Amblyopia

Medically reviewed by Drugs.com. Last updated on Aug 4, 2025.

What is amblyopia?

Amblyopia, or lazy eye, is decreased vision in one or both eyes. Amblyopia develops when your eye and brain do not work together correctly. This can cause trouble seeing. Amblyopia is often found during a routine vision test.

|

What causes amblyopia?

- Refractive error (one eye cannot focus as well as the other because of the shape)

- Strabismus (one or both eyes wander in, out, up, or down)

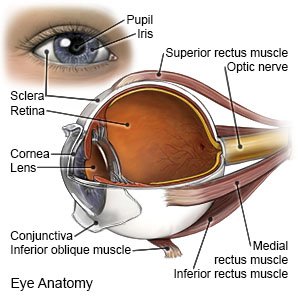

- Cataract (clouding of the lens of the eye)

What are the signs and symptoms of amblyopia?

- Squinting, covering, or closing one eye

- Rubbing the eyes

- Sitting close to screens, or the front of a room

- Eye that wanders or turns in or out

- Eyes that are not aligned, or do not move together

- Poor vision, such as not being able to see objects waved in front of you

- Tilting your head to one side to see better

How is amblyopia treated?

- An eye patch can help strengthen the weaker eye and improve your vision. The eye patch is worn over your stronger eye for 1 or more hours every day. You may need to do this for weeks or months.

- Eyedrops may be put into your stronger eye to make your vision blurry. This will help your brain use your weaker eye, which will make it stronger and improve your vision.

- Glasses or contact lenses may be recommended to correct a refractive error. This may help your vision improve.

- Surgery may be needed to correct a muscle imbalance in your eye. The eye muscles on one or both sides may be cut and reattached. This helps position the eyes so they line up correctly.

When should I call my doctor?

- Your vision suddenly gets worse or you have trouble seeing.

- You have a fever.

- You have questions or concerns about your condition or care.

Care Agreement

You have the right to help plan your care. Learn about your health condition and how it may be treated. Discuss treatment options with your healthcare providers to decide what care you want to receive. You always have the right to refuse treatment. The above information is an educational aid only. It is not intended as medical advice for individual conditions or treatments. Talk to your doctor, nurse or pharmacist before following any medical regimen to see if it is safe and effective for you.© Copyright Merative 2025 Information is for End User's use only and may not be sold, redistributed or otherwise used for commercial purposes.

Learn more about Amblyopia

Treatment options

Care guides

Further information

Always consult your healthcare provider to ensure the information displayed on this page applies to your personal circumstances.