Acute ingestion of alcohol may enhance warfarin hypoprothrombinemc effect;486 490 494 495 long-term alcohol use (e.g., chronic alcoholism) associated with reduced warfarin effect through increased metabolism486 490 494 Antiplatelet effect of alcohol may increase bleeding risk without effects on INR487 |

Some clinicians recommend avoidance of concomitant alcohol ingestion485 486 Other clinicians suggest limiting alcohol consumption to small amounts (e.g., 1–2 drinks occasionally)487 during warfarin therapy487 and recommend against chronic heavy consumption (e.g., >720 mL beer, >300 mL wine, >60 mL liquor daily) |

|

Antiplatelet agents |

Increased risk of bleeding1000 |

ACCP suggests avoiding concomitant use unless benefit is known or is highly likely to exceed potential harm from bleeding1000 1192 1193 |

|

Capecitabine |

Inhibits CYP2C9 isoenzyme and decreases warfarin metabolism Possible increased anticoagulant response, increased PT/INR, and/or potentially fatal bleeding episodes, especially in patients >60 years of age with cancer |

Use concomitantly with caution Frequent monitoring of PT/INR recommended to facilitate anticoagulant dosage adjustments |

|

Cholestyramine |

Potential for decreased warfarin absorption and decreased warfarin half-life322 1192 1194 |

If concurrent use of cholestyramine and warfarin cannot be avoided, administer warfarin 1 hour before or ≥4 to 6 hours after cholestyramine1194 |

|

Lomitapide |

Increased exposure to warfarin and increased INR |

Manufacturer of lomitapide suggests monitoring INR regularly, particularly following adjustments in lomitapide dosage, and adjusting warfarin dosage as clinically indicated |

|

Miconazole (vaginal) |

Potential for increased PT/INR and/or bleeding330 362 363 364 1192 |

Monitoring PT/INR and appropriate dosage adjustments recommended with concomitant intravaginal miconazole therapy363 364 |

|

NSAIAs |

Potential for platelet aggregation inhibition, GI bleeding and peptic ulceration and/or perforation, altered PT/INR330 |

Manufacturer recommends close monitoring;330 ACCP suggests avoiding concomitant use unless benefit is known or is highly likely to exceed potential harm from bleeding1000 1192 1193 |

|

Oxandrolone |

Potential for increased warfarin half-life and AUC Potential increased PT/INR and bleeding; necessary warfarin dosage reduction may be as high as 80% |

When oxandrolone therapy is initiated, changed, or discontinued, close monitoring of PT/INR and clinical response recommended to facilitate warfarin dosage adjustments and reduce bleeding risk |

Warfarin Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Essentially completely absorbed after oral administration; peak plasma concentration usually attained within 4 hours.330

Onset

Synthesis of vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors is affected soon after absorption (e.g., within 24 hours).330 Depletion of circulating functional coagulation factors must occur before therapeutic effects of the drug become apparent.330

Duration

2–5 days after a single dose.330

Distribution

Extent

The apparent volume of distribution is about 0.14 L/kg.330

Crosses the placental barrier; however, the drug has not been detected in human breast milk.330

Plasma Protein Binding

Approximately 99%.330

Elimination

Metabolism

Almost entirely in the liver.330 Principally by CYP2C9; CYP2C19, 2C8, 2C18, 1A2, and 3A4 involved to a lesser degree.330

Elimination Route

Excreted principally in urine as metabolites.330

Half-life

Effective half-life averages 40 hours (range: 20–60 hours).330

Special Populations

Slightly decreased clearance of R-warfarin in geriatric patients compared with that in younger individuals.330 However, similar pharmacokinetics of racemic warfarin and S-warfarin in geriatric and younger individuals.330

Decreased metabolism in patients with hepatic dysfunction.330

Stability

Storage

Oral

Tablets

20–25°C.330

Protect from light.330

Actions

-

A coumarin-derivative anticoagulant.330

-

A racemic mixture of the 2 optical isomers of the drug.330

-

An indirect-acting anticoagulant; interferes with the hepatic synthesis of vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors II, VII, IX, and X.330 Also inhibits the anticoagulant proteins C and S.330

-

Interferes with the action of reduced vitamin K, which is necessary for the γ-carboxylation of several glutamic acid residues in the precursor proteins of these coagulation factors.330 Inhibits clotting factor synthesis by inhibiting the regeneration of reduced vitamin K from vitamin K epoxide via inhibition of vitamin K epoxide reductase.464 1176

-

Sequential depletion of circulating functional coagulation factor VII, protein C, factor IX, protein S, factor X, and finally factor II.330

-

Vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors physiologically decreased in neonates compared with adults; thrombin generation after warfarin therapy delayed and reduced in children compared with adults.496 497 1013

-

Antithrombogenic effects generally occur only after functional coagulation factors IX and X are diminished (usually 5–10 days following initiation of therapy).1176 1177

-

Does not alter catabolism of blood coagulation factors.1176

-

Inhibits thrombus formation when stasis is induced; may prevent extension of existing thrombi.330 1176 No direct effect on established thrombi.330

-

Phytonadione (vitamin K1) reverses the anticoagulant effect.330

Advice to Patients

-

Inform patients to strictly adhere to the prescribed dosage schedule and to not discontinue therapy without first consulting a healthcare provider.330

-

Inform patients that if a dose is missed, it should be taken as soon as possible on the same day; resume the regular dosing schedule the following day.330 Do not double a dose to make up for a missed dose.330

-

Inform patients that INR tests must be obtained based on their healthcare provider’s recommendations and regular visits are necessary.330 Instruct patients that their healthcare provider will decide what INR goal is appropriate and adjust the warfarin dosage based on the INR results.330

-

Advise patients that if warfarin is discontinued, the anticoagulant effects may persist for 2–5 days.330

-

Inform patients that they may bruise and/or bleed more easily and that a longer than normal time may be required to stop bleeding when taking warfarin.330 Instruct patients to tell their healthcare provider about any unusual bleeding (e.g., nose bleeds, bleeding gums, heavier than normal menstrual bleeding, unexpected vaginal bleeding, pink or brown urine, red or black stools, coughing up blood, vomiting blood or material that looks like coffee grounds) or bruising during therapy.330

-

Advise patients to avoid any activity or sport that may result in traumatic injury and to tell their healthcare provider if they fall often as this may increase their risk for complications.330

-

Advise patients to eat a normal, balanced diet to maintain a consistent intake of vitamin K.330 Avoid drastic changes in dietary habits, such as eating large amounts of leafy, green vegetables.330

-

Advise patients to report any serious illness, such as severe diarrhea, infection, or fever to their healthcare provider.330

-

Advise patients to inform all healthcare providers, including dentists, about their warfarin therapy including before scheduling any medical, surgical, dental, or other invasive procedure.330

-

Advise patients to carry identification notifying others of their current warfarin therapy.330

-

Advise patients to immediately contact their healthcare provider if they experience pain and discoloration of the skin (a purple bruise-like rash) that primarily occurs on areas of the body with high fat content, such as breasts, thighs, buttocks, hips, and abdomen.330

-

Advise patients to immediately contact a healthcare provider if they experience any unusual symptoms or pain since warfarin may cause small cholesterol or atheroemboli.330 When this occurs in the feet, symptoms may include sudden cool, painful, purple discoloration of the toe(s) or forefoot.330

-

Advise patients to immediately contact a healthcare provider if any of the following occur: pain, swelling, discomfort, headache, dizziness, weakness, and fall or injury, especially if they hit their head.330

-

Advise women to inform their clinician if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.330 Effective measures to avoid pregnancy should be used while taking warfarin and for 1 month after the last dose.330

-

Advise patients to inform their clinician of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs and dietary and herbal supplements, as well as any concomitant illnesses. Instruct patients not to take or discontinue any other drug, including salicylates (e.g., aspirin and topical analgesics), other OTC drugs, and botanical (herbal) products except on advice of a healthcare provider.330

-

Advise patients of other important precautionary information.330

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer’s labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

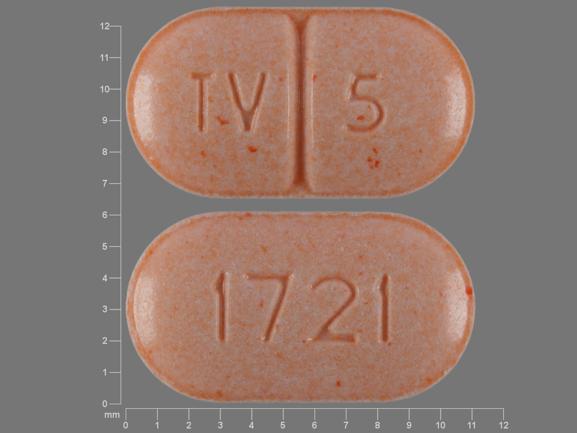

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Tablets |

1 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

||||

|

2 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

||

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

||||

|

2.5 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

||

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

||||

|

3 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

||

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

||||

|

4 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

||

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

||||

|

5 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

||

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

||||

|

6 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

||

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

||||

|

7.5 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

||

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

||||

|

10 mg* |

Jantoven (scored) |

Upsher-Smith Laboratories |

||

|

Warfarin Sodium Tablets (scored) |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions June 10, 2025. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

81. Meschia JF, Bushnell C, Boden-Albala B et al. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014; 45:3754-832. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25355838

82. Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S et al. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2021; 52:e364-e467. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34024117

83. Heidbuchel H, Verhamme P, Alings M et al. EHRA practical guide on the use of new oral anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: executive summary. Eur Heart J. 2013; 34:2094-106. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23625209

87. January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in Collaboration With the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2019; 140:e125-e151. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30686041

88. Sebaaly J, Kelley D. Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Obesity: An Updated Literature Review. Ann Pharmacother. 2020; 54:1144-1158.

89. Kido K, Lee JC, Hellwig T et al. Use of Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Morbidly Obese Patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2020; 40:72-83.

90. Koch-Weser J, Sellers EM. Drug interactions with coumarin anticoagulants (Second of two parts). New Engl J Med. 1971; 285:547-558. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4397794

203. Peterson CE, Kwaan HC. Current concepts of warfarin therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1986; 146:581-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3513725

215. Horn JR, Danziger LH, Davis RJ. Warfarin-induced skin necrosis: report of four cases. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1981; 38:1763-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7030072

216. Hyman BT, Landas SK, Ashman RF et al. Warfarin-related purple toes syndrome and cholesterol microembolization. Am J Med. 1987; 82:1233-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3605140

217. Petersen P, Boysen G, Godtfredsen J et al. Placebo-controlled, randomized trial of warfarin and aspirin for prevention of thromboembolic complications in chronic atrial fibrillation: The Copenhagen AFASAK Study. Lancet. 1989; 1:175-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2563096

218. Petersen P, Boysen G, Godtfredsen J et al. Warfarin to prevent thromboembolism in chronic atrial fibrillation. Lancet. 1989; 1:670.

221. Park S, Schroeter AL, Park YS et al. Purple toes and livido reticularis in a patient with cardiovascular disease taking coumadin: cholesterol emboli associated with coumadin therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1993; 129:777, 780. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8507086

222. Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Study Group Investigators. Preliminary report of the Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Study. N Engl J Med. 1990; 322:863-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2407959

223. The Boston Area Anticoagulation Trial for Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. The effect of low-dose warfarin on the risk of stroke in patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 1990; 323:1505-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2233931

224. Petersen P. Thromboembolic complications of atrial fibrillation and their prevention: a review. Am J Cardiol. 1990; 65:24-8C.

269. International Anticoagulant Review Group. Collaborative analysis of long-term anticoagulant administration after acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1970; 1:203-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4189006

270. A double-blind trial to assess long-term oral anticoagulant therapy in elderly patients after myocardial infarction. Report of the Sixty Plus Reinfarction Study Research Group. Lancet. 1980; 2:989-94. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6107674

271. Wintzen AR, Tijssen JGP, de Vries WA et al. Risks of long-term oral anticoagulant therapy in elderly patients after myocardial infarction: second report of the Sixty Plus reinfarction Study Research Group. Lancet. 1982; 1:64-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6119491

272. Smith P, Arnesen H, Holme I. The effect of warfarin on mortality and reinfarction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1990; 323:147-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2194126

276. Connolly SJ, Laupacis A, Gent M et al. Canadian Atrial Fibrillation Anticoagulation (CAFA) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991; 18:349-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1856403

277. Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Study. Final results. Circulation. 1991; 84:527-39. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1860198

278. Ezekowitz MD, Bridgers SL, James KE et al. Warfarin in the prevention of stroke associated with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 1992; 327:1406-12. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1406859

279. Singer DE. Randomized trials of warfarin for atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 1992; 327:1451-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1406862

280. Rothrock JF, Hart RG. Antithrombotic therapy in cerebrovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 1991; 115:885-95. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1952478

281. Albers GW, Atwood JE, Hirsh J et al. Stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 1991; 115:727-36. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1834004

282. Hirsh J. Oral anticoagulant drugs. N Engl J Med. 1991; 324:1865-75. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1801769

284. McDermaid K, Semchuk W, Duffy P. Purple toes syndrome induced by coumarin anti-coagulants. Can J Hosp Pharm. 1992; 45:205-6.

285. Acker CG. Cholesterol microembolization and stable renal function with continued anticoagulation. South Med J. 1992; 85:210-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1738893

286. Nevelsteen A, Kutten M, Lacroix H et al. Oral anticoagulant therapy: a precipitating factor in the pathogenesis of cholesterol embolization? Acta Chir Belg. 1992; 92:33-6.

287. O’Keeffe ST, Woods BO, Breslin DJ et al. Blue toe syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1992; 152:2197-202. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1444678

288. Lebsack CS, Weibert RT. “Purple toes” syndrome. Postgrad Med. 1982; 71:81-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7071041

289. Feder W, Auerbach R. “Purple toes”: an uncommon sequela of oral coumarin drug therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1961; 55:911-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13891942

290. Comp PC. Coumarin-induced skin necrosis. Incidence, mechanisms, management and avoidance. Drug Safety. 1993; 8:128-35. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8452655

291. Ansell JE. Oral anticoagulant therapy—50 years later. Arch Intern Med. 1993; 153:586-96. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8439222

292. Harrington R, Ansell J. Risk-benefit assessment of anticoagulant therapy. Drug Safety. 1991; 6:54-69. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2029354

293. Pineo GF, Hull RD. Adverse effects of coumarin anticoagulant. Drug Safety. 1993; 9:263-71. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8260120

298. Boss JM, Summerly R. Prevention of warfarin-induced skin necrosis. Br J Dermatol. 1979; 100:617. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/444435

299. Smith P, Arnesen H, Holme I. The effect of warfarin on mortality and reinfarction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1990; 323:147-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2194126

304. Antlitz AM, Mead JA, Tolentino MA. Potentiation of oral anticoagulant therapy by acetaminophen. Curr Ther Res. 1968; 10:501-507. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4971464

305. Antlitz AM, Awalt LF. A double blind study of acetaminophen used in conjunction with oral anticoagulant therapy. Curr Ther Res. 1969; 11:360-361. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4979983

306. Hartshorn EA. Drug interactions: miscellaneous analgesics. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1972; 6:50-54.

307. Hylek EM, Heiman H, Skates SJ et al. Acetaminophen and other risk factors for excessive warfarin anticoagulation. JAMA. 1998; 279:657-62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9496982

308. Kwan D, Bartle WR, Walker SE. The effects of acute and chronic acetaminophen dosing on the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of (R)- and (S)-warfarin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1995; 57:212.

310. Bartle WR, Blakely JA. Potentiation of warfarin anticoagulation by acetaminophen. JAMA. 1991; 265:1260. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1995971

311. Udall JA. Drug interference with warfarin therapy. Clin Med. 1970; 77:20-25.

312. Boeijinga JJ, Boerstra EE, Ris P. Interaction between paracetamol and coumarin anticoagulants. Lancet. 1982; 1:506. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6121161

313. Rubin RN, Mentzer RL, Budzynski AZ. Potentiation of anticoagulant effect of warfarin by acetaminophen (Tylenol). Clin Res. 1984; 32:698a.

322. Hirsh J, Dalen JE, Anderson DR et al. Oral anticoagulants. Mechanism of action, clinical effectiveness, and optimal therapeutic range. Chest. 1998; 114(Suppl):445S-69. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9822057

330. Teva Pharmaceuticals. Warfarin sodium tablets prescribing information. Parsippany, NJ; 2021 Aug..

335. Prystowsky EN, Benson W Jr, Fuster V et al. Management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a statement for healthcare professionals from the subcommittee on electrocardiography and electrophysiology, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1996; 93:1262-77. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8653857

338. Albers GW, Easton JD, Sacco RL et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke. Chest. 1998; 114:(Suppl):683-98S. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9822071

341. Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 48:598-675.

342. Chan WS, Anand S, Ginsberg JS. Anticoagulation of pregnant women with mechanical heart valves: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 2000; 160:191-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10647757

343. Elkayam U. Pregnancy through a prosthetic heart valve. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999; 33:1642-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10334436

344. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Commission on Therapeutics. ASHP therapeutic position statement on antithrombotic therapy in chronic atrial fibrillation. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1998; 55:376-81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9504198

346. Segal JB, McNamara RL, Miller MR et al. Prevention of thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of trials of anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs. J Gen Intern Med. 2000; 15:56-67. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10632835

349. Albers GW, Hart OG, Lutsep HL et al. AHA Scientific Statement. Supplement to the guidelines for the management of transient ischemic attacks. Stroke. 1999; 30:2502-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10548693

352. Wolf PA, Clagett P, Easton JD et al. Preventing ischemic stroke in patients with prior stroke and transient ischemic attack. A statement for healthcare professionals for the Stroke Council of the American Heart Association. Stroke. 1999; 30:1991-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10471455

354. Warkentin TE. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Drug Safety. 1997; 17:325-41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9391776

362. Anon. Miconazole vaginal cream and suppositories safety information. FDA Talk Paper. Rockville, MD: Food and Drug Administration; 2001 Feb 28.

363. Thirion DJG, Zanetti LAF. Potentiation of warfarin’s hypoprothrombinemic effect with miconazole vaginal suppositories. Pharmacotherapy. 2000; 20:98-99. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10641982

364. Lansdorp D, Bressers HP, Dekens-Konter JA et al. Potentiation of acenocoumarol during vaginal administration of miconazole. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999; 47:225-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10190660

369. Goldstein LB, Adams R, Becker K et al. Primary prevention of ischemic stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Stroke Council of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2001: 103:163-82.

370. Stein PD, Alpert JS, Bussey HI et al. Antithrombotic therapy in patients with mechanical and biological prosthetic heart valves. Chest. 2001: 119 (Suppl):220S-7S.

371. Salem DN, Daudelin DH, Levine HJ et al. Antithrombotic therapy in valvular heart disease. Chest. 2001; 119:207S-19S. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11157650

373. Albers GW, Amarenco P, Easton JD et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke. Chest. 2001; 119(Suppl):300S-20S. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11157656

378. Yu HCM, Chan TYK, Critchely JA et al. Factors determining the maintenance dose of warfarin in Chinese patients. Q J Med. 1996; 89:127-35.

379. Fugh-Berman A. Herb-drug interactions. Lancet. 2000; 355:134-48. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10675182

380. Spigset O. Reduced effect of warfarin caused by ubidecarenone. Lancet. 1994; 344:1372-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7968059

381. Yue QY, Bergquist C, Gerden B. Safety of St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum). Lancet. 2000; 355:576-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10683030

386. Sanofi Aventis USA. Lovenox (enoxaparin sodium) injection prescribing information. Bridgewater, NJ; 2021 Dec.

387. Greinacher A. Treatment of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Thromb Haemost. 1999; 82:457-67. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10605737

388. Kelton JG. The clinical management of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Semin Hematol. 1999; 36(Suppl. 1):17-21. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9930559