Ketorolac (Monograph)

Brand name: Sprix

Drug class: Other Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents

VA class: CN103

Chemical name: (±)-5-Benzoyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrrolizine-1-carboxylic acid compd. with 2-Amino-2-(hydroxymethyl)-1,3-propanediol (1:1)

Molecular formula: C15H13O3•C4H11NO3

CAS number: 74103-07-4

Warning

- Appropriate Use

-

Parenteral and oral ketorolac indicated for short-term (≤5 days) management of moderately severe acute pain that requires analgesia at opiate level.207 1201 Oral ketorolac indicated only for continuation therapy and only if necessary; do not exceed 5 days of total parenteral and oral therapy.207 1201 Not indicated for pediatric use or for use in minor or chronic painful conditions.207 1201

-

Increasing the dose beyond the recommended dose will not result in improved efficacy and increases the risk of serious adverse effects.1

- GI Effects

-

Can cause peptic ulcers, GI bleeding, and/or perforation,.1 Contraindicated in patients with active peptic ulcer disease, recent GI bleeding or perforation, or a history of peptic ulcer disease or GI bleeding.1

-

Serious GI events can be fatal and can occur at any time and may not be preceded by warning signs and symptoms.198 207 1201 Geriatric individuals and patients with history of peptic ulcer disease and/or GI bleeding are at greater risk for serious GI events.198 208 (See GI Effects under Cautions.)

- Cardiovascular Risk

-

Increased risk of serious (sometimes fatal) cardiovascular thrombotic events (e.g., MI, stroke).198 502 508 Risk may occur early in treatment and may increase with duration of use.500 502 505 506 508 (See Cardiovascular Thrombotic Effects under Cautions.)

-

Contraindicated in the setting of CABG surgery.508

- Renal Effects

-

Contraindicated in patients with advanced renal impairment and those at risk of renal failure because of volume depletion.1

- Hematologic Effects

-

Inhibits platelet function.1 Contraindicated in patients with suspected or confirmed cerebrovascular bleeding, hemorrhagic diathesis, or incomplete hemostasis and in patients at a high risk of bleeding.1

-

Contraindicated as prophylactic analgesic before major surgery.207 1201

- Sensitivity Reactions

-

Hypersensitivity reactions (e.g., bronchospasm, anaphylactic shock) reported; appropriate counteractive measures must be available when administering the first dose.1201 Contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to ketorolac, aspirin, or other NSAIAs.1201

- Intrathecal or Epidural Administration

-

Contraindicated for intrathecal or epidural administration because of alcohol content in parenteral formulation.1

- Labor and Delivery

-

Contraindicated during labor and delivery.207 1201 (See Pregnancy under Cautions.)

Introduction

Prototypical NSAIA;1 2 3 21 32 33 70 91 92 93 96 140 pyrrolizine carboxylic acid derivative;2 3 21 32 33 70 91 92 93 96 140 structurally related to tolmetin and indomethacin.2 33 47 70 83

Uses for Ketorolac

Pain

Consider potential benefits and risks of ketorolac therapy as well as alternative therapies before initiating therapy with the drug.198 Use lowest effective dosage and shortest duration of therapy consistent with the patient’s treatment goals.198

Parenteral ketorolac or sequential parenteral and oral ketorolac: Short-term (i.e., up to 5 days) management of moderately severe, acute pain that requires analgesia at opiate level; mainly used in the postoperative setting.1 47 48 49 50 51 52 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 68 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 91 99 101 159 161 162 165 196 197 207 1201

Intranasal ketorolac: Short-term (i.e., up to 5 days) management of moderate to moderately severe pain that requires analgesia at the opiate level.208

Parenteral ketorolac has been used concomitantly with opiate agonist analgesics (e.g., meperidine, morphine) for the management of moderate to severe postoperative pain without apparent adverse drug interactions.1 91 Combined use can result in reduced opiate analgesic requirements.1 49 (See Syringe Compatibility under Stability.)

Ketorolac Dosage and Administration

General

-

Current principles of pain management indicate that analgesics, including ketorolac, should be administered at regularly scheduled intervals, although the drug also has been administered on an as-needed basis (i.e., withholding subsequent doses until pain returns).1 91 140

-

Consider potential benefits and risks of ketorolac therapy as well as alternative therapies before initiating therapy with the drug.198

Administration

Administer by IM or IV injection,1 23 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 154 156 161 162 163 164 165 orally,1 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 or intranasally.208

Switch patients to alternate analgesic therapy as soon as clinically possible.1 154

Oral Administration

Oral formulation is used as continuation therapy only if required following initial parenteral (IV or IM) ketorolac.1 154

Manufacturer makes no specific recommendations regarding administration with meals; high-fat meal may decrease rate but not extent of absorption and reduce peak plasma concentrations.1

IV Administration

For solution and drug compatibility information, see Compatibility under Stability.

Rate of Administration

Administer over ≥15 seconds.1

IM Administration

Administer IM slowly and deeply into the muscle.1

For drug compatibility information, see Compatibility under Stability.

Intranasal Administration

Administer nasal solution using a metered-dose spray pump.208 Prime pump prior to initial use.208 Consult manufacturer's instructions for use of the nasal spray pump.208

Not an inhalation product; therefore, patient should not inhale during administration.208

Avoid contact with the eyes; if contact occurs, rinse affected eye(s) with water or saline.208 Patient should consult clinician if ocular irritation persists for >1 hour.208

Use each bottle of nasal solution for only 24 hours and then discard; manufacturer states that spray pump will not deliver the intended dose after 24 hours.208

Dosage

Available as ketorolac tromethamine; dosage expressed in terms of the salt.1

Nasal spray pump delivers 15.75 mg of ketorolac tromethamine per 100-µL metered spray and 8 sprays per single-day bottle.208

To minimize the potential risk of adverse cardiovascular and/or GI events, use lowest effective dosage and shortest duration of therapy consistent with the patient’s treatment goals.198 Adjust dosage based on individual requirements and response; attempt to titrate to the lowest effective dosage.198

For breakthrough pain, supplement with low doses of opiate analgesics (unless contraindicated) as needed rather than higher or more frequent doses of ketorolac.1 142

Adults

Pain

Oral

Adults 17–64 years of age: When switching from parenteral to oral therapy, the first oral dose is 20 mg, followed by 10 mg every 4–6 hours as needed (maximum 40 mg in a 24-hour period).1 207

Weight <50 kg: When switching from parenteral to oral therapy, 10 mg every 4–6 hours as needed (maximum 40 mg in a 24-hour period).1 207

IV

30 mg for single-dose therapy.1201 For multiple-dose therapy, 30 mg every 6 hours.1201

Weight <50 kg: 15 mg for single-dose therapy.1201 For multiple-dose therapy, 15 mg every 6 hours.1201

IM

60 mg for single-dose therapy.1201 For multiple-dose therapy, 30 mg every 6 hours.1201

Weight <50 kg: 30 mg for single-dose therapy.1201 For multiple-dose therapy, 15 mg every 6 hours.1201

Intranasal

31.5 mg (one spray in each nostril) every 6–8 hours (maximum 126 mg [4 doses] daily).208

Weight <50 kg: 15.75 mg (one spray in only one nostril) every 6–8 hours (maximum 63 mg [4 doses] daily).208

Prescribing Limits

Adults

Pain

Total duration of ketorolac therapy (including parenteral, oral, and intranasal therapy) should not exceed 5 days.1 137 142 143 154 208

Oral

All adults: Maximum 40 mg in a 24-hour period.1

Administer doses no more frequently than every 4–6 hours.207

IV or IM

Maximum 120 mg in a 24-hour period.1

Weight <50 kg: Maximum 60 mg in a 24-hour period.1

Intranasal

Maximum 126 mg (4 doses) daily.208

Weight <50 kg: Maximum 63 mg (4 doses) daily.208

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

Evidence in patients with cirrhosis suggests that dosage adjustment may not be necessary.137

Renal Impairment

Pain

Contraindicated in patients with advanced renal disease.207 208 1201 Use reduced dosage in those with moderately increased Scr.207 208 1201

Oral

When switching from parenteral to oral therapy, 10 mg every 4–6 hours as needed (maximum 40 mg in a 24-hour period).207

IV

15 mg for single-dose therapy.1201 For multiple-dose therapy, 15 mg every 6 hours (maximum 60 mg in a 24-hour period).1201

IM

30 mg for single-dose therapy.1 For multiple-dose therapy, 15 mg every 6 hours (maximum 60 mg in a 24-hour period).1201

Intranasal

15.75 mg (one spray in only one nostril) every 6–8 hours (maximum 63 mg [4 doses] daily).208

Geriatric Patients

Adults ≥65 years of age: Use dosage recommended for adults weighing <50 kg and those with moderately increased Scr.207 208 1201

Cautions for Ketorolac

Contraindications

-

Peptic ulcer disease, recent GI bleeding or perforation, or history of peptic ulcer disease or GI bleeding.1

-

Advanced renal impairment or risk of renal failure secondary to volume depletion.1

-

Known hypersensitivity (e.g., anaphylaxis, serious dermatologic reactions) to ketorolac or any ingredient in the formulation.198 208 1201

-

History of asthma, urticaria, or other sensitivity reactions precipitated by aspirin or other NSAIAs.1

-

In the setting of CABG surgery.1201

-

Suspected or confirmed cerebrovascular bleeding, hemorrhagic diathesis, or incomplete hemostasis; high risk of bleeding.1

-

Neuraxial (epidural or intrathecal) administration.1

-

Concomitant use with probenecid or pentoxifylline.1201

-

Manufacturers of oral and parenteral ketorolac also state the drug is contraindicated in patients receiving concomitant aspirin or NSAIA therapy.207 1201

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Duration of Therapy

Total duration of therapy (including parenteral, oral, and intranasal formulations) should not exceed 5 days.1 137 142 143 154 208

Cardiovascular Thrombotic Effects

NSAIAs (selective COX-2 inhibitors, prototypical NSAIAs) increase the risk of serious adverse cardiovascular thrombotic events (e.g., MI, stroke) in patients with or without cardiovascular disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease.500 502 508

Findings of FDA review of observational studies, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, and other published information500 501 502 indicate that NSAIAs may increase the risk of such events by 10–50% or more, depending on the drugs and dosages studied.500

Relative increase in risk appears to be similar in patients with or without known underlying cardiovascular disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease, but the absolute incidence of serious NSAIA-associated cardiovascular thrombotic events is higher in those with cardiovascular disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease because of their elevated baseline risk.500 502 506 508

Increased risk may occur early (within the first weeks) following initiation of therapy and may increase with higher dosages and longer durations of use.500 502 505 506 508

In controlled studies, increased risk of MI and stroke observed in patients receiving a selective COX-2 inhibitor for analgesia in first 10–14 days following CABG surgery.508

In patients receiving NSAIAs following MI, increased risk of reinfarction and death observed beginning in the first week of treatment.505 508

Increased 1-year mortality rate observed in patients receiving NSAIAs following MI;500 508 511 absolute mortality rate declined somewhat after the first post-MI year, but the increased relative risk of death persisted over at least the next 4 years.508 511

Some systematic reviews of controlled observational studies and meta-analyses of randomized studies suggest naproxen may be associated with lower risk of cardiovascular thrombotic events compared with other NSAIAs.202 203 204 206 500 501 502 503 506 FDA states that limitations of these studies and indirect comparisons preclude definitive conclusions regarding relative risks of NSAIAs.500

Use NSAIAs with caution and careful monitoring (e.g., monitor for development of cardiovascular events throughout therapy, even in those without prior cardiovascular symptoms) and at the lowest effective dosage for the shortest duration necessary.198 500 508

Some clinicians suggest that it may be prudent to avoid NSAIA use, whenever possible, in patients with cardiovascular disease.505 511 512 516 Avoid use in patients with recent MI unless benefits of therapy are expected to outweigh risk of recurrent cardiovascular thrombotic events; if used, monitor for cardiac ischemia.508 Contraindicated in the setting of CABG surgery.508

No consistent evidence that concomitant use of low-dose aspirin mitigates the increased risk of serious adverse cardiovascular events associated with NSAIAs.198 502 508 (See Specific Drugs under Interactions.)

GI Effects

Serious, sometimes fatal, GI toxicity (e.g., bleeding, ulceration, or perforation of esophagus, stomach, or small or large intestine) can occur with or without warning symptoms.1 124 125 141 198 208

Risk for GI bleeding increased greater than tenfold in patients with a history of peptic ulcer disease and/or GI bleeding who are receiving NSAIAs compared with patients without these risk factors.192 193 208

Other risk factors for GI bleeding include concomitant use of oral corticosteroids, aspirin, anticoagulants, or SSRIs; longer duration of NSAIA therapy; smoking; alcohol use; older age; poor general health status; and advanced liver disease and/or coagulopathy.192 193 195 208 (See Contraindications under Cautions.)

Geriatric or debilitated patients appear to tolerate ulceration and bleeding less well than other individuals; most spontaneous reports of fatal GI effects involve such patients.1 122 125 126 127 141

Use at lowest effective dosage for the shortest duration necessary.198 Avoid use of more than one NSAIA at a time.208 (See Specific Drugs under Interactions.)

Avoid use of NSAIAs in patients at higher risk for GI toxicity unless expected benefits outweigh increased risk of bleeding; consider alternate therapies.208

NSAIAs may exacerbate inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease); use with great caution in patients with a history of such disease.208

Hematologic Effects

May inhibit platelet aggregation and prolong bleeding time.1 2 23 24 34 65 70 91 141 Use with caution and careful monitoring in patients with coagulation disorders.1 (See Contraindications under Cautions.)

Hematomas and other signs of wound bleeding reported in patients receiving the drug perioperatively; undertake postoperative administration with caution when hemostasis is critical.1 (See Contraindications under Cautions.)

Increased risk of intramuscular hematoma following IM administration in patients receiving anticoagulants.1 154

Administer with caution in patients receiving therapeutic doses of anticoagulants (e.g., heparin, warfarin).1 154 Concurrent use with prophylactic low-dose heparin (2500–5000 units every 12 hours), warfarin, or dextrans not studied extensively, but also may be associated with increased risk of bleeding.1 154 Administer with caution when the potential benefits justify the possible risks.1 91 145 154 (See Specific Drugs under Interactions.)

Increased risk of bleeding following tonsillectomy in pediatric patients.1 174 196 197

Renal Effects

Direct renal injury, including renal papillary necrosis, reported in patients receiving long-term NSAIA therapy.1 154 Interstitial nephritis and nephrotic syndrome reported in patients receiving ketorolac.1

Potential for overt renal decompensation.1 154 Increased risk of renal toxicity in patients with renal or hepatic impairment or heart failure; in patients with volume depletion; in geriatric patients; and in those receiving a diuretic, ACE inhibitor, or angiotensin II receptor antagonist.1 91 147 154 201 205 (See Renal Impairment and also Contraindications under Cautions, and Renal Impairment under Dosage and Administration.)

Correct hypovolemia before initiating ketorolac therapy.1

Other Warnings and Precautions

Hypertension

Hypertension and worsening of preexisting hypertension reported;1 91 198 either event may contribute to the increased incidence of cardiovascular events.198 Monitor BP.198

Impaired response to ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, β-blockers, and certain diuretics may occur.198 508 509 (See Specific Drugs under Interactions.)

Heart Failure and Edema

Fluid retention and edema reported.1 70 91 140 508

NSAIAs (selective COX-2 inhibitors, prototypical NSAIAs) may increase morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure.500 501 504 507 508

NSAIAs may diminish cardiovascular effects of diuretics, ACE inhibitors, or angiotensin II receptor antagonists used to treat heart failure or edema.508 (See Specific Drugs under Interactions.)

Manufacturer recommends avoiding use in patients with severe heart failure unless benefits of therapy are expected to outweigh risk of worsening heart failure; if used, monitor for worsening heart failure.508

Some experts recommend avoiding use, whenever possible, in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction and current or prior symptoms of heart failure.507

Hypersensitivity Reactions

Anaphylactoid reactions (e.g., anaphylaxis, angioedema) reported.1 Immediate medical intervention and discontinuance for anaphylaxis.1

Avoid in patients with aspirin triad (aspirin sensitivity, asthma, nasal polyps); caution in patients with asthma.1 2

Potentially fatal or life-threatening syndrome of multi-organ hypersensitivity (i.e., drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms [DRESS]) reported in patients receiving NSAIAs.1201 Clinical presentation is variable, but typically includes eosinophilia, fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, and/or facial swelling, possibly associated with other organ system involvement (e.g., hepatitis, nephritis, hematologic abnormalities, myocarditis, myositis).1201 Symptoms may resemble those of acute viral infection.1201 Early manifestations of hypersensitivity (e.g., fever, lymphadenopathy) may be present in the absence of rash.1201 If signs or symptoms of DRESS develop, discontinue ketorolac and immediately evaluate the patient.1201

Dermatologic Reactions

Serious skin reactions (e.g., exfoliative dermatitis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis) reported; can occur without warning.1 91 198 Discontinue at first appearance of rash or any other sign of hypersensitivity (e.g., blisters, fever, pruritus).198

Hepatic Effects

Severe reactions including jaundice, fatal fulminant hepatitis, liver necrosis, and hepatic failure (sometimes fatal) reported rarely with NSAIAs.1 198

Elevations in ALT or AST reported.1 91

Monitor for symptoms and/or signs suggesting liver dysfunction; monitor abnormal liver function test results.198 Discontinue ketorolac if associated with abnormal liver function test results.1

Other Precautions

Not a substitute for corticosteroid therapy; not effective in the management of adrenal insufficiency.1201

May mask certain signs of infection or other disease.138

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Use of NSAIAs during pregnancy at about ≥30 weeks’ gestation can cause premature closure of the fetal ductus arteriosus; use at about ≥20 weeks’ gestation associated with fetal renal dysfunction resulting in oligohydramnios and, in some cases, neonatal renal impairment.1200 1201

Effects of NSAIAs on the human fetus during third trimester of pregnancy include prenatal constriction of the ductus arteriosus, tricuspid incompetence, and pulmonary hypertension; nonclosure of the ductus arteriosus during the postnatal period (which may be resistant to medical management); and myocardial degenerative changes, platelet dysfunction with resultant bleeding, intracranial bleeding, renal dysfunction or renal failure, renal injury or dysgenesis potentially resulting in prolonged or permanent renal failure, oligohydramnios, GI bleeding or perforation, and increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis.1202

Avoid use of NSAIAs in pregnant women at about ≥30 weeks’ gestation; if use required between about 20 and 30 weeks’ gestation, use lowest effective dosage and shortest possible duration of treatment, and consider monitoring amniotic fluid volume via ultrasound examination if treatment duration >48 hours; if oligohydramnios occurs, discontinue drug and follow up according to clinical practice.1200 1201 (See Advice to Patients.)

Fetal renal dysfunction resulting in oligohydramnios and, in some cases, neonatal renal impairment observed, on average, following days to weeks of maternal NSAIA use; infrequently, oligohydramnios observed as early as 48 hours after initiation of NSAIAs.1200 1201 Oligohydramnios is often, but not always, reversible (generally within 3–6 days) following NSAIA discontinuance.1200 1201 Complications of prolonged oligohydramnios may include limb contracture and delayed lung maturation.1200 1201 In limited number of cases, neonatal renal dysfunction (sometimes irreversible) occurred without oligohydramnios.1200 1201 Some neonates have required invasive procedures (e.g., exchange transfusion, dialysis).1200 1201 Deaths associated with neonatal renal failure also reported.1200 Limitations of available data (lack of control group; limited information regarding dosage, duration, and timing of drug exposure; concomitant use of other drugs) preclude a reliable estimate of the risk of adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes with maternal NSAIA use.1201 Available data on neonatal outcomes generally involved preterm infants; extent to which risks can be generalized to full-term infants is uncertain.1201

Animal data indicate important roles for prostaglandins in kidney development and endometrial vascular permeability, blastocyst implantation, and decidualization.1201 In animal studies, inhibitors of prostaglandin synthesis increased pre- and post-implantation losses; also impaired kidney development at clinically relevant doses.1201

In animal studies, ketorolac delayed parturition and increased incidence of dystocia.1 91 Animal studies conducted during organogenesis revealed no evidence of fetal harm.1 91 92

Ketorolac may adversely affect fetal circulation and inhibit uterine contractions during labor and delivery, increasing risk of uterine hemorrhage.1 (See Contraindications under Cautions.)

Lactation

May be distributed into milk in small amounts.208

Consider developmental and health benefits of breast-feeding along with the mother's clinical need for ketorolac and any potential adverse effects on the breast-fed infant from the drug or underlying maternal condition.208

Although no specific adverse events reported in nursing infants, exercise caution and advise women to contact their infant's clinician if they observe any adverse events.208

Fertility

NSAIAs may be associated with reversible infertility in some women.208 Reversible delays in ovulation observed in limited studies in women receiving NSAIAs; animal studies indicate that inhibitors of prostaglandin synthesis can disrupt prostaglandin-mediated follicular rupture required for ovulation.208

Consider withdrawal of NSAIAs in women experiencing difficulty conceiving or undergoing evaluation of infertility.208 1201

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy of ketorolac (oral, parenteral, or intranasal) not established in pediatric patients <17 years of age.207 208 1201 Manufacturer states ketorolac nasal spray should not be used in pediatric patients <2 years of age.208

Meta-analysis of data from 13 randomized controlled trials that compared postoperative analgesic efficacy of ketorolac (any dosage and any route of administration) with that of placebo or another active treatment following any type of surgery in pediatric patients up to 18 years of age indicated that available data were inadequate to determine efficacy or assess safety in this population.211

Bleeding reported following tonsillectomy.1 174 196 197 (See Hematologic Effects under Cautions.)

Geriatric Use

Increased risk for serious adverse cardiovascular, GI, and renal effects.208 Fatal adverse GI effects reported more frequently in geriatric patients than younger adults.1 Incidence and severity of GI complications increase with increasing dose and duration of therapy.1 154

Substantially excreted by the kidneys; risk of adverse effects may be greater in patients with impaired renal function; because geriatric patients are more likely to have decreased renal function, consider monitoring renal function.208

Extreme caution and careful clinical monitoring advised.154 171 1201 If anticipated benefits outweigh potential risks, initiate ketorolac at lower end of dosing range;154 208 1201 adjust dose and frequency of administration based on response to initial therapy.208 (See Geriatric Patients under Dosage and Administration.)

Hepatic Impairment

Severe hepatic reactions possible.1 Use with caution in patients with hepatic impairment or a history of liver disease.1 91 92 154 (See Hepatic Impairment under Dosage and Administration.)

Renal Impairment

Use with caution in patients with renal impairment or a history of kidney disease since ketorolac is a potent inhibitor of prostaglandin synthesis and the drug and its metabolites are excreted principally by the kidneys; monitor closely.1 91 92 154 1201 (See Contraindications under Cautions.)

Clearance may be decreased.1 Dosage adjustment necessary in patients with moderately elevated Scr.1 (See Renal Impairment under Dosage and Administration.)

Patients with underlying renal insufficiency are at risk of developing acute renal failure; consider risks and benefits before instituting therapy in these patients.1 154

Common Adverse Effects

Oral or parenteral: Headache,1 23 70 91 34 somnolence or drowsiness,1 23 47 50 51 53 61 70 91 134 140 dizziness,1 23 50 53 70 91 dyspepsia,1 50 70 91 140 nausea,1 23 47 50 51 53 70 91 134 140 GI pain, 1 53 140 diarrhea,1 91 140 edema.1

Intranasal: Nasal discomfort, rhinalgia, increased lacrimation, throat irritation, oliguria, rash, bradycardia, decreased urine output, increased ALT and/or AST concentration, hypertension, rhinitis.208

Drug Interactions

Does not induce or inhibit hepatic enzymes involved in drug metabolism; unlikely to alter its own metabolism of that or other drugs metabolized by CYP isoenzymes.1

Protein-bound Drugs

Could be displaced from binding sites by, or could displace from binding sites, some other protein-bound drugs.1 91

Drugs Affecting Hemostasis

Possible increased risk of bleeding complications;1 carefully monitor patients receiving therapy that affects hemostasis.1 91 145 154

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

ACE inhibitors |

Reduced BP response to ACE inhibitor198 207 208 Possible reversible deterioration of renal function, including acute renal failure, in geriatric patients or patients with volume depletion or renal impairment208 |

Ensure adequate hydration; assess renal function when initiating concomitant therapy and periodically thereafter208 Monitor geriatric patients and patients with volume depletion or renal impairment for worsening renal function208 |

|

Acetaminophen |

||

|

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists |

Reduced BP response to angiotensin II receptor antagonist205 207 208 Possible reversible deterioration of renal function, including acute renal failure, in geriatric patients or patients with volume depletion or renal impairment205 208 |

Ensure adequate hydration; assess renal function when initiating concomitant therapy and periodically thereafter208 Monitor geriatric patients and patients with volume depletion or renal impairment for worsening renal function208 |

|

Antacids |

No effect on the extent of oral ketorolac absorption1 |

|

|

Anticonvulsants |

Seizures reported in patients receiving carbamazepine or phenytoin1 Phenytoin does not alter the protein binding of ketorolac1 91 |

|

|

β-Adrenergic blocking agents |

Monitor BP208 |

|

|

Cyclosporine |

Possible increased cyclosporine-associated nephrotoxicity208 |

Monitor for worsening renal function208 |

|

Dextrans |

Possible increased risk of bleeding1 |

|

|

Digoxin |

Increased digoxin serum concentrations and prolonged half-life reported208 |

Monitor serum digoxin concentrations208 |

|

Diuretics (furosemide, thiazides) |

Reduced natriuretic effect1 104 198 Possible increased risk of renal failure due to decreased renal blood flow resulting from prostaglandin inhibition1 |

Monitor for worsening renal function and for adequacy of diuretic and antihypertensive effects208 |

|

Fluticasone, intranasal |

Intranasal ketorolac: No change in rate or extent of ketorolac absorption in individuals with symptomatic allergic rhinitis208 |

|

|

Heparin |

Increased risk of bleeding complications1 Increased bleeding time when administered with heparin 5000 units; concurrent use with heparin 2500–5000 units sub-Q every 12 hours not studied extensively1 |

Extreme caution advised in patients receiving therapeutic doses of heparin;1 91 145 154 carefully monitor patients1 91 145 154 |

|

Lithium |

||

|

Methotrexate |

Increased plasma methotrexate concentrations in patients receiving other NSAIAs; studies with ketorolac have not been undertaken1 |

Monitor for methotrexate toxicity (e.g., neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, renal dysfunction)208 |

|

Nondepolarizing skeletal muscle relaxants |

May potentiate the effects of the muscle relaxant resulting in apnea1 |

Monitor for apnea208 |

|

NSAIAs |

Concomitant NSAIAs and aspirin (analgesic dosages): Therapeutic effect not greater than that of NSAIAs alone;208 increased risk for bleeding and serious GI events198 208 Aspirin: No consistent evidence that low-dose aspirin mitigates the increased risk of serious cardiovascular events associated with NSAIAs198 502 508 Therapeutic anti-inflammatory concentrations of salicylates (300 mcg/mL) may displace ketorolac from binding sites; ibuprofen, naproxen, or piroxicam does not alter the protein binding of ketorolac1 91 Protein binding of NSAIAs reduced by aspirin, but clearance of unbound NSAIA not altered; clinical importance unknown208 |

Concomitant use of ketorolac and analgesic dosages of aspirin generally not recommended;208 manufacturers of oral and parenteral ketorolac state concomitant use with aspirin or other NSAIAs is contraindicated207 1201 Advise patients receiving ketorolac not to take low-dose aspirin without consulting clinician;198 208 closely monitor patients receiving concomitant antiplatelet agents, including aspirin, for bleeding208 |

|

Oxymetazoline, intranasal |

Intranasal ketorolac: No change in rate or extent of ketorolac absorption in individuals with symptomatic allergic rhinitis208 |

|

|

Pemetrexed |

Possible increased risk of pemetrexed-associated myelosuppression, renal toxicity, and GI toxicity208 |

Short half-life NSAIAs (e. g., diclofenac, indomethacin): Avoid beginning 2 days before and continuing through 2 days after pemetrexed administration208 Longer half-life NSAIAs (e.g., meloxicam, nabumetone): In the absence of data, avoid beginning at least 5 days before and continuing through 2 days after pemetrexed administration208 Patients with Clcr 45–79 mL/minute: Monitor for myelosuppression, renal toxicity, and GI toxicity208 |

|

Pentoxifylline |

||

|

Probenecid |

Increased plasma concentrations and AUC of ketorolac1 |

|

|

Psychotherapeutic agents (e.g., fluoxetine, thiothixene, alprazolam) |

Hallucinations reported1 |

Monitor for hallucinations208 |

|

Serotonin-reuptake Inhibitors (e.g., SSRIs, SNRIs) |

Possible increased risk of bleeding due to importance of serotonin release by platelets in hemostasis208 |

Monitor for bleeding208 |

|

Thrombolytic agents |

Possible increased risk of bleeding1 |

|

|

Tolbutamide |

||

|

Warfarin |

Increased risk of bleeding complications;1 concurrent use not studied extensively1 Possible slight displacement of warfarin (but not ketorolac) from binding sites;1 91 other pharmacokinetic interactions unlikely1 |

Extreme caution advised in patients receiving therapeutic doses of warfarin;1 91 145 154 carefully monitor patients1 91 145 154 |

Ketorolac Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

IM: Rapidly and completely absorbed.1 2 36 37 38 140 173

Oral: Rapidly and almost completed absorbed; 1 2 36 37 38 70 95 173 bioavailability reported to be 80–100%.1 2 36 37 38 70 95 173

Intranasal: Bioavailability approximately 60% compared with IM injection.208 Peak concentrations achieved at about 45 minutes.208 Presence of allergic rhinitis does not substantially alter pharmacokinetics.208

Onset

IM administration: Onset in 10 minutes, with peak analgesia at 75–150 minutes.1 47 50 51 53

Oral administration: Onset in 30–60 minutes, with peak analgesia at 1.5–4 hours.55 56 57 58 59 60 61 137 138

Duration

Oral or IM administration: 6–8 hours.47 50 51 53 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 137 138

Food

Food decreases rate but not extent of absorption.1 2 70 83

Special Populations

Rate of absorption from GI tract may be decreased in patients with hepatic43 70 or renal44 70 impairment and in geriatric individuals.43 70

Distribution

Extent

Not distributed widely.1 2 37 70 140 Crosses the blood-brain barrier poorly.1 91

Crosses the placenta;1 2 41 65 91 173 distributed into milk.1 40 70 91 92

Intranasal: Most of dose is deposited in nasal cavity and pharynx; <20% is deposited in esophagus and stomach, and <0.5% is deposited in lungs.208

Plasma Protein Binding

Elimination

Metabolism

Metabolized in the liver by hydroxylation; 1 91 also undergoes conjugation with glucuronic acid.1 37 38 173

Elimination Route

Excreted in urine (92%) as parent drug (60%) or metabolites (40%) and in feces (6%).1 38 70 173

Half-life

4–6 hours in adults;1 2 36 37 38 70 80 91 97 140 173 208 3.8–6.1 hours in pediatric patients.1 173 197

Special Populations

Hepatic impairment (e.g., cirrhosis) does not appear to substantially affect half-life.1 2 43 173 In patients with cirrhosis, half-life of about 4.5–5.4 hours reported.1 43 91 173

Renal impairment: Half-life is about 9–10 hours (range: 3.2–19 hours);1 2 44 91 173 in patients undergoing dialysis, half-life of about 13.6 hours (range: 8–39.1 hours) reported.1

Geriatric individuals: Half-life is about 5–7 hours (range: 4.3–8.6 hours).1 2 42 70 80 91 173

Stability

Storage

Nasal

Solution

Unopened: 2–8°C; protect from light and freezing.208 During use: 15–20°C out of direct sunlight.208 Discard within 24 hours after priming the spray pump.208

Oral

Tablets

15–30°C.1

Parenteral

Injection

15–30°C; protect from light.1

Compatibility

Parenteral

Solution Compatibility212

|

Compatible |

|---|

|

Dextrose 5% in sodium chloride 0.9% |

|

Dextrose 5% in water |

|

Plasma-Lyte A, pH 7.4 |

|

Ringer’s injection |

|

Ringer’s injection, lactated |

|

Sodium chloride 0.9% |

Drug Compatibility

|

Incompatible |

|---|

|

Cyclizine lactate |

|

Haloperidol lactate |

|

Hydroxyzine HCl |

|

Meperidine HCl |

|

Morphine Sulfate |

|

Nalbuphine |

|

Prochlorperazine edisylate |

|

Promethazine HCl |

|

Variable |

|

Diazepam |

|

Hydromorphone HCl |

Ketorolac tromethamine 1 mg/mL tested.212

|

Compatible |

|---|

|

Acetaminophen |

|

Dexmedetomidine HCl |

|

Fentanyl citrate |

|

Hetastarch in lactated electrolyte injection (Hextend) |

|

Hydromorphone HCl |

|

Methadone HCl |

|

Morphine sulfate |

|

Remifentanil HCl |

|

Incompatible |

|

Azithromycin |

|

Fenoldopam mesylate |

|

Variable |

|

Cisatracurium besylate |

Actions

-

Inhibits cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and COX-2.91

-

Pharmacologic actions similar to those of other prototypical NSAIAs; 2 21 32 33 91 exhibits anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic activity.1 2 21 32 33 70 91 140

Advice to Patients

-

Importance of reading the medication guide for NSAIAs that is provided each time the drug is dispensed.198

-

Risk of serious cardiovascular events (e.g., MI, stroke).198 500 508 Importance of seeking immediate medical attention if signs and symptoms of a cardiovascular event (e.g., chest pain, dyspnea, weakness, slurred speech) occur.198 500 508

-

Risk of GI bleeding and ulceration.1 167 181 Importance of notifying clinician if signs and symptoms of GI ulceration or bleeding develop.1

-

Risk of bleeding following tonsillectomy.1

-

Risk of serious skin reactions,198 DRESS,1201 and anaphylactic and other sensitivity reactions.1 Advise patients to stop taking ketorolac immediately if they develop any type of rash or fever and to promptly contact their clinician.1201 Importance of seeking immediate medical attention if an anaphylactic reaction occurs.1

-

Risk of hepatotoxicity.1 Importance of discontinuing therapy and contacting clinician immediately if signs and symptoms of hepatotoxicity (e.g., nausea, fatigue, lethargy, pruritus, jaundice, upper right quadrant tenderness, flu-like symptoms) occur.198

-

Risk of kidney failure.1

-

Risk of heart failure or edema; importance of reporting dyspnea, unexplained weight gain, or edema.508

-

Importance of women informing clinicians if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1

-

Importance of avoiding NSAIA use beginning at 20 weeks’ gestation unless otherwise advised by a clinician; importance of avoiding NSAIAs beginning at 30 weeks’ gestation because of risk of premature closure of the fetal ductus arteriosus; monitoring for oligohydramnios may be necessary if NSAIA therapy required for >48 hours’ duration between about 20 and 30 weeks’ gestation.1200 1201

-

Advise women who are trying to conceive that NSAIAs may be associated with a reversible delay in ovulation.208

-

Importance of not exceeding recommended duration of therapy.1

-

Importance of informing clinicians of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs.1

-

Importance of informing patients of other important precautionary information.1 (See Cautions.)

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nasal |

Solution |

15.75 mg/metered spray |

Sprix |

Zyla |

|

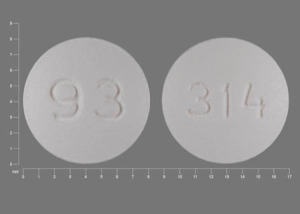

Oral |

Tablets, film-coated |

10 mg* |

Ketorolac Tromethamine Tablets |

|

|

Parenteral |

Injection, for IM or IV use |

15 mg/mL* |

Ketorolac Tromethamine Injection |

|

|

30 mg/mL* |

Ketorolac Tromethamine Injection |

|||

|

Injection, for IM use |

30 mg/mL* |

Ketorolac Tromethamine Injection |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2024, Selected Revisions October 18, 2021. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

References

1. Roche Laboratories. Toradol IV, IM, and oral (ketorolac tromethamine) prescribing information. Nutley, NJ; 2002 Sep.

2. Gannon R. Focus on ketorolac: a nonsteroidal, anti-inflammatory agent for the treatment of moderate to severe pain. Hosp Formul. 1989; 24:695-702.

3. Budavari S, ed. The Merck index. 11th ed. Rahway, NJ: Merck & Co, Inc; 1989:836.

4. Gu L, Chiang HS, Johnson D. Light degradation of ketorolac tromethamine. Int J Pharm. 1988; 41:105-13.

5. Guzman A, Yuste F, Toscano RA et al. Absolute configuration of (-)-5-benzoyl-1,2-dihydro-3H -pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrrole-1-carboxylic acid, the active enantiomer of ketorolac. J Med Chem. 1986; 29:589-91. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3959034?dopt=AbstractPlus

6. Wilson DE. Antisecretory and mucosal protective actions of misoprostol. Am J Med. 1987; 83(Suppl 1A):2-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3113241?dopt=AbstractPlus

7. Aadland E, Fausa O, Vatn M et al. Protection by misoprostol against naproxen-induced gastric mucosal damage. Am J Med. 1987; 83(Suppl 1A):37-40. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3113244?dopt=AbstractPlus

8. Rainsford KD, Willis C. Relationship of gastric mucosal damage induced in pigs by antiinflammatory drugs to their effects on prostaglandin production. Dig Dis Sci. 1982; 27:624-35. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6953009?dopt=AbstractPlus

9. Kobayashi K, Arakawa T, Satoh H et al. Effect of indomethacin, tiaprofenic acid and dicrofenac on rat gastric mucosal damage and content of prostacyclin and prostaglandin E2. Prostaglandins. 1985; 30: 609-18. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3909233?dopt=AbstractPlus

10. Oliw E, Lunden I, Anggard E. In vivo inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis in rabbit kidney by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh). 1978; 42:179-84. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/580346?dopt=AbstractPlus

11. Abramson S, Edelson H, Kaplan H et al. Inhibition of neutrophil activation by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med. 1984; 10:3-6.

12. Moncada S, Flower RJ, Vane JR. Prostaglandins, prostacyclin, thromboxane A2, and leukotrienes. In: Gilman AG, Goodman LS, Rall TW et al, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 7th ed. New York; Macmillan Publishing Company; 1985: 660-73.

13. Deraedt R, Jouquey S, Benzoni J et al. Inhibition of prostaglandin biosynthesis by non-narcotic analgesic drugs. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1976; 224:30-42. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13749?dopt=AbstractPlus

14. Atkinson DC, Collier HOJ. Salicylates: molecular mechanism of therapeutic action. Adv Pharmacol Chemother. 1980; 17:233-88. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7004141?dopt=AbstractPlus

15. Robinson DR. Prostaglandins and the mechanism of action of anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med. 1983; 10:26-31.

16. O’Brien WM. Pharmacology of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med. 1983; 10:32-9.

17. Koch-Weser J. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1980; 302:1179-85. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6988717?dopt=AbstractPlus

18. Ferreira SH, Lorenzetti BB, Correa FMA. Central and peripheral antialgesic action of aspirin-like drugs. Eur J Pharmacol. 1978; 53:39-48. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/310771?dopt=AbstractPlus

19. Hart FD. Rheumatic disorders. In: Avery GS, ed. Drug treatment: principles and practice of clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2nd ed. New York: ADIS Press; 1987:846-61.

20. Bernheim HA, Block LH, Atkins E. Fever: pathogenesis, pathophysiology, and purpose. Ann Intern Med. 1979; 91:261-70. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/223485?dopt=AbstractPlus

21. Rooks WH II, Tomolonis AJ, Maloney PJ et al. The analgesic and anti-inflammatory profile of (±) -5-benzoyl-1,2-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[1,2a]pyrrole -1-carboxylic acid (RS-37619). Agents Actions. 1982; 12:684-90. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6984594?dopt=AbstractPlus

22. Fraser-Smith EB, Matthews TR. Effect of ketorolac on phagocytosis of candida albicans by peritoneal macrophages. Immunopharmacology. 1988; 16:151-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3075603?dopt=AbstractPlus

23. Conrad KA, Fagan TC, Mackie MJ et al. Effects of ketorolac tromethamine on hemostasis in volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988; 43:542-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3259170?dopt=AbstractPlus

24. Spowart K, Greer IA, McLaren M et al. Haemostatic effects of ketorolac with and without concomitant heparin in normal volunteers. Thromb Haemost. 1988; 60:382-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3266379?dopt=AbstractPlus

25. Murray AW, Brockway MS, Kenny GNC. Comparison of the cardiorespiratory effects of ketorolac and alfentanil during propofol anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1989; 63:601-3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2605079?dopt=AbstractPlus

26. Brandon Bravo LJC, Mattie H, Spierdijk J et al. The effects of ventilation of ketorolac in comparison with morphine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1988; 35:491-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3148470?dopt=AbstractPlus

27. Fraser-Smith EB, Matthews TR. Effect of ketorolac on pseudomonas aeruginosa ocular infection in rabbits. J Ocul Pharmacol. 1988; 4:101-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3262701?dopt=AbstractPlus

28. Fraser-Smith EB, Matthews TR. Effect of ketorolac on candida albicans ocular infection in rabbits. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987; 105:264-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3492994?dopt=AbstractPlus

29. Fraser-Smith EB, Matthews TR. Effect of ketorolac on herpes simplex virus type one ocular infection in rabbits. J Ocul Pharmacol. 1988; 4: 321-6.

30. Oates JA, FitzGerald GA, Branch RA et al. Clinical implications of prostaglandin and thromboxane A2 formation (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1988; 319:689-98. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3045550?dopt=AbstractPlus

31. Lanza FL, Karlin DA, Yee JP. A double-blind placebo controlled endoscopic study comparing the mucosal injury seen with an orally and parenterally administered new nonsteroidal analgesic ketorolac tromethamine at therapeutic and supratherapeutic doses. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987; 82:939.

32. Rooks WH II, Maloney PJ, Shott LD et al. The analgesic and anti-inflammatory profile of ketorolac and its tromethamine salt. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1985; 11:479-92. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3879752?dopt=AbstractPlus

33. Muchowski JM, Unger SH, Ackrell J et al. Synthesis and antiinflammatory and analgesic activity of 5-aroyl-1,2-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[1,2-a] pyrrole-1-carboxylic acids and related compounds. J Med Chem. 1985; 28:1037-49. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4020827?dopt=AbstractPlus

34. Roe RL, Bruno JJ, Ellis DJ. Effects of a new nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent on platelet function in male and female subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981; 29:277.

35. Rubin P, Yee JP, Murthy VS et al. Ketorolac tromethamine (KT) analgesia: no post-operative respiratory depression and less constipation. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1987; 41:182.

36. Jung D, Mroszczak EJ, Wu A et al. Pharmacokinetics of ketorolac and p-hydroxyketorolac following oral and intramuscular administration of ketorolac tromethamine. Pharm Res. 1989; 6:62-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2717521?dopt=AbstractPlus

37. Jung D, Mroszczak E, Bynum L. Pharmacokinetics of ketorolac tromethamine in humans after intravenous, intramuscular and oral administration. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1988; 35:423-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3264245?dopt=AbstractPlus

38. Mroszczak EJ, Lee FW, Combs D et al. Ketorolac tromethamine absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and pharmacokinetics in animals and humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 1987; 15:618-26. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2891477?dopt=AbstractPlus

39. Gu L, Chiang HS, Becker A. Kinetics and mechanisms of the autoxidation of ketorolac tromethamine in aqueous solution. Int J Pharm. 1988; 41:95-104.

40. Wischnik A, Manth SM, Lloyd J. The excretion of ketorolac tromethamine into breast milk after multiple oral dosing. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1989; 36:521-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2787750?dopt=AbstractPlus

41. Walker JJ, Johnstone J, Lloyd J et al. The transfer of ketorolac tromethamine from maternal to foetal blood. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1988; 34:509-11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3264528?dopt=AbstractPlus

42. Montoya-Iraheta C, Garg DC, Jallad NS et al. Pharmacokinetics of single dose oral and intramuscular ketorolac tromethamine in elderly vs. young healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 1986; 26:545.

43. Pages LJ, Martinez JJ, Garg DC et al. Pharmacokinetics of ketorolac tromethamine in hepatically impaired vs. young healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 1987; 27:724.

44. Martinez JJ, Garg DC, Pages LJ et al. Single dose pharmacokinetics of ketorolac in healthy young and renal impaired subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 1987; 27:722.

45. Ling TL, Combs DL. Ocular bioavailability and tissue distribution of [14C]ketorolac tromethamine in rabbits. J Pharm Sci. 1987; 76: 289-94. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3598886?dopt=AbstractPlus

46. Mroszczak EJ, Ling T, Yee J et al. Ketorolac tromethamine (KT) absorption and pharmacokinetics in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1985; 37:215.

47. Yee JP, Koshiver JE, Allbon C et al. Comparison of intramuscular ketorolac tromethamine and morphine sulfate for analgesia of pain after major surgery. Pharmacotherapy. 1986; 6:253-61. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3540877?dopt=AbstractPlus

48. Yee J, Brown C, Allison C et al. Analgesia from intramuscular ketorolac tromethamine compared to morphine (MS) in “severe” pain following “major” surgery. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1985; 37:239.

49. Gillies GWA, Kenny GNC, Bullingham RES et al. The morphine sparing effect of ketorolac tromethamine. Anaesthesia. 1987; 42:727-31. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3307518?dopt=AbstractPlus

50. O’Hara DA, Fragen RJ, Kinzer M et al. Ketorolac tromethamine as compared with morphine sulfate for treatment of postoperative pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1987; 41:556-61. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3568540?dopt=AbstractPlus

51. Estenne B, Julien M, Charleux H et al. Comparison of ketorolac, pentazocine, and placebo in treating postoperative pain. Curr Ther Res. 1988; 43:1173-82.

52. Brown CR, Wild VM, Bynum L. Comparison of intravenous ketorolac tromethamine and morphine sulfate in postoperative pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988; 43:142.

53. Staquet MJ. A double-blind study with placebo control of intramuscular ketorolac tromethamine in the treatment of cancer pain. J Clin Pharmacol. 1989; 29:1031-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2689472?dopt=AbstractPlus

54. Fricke J, Angelocci D. The analgesic efficacy of I.M. ketorolac and meperidine for the control of postoperative dental pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1987; 41:181.

55. McQuay HJ, Poppleton P, Carroll D et al. Ketorolac and acetaminophen for orthopedic postoperative pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1986; 39: 89-93. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3510797?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2954767&blobtype=pdf

56. Vangen O, Doessland S, Lindbaek E. Comparative study of ketorolac and paracetamol/codeine in alleviating pain following gynaecological surgery. J Int Med Res. 1988; 16:443-51. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3069519?dopt=AbstractPlus

57. Johansson S, Josefsson G, Malstam J et al. Analgesic efficacy and safety comparison of ketorolac tromethamine and doleron for the alleviation of orthopaedic post-operative pain. J Int Med Res. 1989; 17:324-32. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2676649?dopt=AbstractPlus

58. Kagi P. A multiple-dose comparison of oral ketorolac and pentazocine in the treatment of postoperative pain. Curr Ther Res. 1989; 45:1049-59.

59. Galasko CSB, Russel S, Lloyd J. Double-blind investigation of the efficacy of multiple oral doses of ketorolac tromethamine compared with dihydrocodeine and placebo. Curr Ther Res. 1989; 45:844-52.

60. Honig WJ, Van Ochten J. A multiple-dose comparison of ketorolac tromethamine with diflunisal and placebo in postmeniscectomy pain. J Clin Pharmacol. 1986; 26:700-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3540032?dopt=AbstractPlus

61. Arsac M, Frileux C. Comparative analgesic efficacy and tolerability of ketorolac tromethamine and glafenine in patients with post-operative pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 1988; 11:214-20. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2905636?dopt=AbstractPlus

62. Flach AJ, Graham J, Kruger LP et al. Quantitative assessment of postsurgical breakdown of the blood-aqueous barrier following administration of 0.5% ketorolac tromethamine solution. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988; 106:344-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3345153?dopt=AbstractPlus

63. Flach AJ, Kraff MC, Sanders DR et al. The quantitative effect of 0.5% ketorolac tromethamine solution and 0.1% dexamethasone sodium phosphate solution on postsurgical blood-aqueous barrier. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988; 106:480-3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3355415?dopt=AbstractPlus

64. Flach AJ, Dolan BJ, Irvine AR. Effectiveness of ketorolac tromethamine 0.5% ophthalmic solution for chronic aphakic and pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987; 103:479-86. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3551617?dopt=AbstractPlus

65. Greer IA, Johnston J, Tulloch I et al. Effect of maternal ketorolac administration on platelet function in the newborn. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1988; 29:257-60. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3265921?dopt=AbstractPlus

66. Macdonald FC, Gough KJ, Nicoll RAG et al. Psychomotor effects of ketorolac in comparison with buprenorphine and diclofenac. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989; 27:453-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2785813?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1379724&blobtype=pdf

67. Saarialho-Kere U. Psychomotor effects of ketorolac. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989; 28:495. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2590610?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1380004&blobtype=pdf

68. Yee J, Bradley R, Stanski D et al. A comparison of analgesic efficacy of intramuscular ketorolac tromethamine and meperidine in postoperative pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1986; 39:237.

69. Floy BJ, Royko CG, Fleitman JS. Compatibility of ketorolac tromethamine injection with common infusion fluids and administration sets. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990; 47:1097-100. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2337102?dopt=AbstractPlus

70. Buckley MMT, Brogden RN. Ketorolac: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic potential. Drugs. 1990; 39:86-109. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2178916?dopt=AbstractPlus

71. Sunshine A, Richman H, Cordone R et al. Analgesic efficacy and onset of oral ketorolac in postoperative pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988; 43:159.

72. Brown CR, Moodie JE, Evans SA et al. Efficacy of intramuscular (I.M.) ketorolac and meperidine in pain following major oral surgery. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988; 43:161.

73. Bloomfield SS, Cissell G, Peters N et al. Ketorolac analgesia for postoperative pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988; 43:160.

74. Rubin P, Murthy VS, Yee J. Long-term safety and efficacy comparison study of ketorolac tromethamine (KT) and aspirin (ASA) in the treatment of chronic pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1987; 41:229.

75. Forbes JA, Butterworth GA, Kehm CK et al. Two clinical evaluations of ketorolac tromethamine in postoperative oral surgery pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1987; 41:162.

76. Yee J, Brown CR, Sevelius H et al. The analgesic efficacy of (±)-5-benzoyl-1,2-dihydro -3H-pyrrolo [1,2a] pyrrole-1-carboxylic acid, tromethamine salt (B) in post-operative pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984; 35:285.

77. Flach AJ, Jaffe NS, Akers WA. The effect of ketorolac tromethamine in reducing postoperative inflammation: double-mask parallel comparison with dexamethasone. Ann Ophthalmol. 1989; 21:407-11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2619149?dopt=AbstractPlus

78. Haynes WL, Proia AD, Klintworth GK. Effect of inhibitors of arachidonic acid metabolism on corneal neovascularization in the rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989; 30:1588-93. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2473047?dopt=AbstractPlus

79. Domer F. Characterization of the analgesic activity of ketorolac in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990; 177:127-35. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2311674?dopt=AbstractPlus

80. Jallad NS, Garg DC, Martinez JJ et al. Pharmacokinetics of single-dose oral and intramuscular ketorolac tromethamine in the young and elderly. J Clin Pharmacol. 1990; 30:76-81. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2303585?dopt=AbstractPlus

81. Staquet M, Lloyd J, Bullingham R. The comparative efficacy of single doses of ketorolac tromethamine (KT) and placebo (P) to relieve cancer pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988; 43:159.

82. Flach AJ, Lavelle CJ, Olander KW et al. The effect of ketorolac tromethamine solution 0.5% in reducing postoperative inflammation after cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantation. Ophthalmology. 1988; 95:1279-84. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3062540?dopt=AbstractPlus

83. Bloomfield SS, Mitchell J, Cissell GB et al. Ketorolac versus aspirin for postpartum uterine pain. Pharmacotherapy. 1986; 6:247-52. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3540876?dopt=AbstractPlus

84. Adams DH, Howie AJ, Michael J et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and renal failure. Lancet. 1986; 1:57-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2867313?dopt=AbstractPlus

85. Weinberger M. Analgesic sensitivity in children with asthma. Pediatrics. 1978; 62(Suppl):910-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/103067?dopt=AbstractPlus

86. Pleskow WW, Stevenson DD, Mathison DA et al. Aspirin desensitization in aspirin-sensitive asthmatic patients: clinical manifestations and characterization of the refractory period. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1982; 69(1 Part 1):11-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7054250?dopt=AbstractPlus

87. VanArsdel PP Jr. Aspirin idiosyncracy and tolerance. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1984; 73:431-3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6423718?dopt=AbstractPlus

88. Stevenson DD. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of adverse reactions to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1984; 74(4 Part 2):617-22. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6436354?dopt=AbstractPlus

89. Stevenson DD, Mathison DA. Aspirin sensitivity in asthmatics: when may this drug be safe? Postgrad Med. 1985; 78:111-3,116-9. (IDIS 205854)

90. Settipane GA. Aspirin and allergic diseases: a review. Am J Med. 1983; 74(Suppl):102-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6344621?dopt=AbstractPlus

91. Syntex Laboratories Inc. Toradol product monograph. Palo Alto, CA; 1992 Apr.

92. Syntex Laboratories Inc. Toradol pharmacy information. Palo Alto, CA; 1990 Mar.

93. Syntex Laboratories Inc. Toradol formulary facts. Palo Alto, CA; 1990.

94. Mahoney JM, Waterbury LD. Drug effects on the neovascularization response to silver nitrate cauterization of the rat cornea. Curr Eye Res. 1985; 4:531-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2410194?dopt=AbstractPlus

95. Lee F, Mroszczak E, Fass M et al. Ketorolac tromethamine (KT) absorption, metabolism and pharmacokinetics in animals and man. Fed Proc. 1985; 44:1118.

96. Hillier K. Ketorolac. Drugs Future. 1981; 6:669-70.

97. Sarnquist FH, Mroszczak EJ, Sevelius H. Absorption and metabolism of a new anti-inflammatory, analgesic agent. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981; 29:280.

98. Bruno JJ, Yang D, Taylor LA. Differing effects of ticlopidine and two prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors on maximum rate of ADP-induced aggregation. Thromb Haemost. 1981; 46:412.

99. Fragen RJ, O’Hara D. A comparison of intramuscularly injected ketorolac and morphine in postoperative pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1987; 41:212.

100. Yee JP, Waterbury LD. Ketorolac tromethamine is a new analgesic with efficacy comparable to morphine that does not bind to opioid receptors and has low addictive potential. Clin Res. 1987; 35:163A.

101. Hougard K, Kjaergard J, Andersen HB et al. Ketorolac and ketobemidone for postoperative pain: a randomised study. Pain. 1987; 5(Suppl 4):S56.

102. Mehlisch D. Safety of intramuscular administered ketorolac tromethamine in subjects age 65 and over. Pain. 1987; 5(Suppl 4):S304.

103. Lopez M, Waterbury LD, Michel A et al. Lack of addictive potential of ketorolac tromethamine. Pharmacologist. 1987; 29:136.

104. Brater DC. Drug-drug and drug-disease interactions with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med. 1986; 80(Suppl 1A):62-70. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3511686?dopt=AbstractPlus

105. Ellison NM, Servi RJ. Acute renal failure and death following sequential intermediate-dose methotrexate and 5-FU: a possible adverse effect due to concomitant indomethacin administration. Cancer Treat Rep. 1985; 69:342-3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3978662?dopt=AbstractPlus

106. Singh RR, Malaviya AN, Pandey JN et al. Fatal interaction between methotrexate and naproxen. Lancet. 1986; 1:1390. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2872507?dopt=AbstractPlus

107. Day RO, Graham GG, Champion GD et al. Anti-rheumatic drug interactions. Clin Rheum Dis. 1984; 10:251-75. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6150784?dopt=AbstractPlus

108. Daly HM, Scott GL, Boyle J et al. Methotrexate toxicity precipitated by azapropazone. Br J Dermatol. 1986; 114:733-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3718865?dopt=AbstractPlus

109. Hansten PD, Horn JR. Methotrexate interactions: ketoprofen (Orudis). Drug Interact Newsl. 1986; 6(Updates):U5-6.

110. Maiche AG. Acute renal failure due to concomitant action of methotrexate and indomethacin. Lancet. 1986; 1:1390. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2872506?dopt=AbstractPlus

111. Thyss A, Milano G, Kubar J et al. Clinical and pharmacokinetic evidence of a life-threatening interaction between methotrexate and ketoprofen. Lancet. 1986; 1:256-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2868265?dopt=AbstractPlus

112. Reviewers’ comments (personal observations): ketoprofen; 1986 Aug.

113. Singer L, Imbs JL, Danion JM et al. Risque d’intoxication par le lithium en cas de traitement associé par les anti-inflammatoires non steroidiens. (French; with English abstract.) Therapie. 1981; 36:323-6.

114. Reimann IW, Frolich JC. Effects of diclofenac on lithium kinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981; 30:348-52. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7273598?dopt=AbstractPlus

115. D’Arcy PF. Drug interactions with new drugs. Pharm Int. 1983; 4:285-91.

116. Monk JP, Clissold SP. Misoprostol: a preliminary review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of peptic ulcer disease. Drugs. 1987; 33:1-30. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3102205?dopt=AbstractPlus

117. Wilson DE. Misoprostol and gastroduodenal mucosal protection (cytoprotection). Postgrad Med J. 1988; 64(Suppl 1):7-11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3138683?dopt=AbstractPlus

118. Miller TA. Protective effects of prostaglandins against gastric mucosal damage: current knowledge and proposed mechanisms. Am J Physiol. 1983; 245:G601-23. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6195926?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2879877&blobtype=pdf

119. Konturek SJ, Pawlik W. Physiology and pharmacology of prostaglandins. Dig Dis Sci. 1986; 31(Suppl):6-19S.

120. Taha AS, McLaughlin S, Holland PJ et al. Prevention of NSAID-induced gastric ulcer with prostaglandin analogues. Lancet. 1989; 1:52. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2563038?dopt=AbstractPlus

121. Fromm D. How do non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs affect gastric mucosal defenses? Clin Invest Med. 1987; 10:251-8.

122. Hawkey CJ. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and peptic ulcers. Br Med J. 1990; 300:278-84.

123. Schoen RT, Vender RJ. Mechanisms of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastric damage. Am J Med. 1989; 86:449-58. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2648824?dopt=AbstractPlus

124. Roth SH. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: gastropathy, deaths, and medical practice. Ann Intern Med. 1988; 109:353-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3044208?dopt=AbstractPlus

125. Griffin MR, Ray WA, Schaffner W. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and death from peptic ulcer in elderly persons. Ann Intern Med. 1988; 109:359-63. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3261560?dopt=AbstractPlus

126. Masi AT. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and peptic ulcer. Ann Intern Med. 1989; 110:246-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2912366?dopt=AbstractPlus

127. Griffin MR, Ray WA, Schaffner W. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and peptic ulcer. Ann Intern Med. 1989; 110:247. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2912367?dopt=AbstractPlus

128. Wolf RE. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Arch Intern Med. 1984; 144:1658-60. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6235791?dopt=AbstractPlus

129. Clive DM, Stoff JS. Renal syndromes associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1984; 310:563-72. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6363936?dopt=AbstractPlus

130. Henrich WL. Nephrotoxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Am J Kidney Dis. 1983; 2:478-84. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6823966?dopt=AbstractPlus

131. Kimberly RP, Bowden RE, Keiser HR et al. Reduction of renal function by newer nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med. 1978; 64:804-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/645744?dopt=AbstractPlus

132. Corwin HL, Bonventre JV. Renal insufficiency associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Am J Kidney Dis. 1984; 4:147-52. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6475945?dopt=AbstractPlus

133. Indocin (indomethacin capsules, oral suspension, and suppositories USP) prescribing information. In: Barnhart ER, ed. Physicians’ desk reference. 44th ed. Oradell, NJ: Medical Economics Company Inc; 1990:1395-8.

134. Brown CR. Results from three studies of the multiple-dose safety and efficacy of intramuscularly (IM) administered ketorolac tromethamine in patients with pain from major surgery. In: Abstracts of the Fifth World Congress on Pain, Hamburg, FRG, 2–7 August 1987. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1987. Abstract No. 4.

135. Camu F, Van Overberghe L, Bullingham R et al. Hemodynamic effects of ketorolac tromethamine in comparison to morphine in anesthetised patients. In: 9th World Congress of Anaesthesiologists, Abstracts Volume I: Scientific Papers A0001 to A0506. May 22-28, 1988. USA, 1988:A0167. Abstract.

136. Brandon Bravo LJC, Mattie H, Spierdijk J et al. A study of the comparative effects on respiration of ketorolac tromethamine and morphine. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh). 1986; 59(Suppl 5):119.

137. Syntex Laboratories, Inc, Palo Alto, CA.

138. Reviewers comments (personal observations); 1990 Jul.

139. Gu L, Strickley RG. Preformulation salt selection. Physical property comparisons of the tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (THAM) salts of four analgesic/antiinflammatory agents with the sodium salts and the free acids. Pharm Res. 1987; 4:255-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3509292?dopt=AbstractPlus

140. Anon. Ketorolac tromethamine. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1990; 32:97-82.

141. Soll AH, Weinstein WM, Kurata J et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and peptic ulcer disease. Ann Intern Med. 1991; 114:307-19. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1987878?dopt=AbstractPlus

142. Hagler L, Medd BH. Dear doctor letter regarding safety information related to the appropriate use of ketorolac tromethamine. Palo Alto, CA: Syntex; 1993 Oct.

143. Choo V, Lewis S. Ketorolac doses reduced. Lancet. 1993; 342:109. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8100870?dopt=AbstractPlus

144. Anon. Syntex Toradol labeling changes reported in “dear doctor” letter. Prescription Pharm Biotechnol. 1993; Nov 1:9-10.

145. McDonald E, Marino C, Schwartz E et al. Toradol and the risk of gastrointestinal complications in the elderly. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 1993; 41:90-1.

146. Zikowski D, Hord AH, Haddox JD et al. Ketorolac-induced bronchospasm. Anesth Analg. 1993; 76:417-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8424524?dopt=AbstractPlus

147. Pearce CJ, Gonzalez FM, Wallin JD. Renal failure and hyperkalemia associated with ketorolac tromethamine. Arch Intern Med. 1993; 153:1000-2. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8481061?dopt=AbstractPlus

148. Haddow GR, Riley E, Isaacs R et al. Ketorolac, nasal polyposis, and bronchial asthma: a cause for concern. Anesth Analg. 1993; 76:420-2. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8424525?dopt=AbstractPlus

149. Fuller DK, Kalekas PJ. Ketorolac and gastrointestinal ulceration. Ann Pharmacother. 1993; 27:978-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8364288?dopt=AbstractPlus

150. Estes LL, Fuhs DW, Heaton AH et al. Gastric ulcer perforation associated with the use of injectable ketorolac. Ann Pharmacother. 1993; 27:42-3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8431619?dopt=AbstractPlus

151. Goetz CM, Sterchele JA, Harchelroad FP. Anaphylactoid reaction following ketorolac tromethamine administration. Ann Pharmacother. 1992; 26:1237-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1421646?dopt=AbstractPlus

152. Rotenberg FA, Giannini VS. Hyperkalemia associated with ketorolac. Ann Pharmacother. 1992; 26:778-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1611159?dopt=AbstractPlus

153. The United States pharmacopeia, 23rd rev, and The national formulary, 18th ed. Rockville, MD: The United States Pharmacopeial Convention, Inc; 1994(Suppl 1):2473-4.

154. Carter ML. Dear doctor letter regarding important drug warnings and labeling changes for ketorolac tromethamine. Nutley, NJ: Roche Laboratories; 1995 Feb.

155. Perlin E, Finke H, Castro O et al. Enhancement of pain control with ketorolac tromethamine in patients with sickle cell vasoocclusive crisis. Am J Hematol. 1994; 46:43-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7514356?dopt=AbstractPlus

156. Goodman E. Use of ketorolac in sickle-cell disease and vasoocclusive crisis. Lancet. 1991; 338:641-2. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1679183?dopt=AbstractPlus

157. Iyer I. Ketorolac (Toradol) induced lithium toxicity. Headache. 1994; 34:442-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7928331?dopt=AbstractPlus

158. Langlois R, Paquette D. Increased serum lithium levels due to ketorolac therapy. CMAJ. 1994; 150:1455-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8168010?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1486635&blobtype=pdf

159. Morrison NA, Repka MX. Ketorolac versus acetaminophen or ibuprofen in controlling postoperative pain in patients with strabismus. Ophthalmology. 1994; 101:915-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8190480?dopt=AbstractPlus

160. Myers KG, Trotman IF. Use of ketorolac by continuous subcutaneous infusion for the control of cancer-related pain. Postgrad Med J. 1994; 70:359-62. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8016008?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=PMC2397591&blobtype=pdf

161. Ready LB, Brown CR, Stahlgren LH et al. Evaluation of intravenous ketorolac administered by bolus or infusion for treatment of postoperative pain: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Anesthesiology. 1994; 80:1277-86. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8010474?dopt=AbstractPlus

162. Sevarino FB, Sinatra RS, Paige D et al. Intravenous ketorolac as an adjunct to patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) for management of postgynecologic surgical pain. J Clin Anesth. 1994; 6:23-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8142094?dopt=AbstractPlus

163. Larsen LS, Miller A, Allegra JR. The use of intravenous ketorolac for the treatment of renal colic in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 1993; 11:197-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8489656?dopt=AbstractPlus

164. Miller LJ, Kramer MA. Pain management with intravenous ketorolac. 1993; 27:307-8.

165. Wong HY, Carpenter RL, Kopacz DJ et al. A randomized, double-blind evaluation of ketorolac tromethamine for postoperative analgesia in ambulatory surgery patients. Anesthesiolgy. 1993; 41:90-1.

166. Haragsim L, Dalal R, Bagga H et al. Ketorolac-induced acute renal failure and hyperkalemia: report of three cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994; 24:578-80. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7942813?dopt=AbstractPlus

167. Perazella MA, Buller GK. NSAID nephrotoxicity revisited: acute renal failure due to parenteral ketorolac. South Med J. 1993; 86:1421-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8272928?dopt=AbstractPlus

168. Quan DJ, Kayser SR. Ketorolac-induced acute renal failure following a single dose. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1994; 32:305-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8007038?dopt=AbstractPlus

169. Shapiro N. Acute angioedema after ketorolac ingestion: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 52:626-7.

170. Corelli RL, Gericke KR. Renal insufficiency associated with intramuscular administration of ketorolac tromethamine. Ann Pharmacother. 1993; 27:1055-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8219436?dopt=AbstractPlus

171. Schoch PH, Ranno A, North DS. Acute renal failure in an elderly woman following intramuscular ketorolac administration. Ann Pharmacother. 1992; 26:1233-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1421645?dopt=AbstractPlus

172. Maunuksela EL, Kokki H, Bullingham RE. Comparison of intravenous ketorolac with morphine for postoperative pain in children. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992; 52:436-43. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1424417?dopt=AbstractPlus

173. Brocks DR, Jamali F. Clinical pharmacokinetics of ketorolac tromethamine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1992; 23:415-27. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1458761?dopt=AbstractPlus

174. Rusy LM, Houck CS, Sullivan LJ et al. A double-blind evaluation of ketorolac tromethamine versus acetaminophen in pediatric tonsillectomy: analgesia and bleeding. Anesth Analg. 1995; 80:226-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7818104?dopt=AbstractPlus

175. Buck ML. Clinical experience with ketorolac in children. Ann Pharmacother. 1994; 28:1009-13. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7803871?dopt=AbstractPlus

176. Rubin P, Yee JP, Ruoff G. Comparison of long-term safety of ketorolac tromethamine and aspirin in the treatment of chronic pain. Pharmacotherapy. 1990; 10(6 Part 2):106S-10S. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2082305?dopt=AbstractPlus

177. Ciba Geigy, Ardsley, NY: Personal communication on diclofenac 28:08.04.

178. Reviewers’ comments (personal observations) on diclofenac 28:08.04.

179. Searle. Cytotec (misoprostol) prescribing information. 1989 Jun.

180. Corticosteroid interactions: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). In: Hansten PD, Horn JR. Drug interactions and updates. Vancouver WA: Applied Therapeutics, Inc; 1993:562.

181. Garcia Rodriguez LA, Jick H. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation associated with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Lancet. 1994; 343:769-72. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7907735?dopt=AbstractPlus

182. Hollander D. Gastrointestinal complications of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: prophylactic and therapeutic strategies. Am J Med. 1994; 96:274-81. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8154516?dopt=AbstractPlus

183. Schubert TT, Bologna SD, Yawer N et al. Ulcer risk factors: Interaction between Helicobacter pylori infection, nonsteroidal use, and age. Am J Med. 1993; 94:413-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8475935?dopt=AbstractPlus

184. Piper JM, Ray WA, Daugherty JR et al. Corticosteroid use and peptic ulcer disease: role of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Ann Intern Med. 1991; 114:735-40. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2012355?dopt=AbstractPlus

185. Bateman DN, Kennedy JG. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and elderly patients: the medicine may be worse than the disease. BMJ. 1995; 310:817-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7711609?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2549212&blobtype=pdf

186. Hawkey CJ. COX-2 inhibitors. Lancet. 1999; 353:307-14. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9929039?dopt=AbstractPlus

187. Kurumbail RG, Stevens AM, Gierse JK et al. Structural basis for selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 by anti-inflammatory agents. Nature. 1996; 384:644-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8967954?dopt=AbstractPlus

188. Riendeau D, Charleson S, Cromlish W et al. Comparison of the cyclooxygenase-1 inhibitory properties of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and selective COX-2 inhibitors, using sensitive microsomal and platelet assays. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997; 75:1088-95. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9365818?dopt=AbstractPlus

189. DeWitt DL, Bhattacharyya D, Lecomte M et al. The differential susceptibility of prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases-1 and -2 to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: aspirin derivatives as selective inhibitors. Med Chem Res. 1995; 5:325-43.