Ivermectin (Monograph)

Brand name: Stromectol

Drug class: Anthelmintics

Warning

[Posted 04/10/2020]

AUDIENCE: Consumer, Health Professional, Pharmacy, Veterinary

ISSUE: FDA is concerned about the health of consumers who may self-medicate by taking ivermectin products intended for animals, thinking they can be a substitute for ivermectin intended for humans.

BACKGROUND: The FDA's Center for Veterinary Medicine has recently become aware of increased public visibility of the antiparasitic drug ivermectin after the announcement of a research article that described the effect of ivermectin on SARS-CoV-2 in a laboratory setting. The Antiviral Research pre-publication paper, “The FDA-approved drug ivermectin inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro” documents how SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) responded to ivermectin when exposed in a petri dish.

Ivermectin is FDA-approved for use in animals for prevention of heartworm disease in some small animal species, and for treatment of certain internal and external parasites in various animal species.

RECOMMENDATION:

-

People should never take animal drugs, as the FDA has only evaluated their safety and effectiveness in the particular animal species for which they are labeled. These animal drugs can cause serious harm in people.

-

People should not take any form of ivermectin unless it has been prescribed by a licensed health care provider and is obtained through a legitimate source.

-

Ivermectin is an important part of a parasite control program for certain species and should only be given to animals for approved uses or as prescribed by a veterinarian in compliance with the requirements for extra-label drug use.

-

If you are having difficulty locating a particular ivermectin product for your animal(s), FDA recommends that you consult with your veterinarian.

For more information visit the FDA website at: [Web] and [Web].

Introduction

Anthelmintic, pediculicide, scabicide; avermectin derivative.1 4 6 14 15 18 19 33 45

Uses for Ivermectin

Pending revision, the material in this section should be considered in light of more recently available information in the MedWatch notification at the beginning of this monograph.

Ascariasis

Treatment of ascariasis† [off-label] caused by Ascaris lumbricoides.3 96 Albendazole and mebendazole are drugs of choice.2 3 80 Ivermectin also recommended as a drug of choice,2 3 but efficacy not clearly established.80

Filariasis

Treatment of onchocerciasis (filariasis caused by Onchocerca volvulus; commonly referred to as river blindness).1 2 3 6 8 17 20 21 22 42 110 116 118 Drug of choice.1 2 3 6 8 17 20 21 22 42 116 118 Used in individual patients and in mass treatment and control programs.4 5 6 7 11 16 17 19 110 116 118 119 120 Does not kill adult O. volvulus worms, but decreases microfilarial load in skin for approximately 6–12 months following a single dose.1 2 8 11 18 20 80

Treatment of filariasis caused by Mansonella streptocerca† [off-label].3 21 Diethylcarbamazine (available in US from CDC) and ivermectin are drugs of choice.3 21 Diethylcarbamazine is potentially curative since it is active against both adult worms and microfilariae; ivermectin is effective only against microfilariae.3 21 22

Has been used for treatment of filariasis caused by M. ozzardi† [off-label].3 23

Treatment of filariasis caused by Wuchereria bancrofti† [off-label] or Brugia malayi† [off-label]; used alone or in conjunction with albendazole or diethylcarbamazine (available in US from CDC).2 3 4 19 63 64 65 76 77 80 90 Ivermectin does not kill adult worms, but may play an important role in mass treatment programs to suppress microfilaremia and thereby interrupt transmission in endemic areas.80 90 Diethylcarbamazine is usual drug of choice,2 3 especially for individual patients when the goal is to kill the adult worm.80 81 82 83 90

Has been used in conjunction with albendazole to treat co-infection with W. bancrofti† and O. volvulus.76

Has been used to reduce microfilaremia in the treatment of loiasis caused by Loa loa†.3 8 35 67 Generally not recommended since rapid killing of microfilariae increases risk of encephalopathy.3 (See Encephalopathy Risk in Onchocerciasis and Loiasis under Cautions.) Drug of choice for loiasis is diethylcarbamazine (available in US from CDC);3 80 preferred alternative is albendazole since it has a slower onset of action and decreased risk of encephalopathy compared with ivermectin.3

Gnathostomiasis

Treatment of gnathostomiasis† caused by Gnathostoma spinigerum.3 Drug of choice (with or without surgical removal) is albendazole or ivermectin.3

Hookworm Infections

Treatment of cutaneous larva migrans† (creeping eruption) caused by Ancylostoma braziliense (dog and cat hookworm) or Ancylostoma caninum (dog hookworm).3 15 50 69 Usually self-limited with spontaneous cure after several weeks or months;3 15 50 69 when treatment is indicated, drug of choice is albendazole or ivermectin.15 50 69

Do not use for treatment of intestinal hookworm infections caused by Ancylostoma duodenale or Necator americanus.13 35 70 71 80 Appears to have little or no activity against these hookworms.13 35 70 71 80 Albendazole, mebendazole, and pyrantel pamoate are drugs of choice.3

Strongyloidiasis

Treatment of intestinal (i.e., nondisseminated) strongyloidiasis caused by Strongyloides stercoralis.1 2 3 Drug of choice;3 alternative is albendazole.3

Has been used for treatment of strongyloidiasis hyperinfection with disseminated disease† and for treatment of strongyloidiasis in immunocompromised patients.2 3 98 Drug of choice;2 3 alternative is albendazole.2 3 Repeated or prolonged ivermectin therapy or use with other drugs may be necessary;2 3 98 treatment failures reported.102

Empiric treatment of strongyloidiasis before transplantation to prevent hyperinfection in hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients†.9 Such treatment recommended by CDC, IDSA, ASBMT, and others for HSCT candidates with positive strongyloidiasis screening tests or possible exposure (e.g., unexplained eosinophilia and travel or residence history suggestive of S. stercoralis exposure [even if seronegative or stool-negative]).9 Data insufficient to recommend prophylaxis after HSCT to prevent recurrence of strongyloidiasis in such patients.9

Trichuriasis

Treatment of trichuriasis† caused by Trichuris trichiura (whipworm).3 96 Albendazole is drug of choice; alternatives are mebendazole and ivermectin.3

Pediculosis

Treatment of pediculosis capitis† (head lice infestation).2 3 4 14 62 107 AAP and others usually recommend topical treatment with OTC preparation of permethrin 1% or pyrethrins with piperonyl butoxide for initial treatment; other topical pediculicides (e.g., malathion 0.5%, benzyl alcohol 5%, spinosad 0.9%) recommended if OTC preparations ineffective or permethrin or pyrethrin resistance suspected.2 3 62 Oral ivermectin recommended as an alternative2 3 for infestations not responding to or resistant to topical agents.2 80

Alternative for treatment of pediculosis pubis† (pubic lice infestation).10 Drug of choice is topical permethrin 1% or topical pyrethrins with piperonyl butoxide.10

Alternative for treatment of pediculosis corporis† (body lice infestation).107 In some cases, body louse infestations may be treated by improved hygiene and by decontaminating clothes and bedding by washing at temperatures that kill lice.2 107 If infestation severe and a pediculicide necessary, use agents recommended for pediculosis capitis (i.e., topical permethrin or topical pyrethrins with piperonyl butoxide or, alternatively, other topical pediculicides or oral ivermectin).106 107

Scabies

Treatment of scabies† (mite infestation).3 4 10 32 42 46 47 52 53 68 107 108 109 111 112 CDC, AAP, and others usually recommend topical permethrin 5% as scabicide of choice;2 3 10 53 105 107 111 112 CDC also recommends oral ivermectin as a drug of choice.10

May be particularly useful in refractory scabies infestations, for control of outbreaks in institutions, and when compliance with topical therapy is difficult.10 32 42 46 47 52 53 68 107 108 109 111 112

Has been used for treatment of severe or crusted (i.e., Norwegian) scabies†.2 3 10 42 100 108 109 112 113 May be a drug of choice in immunocompromised patients.3 10 52 100 108 109 Aggressive treatment (multiple-dose oral ivermectin regimen with concomitant topical scabicide) usually necessary.10 52 108 109 113

Ivermectin Dosage and Administration

General

Onchocerciasis

-

Does not kill adult O. volvulus worms, but may decrease microfilarial load in skin for approximately 6–12 months following a single dose.1 2 8 11 18 20 80 110 Follow-up and retreatment required since adult female worms continue to produce microfilaria for 9–15 years.5 7 19

-

Recommendations for retreatment intervals vary.1 80 For individual patients, retreatment once every 6–12 months until asymptomatic has been recommended;2 3 116 intervals as short as 3 months can be considered.1 116 When used in mass treatment and control programs (community-wide mass drug administration [MDA] programs), retreatment often given at 6- or 12-month intervals;1 110 117 118 119 some programs use 3-month intervals to suppress microfilarial counts to a level where transmission can be interrupted.119 120

-

Adjunctive surgical excision of subcutaneous nodules may help eliminate microfilariae-producing adult worms,1 7 8 but there is no evidence that nodulectomies reduce blindness associated with onchocerciasis.80

Strongyloidiasis

-

After treatment, perform follow-up stool examinations to verify eradication of S. stercoralis;1 retreatment indicated if recrudescence of larvae observed.1

-

Optimal dosage for treatment of intestinal strongyloidiasis in immunocompromised (e.g., HIV-infected) patients not established.1 Several courses of therapy (i.e., at intervals of 2 weeks) may be necessary; cure may not be achieved.1 Control of extra-intestinal strongyloidiasis in such patients is difficult; once-monthly suppressive treatment may be helpful.1

Pediculosis†

-

To avoid reinfestation or transmission of lice, most experts recommend that clothing, hats, bed linen, and towels worn or used by infested individual during the 2 days prior to treatment be decontaminated (machine-washed in hot water and dried in a hot dryer).62 115

-

Items that cannot be laundered can be dry-cleaned or sealed in a plastic bag for 2 weeks.62 115

-

Decontaminate combs, brushes, and hair clips used by infested individual by soaking in hot water (>54°C) for 5–10 minutes.62 115

-

Thoroughly vacuum car seats, upholstered furniture, and floors of rooms inhabited by infested individual.62 115 Fumigation of living areas not necessary.62 115

-

Evaluate other family members and close contacts of infested individual and treat if lice infestation present.62 115 Some clinicians suggest treating family members who share a bed with infested individual, even if no live lice found on this family member.62 115 Ideally, treat all infested household members and close contacts at same time.115

-

A fine-toothed or nit comb may be used to remove any remaining nits (eggs) or nit shells from hair.62 115 Some clinicians do not consider nit removal necessary since only live lice can be transmitted, but recommend it for aesthetic reasons and to decrease diagnostic confusion and unnecessary retreatment.62 Other clinicians recommend removal of nits (especially those within 1 cm of scalp) to decrease risk of reinfestation since no pediculicide is 100% ovicidal and potentially viable nits may remain on hair after treatment.62 Although many schools will not allow children with nits to attend, AAP and other experts consider these no-nit policies excessive.62

Scabies†

-

Consider treating family members of patients with scabies since asymptomatic scabies is common.80

-

Skin eruptions at scabies infestation sites may worsen (increased lesion count and inflammation) during first few days after initiation of treatment.80 87

-

Pruritus may persist 2–4 weeks after treatment while dead mites in the outer skin layers slough off with normal exfoliation.80 87

-

HIV-infected patients with uncomplicated scabies should receive same treatment as those without HIV infection.10

-

If used for treatment of crusted scabies†, multiple-dose regimen in conjunction with a topical scabicide recommended to reduce risk of treatment failure.10 108 109 113 Immunocompromised patients, including those with HIV infection, are at increased risk of developing crusted scabies; manage such patients in consultation with an expert.10

Administration

Oral Administration

Administer orally.1 Take tablets on an empty stomach with water.1

Dosage

Pending revision, the material in this section should be considered in light of more recently available information in the MedWatch notification at the beginning of this monograph.

Pediatric Patients

Safety and efficacy not established in children weighing <15 kg.1

Ascariasis†

Ascaris lumbricoides infections†

OralChildren weighing ≥15 kg: 150–200 mcg/kg as a single dose.3

Filariasis

Onchocerciasis (Filariasis Caused by Onchocerca volvulus)

OralChildren weighing ≥15 kg: Approximately 150 mcg/kg as a single dose.1

For individual patients, retreat once every 6–12 months until asymptomatic;2 3 116 can consider intervals as short as 3 months.1 116

In international mass treatment and control programs (MDA programs), typically administered at 6- or 12-month intervals.1 117 118 119 Some (e.g., in hyperendemic areas) use 3-month intervals.119 120

|

Patient Weight (kg) |

Single Oral Dose |

|---|---|

|

15–25 |

3 mg |

|

26–44 |

6 mg |

|

45–64 |

9 mg |

|

65–84 |

12 mg |

|

≥85 |

150 mcg/kg |

Alternatively, in MDA programs, dosage is estimated based on height† since weighing recipients may be impractical (e.g., in rural areas of developing countries).80 86 88 118

|

Patient Height (cm) |

Single Oral Dose |

|---|---|

|

90–119 |

3 mg |

|

120–140 |

6 mg |

|

141–158 |

9 mg |

|

≥159 |

12 mg |

Mansonella streptocerca Infections†

OralChildren weighing ≥15 kg: 150 mcg/kg as a single dose.3

Wuchereria bancrofti Infections†

Oral150–400 mcg/kg as a single dose has been used;63 64 65 66 76 77 often used in conjunction with a single dose of albendazole or diethylcarbamazine (available in US from CDC).63 64 66 76 77

Gnathostomiasis†

Gnathostoma spinigerum Infections†

OralChildren weighing ≥15 kg: 200 mcg/kg once daily for 2 days.3

Hookworm Infections†

Cutaneous Larva Migrans (Creeping Eruption Caused by Dog and Cat Hookworms)†

OralChildren weighing ≥15 kg: 200 mcg/kg once daily for 1–2 days.3

Strongyloidiasis

Treatment of Intestinal Strongyloides stercoralis Infections

OralChildren weighing ≥15 kg: Approximately 200 mcg/kg as a single dose.1 Alternatively, some clinicians recommend 200 mcg/kg once daily for 2 days.3

Manufacturer states additional doses not generally necessary, but follow-up stool examinations required to verify eradication.1 Retreat if recrudescence of larvae observed.1

|

Patient Weight (kg) |

Single Oral Dose |

|---|---|

|

15–24 |

3 mg |

|

25–35 |

6 mg |

|

36–50 |

9 mg |

|

51–65 |

12 mg |

|

66–79 |

15 mg |

|

≥80 |

200 mcg/kg |

Prevention of Strongyloides Hyperinfection in HSCT Candidates at Risk†

OralChildren weighing ≥15 kg: 200 mcg/kg once daily for 2 days; repeat after 2 weeks.9 Complete regimen prior to HSCT.9

In immunocompromised candidates, multiple courses at 2-week intervals may be required and cure may not be achievable.9

Trichuriasis†

Trichuris trichiura Infections†

OralChildren weighing ≥15 kg: 200 mcg/kg once daily for 3 days.3

Pediculosis†

Pediculosis Capitis (Head Lice Infestation)†

OralChildren weighing ≥15 kg: 200 or 400 mcg/kg .2 3 4 5 51 62 107 Although >1 dose usually necessary, optimal number of doses and dosing interval not established.3

A 2-dose regimen of 200- or 400-mcg/kg doses given 7–10 days apart has been used.2 3 4 5 62 107

Pediculosis Pubis (Pubic Lice Infestation)†

OralA 2-dose regimen of 250-mcg/kg doses given 2 weeks apart recommended by CDC.10

Scabies†

Oral

Children weighing ≥15 kg: A 2-dose regimen of 200-mcg/kg doses given 2 weeks apart recommended by CDC.10

Others recommend 2-dose regimen of 200-mcg/kg doses given ≥7 days apart.3 68

Optimal number of doses not determined;109 2 doses usually recommended, especially in immunocompromised patients.4 5 10 32 46 47 51 52 60 108 109

Crusted (Norwegian) Scabies†

OralChildren weighing ≥15 kg: Multiple-dose regimen consisting of 200-mcg/kg doses.10 52 108 112 113 CDC and others recommend doses be given once daily on days 1, 2, 8, 9, and 15;10 113 severe cases may also require doses on days 22 and 29.10 113

Usually used in conjunction with a topical scabicide (e.g., topical benzyl benzoate 5%, topical permethrin 5%).10 113

Adults

Ascariasis†

Ascaris lumbricoides Infections†

Oral150–200 mcg/kg as a single dose.3

Filariasis

Onchocerciasis (Filariasis Caused by Onchocerca volvulus)

OralApproximately 150 mcg/kg as a single dose.1

For individual patients, retreat once every 6–12 months until asymptomatic;2 3 116 can consider intervals as short as 3 months.1 116

|

Patient Weight (kg) |

Single Oral Dose |

|---|---|

|

15–25 |

3 mg |

|

26–44 |

6 mg |

|

45–64 |

9 mg |

|

65–84 |

12 mg |

|

≥85 |

150 mcg/kg |

Alternatively, in some mass treatment and control programs, dosage is estimated based on height†; weighing recipients may be impractical (e.g., in rural areas of developing countries).80 86 88

|

Patient Height (cm) |

Single Oral Dose |

|---|---|

|

90–119 |

3 mg |

|

120–140 |

6 mg |

|

141–158 |

9 mg |

|

≥159 |

12 mg |

Mansonella Infections†

OralFilariasis caused by M. streptocerca†: 150 mcg/kg as a single dose.3

Filariasis caused by M. ozzardi†: 200 mcg/kg as a single dose has been used.3

Wuchereria bancrofti Infections†

Oral150–400 mcg/kg as a single dose has been used;63 64 65 66 76 77 often used in conjunction with a single dose of albendazole or diethylcarbamazine (available in US from CDC).63 64 66 76 77

Gnathostomiasis†

Gnathostoma spinigerum Infections†

Oral200 mcg/kg once daily for 2 days.3

Hookworm Infections†

Cutaneous Larva Migrans (Creeping Eruption Caused by Dog and Cat Hookworms)†

Oral200 mcg/kg once daily for 1–2 days.3

Strongyloidiasis

Treatment of Intestinal Strongyloides stercoralis Infections

OralApproximately 200 mcg/kg as a single dose.1 Alternatively, some clinicians recommend 200 mcg/kg once daily for 2 days.3

Manufacturer states additional doses not generally necessary, but follow-up stool examinations required to verify eradication.1 Retreat if recrudescence of larvae observed.1

|

Patient Weight (kg) |

Single Oral Dose |

|---|---|

|

15–24 |

3 mg |

|

25–35 |

6 mg |

|

36–50 |

9 mg |

|

51–65 |

12 mg |

|

66–79 |

15 mg |

|

≥80 |

200 mcg/kg |

Prevention of Strongyloides Hyperinfection in HSCT Candidates at Risk†

Oral200 mcg/kg once daily for 2 days; repeat after 2 weeks.9 Complete regimen prior to HSCT.9

In immunocompromised candidates, multiple courses at 2-week intervals may be required and cure may not be achievable.9

Trichuriasis†

Trichuris trichiura Infections†

Oral200 mcg/kg once daily for 3 days.3

Pediculosis†

Pediculosis Capitis (Head Lice Infestation)†

Oral200 or 400 mcg/kg.2 3 4 5 51 62 107 Although >1 dose usually necessary, optimal number of doses and dosing interval not established.3

A 2-dose regimen of 200- or 400-mcg/kg doses given 7–10 days apart has been used.2 3 4 5 62 107

Pediculosis Pubis (Pubic Lice Infestation)†

OralA 2-dose regimen of 250-mcg/kg doses given 2 weeks apart recommended by CDC.10

Scabies†

Oral

A 2-dose regimen of 200-mcg/kg doses given 2 weeks apart recommended by CDC.10

Others recommend 2-dose regimen of 200-mcg/kg doses given ≥7 days apart.3 68

Optimal number of doses not determined;109 2 doses usually recommended, especially in immunocompromised patients.4 5 10 32 46 47 51 52 60 108 109

Crusted (Norwegian) Scabies†

OralMultiple-dose regimen consisting of 200-mcg/kg doses.10 52 108 112 113 CDC and others recommend doses be given once daily on days 1, 2, 8, 9, and 15;10 113 severe cases may also require doses on days 22 and 29.10 113

Use in conjunction with a topical scabicide (e.g., topical benzyl benzoate 5%, topical permethrin 5%).10 113

Cautions for Ivermectin

Contraindications

Pending revision, the material in this section should be considered in light of more recently available information in the MedWatch notification at the beginning of this monograph.

-

Hypersensitivity to ivermectin or any ingredient in the formulation.1

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Mazzotti Reactions

Cutaneous and/or systemic reactions of varying severity (Mazzotti reactions) may occur in patients with onchocerciasis receiving microfilaricidal drugs (e.g., diethylcarbamazine, ivermectin).1 These may be secondary to allergic and inflammatory responses to death of microfilariae.1

Mazzotti reactions may include pruritus, edema, frank urticarial rash (papular and pustular), fever, arthralgia/synovitis, and lymph node enlargement/tenderness (e.g., axillary, cervical, inguinal).1

Mazzotti-type reactions appear to be less severe and occur less frequently with ivermectin than with diethylcarbamazine.5 6 20

These reactions may be most severe in previously untreated patients and may diminish with subsequent treatment (e.g., annual mass treatment and control programs).80

Optimal treatment of severe Mazzotti reactions not determined.1 78 Oral or IV hydration, recumbency, and/or parenteral corticosteroids have been used to treat postural hypotension;1 for supportive treatment of mild to moderate reactions, antihistamines, corticosteroids, and/or aspirin have been used.1

Mazzotti-type reactions observed with treatment of onchocerciasis or the disease itself would not be anticipated in patients being treated for strongyloidiasis.1

Ocular Effects

Ocular reactions (e.g., abnormal sensation in the eyes, eyelid edema, anterior uveitis, conjunctivitis, limbitis, keratitis, chorioretinitis or choroiditis) may occur in patients being treated for onchocerciasis or may occur secondary to the disease itself.1

Ocular reactions observed with treatment of onchocerciasis or the disease itself would not be anticipated in patients being treated for strongyloidiasis.1

Neurotoxicity

Not recommended in patients with an impaired blood-brain barrier (e.g., meningitis, African trypanosomiasis) or CNS disorders that may increase CNS penetration of the drug;4 13 91 potential interaction with CNS GABA receptors.4 13 91 (See Interactions.)

P-glycoprotein, encoded by the multi-drug resistance gene (MDR1), functions as a drug efflux transporter; appears to limit CNS uptake and prevent potentially fatal neurotoxicity.5 13 48 91 92

Theoretical increased risk of neurotoxicity in patients with altered expression or function of P-glycoprotein (e.g. through genetic polymorphism, concomitant use of inhibitors of the P-glycoprotein transport system); if such increased susceptibility exists, apparently rare.5 48 (See Interactions.)

Although not reported in humans to date, neurotoxicity (e.g., tremors, ataxia, sweating, lethargy, coma, death) has occurred in certain animals with extreme sensitivity (e.g., collie dogs, inbred strains of mice);5 48 92 increased CNS sensitivity appears to be secondary to absent or dysfunctional MDR and P-glycoprotein.5 48 92

General Precautions

Encephalopathy Risk in Onchocerciasis and Loiasis

Consider possible severe adverse effects when treating onchocerciasis in patients from areas where onchocerciasis and loiasis are co-endemic.16 54 78 79

Patients with onchocerciasis who also are heavily infected with L. loa may develop serious or fatal neurologic events (e.g., encephalopathy, coma) either spontaneously or following rapid killing of microfilariae with effective microfilaricidal agents, including ivermectin.1 3 16 54 78 79

Back pain, conjunctival hemorrhage, dyspnea, urinary and/or fecal incontinence, difficulty standing or walking, mental status changes, confusion, lethargy, stupor, seizures, coma, dysarthria or aphasia, fever, headache, or chills also reported.1 16 54 78

Reported rarely in patients receiving ivermectin, but a definite causal relationship not established.1 54 93 94

Pretreatment assessment for loiasis and careful post-treatment follow-up recommended when treatment is planned for any reason in patients with significant exposure to L. loa in endemic areas (West or Central Africa).1 16

Other Precautions in Filariasis

Increased risk of severe adverse reactions (e.g., edema, aggravation of onchodermatitis) in patients with hyperreactive onchodermatitis (sowdah).1

Does not kill adult O. volvulus worms, but decreases microfilarial load in skin for approximately 6–12 months following a single dose.1 2 8 11 18 20 80 Follow-up and retreatment required since the adult female worms continue to produce microfilaria for 9–15 years.5 7 19

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Category C.1

Has been inadvertently given to pregnant women during mass distribution campaigns for treatment and control of onchocerciasis or lymphatic filariasis, but was not associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, congenital malformations, or differences in developmental status or disease patterns in the offspring of such women.55 56 103 104

World Health Organization (WHO) and other experts state that use for treatment of onchocerciasis after the first trimester probably is acceptable based on the high risk of infection-associated blindness if untreated.104

Lactation

Distributed into milk.1 Use in nursing women only when risk of delayed treatment in the woman outweighs risks to the nursing infant.1

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy not established in children weighing <15 kg.1

Some clinicians state that use not recommended in young children (e.g., those weighing <15 kg or <2 years of age) partly because the blood-brain barrier may be less developed than in older patients.5 95 (See Neurotoxicity under Cautions.)

Limited data suggest that safety in those 6–13 years of age similar to that in adults.1

Geriatric Use

Insufficient experience in controlled clinical studies in patients ≥65 years of age to determine whether geriatric patients respond differently than younger adults.1 Other clinical experience has not revealed age-related differences in response.1

Use with caution due to greater frequency of decreased hepatic, renal, and/or cardiac function and of concomitant disease and drug therapy observed in the elderly.1

Common Adverse Effects

Treatment of onchocerciasis: Worsening of Mazzotti reactions (see Mazzotti Reactions under Cautions),1 ocular effects,1 peripheral edema,1 tachycardia,1 eosinophilia.1

Treatment of strongyloidiasis: GI effects (diarrhea,1 nausea,1 anorexia,1 constipation,1 vomiting,1 abdominal pain,1 abdominal distention),1 decreased leukocyte count,1 eosinophilia,1 increased hemoglobin,1 increased serum ALT or AST,1 nervous system effects (dizziness,1 asthenia or fatigue,1 somnolence,1 tremor,1 vertigo),1 pruritus,1 rash,1 urticaria.1

Drug Interactions

Appears to be metabolized principally by CYP3A41 41 and, to lesser extent, by 2D6 and 2E1.1 Does not inhibit CYP3A4, 2D6, 2C9, 1A2, and 2E1.1

Drugs with GABA-potentiating Activity

Concomitant use with drugs with GABA-potentiating activity (e.g., barbiturates, benzodiazepines, sodium oxybate, valproic acid) not recommended.13 80 Ivermectin may interact with GABA receptors in the CNS.2 4 13 91

Drugs Affecting or Affected by P-glycoprotein Transport

Appears to be a substrate of P-glycoprotein transport system.13 40 48 80 Theoretical possibility of interactions with inducers (e.g., amprenavir, clotrimazole, phenothiazines, rifampin, ritonavir, St. John’s wort) or inhibitors (e.g., amiodarone, carvedilol, clarithromycin, cyclosporine, erythromycin, itraconazole, ketoconazole, quinidine, ritonavir, tamoxifen, verapamil) of this system.13 40 48 80 Concomitant use with inhibitors theoretically could result in increased brain concentrations of ivermectin and neurotoxicity5 48

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Alcohol |

||

|

Anticoagulants |

Postmarketing reports of elevated INR when used concomitantly with warfarin1 |

|

|

Benzodiazepines |

Benzodiazepine effects may be potentiated13 |

Concomitant use not recommended13 |

Ivermectin Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Rapidly absorbed following oral administration; peak plasma concentrations attained in about 4 hours.1 6 14 35

Food

High-fat meal may increase absorption, but effect of food on bioavailability not evaluated using usual dosage (150–200 mcg/kg).1 33

Distribution

Extent

Concentrated in liver and adipose tissue.42

Does not readily cross blood-brain barrier.1 5 48 91 Brain uptake apparently limited by P-glycoprotein transport system.5 13 48 91 92 (See Neurotoxicity under Cautions.)

Distributed into milk in low concentrations.1

Plasma Protein Binding

Approximately 93%;75 principally albumin and, to a lesser extent, α 1-acid glycoprotein.34

Elimination

Metabolism

Metabolized in the liver,1 principally by CYP3A4.1 41

Appears to be a substrate of the P-glycoprotein transport system.40 48 49

Elimination Route

Excreted almost exclusively in feces (within approximately 12 days); <1% excreted in urine.1 14 33 35

Half-life

Approximately 18 hours following oral administration.1 33

Stability

Storage

Oral

Tablets

≤30°C.1

Actions and Spectrum

-

An avermectin-derivative anthelmintic, pediculicide, and scabicide;1 4 6 14 15 18 19 33 45 a macrocyclic lactone similar to macrolide antibacterials but possesses no antibacterial properties.14 20

-

In susceptible nematodes (roundworms), ivermectin affects ion channels in cell membranes.35 37 45

-

Binds selectively and with high affinity to glutamate-gated chloride ion channels in nerve and muscle cells of invertebrates, leading to increased cell membrane permeability to chloride ions; cellular hyperpolarization ensues, followed by paralysis and death.1 4 59

-

Also appears to interact with other ligand-gated chloride channels, such as those gated by GABA.1 4 5 14 59

-

In susceptible parasites, may interfere with the GI function resulting in starvation of the parasite.5

-

Nematodes (roundworms): Active against tissue microfilariae of Onchocerca volvulus;1 2 4 6 8 14 19 20 32 35 36 45 53 intestinal stages of Strongyloides stercoralis (threadworm);1 2 3 4 6 8 19 20 32 35 37 microfilariae of Acylostoma braziliense,4 5 6 8 14 15 35 36 A. caninum,4 5 6 14 35 36 Brugia malayi,53 Gnathostoma spinigerum,3 4 Loa loa,4 6 14 32 35 37 42 53 Mansonella streptocerca,3 21 22 42 45 53 M. ozzardi,3 22 35 42 53 and Wuchereria bancrofti;2 4 6 14 19 35 37 42 45 53 and intestinal stages of Ascaris lumbricoides6 19 35 36 37 45 and Enterobius vermicularis.20 35 37 45

-

Activity against Trichuris trichiura reported to be less than that against other nematodes.13 19 20 35 42 80 Has little or no activity against Ancylostoma duodenale,35 42 Mansonella perstans,22 35 42 45 Necator americanus,35 42 Toxocara canis,4 and T. catis.4

-

Ectoparasites: Active against adult lice, including Pediculus humanus var capitis (head louse)3 5 8 32 35 and Phthirus pubis (pubic or crab louse).3 8 Also active against the mite Sarcoptes scabiei.2 4 8 14 32 35 May have some activity against Demodex mites.4 5

-

Resistance reported in some nematodes4 obtained from livestock after extensive exposure to ivermectin;60 similar resistance not reported to date in nematodes obtained from humans.13 80

-

Although further study is needed, some data obtained from individuals in Ghana who received ivermectin in mass treatment programs of onchocerciasis (communities had received 6–18 rounds of treatment) suggest that ivermectin resistance in O. volvulus may be developing in some communities and is manifested as a more rapid return to high microfilarial load in the skin after treatment.110

-

S. scabiei with reduced ivermectin susceptibility obtained from a few patients who received multiple doses (≥30 doses) for recurrent scabies episodes;58 may represent inadequate dosage rather than actual resistance.80

Advice to Patients

Pending revision, the material in this section should be considered in light of more recently available information in the MedWatch notification at the beginning of this monograph.

-

Importance of taking on an empty stomach with water.1

-

Advise patients treated for onchocerciasis that the drug does not kill adult Onchocerca worms and that follow-up and retreatment usually is required.1

-

Advise patients treated for strongyloidiasis of the need for repeated stool examinations to document clearance of S. stercoralis infection.1

-

Importance of informing clinicians of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs and herbal products (e.g., St. John’s wort), and any concomitant or past illnesses (e.g., meningitis, African trypanosomiasis, CNS disorders).1

-

Importance of women informing their clinician if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1

-

Importance of informing patients of other important precautionary information.1 (See Cautions.)

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer’s labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

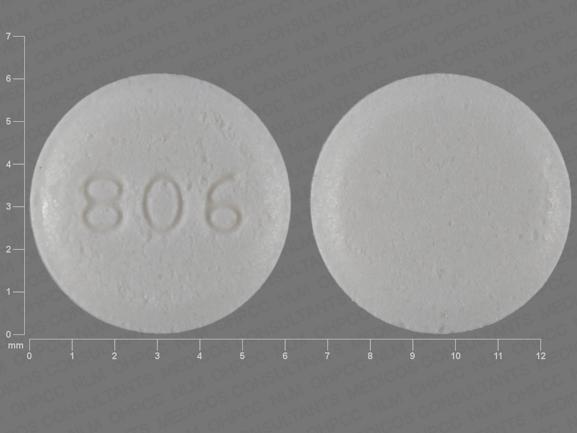

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Tablets |

3 mg |

Stromectol |

Merck |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions April 10, 2024. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

1. Merck & Co, Inc. Stromectol (ivermectin) tablets prescribing information. Whitehouse Station, NJ; 2010 May.

2. American Academy of Pediatrics. 2012 Red Book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012.

3. Anon. Drugs for parasitic infections. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2010; 8:e1-16. http://www.medletter.com

4. del Giudice P, Chosidow O, Caumes E. Ivermectin in dermatology. J Drugs Dermatol. 2003; 2:13-21. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12852376

5. Elgart GW, Meinking TL. Ivermectin. Dermatol Clin. 2003; 21:277-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12757250

6. Goa KL, McTavish D, Clissold SP. Ivermectin: review of its antifilarial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and clinical efficacy in onchocerciasis. Drugs. 1991; 42:640-58. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1723366

7. Burnham G. Onchocerciasis. Lancet. 1998; 351:1341-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9643811

8. Rosenblatt JE. Antiparasitic agents. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999; 74:1161-75. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10560606

9. Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Einsele H et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: a global perspective. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009; 15:1143-238. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19747629 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3103296/

10. Workowski KA, Berman S, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010; 59(RR-12):1-110.

11. Hoerauf A, Buttner DW, Adjei O, Pearlman E. Onchocerciasis. BMJ. 2003; 326:207-10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12543839 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1125065/

12. Ejere H, Schwartz E, Wormald R. Ivermectin for onchocercal eye disease (river blindness) (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2003. Oxford: Update Software.

13. Merck & Co., Inc., West Point, PA: Personal communication.

14. Roos TC, Alam M, Roos S, et al. Pharmacotherapy of ectoparasitic infections. Drugs. 2001; 61:1067-88. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11465870

15. Caumes E. Treatment of cutaneous larva migrans. Clin Infect Dis. 2000; 30:811-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10816151

16. Gardon J, Gardon-Wendel N, Ngangue D et al. Serious reactions after mass treatment of onchocerciasis with ivermectin in an area endemic for Loa loa infection. Lancet. 1997; 350:18-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9217715

17. Pacque M, Munoz B, Greene BM, Taylor HR. Community-based treatment of onchocerciasis with ivermectin: safety, efficacy and acceptability of yearly treatment. J Infect Dis. 1991; 163:381-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1988522

18. Greene BM, Dukuly ZD, Munoz B et al. A comparison of 6-, 12-, and 24-monthly dosing with ivermectin for treatment of onchocerciasis. J Infect Dis. 1991; 163:376-80. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1988521

19. Stephenson I, Wiselka M. Drug treatment of tropical parasitic infections. Recent achievements and developments. Drugs. 2000; 60:985-95. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11129130

20. Ette EI, Thomas WO, Achumba JI. Ivermectin: a long-acting microfilaricidal agent. DICP Ann Pharmacother. 1990; 24:426-33.

21. Fischer P, Tukesiga E, Buttner DW. Long-term suppression of Mansonella streptocerca microfilariae after treatment with ivermectin. J Infect Dis. 1999; 180:1403-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10479183

22. Fischer P, Bamuhiiga J, Buttner DW. Treatment of Mansonella streptocercainfection with ivermectin. Trop Med Int Health. 1997; 2:191-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9472305

23. Nutman TB, Nash TE, Ottesen EA. Ivermectin in the successful treatment of a patient with Mansonella ozzardi infection. J Infect Dis. 1987; 156:662-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3305722

24. Mabey D, Whitworth JA, Eckstein M, Gilbert C, Maude G, Downham M. The effects of multiple doses of ivermectin on ocular onchocerciasis. A six-year follow-up. Ophthalmology. 1996; 103:1001-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8684787

25. Barkwell R, Shields S. Deaths associated with ivermectin treatment of scabies. Lancet. 1997; 349:1144-45. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9113017

26. Tan HH, Goh CL. Parasitic skin infections in the elderly. Recognition and drug treatment. Drugs Aging. 2001; 18:165-76. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11302284

27. Alexander ND, Bockarie MJ, Kastens WA et al. Absence of ivermectin-associated excess deaths. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998; 92:342. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9861413

28. del Giudice P, Marty P, Gari-Toussaint M et al. Ivermectin in elderly patients. Arch Dermatol. 1999; 135:351-2. Letter. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10086466

29. Reintjes R, Hoek C. Deaths associated with ivermectin for scabies. Lancet. 1997; 350:215. Letter.

30. Coyne PE, Addiss DG. Deaths associated with ivermectin for scabies. Lancet. 1997; 350:215-6. Letter. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9250202

31. Diazgranados JA, Costa JL. Deaths after ivermectin treatment. Lancet. 1997; 349:1698. Letter.

32. del Giudice P. Ivermectin in scabies. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2002; 15:123-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11964911

33. Guzzo CA, Furtek CI, Porras AG et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of escalating high doses of ivermectin in healthy adult subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002; 42:1122-33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12362927

34. Okonkwo PO, Ogbuokiri JE, Ofoegbu E, Klotz U. Protein binding and ivermectin estimations in patients with onchocerciasis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1993; 53:426-30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8477558

35. Ottesen EA, Campbell WC. Ivermectin in human medicine. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994; 34:195-203. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7814280

36. Chappuis F, Farinelli T, Loutan L. Ivermectin treatment of a traveler who returned from Peru with cutaneous gnathostomiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001; 33:e17-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11462206

37. de Silva N, Guyatt H, Bundy D. Anthelmintics. A comparative review of their clinical pharmacology. Drugs. 1997; 53:769-88. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9129865

38. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Raccoon roundworm encephalitis—Chicago, Illinois, and Los Angeles, California, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002; 50:1153-5.

39. Cunningham CK, Kazacos KR, McMillan JA et al. Diagnosis and management of Baylisascaris procyonisinfection in an infant with nonfatal meningoencephalitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1994; 18:868-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8086545

40. Anon. Drug interactions. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2003; 45:46-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12789136

41. Zeng Z, Andrew NW, Arison BH et al. Identification of cytochrome P4503A4 as the major enzyme responsible for the metabolism of ivermectin by human liver microsomes. Xenobiotica. 1998; 28:313-21. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9574819

42. Moore TA. Agents active against parasites and Pneumocystis carinii. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of Infectious Diseases. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2010:631-68.

43. Shu EN, Onwujekwe EO, Okonkwo PO. Do alcoholic beverages enhance availability of ivermectin?. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000; 56:437-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11009055

44. Gonzalez AA, Chadee DD, Rawlins SC. Single dose of ivermectin to control mansonellosis in Trinidad: a four-years follow-up study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998; 92:570-1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9861384

45. Liu LX, Weller PF. Antiparasitic drugs. N Engl J Med. 1996; 334:1178-84. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8602186

46. Fawcett RS. Ivermectin use in scabies. Am Fam Physician. 2003; 68:1089-92. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14524395

47. Cook AM, Romanelli F. Ivermectin for the treatment of resistant scabies. Ann Pharmacother. 2003; 37:279-81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12549961

48. Edwards G. Ivermectin: does p-glycoprotein play a role in neurotoxicity?. Filaria J. 2003; 2 (Suppl 1):S8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14975065

49. Shapiro LE, Shear NH. Drug interactions: proteins, pumps and p-450s. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002; 47:467-84. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12271287

50. Brenner MA, Patel MB. Cutaneous larva migrans: the creeping eruption. Cutis. 2003; 72:111-115. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12953933

51. Heukelbach J, Feldmeier H. Ectoparasites–the underestimated realm. Lancet. 2004; 363:889-91. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15032237

52. Wendel K, Rompalo A. Scabies and pediculosis pubis: an update of treatment regimens and general review. Clin Infect Dis. 2002; 35 (Suppl 2):S146-51.

53. Freedman DO. Filariasis. In: Goldman L, Ausiello D, eds. Cecil textbook of medicine. 22nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004: 2118-23.

54. Twum-Danso NA. Loa loa encephalopathy temporally related to ivermectin administration reported from onchocerciasis mass treatment programs from 1989 to 2001: implications for the future. Filaria J. 2003; 2(Suppl 1):S7.

55. Pacqué M, Muñoz B, Poetschke G et al. Pregnancy outcome after inadvertent ivermectin treatment during community-based distribution. Lancet. 1990; 336:1486-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1979100

56. Gyapong JO, Chinbuah MA, Gyapong M. Inadvertent exposure of pregnant women to ivermectin and albendazole during mass drug administration. Trop Med Int Health. 2003; 8:1093-101. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14641844

58. Currie BJ, Harumal P, McKinnon M et al. First documentation of in vivo and in vitro ivermectin resistance in Sarcoptes scabiei. Clin Infect Dis. 2004; 39:e8-12. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15206075

59. Burkhart CN. Ivermectin: an assessment of its pharmacology, microbiology and safety. Vet Human Toxicol. 2000; 42:30-5.

60. Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG. Ivermectin: a few caveats are warranted before initiating therapy for scabies. Arch Dermatol. 1999; 135:1549-50. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10606071

61. Quellette M. Biochemical and molecular mechanisms of drug resistance in parasites. Trop Med Int Health. 2001; 6:874-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11703841

62. Frankowski BL, Bocchini JA, Council on School Health and Committee on Infectious Diseases. Head lice. Pediatrics. 2010; 126:392-403. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20660553

63. Beach MJ, Streit TG, Addiss DG et al. Assessment of combined ivermectin and albendazole for treatment of intestinal helminth and Wuchereria bancrofti infections in Haitian schoolchildren. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999; 60:479-86. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10466981

64. Simonsen PE, Magesa SM, Dunyo SK et al. The effect of single dose ivermectin alone or in combination with albendazole on Wuchereria bancrofti infection in primary school children in Tanzania. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2004; 98:462-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15186934

65. Brown KR, Ricci FM, Ottesen EA. Ivermectin: effectiveness in lymphatic filariasis. Parasitology. 2000; 121(Suppl):S133-46.

66. Shenoy RK, George LM, John A et al. Treatment of microfilaraemia in asymptomatic brugian filariasis: the efficacy and safety of the combination of single doses of ivermectin an diethylcarbamazine. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1998; 92:579-85. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9797831

67. Kombila M, Duong TH, Ferrer A et al. Short- and long-term action of multiple doses of ivermectin on loiasis microfilaremia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998; 58:458-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9574792

68. Meinking TL, Taplin D, Hermida JL et al. The treatment of scabies with ivermectin. N Engl J Med. 1995; 333:26-30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7776990

69. Hotez PJ, Brooker S, Bethony JM et al. Hookworm infection. N Engl J Med. 2004; 351:799-807. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15317893

70. Behnke MJ, Pritchard DI, Wakeline D et al. Effect of ivermectin on infection with gastro-intestinal nematodes in Sierra Leone. J Helminthol. 1994;68:187-95.

71. Whitworth JA, Morgan D, Maude GH et al. A field study of the effect of ivermectin on intestinal helminths in men. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991; 85:232-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1909471

72. Van den Enden E, Van Gompel A, Van der Stuyft P et al. Treatment failure of a single high dose of ivermectin for Mansonella perstans filariasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:90.

73. Keiser PB, Coulibaly YI, Keita F et al. Clinical characteristics of post-treatment reactions to ivermectin/albendazole for Wuchereria bancrofti in a region co-endemic for Mansonella perstans. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003; 69:331-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14628953

74. Fernandez MA, Ballesteros S, Aznar J. Oral anticoagulants and insecticides. Thromb Haemost. 1998; 80:724. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9799010

75. Klotz U, Ogbuokiri JE, Okonkwo PO. Ivermectin binds avidly to plasma proteins. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1990; 39:607-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2095348

76. Makunde WH, Kamugisha LM, Massaga JJ et al. Treatment of co-infection with bancroftian filariasis and onchocerciasis: a safety and efficacy study of albendazole with ivermectin compared to treatment of single infection with bancroftian filariasis. Filaria J. 2003; 2:15. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14613509 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC293471/

77. Bockarie MJ, Alexander NDE, Hyun P et al. Randomised community-based trial of annual single-dose diethylcarbamazine with or without ivermectin against Wuchereria bancrofti infection in human beings and mosquitoes. Lancet. 1998; 351:162-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9449870

78. Boussinesq M, Gardon J, Gardon-Wendel N et al. Clinical picture, epidemiology and outcome of Loa-associated serious adverse events related to mass ivermectin treatment of onchocerciasis in Cameroon. Filaria J. 2003; 2(Suppl 1):S4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14975061 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2147657/

79. Addiss DG, Rheingans R, Twum-Danso NAY et al. A framework for decision-making for mass distribution of Mectizan in areas endemic for Loa loa. Filaria J. 2003; 2(Suppl 1):S9.

80. Reviewer comments (personal observations).

81. Dreyer G, Addiss D, Noroes J et al. Ultrasonographic assessment of the adulticidal efficacy of repeat high-dose ivermectin in bancroftian filariasis. Trop Med Int Health. 1996; 1:427-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8765448

82. Dreyer G, Noroes J, Amaral F et al. Direct assessment of the adulticidal efficacy of a single dose of ivermectin in bancroftian filariasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995; 89:441-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7570894

83. Dreyer G, Addiss D, Roberts J et al. Progression of lymphatic vessel dilatation in the presence of living adult Wuchereria bancrofti. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002; 96:157-61. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12055805

84. Addiss D, Critchley J, Ejere H et al. Albendazole for lymphatic filariasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004; 1:CD003753.

85. Tielsch JM, Beeche A. Impact of ivermectin on illness and disability associated with onchocerciasis. Trop Med Int Health. 2004; 9 (Suppl):A45-56.

86. Shu EN, Okonkwo PO. Community-based ivermectin therapy for onchocerciasis: comparison of three methods of dose assessment. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001; 65:184-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11561701

87. Burkhart CG, Burkhart CN, Burkhart KM. An epidemiologic and therapeutic reassessment of scabies. Cutis. 2000; 65:233-40. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10795086

88. Gyapong J. Children eligible to receive Mectizan and albendazole for LF elimination based on height and weight criteria: case study from Kintampo District, Ghana. Mectizan Program Notes. 2004; 34:.

89. Alexander ND, Cousens SN, Yahaya H et al. Ivermectin dose assessment without weighing scales. Bull World Health Organ. 1993; 71:361-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8324855 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2393495/

90. Addiss DG, Dreyer G. Treatment of lymphatic filariasis. In: Nutman TB, ed. Lymphatic filariasis (Tropical Medicine: Science and Practice). London: Imperial College Press; 2000:151-99.

91. Tracy JW, Webster LT, Jr. Drugs used in the chemotherapy of helminthiasis. In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Gilman AG, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001:1121-40.

92. Marzolini C, Paus E, Buelin T et al. Polymorphisms in human MDR1 (p-glycoprotein): recent advances and clinical relevance. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004; 75:13-33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14749689

93. Duke BO. Overview: report of a scientific working group on serious adverse events following Mectizan treatment of onchocerciasis in Loa loa endemic areas. Filaria J. 2003; 2 (Suppl 1):S1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14975058

94. Mackenzie CD, Geary TG, Gerlach JA. Possible pathogenic pathways in the adverse clinical events seen following ivermectin administration to onchocerciasis patients. Filaria J. 2003; 2 (Suppl 1):S5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14975062

95. Heukelbach J, Winter B, Wilcke T et al. Selective mass treatment with ivermectin to control intestinal helminthiases and parasitic skin diseases in a severely affected population.. Bull World Health Organ. 2004; 82:563-71. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15375445 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2622929/

96. Belizario VY, Amarillo ME, de Leon WU et al. A comparison of the efficacy of single doses of albendazole, ivermectin, and diethylcarbamazine alone or in combinations against Ascaris and Trichuris spp. Bull World Health Org. 2003; 81:35-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12640474 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2572315/

97. Cao W, Van der Ploeg CPB, Plaisier AP et al. Ivermectin for the chemotherapy of bancroftian filariasis: a meta-analysis of the effect of single treatment. Trip Med Internat Health. 1997; 2:393-403.

98. Torres JR, Isturiz R, Murillo J et al. Efficacy of ivermectin in the treatment of strongyloidiasis complicating AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1993; 17:900-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8286637

99. Caumes E, Datry A, Paris L et al. Efficacy of ivermectin in the therapy of cutaneous larva migrans. Arch Derm. 1992; 128:994-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1626975

100. Aubin F, Humbert P. Ivermectin for crusted (norwegian) scabies. N Engl J Med. 1995; 332:612. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7838209

101. Chiodini PL, Reid AJC, Wiselka MJ et al. Parenteral ivermectin in Strongyloides hyperinfection. Lancet. 2000; 355:43-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10615895

102. Ashraf M, Gue CL, Baddour LM. Case report: strongyloidiasis refractory to treatment with ivermectin. Am J Med Sci. 1996; 311:178-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8602647

103. Makene C, Malecela-Lazaro M, Kabali C et al. Inadvertent treatment of pregnant women in the tanzanian mass drug administration program for the elimination of lymphatic filariasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003; 69(Suppl 3):277. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14628944

104. Ivermectin. In: Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Yaffe SJ. Drugs in pregnancy and lactation. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011:783-5.

105. Strong M, Johnstone P. Interventions for treating scabies . Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 207;(3):CD000320.

106. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Body lice infestation. From the CDC website. Accessed 2013 Apr 5. http://www.cdc.gov/lice/body/index.html

107. Gunning K, Pippitt K, Kiraly B et al. Pediculosis and scabies: treatment update. Am Fam Physician. 2012; 86:535-41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23062045

108. Hengge UR, Currie BJ, Jager G et al. Scabies: a ubiquitous neglected skin disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006; 6:769-79. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17123897

109. Scheinfeld N. Controlling scabies in institutional settings. A review of medications, treatment models, and implementation. Am J Dermatol. 2004; 5:31-7.

110. Osei-Atweneboana MY, Eng JKL, Boakye DA et al. Prevalence and intensity of Onchocerca volvulus infection and efficacy of ivermectin in endemic communities in Ghana: a two-phase epidemiological study. Lancet. 2007; 369:2021-9.

111. Diaz JH. Scabies. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2010:3633-6.

112. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Crusted scabies cases (single or multiple). 2010 Nov 2. From the CDC website. Accessed 2013 Mar 29. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/health_professionals/crusted.html

113. Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patients and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005; 50:375-81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15907543

114. Sanofi Pasteur Inc. Sklice (ivermectin) lotion 0.5% for topical use prescribing information. Swiftwater, PA; 2012 Feb.

115. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Head lice treatment. From CDC website. Accessed 2013 Mar 1. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/head/treatment.html

116. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Onchocerciasis. Resources for Health Professionals. From CDC website. Accessed 2013 May 24. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/onchocerciasis/health_professionals/index.html

117. World Health Organization. Onchocerciasis fact sheet. From WHO website. Accessed 2013 May 24. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs374/en/index.html

118. World Health Organization. Preventative chemotherapy in human helminthiasis. Coordinated use of anthelminthic drugs in control interventions: a manual for health professionals and programme managers. From WHO website. Accessed 2013 May 24. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2006/9241547103_eng.pdf

119. . Progress towards eliminating onchocerciasis in the WHO Region of the Americas in 2011: interruption of transmission in Guatemala and Mexico. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012; 87:309-14. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22905372

120. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Progress Toward Elimination of Onchocerciasis in the Americas - 1993-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013; 62:405-408. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23698606 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4604938/

Related/similar drugs

Frequently asked questions

- Can ivermectin be used to treat COVID-19?

- How long does it take for ivermectin to kill head lice?

- How long does it take for Sklice (ivermectin) to kill head lice?

More about ivermectin

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (54)

- Drug images

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Support group

- Drug class: anthelmintics

- Breastfeeding

- En español