Dicloxacillin (Monograph)

Drug class: Penicillinase-resistant Penicillins

Chemical name: [2S-(2α,5α,6β)]-6-[[[3-(2,6-Dichlorophenyl)-5-methyl-4-isoxazolyl]carbonyl]amino]-3,3-dimethyl-7-oxo-4-thia-1-azabicyclo[3.2.0]heptane-2-carboxylic acid monosodium salt monohydrate

CAS number: 13412-64-1

Introduction

Antibacterial; β-lactam antibiotic; isoxazolyl penicillin classified as a penicillinase-resistant penicillin.1 2 6 7 18 29 30 37

Uses for Dicloxacillin

Staphylococcal Infections

Treatment of infections caused by, or suspected of being caused by, susceptible penicillinase-resistant staphylococci.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Should not be used for initial treatment of severe, life-threatening infections, including endocarditis, but may be used as follow-up after a parenteral penicillinase-resistant penicillin (nafcillin, oxacillin).1 2 5 6 8 9

If used empirically, consider whether staphylococci resistant to penicillinase-resistant penicillins (oxacillin-resistant [methicillin-resistant] staphylococci) are prevalent in the hospital or community.a (See Staphylococci Resistant to Penicillinase-resistant Penicillins under Cautions.)

Dicloxacillin Dosage and Administration

Administration

Oral Administration

Administer orally at least 1 hour before or 2 hours after meals.1 2

Should not be used for initial treatment of severe infections and should not be relied on in patients with nausea, vomiting, gastric dilatation, cardiospasm, or intestinal hypermotility.1 2 6 9

Dosage

Available as dicloxacillin sodium; dosage expressed in terms of dicloxacillin.1 2

Duration of treatment depends on type and severity of infection and should be determined by the clinical and bacteriologic response of the patient.1 2 5 6 8 Usually continued for ≥48 hours after cultures are negative and patient becomes afebrile and asymptomatic.1 2 For severe staphylococcal infections, continue therapy for ≥14 days;1 2 5 6 more prolonged therapy is necessary for treatment of osteomyelitis, endocarditis, or other metastatic infections.1 2 5 6 13 54

Pediatric Patients

Staphylococcal Infections

Mild to Moderate Infections

OralChildren weighing <40 kg: 12.5 mg/kg daily given in divided doses every 6 hours.1 2 6 11

Children weighing ≥40 kg: 125 mg every 6 hours.1 2 6

Children ≥1 month of age: AAP recommends 25–50 mg/kg daily in 4 divided doses.9

More Severe Infections

OralChildren weighing <40 kg: 25 mg/kg daily given in divided doses every 6 hours;1 2 higher dosage may be necessary depending on severity of infection.6 11

Children weighing ≥40 kg: 250 mg every 6 hours;1 2 higher dosage may be necessary depending on severity of infection.6

Inappropriate for severe infections per AAP.9

Acute or Chronic Osteomyelitis

Oral50–100 mg/kg daily given in divided doses every 6 hours as follow-up to initial parenteral therapy.12 13 14 16 54 If an oral regimen is used, compliance must be assured and some clinicians suggest that serum bactericidal titers (SBTs) be used to monitor adequacy of therapy and adjust dosage.13 14 15 16 17 53 54

When used as follow-up in treatment of acute osteomyelitis, oral regimen usually given for 3–6 weeks or until total duration of parenteral and oral therapy is ≥6 weeks;12 13 14 16 54 when used as follow-up in treatment of chronic osteomyelitis, oral regimen usually given for ≥1–2 months and has been given for as long as 1–2 years.13 18 54

Adults

Staphylococcal Infections

Mild to Moderate Infections

OralMore Severe Infections

Oral250 mg every 6 hours;1 2 higher dosage may be necessary depending on severity of infection.6

Special Populations

Renal Impairment

Dosage adjustment generally unnecessary in patients with renal impairment.19 20 21

Cautions for Dicloxacillin

Contraindications

Warnings/Precautions

Sensitivity Reactions

Hypersensitivity Reactions

Serious and occasionally fatal hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, reported with penicillins.1 2 Anaphylaxis occurs most frequently with parenteral penicillins but has occurred with oral penicillins.1 2

Prior to initiation of therapy, make careful inquiry regarding previous hypersensitivity reactions to penicillins, cephalosporins, or other drugs.1 2 Partial cross-allergenicity occurs among penicillins and other β-lactam antibiotics including cephalosporins and cephamycins.1 2 22 23 24 25

If a severe hypersensitivity reaction occurs, discontinue immediately and institute appropriate therapy as indicated (e.g., epinephrine, corticosteroids, maintenance of an adequate airway and oxygen).1 2

General Precautions

Superinfection

Possible emergence and overgrowth of nonsusceptible bacteria or fungi.1 2 Discontinue and institute appropriate therapy if superinfection occurs.1 2

Laboratory Monitoring

Periodically assess organ system functions, including renal, hepatic, and hematopoietic, during prolonged therapy.1

Peform urinalysis and determine serum creatinine and BUN concentrations prior to and periodically during therapy.1 2

To monitor for hepatotoxicity, determine AST and ALT concentrations prior to and periodically during therapy.1 2

Because adverse hematologic effects have occurred with penicillinase-resistant penicillins, total and differential WBC counts should be performed prior to and 1–3 times weekly during therapy.1 2 5 6 26 27

Selection and Use of Anti-infectives

To reduce development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain effectiveness of dicloxacillin and other antibacterials, use only for treatment or prevention of infections proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria.

When selecting or modifying anti-infective therapy, use results of culture and in vitro susceptibility testing.1 2 In the absence of such data, consider local epidemiology and susceptibility patterns when selecting anti-infectives for empiric therapy.1 2

Staphylococci Resistant to Penicillinase-resistant Penicillins

Consider that staphylococci resistant to penicillinase-resistant penicillins (referred to as oxacillin-resistant [methicillin-resistant] staphylococci) are being reported with increasing frequency.a

If dicloxacillin used empirically for treatment of any infection suspected of being caused by staphylococci, the drug should be discontinued and appropriate anti-infective therapy substituted if the infection is found to be caused by any organism other than penicillinase-producing staphylococci susceptible to penicillinase-resistant penicillins.1 2 If staphylococci resistant to penicillinase-resistant penicillins (oxacillin-resistant staphylococci) are prevalent in the hospital or community, empiric therapy of suspected staphylococcal infections should include another appropriate anti-infective (e.g., vancomycin).a

Sodium Content

Each 250-mg capsule contains approximately 0.6 mEq of sodium.52

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Lactation

Distributed into milk.1 2 6 28 Use with caution.1 2 6

Pediatric Use

Elimination of penicillins is delayed in neonates because of immature mechanisms for renal excretion; abnormally high serum concentrations may occur in this age group.1 2 6

If used in neonates, monitor closely for clinical and laboratory evidence of toxic or adverse effects, determine serum concentrations frequently, and make appropriate reductions in dosage and frequency of administration when indicated.1 2 6

Common Adverse Effects

GI effects (nausea, vomiting, epigastric distress, loose stools, diarrhea, flatulence); hypersensitivity reactions.a

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Aminoglycosides |

In vitro evidence of synergistic antibacterial effects against penicillinase-producing and nonpenicillinase-producing S. aureusa |

|

|

Anticoagulants, oral (warfarin) |

Possible decreased hypothrombinemic effecta |

Monitor PTs and adjust anticoagulant dosage if indicateda |

|

Probenecid |

Decreased renal tubular secretion and increased and prolonged dicloxacillin plasma concentrations.1 2 a |

|

|

Tetracyclines |

Dicloxacillin Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Rapidly, but incompletely, absorbed from GI tract.1 2 7 33

35–76% of an oral dose absorbed from GI tract;33 34 35 peak serum concentrations generally attained within 0.5–2 hours.1 2 35 36

Food

Food in the GI tract generally decreases the rate and extent of absorption.1 2 4 6 7 29 35

Distribution

Extent

Distributed into bone,4 39 bile,1 2 pleural fluid,1 2 4 7 ascitic fluid,4 and synovial fluid.4 40

Only minimal concentrations attained in CSF.2

Crosses the placenta42 and is distributed into milk.1 2 6 28

Plasma Protein Binding

95–99% bound to serum proteins.1 2 7 31 34 37 41

Elimination

Metabolism

Partially metabolized to active and inactive metabolites.4 43 46 47

Approximately 10% of absorbed drug is hydrolyzed to penicilloic acids which are microbiologically inactive;46 also hydroxylated to a small extent to a microbiologically active metabolite which appears to be slightly less active than dicloxacillin.47

Elimination Route

Dicloxacillin and its metabolites rapidly eliminated in urine mainly by tubular secretion and glomerular filtration.1 2 7 29 43 47 Also partly excreted in feces via biliary elimination.4

31–65% of a dose excreted in urine as unchanged drug and active metabolites within 6–8 hours;4 31 32 34 36 46 47 approximately 10–20% of this is the active metabolite.4 47

Only minimally removed by hemodialysis4 10 20 34 43 44 49 or peritoneal dialysis.4 44 49

Half-life

Adults with normal renal function: 0.6–0.8 hours.1 2 4 33 34 43 44 45

Children 2–16 years of age: average half-life is 1.9 hours.39

Neonates: half-life is longer than in older children.4 6

Special Populations

Patients with renal impairment: serum half-life is slightly prolonged and may range from 1–2.2 hours in those with severe renal impairment.4 33 34 45

Patients with cystic fibrosis eliminate dicloxacillin approximately 3 times faster than healthy individuals.7 48

Stability

Storage

Oral

Capsules

15–30°C52 in tight containers.50

Actions and Spectrum

-

Based on spectrum of activity, classified as a penicillinase-resistant penicillin.1 2 6 7 29 30 31 32

-

Like other β-lactam antibiotics, antibacterial activity results from inhibition of bacterial cell wall synthesis.1 2

-

Spectrum of activity includes many gram-positive aerobic cocci, some gram-positive bacilli, and a few gram-negative aerobic cocci; generally inactive against gram-negative bacilli and anaerobic bacteria.a Inactive against mycobacteria, Mycoplasma, Rickettsia, fungi, and viruses.a

-

Gram-positive aerobes: active in vitro against penicillinase-producing and nonpenicillinase-producing Staphylococcus aureus and S. epidermidis, S. pyogenes (group A β-hemolytic streptococci), S. agalactiae (group B streptococci), groups C and G streptococci, S. pneumoniae, and some viridans streptococci.a Enterococci (including E. faecalis) usually are resistant.a

-

Like other penicillinase-resistant penicillins, dicloxacillin is resistant to inactivation by staphylococcal penicillinases and is active against many penicillinase-producing strains of S. aureus and S. epidermidis resistant to natural penicillins, aminopenicillins, or extended-spectrum penicillins.1 2 4 6 7 30 31 32

-

Staphylococci resistant to penicillinase-resistant penicillins (referred to as oxacillin-resistant [methicillin-resistant] staphylococci) are being reported with increasing frequency.a Complete cross-resistance occurs among the penicillinase-resistant penicillins (dicloxacillin, nafcillin, oxacillin).a

Advice to Patients

-

Advise patients that antibacterials (including dicloxacillin) should only be used to treat bacterial infections and not used to treat viral infections (e.g., the common cold).

-

Importance of completing full course of therapy, even if feeling better after a few days.1 2

-

Advise patients that skipping doses or not completing the full course of therapy may decrease effectiveness and increase the likelihood that bacteria will develop resistance and will not be treatable with dicloxacillin or other antibacterials in the future.

-

Importance of taking dicloxacillin 1 hour before or 2 hours after meals.1 2

-

Importance of discontinuing dicloxacillin and notifying clinician if they develop shortness of breath, wheezing, rash, mouth irritation, black tongue, sore throat, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, swollen joints, or any unusual bleeding or bruising during dicloxacillin treatment.1 2

-

Importance of informing clinicians of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs.1 2

-

Importance of women informing clinician if they are or plan to become pregnant or to breast-feed.1

-

Importance of informing patients of other important precautionary information. (See Cautions.)

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

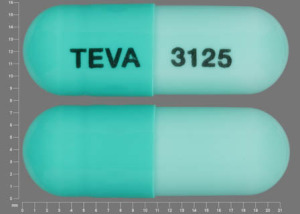

Capsules |

250 mg (of dicloxacillin)* |

Dicloxacillin Sodium |

Sandoz |

|

500 mg (of dicloxacillin)* |

Dicloxacillin Sodium |

Sandoz |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions May 1, 2004. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

References

1. Apothecon. Dicloxacillin sodium capsules, USP prescribing information. Princeton, NJ; 1995 Apr.

2. Teva Pharmaceuticals. Dicloxacillin sodium capsules, USP prescribing information. Sellersville, PA; 1997 Jul.

3. Anon. The choice of antibacterial drugs. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2001; 43:69-78. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11518876

4. Neu HC. Antistaphylococcal penicillins. Med Clin North Am. 1982; 66:51-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7038340

5. Kunin CM. Penicillinase-resistant penicillins. JAMA. 1977; 237:1605-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/576661

6. US Food and Drug Administration. Penicillinase-resistant penicillin human prescription drugs class labeling guideline for professional labeling. [Notice of availability published in: Fed Regist. 1982; 47:41636.] Available from: Professional Labeling Branch, Division of Drug Advertising and Labeling, Food and Drug Administration, Rockville, MD.

7. Kucers A, Crowe S, Grayson ML et al, eds. The use of antibiotics. A clinical review of antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral drugs. 5th ed. Jordan Hill, Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1997: 3-226.

8. Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, eds. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. 16th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 2000.

9. Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. 2000 Red book: report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 25th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1997:514-26,660.

10. Deresinski SC, Stevens DA. Clinical evaluation of parenteral dicloxacillin. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 1975; 18:151-63. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/809231

11. Gunn VL, Nechyba C, eds. The Harriet Lane handbook: a manual for pediatric house officers. 16th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby: 2002:660-1.

12. Bryson YJ, Connor JD, LeClerc M et al. High-dose dicloxacillin treatment of acute staphylococcal osteomyelitis in children. J Pediatr. 1979; 94:673-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/430319

13. Dunkle LM, Brock N. Long-term follow-up of ambulatory management of osteomyelitis. Clin Pediatr. 1982; 21:650-5.

14. Kaplan SL, Mason EO, Feigin RD. Clindamycin versus nafcillin or methicillin in the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis in children. South Med J. 1982; 75:138-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7036354

15. Waldvogel FA, Vasey H. Osteomyelitis: the past decade. N Engl J Med. 1980; 303:360-70. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6993944

16. Prober CG, Yeager AS. Use of the serum bactericidal titer to assess the adequacy of oral antibiotic therapy in the treatment of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis. J Pediatr. 1979; 95:131-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/113517

17. McCracken GH, Eikenwald HF. Antimicrobial therapy in infants and children. Part II. Therapy of infectious conditions. J Pediatr. 1978; 93:357-77. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/357692

18. Chambers HF. Penicillins. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. 5th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2000: 261-74.

19. Cheigh JS. Drug administration in renal failure. Am J Med. 1977; 62:555-63. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/851131

20. Bennett WM, Aronoff GR, Morrison G et al. Drug prescribing in renal failure: dosing guidelines for adults. Am J Kidney Dis. 1983; 3:155-93. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6356890

21. Jackson EA, McLeod DC. Pharmacokinetics and dosing of antimicrobial agents in renal impairment, part ii. AM J Hosp Pharm. 1974; 31:137-48. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4815846

22. Idsoe O, Guthe T, Willcox RR et al. Nature and extent of penicillin side-reactions, with particular reference to fatalities from anaphylactic shock. Bull World Health Organ. 1968; 38:159-88. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2554321/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5302296

23. Erffmeyer JE. Adverse reactions to penicillin. Ann Allergy. 1981; 47:288-300. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6171185

24. Isbister JP. Penicillin allergy: a review of the immunological and clinical aspects. Med J Aust. 1971; 1:1067-74. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4398272

25. Sullivan TJ, Wedner HJ, Shatz GS et al. Skin testing to detect penicillin allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1981; 68:171-80. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6267115

26. Carpenter J. Neutropenia induced by semisynthetic penicillin. South Med J. 1980; 73:745-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7394597

27. Homayouni H, Gross PA, Setia U et al. Leukopenia due to penicillin and cephalosporin homologues. Arch Intern Med. 1979; 139:827-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/454076

28. Matsuda S. Transfer of antibiotics into maternal milk. Biol Res Pregnancy. 1984; 5:57-60.

29. Marcy SM, Klein JO. The isoxazolyl penicillins: oxacillin, cloxacillin, and dicloxacillin. Med Clin North Am. 1970; 52:1127-43.

30. Selwyn S. The mechanisms and range of activity of penicillins and cephalosporins. In: Selwyn S, ed. The beta-lactam antibiotics: penicillins and cephalosporins in perspective. London: Hodder and Stoughton; 1980:56-90.

31. Gravenkemper CF, Bennett JV, Brodie JL et al. Dicloxacillin: in vitro and pharmacologic comparisons with oxacillin and cloxacillin. Arch Intern Med. 1965; 116:340-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14325906

32. Hammerstrom CF, Cox F, McHenry MC et al. Clinical, laboratory, and pharmacological studies of dicloxacillin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1966:69-74.

33. Nauta EH, Mattie H. Dicloxacillin and cloxacillin: pharmacokinetics in healthy and hemodialysis subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1976; 20:98-108. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1277730

34. Barza M, Weinstein L. Pharmacokinetics of the penicillins in man. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1976; 1:297-308. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/797501

35. Doluisio JT, LaPiana JC, Wilkinson GR et al. Pharmacokinetic interpretation of dicloxacillin levels in serum after extravascular administration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1969:49-55.

36. DeFelice EA. Serum levels, urinary recovery, and safety of dicloxacillin, a new semisynthetic penicillin, in normal volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 1967; (Sep-Oct):275-7.

37. Hou JP, Poole JW. β-Lactam antibiotics: their physiochemical properties and biological activities in relation to structure. J Pharm Sci. 1971; 60:503-27. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4336386

38. Bass JW, Bruhn FW, Merritt WT et al. Comparison of oral penicillinase-resistant penicillins: contrasts between agents and assays. South Med J. 1982; 75:408-10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7041278

39. Tetzlaff TR, Howard JB, McCracken GH et al. Antibiotic concentrations in pus and bone in children with osteomyelitis. J Pediatr. 1978; 92:135-40. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/619056

40. Nelson JD, Howard JB, Shelton S. Oral antibiotic therapy for skeletal infections of children. J Pediatr. 1978; 92:131-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/619055

41. Kunin CM. Clinical significance of protein binding of the penicillins. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1967; 145:282-90. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4998178

42. Depp R, Kind AC, Kirby WM et al. Transplacental passage of methicillin and dicloxacillin into the fetus and amniotic fluid. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970; 107:1054-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5429971

43. Bergan T. Penicillins. In: Schonfeld H, ed. Antibiotics and chemotherapy. Vol 25. Basel: S. Karger; 1978:1-122.

44. Giusti DL. A review of the clinical use of antimicrobial agents in patients with renal and hepatic insufficiency: the penicillins. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1973; 7:62-74.

45. Rosenblatt JE, Kind AC, Brodie JL et al. Mechanisms responsible for the blood level differences of isoxazolyl penicillins: oxacillin, cloxacillin, and dicloxacillin. Arch Intern Med. 1968; 121:345-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5645708

46. Cole M, Kening MD, Hewitt VA. Metabolism of penicillins to penicilloic acids and 6-aminopenicillanic acid in man and its significance in assessing penicillin absorption. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1973; 3:463-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC444435/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4364176

47. Thijssen HH, Mattie H. Active metabolites of isoxazolylpenicillins in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1976; 10:441-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC429767/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/825029

48. Jusko WJ, Mosovich LL, Gerbracht LM et al. Enhanced renal excretion of dicloxacillin in patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 1975; 56:1038-44. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1196754

49. Neu HC. Penicillins: microbiology, pharmacology, and clinical use. In: Kagan BM, ed. Antimicrobial therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1980:20-34.

50. The United States pharmacopeia, 26th rev, and The national formulary, 21st ed. Rockville, MD: The United States Pharmacopeial Convention, Inc; 2003:597-8,1261-3,1355-7,2571-2.

51. Newton DW, Kluza RB. pKa Values of medicinal compounds in pharmacy practice. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1978; 12:546-54.

52. Porter EG (Bristol Laboratories, Syracuse, NY): Personal communication; 1984 Dec 28.

53. Hedstrom SA. Treatment of chronic staphylococcal osteomyelitis with cloxacillin and dicloxacillin—a comparative study in 12 patients. Scand J Infect Dis. 1975; 7:55-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1145134

54. Armstrong EP, Rush DR. Treatment of osteomyelitis. Clin Pharm. 1983; 2:213-24. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6349907

a. AHFS Drug Information 2004. McEvoy GK, ed. Penicillinase-resistant Penicillins General Statement. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2004:328-34.

Related/similar drugs

Frequently asked questions

More about dicloxacillin

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (9)

- Drug images

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: penicillinase resistant penicillins

- Breastfeeding

- En español