Videx Side Effects

Generic name: didanosine

Medically reviewed by Drugs.com. Last updated on Jun 26, 2023.

Note: This document contains side effect information about didanosine. Some dosage forms listed on this page may not apply to the brand name Videx.

Applies to didanosine: oral capsule delayed release.

Warning

Oral route (Capsule, Delayed Release; Powder for Solution)

Warning: Pancreatitis, Lactic Acidosis and Hepatomegaly with SteatosisFatal and nonfatal pancreatitis has occurred during therapy with didanosine used alone or in combination regimens in both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients, regardless of degree of immunosuppression. Didanosine should be suspended in patients with suspected pancreatitis and discontinued in patients with confirmed pancreatitis.Lactic acidosis and severe hepatomegaly with steatosis, including fatal cases, have been reported with the use of nucleoside analogues alone or in combination, including didanosine and other antiretrovirals. Fatal lactic acidosis has been reported in pregnant individuals who received the combination of didanosine and stavudine with other antiretroviral agents.Coadministration of didanosine and stavudine is contraindicated because of increased risk of serious and/or life-threatening events. Suspend treatment if clinical or laboratory findings suggestive of lactic acidosis or pronounced hepatotoxicity occurs

Serious side effects of Videx

Along with its needed effects, didanosine (the active ingredient contained in Videx) may cause some unwanted effects. Although not all of these side effects may occur, if they do occur they may need medical attention.

Check with your doctor immediately if any of the following side effects occur while taking didanosine:

Less common

- Nausea

- stomach pain

- tingling, burning, numbness, and pain in the hands or feet

- vomiting

Rare

- Chills

- fever

- itching, skin rash

- seizures

- sore throat

- swelling of the feet or lower legs

- unusual bleeding and bruising

- unusual tiredness and weakness

- yellow skin and eyes

Incidence not known

- Anxiety

- black, tarry stools

- bleeding gums

- blindness

- bloating

- blood in the urine or stools

- blue-yellow color blindness

- blurred vision

- change in the color of the eye

- chest pain

- clay colored stools

- cold sweats

- confusion

- constipation

- cool, pale skin

- cough

- dark urine

- decreased appetite

- decreased vision

- depression

- diarrhea

- difficulty with moving

- difficulty with swallowing

- dizziness

- dry eyes or mouth

- eye pain

- fast heartbeat

- fast, shallow breathing

- flushed, dry skin

- fruit-like breath odor

- general feeling of discomfort

- headache

- hives

- increased hunger

- increased thirst

- increased urination

- indigestion

- joint pain

- light-colored stools

- loss of appetite

- loss of consciousness

- muscle aching, cramping, or pain

- nightmares

- painful or difficult urination

- pains in the stomach, side, or abdomen, possibly radiating to the back

- pinpoint red spots on the skin

- puffiness or swelling of the eyelids or around the eyes, face, lips, or tongue

- right upper abdominal or stomach pain and fullness

- shakiness

- sleepiness

- slurred speech

- sores, ulcers, or white spots on the lips or in the mouth

- stomach ache or discomfort

- sweating

- swollen glands or joints

- tightness in the chest

- troubled breathing with exertion

- unexplained weight loss

- unsteadiness or awkwardness

- weakness in the arms, hands, legs, or feet

Other side effects of Videx

Some side effects of didanosine may occur that usually do not need medical attention. These side effects may go away during treatment as your body adjusts to the medicine. Also, your health care professional may be able to tell you about ways to prevent or reduce some of these side effects.

Check with your health care professional if any of the following side effects continue or are bothersome or if you have any questions about them:

More common

- Difficulty with sleeping

- irritability

- restlessness

Incidence not known

- Belching

- excess air or gas in the stomach or bowels

- feeling of fullness

- hair loss or thinning of the hair

- heartburn

- indigestion

- lack or loss of strength

- passing gas

For Healthcare Professionals

Applies to didanosine: oral delayed release capsule, oral powder for reconstitution, oral tablet chewable.

General

The most common side effects were diarrhea, peripheral neurologic symptoms/neuropathy, abdominal pain, nausea, headache, rash, and vomiting. Significant toxicities included pancreatitis, lactic acidosis/severe hepatomegaly with steatosis, retinal changes, optical neuritis, and peripheral neuropathy.[Ref]

Gastrointestinal

In combination therapy trials, elevated amylase (grades 3 to 4: up to 8%; all grades: up to 31%) and lipase (grades 3 to 4: up to 7%; all grades: up to 26%) were reported; grades 3 to 4 amylase and lipase elevations were greater than 2 times the upper limit of normal (2 x ULN).

In monotherapy trials, elevated amylase (at least 1.4 x ULN) was reported in up to 17% of patients.

Pancreatitis resulting in death has been reported during clinical trials of this drug in combination with other antiretroviral agents. The frequency of pancreatitis was dose-related. In phase 3 trials with buffered formulations, incidence ranged from 1% to 10% with doses higher than currently recommended and 1% to 7% with recommended doses.[Ref]

Very common (10% or more): Diarrhea (up to 70%), nausea (up to 53%), elevated amylase (up to 31%), vomiting (up to 30%), elevated lipase (up to 26%), abdominal pain (up to 13%)

Common (1% to 10%): Pancreatitis

Postmarketing reports: Dyspepsia, flatulence, pancreatitis (including fatal cases), dry mouth, sialoadenitis, parotid gland enlargement, increased/abnormal serum amylase[Ref]

Hepatic

Very common (10% or more): Elevated bilirubin (up to 68%), elevated AST (up to 53%), elevated ALT (up to 50%), elevated GGT (up to 28%)

Frequency not reported: Severe hepatomegaly with steatosis, hepatic toxicity, fatal hepatic events, fulminant hepatitis (including fatal cases)

Postmarketing reports: Hepatic steatosis, noncirrhotic portal hypertension, hepatitis, liver failure[Ref]

In combination therapy trials, elevated AST (grades 3 to 4: up to 7%; all grades: up to 53%), ALT (grades 3 to 4: up to 8%; all grades: up to 50%), bilirubin (grades 3 to 4: up to 16%; all grades: up to 68%), and GGT (grades 3 to 4: up to 5%; all grades: up to 28%) were reported; grades 3 to 4 AST, ALT, and GGT elevations were greater than 5 x ULN and grades 3 to 4 bilirubin elevations were greater than 2.6 x ULN.

In monotherapy trials, elevated AST (greater than 5 x ULN) and ALT (greater than 5 x ULN) were each reported in up to 9% of patients.

Lactic acidosis and severe hepatomegaly with steatosis (including fatal cases) have been reported with the use of nucleoside analogs alone or in combination with other antiretrovirals.

Fatal hepatic events were reported most often in patients treated with this drug in combination with hydroxyurea and stavudine.[Ref]

Nervous system

Neuropathy presented as tingling, numbness, or pain in the hands or soles of the feet which progressed up the legs. The incidence was higher in patients with history of neuropathy and/or low CD4+ cell counts (less than 50 cells/mm3). Following discontinuation of this drug, neuropathy usually resolved within 2 to 12 weeks.[Ref]

Very common (10% or more): Headache (up to 46%), peripheral neurologic symptoms/neuropathy (up to 26%)

Frequency not reported: Seizures[Ref]

Dermatologic

Very common (10% or more): Rash (up to 30%)

Common (1% to 10%): Rash/pruritus

Frequency not reported: Lipoatrophy/subcutaneous fat loss, cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis

Postmarketing reports: Alopecia[Ref]

Subcutaneous fat loss was most apparent in the face, limbs, and buttocks. The incidence and severity of lipoatrophy have been linked to cumulative exposure. Often, lipoatrophy was not reversible when this drug was discontinued.[Ref]

Other

Common (1% to 10%): Fatigue

Uncommon (0.1% to 1%): Increased alkaline phosphatase

Frequency not reported: Edema

Postmarketing reports: Asthenia, chills/fever, pain, increased/abnormal alkaline phosphatase

Antiretroviral therapy:

-Frequency not reported: Increased weight, increased blood lipid levels[Ref]

In monotherapy trials, elevated alkaline phosphatase (greater than 5 x ULN) was reported in up to 4% of patients.[Ref]

Hematologic

Thrombocytopenia and splenomegaly have been reported as early signs of noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

Anemia and thrombocytopenia have also been reported during postmarketing experience.[Ref]

Common (1% to 10%): Neutropenia

Uncommon (0.1% to 1%): Anemia, thrombocytopenia

Frequency not reported: Splenomegaly

Postmarketing reports: Leukopenia, granulocytopenia[Ref]

Metabolic

In monotherapy trials, elevated uric acid (greater than 12 mg/dL) was reported in up to 3% of patients.

Hyperlactatemia appeared to be more common with this drug while lactic acidosis was an infrequent occurrence.

Lactic acidosis and severe hepatomegaly with steatosis (including fatal cases) have been reported with the use of nucleoside analogs alone or in combination with other antiretrovirals. Fatal lactic acidosis has been reported in pregnant women who received this drug plus stavudine with other antiretroviral agents.

In a report following patients on combined therapy with this drug and tenofovir, 1 patient developed didanosine-related toxicity characterized by lactic acidosis with liver failure after 3 months using 200 mg/day of this drug with tenofovir.

In 1 case report, acute gouty arthritis developed 14 weeks after this drug was added to the treatment regimen of a patient receiving ritonavir, both known to infrequently cause hyperuricemia. The symptoms resolved upon discontinuation of this drug and a short course of indomethacin.[Ref]

Common (1% to 10%): Elevated serum uric acid

Frequency not reported: Hyperuricemia, hypertriglyceridemia, impaired glucose tolerance, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, acute gouty arthritis

Postmarketing reports: Anorexia, symptomatic hyperlactatemia/lactic acidosis, diabetes mellitus, hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia

Antiretroviral therapy:

-Frequency not reported: Increased glucose levels[Ref]

Psychiatric

Frequency not reported: Insomnia, restlessness

Ocular

Frequency not reported: Retinal changes, optic neuritis, diffuse dysfunction of the retinal epithelium with bilateral visual deficit (including night blindness and a peripheral visual fold reduction)

Postmarketing reports: Dry eyes, retinal depigmentation[Ref]

Diffuse dysfunction of the retinal epithelium has been reported in 2 patients during therapy with this drug. Both patients experienced bilateral visual deficit including night blindness and a peripheral visual fold reduction. Symptoms were first noted after 31 and 34 weeks of therapy. Deficits in both patients appeared to be partially reversible upon discontinuation of this drug.

Optic neuritis has also been reported during postmarketing experience.[Ref]

Musculoskeletal

Frequency not reported: Osteonecrosis

Postmarketing reports: Myalgia (with or without increased creatine phosphokinase), rhabdomyolysis (including acute renal failure and hemodialysis), arthralgia, myopathy, increased/abnormal creatine phosphokinase[Ref]

Hypersensitivity

Postmarketing reports: Anaphylactoid/anaphylactic reaction[Ref]

Immunologic

Frequency not reported: Immune reconstitution/reactivation syndrome, autoimmune disorders in the setting of immune reconstitution (e.g., Graves' disease, polymyositis, Guillain-Barre syndrome)

Endocrine

Postmarketing reports: Gynecomastia[Ref]

Respiratory

Frequency not reported: Dyspnea, orthopnea

Cardiovascular

Frequency not reported: Cardiomyopathy aggravated, pericarditis, left ventricular failure[Ref]

Underlying cardiomyopathy may have been aggravated by treatment with buffered formulations, which had high sodium content.[Ref]

More about Videx (didanosine)

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

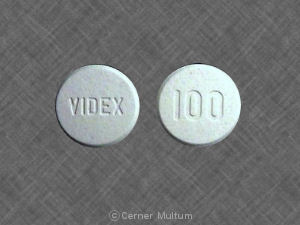

- Drug images

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs)

- Breastfeeding

Patient resources

Other brands

Professional resources

Other brands

Related treatment guides

References

1. Shelton MJ, O'Donnell AM, Morse GD. Didanosine. Ann Pharmacother. 1992;26:660-70.

2. Yarchoan R, Mitsuya H, Pluda JM, et al. The National Cancer Institute phase I study of 2',3'-dideoxyinosine administration in adults with AIDS-related complex: analysis of activity and toxicity profiles. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:s522-33.

3. Schindzielorz A, Pike I, Daniels M, Pacelli L, Smaldone L. Rates and risk factors for adverse events associated with didanosine in the expanded access program. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:1076-83.

4. Brinkman K, terHofstede HJM, Burger DM, Smeitinkt JAM, Koopmans PP. Adverse effects of reverse transcriptase inhibitors: mitochondrial toxicity as common pathway. AIDS. 1998;12:1735-44.

5. Product Information. Videx EC (didanosine). Bristol-Myers Squibb. 2001;PROD.

6. Drugs for HIV infection. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2001;43:103-8.

7. Walker UA, Bauerle J, Laguno M, et al. Depletion of mitochondrial DNA in liver under antiretroviral therapy with didanosine, stavudine, or zalcitabine. Hepatology. 2004;39:311-7.

8. Kakuda TN. Pharmacology of nucleoside and nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor-induced mitochondrial toxicity. Clin Ther. 2000;22:685-708.

9. Anderson PL. Pharmacologic perspectives for once-daily antiretroviral therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:1969-70.

10. Neff GW, Sherman KE, Eghtesad B, Fung J. Review article: current status of liver transplantation in HIV-infected patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:993-1000.

11. Piacenti FJ. An update and review of antiretroviral therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:1111-33.

12. Gallant JE. Drug resistance after failure of initial antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited countries. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:453-5.

13. Bolhaar MG, Karstaedt AS. A high incidence of lactic acidosis and symptomatic hyperlactatemia in women receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy in Soweto, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:254-60.

14. Moreno S, Hernandez B, Dronda F. Didanosine Enteric-Coated Capsule : Current Role in Patients with HIV-1 Infection. Drugs. 2007;67:1441-62.

15. Risk factors for lactic acidosis and severe hyperlactataemia in HIV-1-infected adults exposed to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2007;21:2455-64.

16. Warnke D, Barreto J, Temesgen Z. Antiretroviral drugs. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47:1570-9.

17. Thoden J, Lebrecht D, Venhoff N, Neumann J, Muller K, Walker UA. Highly active antiretroviral HIV therapy-associated fatal lactic acidosis: quantitative and qualitative mitochondrial DNA lesions with mitochondrial dysfunction in multiple organs. AIDS. 2008;22:1093-4.

18. Drugs for HIV infection. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2009;7:11-22.

19. Dolin R, Lambert JS, Morse GD, et al. 2',3'-dideoxyinosine in patients with AIDS or AIDS-related complex. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:s540-51.

20. Rozencweig M, Mclaren C, Beltangady M, et al. Overview of phase I trials of 2',3'-dideoxyinosine (ddI) conducted on adult patients. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:s570-5.

21. Bouvet E, Casalino E, Prevost MH, Vachon F. Fatal case of 2',3'-dideoxyinosine-associated pancreatitis. Lancet. 1990;336:1515.

22. Connolly KJ, Allan JD, Fitch H, et al. Phase I study of 2'-3'-didwoxyinosine administered orally twice daily to patients with AIDS or AIDS-related complex and hematologic intolerance to zidovudine. Am J Med. 1991;91:471-8.

23. Maxson CJ, Greenfield SM, Turner JL. Acute pancreatitis as a common complication of 2',3'-dideoxyinosine therapy in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:708-13.

24. Faulds D, Brogden RN. Didanosine: a review of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic potential in human innumodeficiency virus infection. Drugs. 1992;44:94-116.

25. Pike IM, Nicaise C. The didanosine Expanded Access Program: safety analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:S63-8.

26. Grasela TH, Walawander CA, Beltangady M, Knupp CA, Martin RR, Dunkle LM, Barbhaiya RH, Pittman KA, Dolin R, Valentine FT,. Analysis of potential risk factors associated with the development of pancreatitis in phase i patients with AIDS or AIDS-related complex receiving didanosine. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1250-5.

27. Montaner JSG, Rachlis A, Beaulieu R, Gill J, Schlech W, Phillips P, Auclair C, Boulerice F, Schindzielorz A, Smaldone L, Wainber. Safety profile of didanosine among patients with advanced HIV disease who are intolerant to or deteriorate despite zidovudine therapy: results of the canadian open ddi treatment program. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:924-30.

28. Moore RD, Fortgang I, Keruly J, Chaisson RE. Adverse events from drug therapy for human immunodeficiency virus disease. Am J Med. 1996;101:34-40.

29. Dassopoulos T, Ehrenpreis ED. Acute pancreatitis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: A review. Am J Med. 1999;107:78-84.

30. Perry CM, Noble S. Didanosine - An updated review of its use in HIV infection. Drugs. 1999;58:1099-135.

31. Pollard RB. Didanosine once daily: potential for expanded use. Aids. 2000;14:2421-8.

32. Callens S, De Schacht C, Huyst V, Colebunders R. Pancreatitis in an HIV-infected person on a tenofovir, didanosine and stavudine containing highly active antiretroviral treatment. J Infect. 2003;47:188-9.

33. Guo JJ, Jang R, Louder A, Cluxton RJ. Acute pancreatitis associated with different combination therapies in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:1044-54.

34. Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in pediatric HIV infection. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/pediatricguidelines.pdf 2017.

35. DHHS Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents – A Working Group of the Office of AIDS Research Advisory Council (OARAC). Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf 2017.

36. Lai KK, Gang DL, Zawacki JK, Cooley TP. Fulminant hepatic failure associated with 2',3'-dideoxyinosine (ddI). Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:283-4.

37. Product Information. Videx (didanosine). Bristol-Myers Squibb. 2002;PROD.

38. Ware AJ, Berggren RA, Taylor WE. Didanosine-induced hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2141-3.

39. Moyle GJ, Datta D, Mandalia S, Morlese J, Asboe D, Gazzard BG. Hyperlactataemia and lactic acidosis during antiretroviral therapy: relevance, reproducibility and possible risk factors. AIDS. 2002;16:1341-1349.

40. Bonnet F, Bonarek M, Morlat P, et al. Risk factors for lactic acidosis in HIV-infected patients treated with nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors: a case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1324-8.

41. Masia M, Gutierrez F, Padilla S, Ramos JM, Pascual J. Didanosine-associated toxicity: a predictable complication of therapy with tenofovir and didanosine? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35:427-8.

42. Soriano V, Puoti M, Sulkowski M, et al. Care of patients coinfected with HIV and hepatitis C virus: 2007 updated recommendations from the HCV-HIV International Panel. AIDS. 2007;21:1073-89.

43. Kelleher T, Cross A, Dunkle L. Relation of peripheral neuropathy to HIV treatment in four randomized clinical trials including didanosine. Clin Ther. 1999;21:1182-92.

44. Herranz P, Fernandezdiaz ML, Delucas R, Gonzalezgarcia J, Casado M. Cutaneous vasculitis associated with didanosine. Lancet. 1994;344:680.

45. Domingo P, Barcelo M. Efavirenz-induced leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:355-6.

46. Martinez E, Mocroft A, GarciaViejo MA, PerezCuevas JB, Blanco JL, Mallolas J, Bianchi L, Conget I, Blanch J, Phillips A, Gatell. Risk of lipodystrophy in HIV-1-infected patients treated with protease inhibitors: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2001;357:592-8.

47. Lor E, Liu YQ. Didanosine-associated eosinophilia with acute thrombocytopenia. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27:23-5.

48. Mehlhaff DL, Stein DS. Gout secondary to ritonavir and didanosine. AIDS. 1996;10:1744.

49. Lafeuillade A, Aubert L, Chaffanjon P, Quilichini R. Optic neuritis associated with dideoxyinosine. Lancet. 1991;337:615-6.

50. Cobo J, Ruiz MF, Figueroa MS, Antela A, Quereda C, Perezelias MJ, Corral I, Guerrero A. Retinal toxicity associated with didanosine in HIV-infected adults. AIDS. 1996;10:1297-300.

51. Tal A, Dall L. Didanosine-induced hypertriglyceridemia. Am J Med. 1993;95:247.

52. Albrecht H, Stellbrink HJ, Arasteh K. Didanosine-induced disorders of glucose tolerance. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:1050.

53. Vittecoq D, Zucman D, Auperin I, Passeron J. Transient insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in an HIV-infected patient receiving didanosine. AIDS. 1994;8:1351.

54. Dube MP. Disorders of glucose metabolism in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:1467-75.

55. Willocks L, Brettle R, Keen J. Formulation of didanosine (ddI) and salt overload. Lancet. 1992;339:190.

Further information

Always consult your healthcare provider to ensure the information displayed on this page applies to your personal circumstances.

Some side effects may not be reported. You may report them to the FDA.