Oseltamivir (Monograph)

Brand name: Tamiflu

Drug class: Neuraminidase Inhibitors

- Sialic Acid Derivatives

VA class: AM800

Chemical name: [3R-(3α,4β,5α)]-ethyl 4-(acetylamino)-5-amino-3-(1-ethylpropoxy)-1-cyclohexene-1-carboxylate phosphate

Molecular formula: C16H28N2O4•H3PO4

CAS number: 204255-11-8

Introduction

Antiviral; neuraminidase inhibitor; sialic acid analog.1 2 3 4 5 6 9 64

Uses for Oseltamivir

Treatment of Seasonal Influenza A and B Virus Infections

Treatment of acute, uncomplicated illness caused by influenza A or B viruses in adults, adolescents, and pediatric patients ≥2 weeks of age.1 2 4 5 15 65 105 112 116 120 Although safety and efficacy not established in neonates <2 weeks of age† [off-label],1 also recommended when treatment of influenza considered necessary in this age group.112 120

For treatment of suspected or confirmed acute, uncomplicated seasonal influenza in otherwise healthy outpatients, CDC, IDSA, and others state that any age-appropriate influenza antiviral (oral oseltamivir, inhaled zanamivir, oral baloxavir marboxil, IV peramivir) can be used if not contraindicated.112 116 120 CDC states may consider early empiric antiviral treatment in outpatients with suspected influenza (e.g., influenza-like illness such as fever with either cough or sore throat) based on clinical judgement if such treatment can be initiated within 48 hours of illness onset.120

For treatment of suspected or confirmed seasonal influenza in hospitalized patients or outpatients with severe, complicated, or progressive illness (e.g., pneumonia, exacerbation of underlying chronic medical conditions), CDC states oseltamivir is the preferred influenza antiviral because of the lack of data regarding use of other influenza antivirals in such patients.120

Initiate treatment of seasonal influenza illness as soon as possible in all individuals with suspected or confirmed influenza who require hospitalization or have severe, complicated, or progressive illness (regardless of vaccination status or underlying illness).105 112 116 120 Early empiric antiviral treatment also recommended in individuals with suspected or confirmed influenza of any severity if they are at high risk of developing influenza-related complications because of age or underlying medical conditions (regardless of vaccination status).105 112 120 This includes children <2 years of age, adults ≥65 years of age, individuals of any age with certain chronic medical or immunosuppressive conditions, women who are pregnant women or up to 2 weeks postpartum, individuals <19 years of age receiving long-term aspirin therapy, American Indians, Alaskan natives, morbidly obese individuals with body mass index (BMI) ≥40, and residents of any age in nursing homes or other long-term care facilities.112 116 120

Although manufacturer states use for treatment of influenza only in patients who have been symptomatic for ≤48 hours,1 there is some evidence from observational studies of hospitalized patients that antiviral treatment might still be beneficial when initiated up to 4 or 5 days after illness onset.112 120 CDC, ACIP, and AAP recommend that antiviral treatment be initiated in all patients with severe, complicated, or progressive illness attributable to influenza and all hospitalized patients and patients at increased risk of influenza complications (either hospitalized or outpatient) who have suspected or confirmed influenza, even if it has been >48 hours after illness onset.112 120 Base decisions regarding use of empiric antiviral treatment in outpatients, especially high-risk patients, on disease severity and progression, age, underlying medical conditions, likelihood of influenza, and time since onset of symptoms.120

Consider that influenza and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have overlapping signs and symptoms and coinfection with influenza A or B viruses and SARS-CoV-2 can occur.120 Although laboratory testing can help distinguish between influenza virus infection and SARS-CoV-2 infection, CDC recommends initiating empiric influenza treatment in patients with suspected influenza who are hospitalized, have severe, complicated, or progressive illness, or are at high risk for influenza complication without waiting for results of influenza testing, SARS-CoV-2 testing, or multiplex molecular assays that detect influenza A and B viruses and SARS-CoV- 2.120

Consider viral surveillance data available from local and state health departments and CDC when selecting an antiviral for treatment of seasonal influenza.112 116 120 Strains of circulating influenza viruses and the antiviral susceptibility of these strains constantly evolve, and emergence of resistant strains may decrease effectiveness of influenza antivirals.1 120 Although circulating influenza A and B viruses during recent years generally have been susceptible to oseltamivir,120 195 198 199 200 201 202 consult most recent information on susceptibility of circulating viruses when selecting an antiviral for treatment of influenza.120

CDC issues recommendations concerning use of antiviral for treatment of influenza, and these recommendations are updated as needed during each influenza season.120 Information regarding influenza surveillance and updated recommendations for treatment of seasonal influenza are available from CDC at [Web].

Prevention of Seasonal Influenza A and B Virus Infections

Prevention of illness caused by seasonal influenza A or B viruses in adults, adolescents, and children ≥1 year of age.1 16 30 105 112 116

Annual vaccination with seasonal influenza virus vaccine, as recommended by CDC's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), is the primary means of preventing seasonal influenza and its severe complications.105 112 116 120 166 Prophylaxis with an appropriate antiviral active against circulating influenza strains is considered an adjunct to vaccination for control and prevention of influenza in certain individuals.1 105 112 116 120 166

Base decisions regarding use of antivirals for prophylaxis of seasonal influenza on the risk of influenza-related complications in the exposed individual, vaccination status, type and duration of contact, recommendations from local or public health authorities, and clinical judgment.112 120 In general, use antiviral postexposure prophylaxis only if it can be initiated within 48 hours after most recent exposure.112 116 120

CDC and others do not recommend routine use of influenza antivirals for postexposure prophylaxis of seasonal influenza in exposed individuals; may consider such prophylaxis in certain situations in exposed individuals at high risk for influenza-related complications for whom influenza vaccine is contraindicated, unavailable, or expected to have low efficacy (e.g., immunocompromised individuals).116 120 Other possible candidates for antiviral prophylaxis include unvaccinated health care personnel, public health workers, and first responders with unprotected, close-contact exposure to a patient with confirmed, probable, or suspected influenza during the time when the patient was infectious.112 120 Also may be considered for controlling influenza outbreaks in nursing and long-term care facilities or other closed or semi-closed settings with large numbers of individuals at high risk for influenza-related complications.112 120

CDC issues recommendations concerning use of antivirals for prophylaxis of influenza, and these recommendations are updated as needed during each influenza season.120 Information regarding influenza surveillance and updated recommendations for prevention of seasonal influenza are available from CDC at [Web].

Avian Influenza A Virus Infections

Treatment or prevention of infections caused by avian influenza A viruses† [off-label] (e.g., H5N1, H7N3, H7N7, H7N9).46 47 50 61 68 94 104 152 169 178 179 180 187

For treatment of uncomplicated avian influenza A infections in outpatients, CDC states that oral oseltamivir, inhaled zanamivir, or IV peramivir may be used.178

For treatment of severe, complicated, or progressive avian influenza A infections in hospitalized patients or outpatients, including infections caused by avian influenza A (H7N9), avian influenza A (H5N1), or novel avian influenza A H5 viruses, CDC recommends oseltamivir as antiviral of choice.178 In those with severe avian influenza A infection who cannot tolerate or absorb oseltamivir administered orally or enterically (e.g., because of suspected or known gastric stasis, malabsorption, or GI bleeding), CDC states use of IV peramivir may be considered.178 Inhaled zanamivir not recommended because data insufficient regarding use for treatment of severe influenza in hospitalized patients or outpatients.178

When antiviral prophylaxis indicated in close contacts of individuals with confirmed or probable infection with avian influenza A viruses that have caused or potentially may cause severe disease or indicated in individuals who have been exposed to birds infected with such avian influenza A viruses, CDC recommends oral oseltamivir or inhaled zanamivir.179 180

Information regarding treatment and prevention of avian influenza A infections is available from CDC at [Web] and WHO at [Web].

Variant Influenza Virus Infections

Treatment of infections cause by variant influenza viruses† [off-label].196

Influenza viruses that circulate in swine are called swine influenza viruses when isolated from swine, but are called variant influenza viruses when isolated from humans.194 196 Influenza A (H1N1) variant (H1N1v), influenza A (H1N2) variant (H1N2v), and influenza A (H3N2) variant (H3N2v) infections reported in US.194 196 Limited data to date indicate variant influenza viruses are susceptible to neuraminidase inhibitor antivirals (oseltamivir, peramivir, zanamivir).196

CDC states management of infections caused by variant influenza viruses is similar to management of seasonal influenza virus infections.196 Early initiation of oseltamivir recommended by CDC for treatment of hospitalized patients, those with severe and progressive illness, and any high-risk patient with suspected or confirmed variant influenza virus infection.196 Antiviral treatment with a neuraminidase inhibitor also recommended for outpatients with suspected influenza, including variant influenza virus infection, if individual considered at high risk for influenza complications.196 Antiviral treatment can be considered for any previously healthy, symptomatic outpatient not at high risk who has confirmed or suspected variant virus infection on the basis of clinical judgment, if treatment can be initiated ≤48 hours after illness onset.196

Information regarding variant influenza virus infections is available from CDC at [Web].

Pandemic Influenza

Treatment or prevention of pandemic influenza† [off-label] caused by susceptible strains of influenza virus.52 151

Influenza viruses can cause pandemics, during which rates of illness and death from influenza-related complications can increase dramatically worldwide.52 104 166

Most recent influenza pandemic occurred during 2009 and was related to a novel influenza A (H1N1) strain, influenza A (H1N1)pdm09.52 135 151 166 In the US, the pandemic was characterized by a substantial increase in influenza activity that peaked in late October and early November 2009 and returned to seasonal baseline levels by January 2010.123 166 During that time, ≥99% of influenza viruses circulating in the US were influenza A (H1N1)pdm09.123 166 After the pandemic, influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 became a seasonal influenza virus and continues to circulate with other seasonal viruses.135 195 198 199 200 201 202

The spread of the highly pathogenic H5N1 strain of avian influenza A in poultry in Asia and other countries that was first identified in 2003 represents a potential future pandemic threat.50 54 55 56 104 147 In addition, the novel avian influenza A (H7N9) virus that was first identified in China in March 2013 represents a potential future pandemic threat.50 104 182 (See Avian Influenza A Virus Infections under Uses.)

Information on pandemic influenza, including planning and preparedness resources if an influenza pandemic occurs, is available from CDC at [Web] and WHO at [Web].

Related/similar drugs

Tamiflu, amantadine, Vicks DayQuil Severe Cold & Flu, Xofluza, Coricidin HBP Cold & Flu, Afluria, Tylenol Cold & Flu Severe

Oseltamivir Dosage and Administration

Administration

Oral Administration

Administer orally without regard to meals;1 administration with meals may improve GI tolerability.1

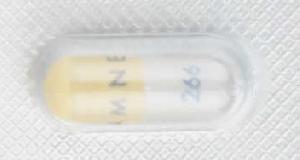

Commercially available as 30-, 45-, and 75-mg capsules and as a powder for oral suspension that is reconstituted to provide an oral suspension containing 6 mg/mL.1

Reconstituted oseltamivir oral suspension is the preferred preparation for individuals unable to swallow capsules.1 Alternatively, if the oral suspension not available from the manufacturer or wholesaler, the appropriate dosage can be administered by opening the appropriate strength of commercially available capsules and mixing the contents with a sweet liquid (e.g., regular or sugar-free chocolate syrup, corn syrup, caramel topping, light brown sugar dissolved in water).1 141

During emergency situations if the powder for oral suspension not available and the appropriate strength of oseltamivir capsules not available to mix with sweetened liquids, a pharmacist can prepare an emergency supply of extemporaneous oral suspension using 75-mg oseltamivir capsules and simple syrup, cherry syrup vehicle (Humco), or Ora-Sweet SF (Paddock).1 Consult manufacturer's information for specific instructions.1

Reconstitution

Reconstitute commercially available powder for oral suspension at the time of dispensing.1 Tap bottle to thoroughly loosen white powder and then add the amount of water specified on the bottle; shake well for 15 seconds.1

Reconstituted oral suspension contains 6 mg/mL; each 12.5 mL contains 75 mg of oseltamivir.1

Provide an oral dosing device that can accurately measure the appropriate volume in mL;1 counsel patient and/or caregiver how to use the oral dosing dispenser to correctly measure and administer the appropriate dose.1

Shake suspension well prior to each dose.1

Dosage

Available as oseltamivir phosphate; dosage expressed in terms of oseltamivir.1

Pediatric Patients

Treatment of Seasonal Influenza A and B Virus Infections

Oral

Initiate treatment as soon as possible (preferably within 48 hours of symptom onset).1 112 120 Although efficacy only established when given within 48 hours after onset of symptoms,1 there is some evidence from hospitalized patients that antiviral treatment initiated up to 4 or 5 days after onset of symptoms may still be beneficial.112 116 120 (See Uses: Treatment of Seasonal Influenza A and B Virus Infections.)

Recommended duration of antiviral treatment is 5 days,1 112 120 but hospitalized patients with severe or prolonged infections or individuals with immunosuppression may require >5 days of treatment.116 120

Infants 2 weeks to <1 year of age: 3 mg/kg twice daily for 5 days recommended by manufacturer.1

Neonates and infants <1 year of age: AAP recommends 3.5 mg/kg twice daily for 5 days in infants 9 through 11 months of age and 3 mg/kg twice daily for 5 days in full-term neonates and infants through 8 months of age.112 Although safety and efficacy not established in neonates <2 weeks of age† [off-label],1 AAP states the drug can be used for treatment of influenza in neonates from birth† because of its known safety profile.112 (See Pediatric Use under Cautions.)

Dosage recommended for full-term infants may be excessive in preterm neonates.112 120 Limited data suggest that, if the drug is considered necessary for treatment of influenza in preterm neonates†, dosage should be based on postmenstrual age (i.e., gestational age plus chronological age).112 120 AAP and CDC recommend 1 mg/kg twice daily in preterm neonates with postmenstrual age <38 weeks, 1.5 mg/kg twice daily in those with postmenstrual age of 38 through 40 weeks, and 3 mg/kg twice daily in those with postmenstrual age >40 weeks.112 120 Consult pediatric infectious disease expert if treatment of influenza considered necessary in extremely premature neonates (postmenstrual age <28 weeks).112

Children 1–12 years of age: Dosage is based on weight.1 (See Table 1.)

Adolescents ≥13 years of age: 75 mg twice daily for 5 days.1 Each dose can be given as single 75-mg capsule or 12.5 mL of oral suspension containing 6 mg/mL.1

|

Weight (kg) |

Daily Dosage (mg) |

Daily Dosage (Volume of Reconstituted Oral Suspension Containing 6 mg/mL) |

Daily Dosage (Capsules) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

≤15 |

30 mg twice daily for 5 days |

5 mL twice daily for 5 days |

One 30-mg capsule twice daily for 5 days |

|

15.1–23 |

45 mg twice daily for 5 days |

7.5 mL twice daily for 5 days |

One 45-mg capsule twice daily for 5 days |

|

23.1–40 |

60 mg twice daily for 5 days |

10 mL twice daily for 5 days |

Two 30-mg capsules twice daily for 5 days |

|

≥40.1 |

75 mg twice daily for 5 days |

12.5 mL twice daily for 5 days |

One 75-mg capsule twice daily for 5 days |

Prevention of Seasonal Influenza A and B Virus Infections

Oral

Initiate prophylaxis within 48 hours after exposure (e.g., close contact with infected individual).1 Protection lasts as long as the drug is continued.1

Manufacturer states prophylaxis should be continued for ≥10 days after last exposure in close contact of exposed individuals; during community outbreaks, manufacturer states prophylaxis may be continued for up to 6 weeks in immunocompetent individuals and for up to 12 weeks in immunocompromised individuals.1

CDC recommends a duration of 7 days after last known exposure.120 In institutional settings (e.g., long-term care facilities for elderly individuals and children), CDC recommends antiviral prophylaxis be given for minimum of 2 weeks and continued for up to 1 week after last known case of influenza is identified.120

Although safety and efficacy not established for prophylaxis of influenza in infants <1 year of age†,1 CDC states infants 3 months to <1 year of age† can receive 3 mg/kg once daily for 7 days if considered necessary.120 AAP recommends 3.5 mg/kg once daily for 10 days in infants 9 through 11 months of age† and 3 mg/kg once daily for 10 days in infants 3 through 8 months of age†.112

Because of limited safety and efficacy data, CDC and AAP do not recommend use for prophylaxis of influenza in full-term or premature infants <3 months of age† unless situation is judged critical.112 120

Children 1–12 years of age: Dosage is based on weight.1 (See Table 2.)

Adolescents ≥13 years of age: 75 mg once daily.1

Manufacturer states continue prophylaxis in pediatric patients for 10 days following close contact with infected individual;1 during community outbreaks, manufacturer states may continue prophylaxis for up to 6 weeks in immunocompetent individuals and for up to 12 weeks in immunocompromised individuals.1

|

Weight (kg) |

Daily Dosage (mg) |

Daily Dosage (Volume of Reconstituted Oral Suspension Containing 6 mg/mL) |

Daily Dosage (Capsules) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

≤15 |

30 mg once daily for 10 days |

5 mL once daily for 10 days |

One 30-mg capsule once daily for 10 days |

|

15.1–23 |

45 mg once daily for 10 days |

7.5 mL once daily for 10 days |

One 45-mg capsule once daily for 10 days |

|

23.1–40 |

60 mg once daily for 10 days |

10 mL once daily for 10 days |

Two 30-mg capsules once daily for 10 days |

|

≥40.1 |

75 mg once daily for 10 days |

12.5 mL once daily for 10 days |

One 75-mg capsule once daily for 10 days |

Avian Influenza A Virus Infection

Treatment of Avian Influenza A Virus Infections†

OralOptimum dosage and duration of treatment unknown, especially for severe or complicated infections.50 63 68 104 178

Dosage usually recommended for treatment of seasonal influenza A and B virus infections has been recommended.63 104 178 (See Treatment of Seasonal Influenza A and B Virus Infections under Dosage and Administration.) Although some experts suggest a higher dosage be considered for severely ill or immunocompromised patients,50 63 68 85 104 limited data from patients with severe influenza, including some with avian influenza A (H1N1) infection, suggest that higher dosage may not provide additional clinical benefit.112 120 178

Although 5 days of treatment may be adequate for uncomplicated illness, consider longer duration of treatment (i.e., 7–10 days) in severely ill hospitalized patients and immunosuppressed individuals.50 63 68 85 104 178

Initiate treatment as early as possible.50 104 152 178 May be most beneficial if initiated within 2 days of symptom onset,152 but is warranted even if initiated >48 hours after illness onset or in patients who present for care in later stages of illness.50 104 152 178

Prevention of Avian Influenza A Virus Infections†

OralProphylaxis in close contacts of individuals with confirmed or probable infection or individuals exposed to infected birds: CDC and WHO state that the twice-daily dosage usually recommended for treatment of seasonal influenza A and B virus infections can be used.50 94 179 180 (See Treatment of Seasonal Influenza A and B Virus Infections under Dosage and Administration.)

Continue antiviral prophylaxis for 5–10 days after last known exposure.50 94 180 If exposure was time-limited and not ongoing, continue for 5 days after last known exposure.179 180

Adults

Treatment of Seasonal Influenza A and B Virus Infections

Oral

75 mg twice daily for 5 days.1

Initiate treatment as soon as possible (preferably within 48 hours of symptom onset).1 112 120 Although efficacy only established when given within 2 days after onset of symptoms,1 there is some evidence from hospitalized patients that antiviral treatment initiated up to 4 or 5 days after onset of symptoms may still be beneficial.112 116 120 144 (See Uses: Treatment of Seasonal Influenza A and B Virus Infections.)

Recommended duration of antiviral treatment is 5 days, but hospitalized patients with severe or prolonged infections or individuals with immunosuppression may require >5 days of treatment.120

Prevention of Seasonal Influenza A and B Virus Infections

Oral

75 mg once daily.1

Initiate prophylaxis within 48 hours after exposure (e.g., close contact with infected individual).1 Protection lasts as long as the drug is continued.1

Manufacturer states prophylaxis should be continued for ≥10 days after last exposure in close contact of exposed individuals; during community outbreaks, manufacturer states prophylaxis may be continued for up to 6 weeks in immunocompetent individuals and for up to 12 weeks in immunocompromised individuals.1

CDC recommends a duration of 7 days after last known exposure.120 In institutional settings (e.g., long-term care facilities for elderly individuals and children), CDC recommends antiviral prophylaxis be given for minimum of 2 weeks and continued for up to 1 week after last known case of influenza is identified.120

Avian Influenza A Virus Infections

Treatment of Avian Influenza A Virus Infections†

OralOptimum dosage and duration of treatment unknown, especially for severe or complicated infections.50 63 68 104 178

Dosage usually recommended for treatment of seasonal influenza A and B virus infections has been recommended.63 104 178 (See Treatment of Seasonal Influenza A and B Virus Infections under Dosage and Administration.) Although some experts suggest a higher dosage (e.g., 150 mg twice daily in adults with normal renal function) be considered for severely ill or immunocompromised patients,50 63 68 85 104 limited data from those with severe influenza, including some with avian influenza A (H1N1) infection, suggest that higher dosage may not provide additional clinical benefit.112 120 178

Although 5 days may be adequate for uncomplicated illness, consider longer duration of treatment (i.e., 7–10 days) in severely ill hospitalized patients and immunosuppressed individuals.50 63 68 85 104 178

Initiate treatment as early as possible.50 104 152 178 May be most beneficial if initiated within 2 days of symptom onset,152 but is warranted even if initiated >48 hours after illness onset or in patients who present for care in the later stages of illness.50 104 152 178

Prevention of Avian Influenza A Virus Infections†

OralProphylaxis in close contacts of individuals with confirmed or probable infection or individuals exposed to infected birds: CDC and WHO state that the twice-daily dosage usually recommended for treatment of seasonal influenza A and B virus infections can be used.50 94 179 180 (See Treatment of Seasonal Influenza A and B Virus Infections under Dosage and Administration.)

Continue antiviral prophylaxis for 5–10 days after last known exposure.50 94 180 If exposure was time-limited and not ongoing, continue for 5 days after last known exposure.179 180

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

Usual dosage can be used in patients with mild to moderate hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score ≤9).1 42 Safety and pharmacokinetics not evaluated in those with severe hepatic impairment.1

Renal Impairment

Adjust dosage in adults with Clcr 10–60 mL/minute and in those with end-stage renal disease (ESRD; Clcr ≤10 mL/minute) undergoing hemodialysis or continuous peritoneal dialysis.1 120 (See Table 3 and Table 4.)

Not recommended in adults with ESRD who are not undergoing dialysis.1 120

Dosage recommendations not available for pediatric patients with renal impairment; CDC states dosage recommendations for adults with renal impairment may be useful for treatment or prevention of influenza in children with renal impairment who weigh >40 kg.120

Dosage assumes 3 hemodialysis sessions in the 5-day period.120 If influenza symptoms developed during the 48 hours between hemodialysis sessions, give initial oseltamivir dose immediately and give the post-hemodialysis dose regardless of when initial dose was given.1 120

Data derived from studies in patients undergoing CAPD.1 120

|

Clcr (mL/minute) |

Dosage |

|---|---|

|

>30 to 60 |

30 mg twice daily for 5 days |

|

>10 to 30 |

30 mg once daily for 5 days |

|

≤10 (ESRD receiving hemodialysis) |

30 mg given immediately and then 30 mg after each hemodialysis cycle for maximum of 5 days |

|

≤10 (ESRD receiving continuous peritoneal dialysis) |

Single 30-mg dose given immediately |

|

ESRD not receiving dialysis |

Not recommended |

Manufacturer states prophylaxis during community outbreaks may be continued for up to 6 weeks in immunocompetent individuals and up to 12 weeks in immunocompromised individuals.1

Data derived from studies in patients undergoing CAPD.1 120

|

Clcr (mL/minute) |

Dosage |

|---|---|

|

>30 to 60 |

30 mg once daily for ≥10 days |

|

>10 to 30 |

30 mg once every other day for ≥10 days |

|

≤10 (ESRD receiving hemodialysis) |

30 mg given immediately and then 30 mg after alternate hemodialysis cycles |

|

≤10 (ESRD receiving continuous peritoneal dialysis) |

30 mg given immediately and then 30 mg once weekly |

|

ESRD not receiving dialysis |

Not recommended |

Geriatric Patients

Dosage adjustments not needed except those related to renal impairment.1

Cautions for Oseltamivir

Contraindications

-

Known hypersensitivity to oseltamivir or any ingredient in the formulations.1

Warnings/Precautions

Sensitivity Reactions

Dermatologic and Hypersensitivity Reactions

Anaphylaxis and serious skin reactions, including toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme, reported.1

Rash, swelling of the face or tongue, allergy, dermatitis, eczema, or urticaria reported during postmarketing experience.1

If an allergic reaction occurs or is suspected, discontinue oseltamivir and institute appropriate therapy.1

Neuropsychiatric Events

Adverse neuropsychiatric events (e.g., agitation, anxiety, self-injury, delirium, hallucinations, altered level of consciousness, confusion, nightmares, delusions, abnormal behavior, seizures) and death reported.1 84 88 Cases generally had an abrupt onset and rapid resolution.1 Role of oseltamivir not determined.1 (See Pediatric Use under Cautions.)

Influenza itself can be associated with neurologic and behavioral symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, delirium, abnormal behavior) and fatalities can occur.1 Although such events may occur in the setting of encephalitis or encephalopathy, they can occur without obvious severe disease.1

Closely monitor patients with influenza for signs of abnormal behavior.1 If neuropsychiatric symptoms develop, consider risks versus benefits of continued therapy.1

Bacterial Infections

Serious bacterial infections may begin with influenza-like symptoms or may coexist with or occur as complications of influenza.1 No evidence that oseltamivir prevents such complications.1

No evidence of efficacy in illness caused by any organisms other than influenza viruses.1

Consider potential for secondary bacterial infections; if such infections occur, treat appropriately.1

Immunocompromised Individuals

Although efficacy for treatment or prevention of influenza not established in immunocompromised patients,1 safety of oseltamivir prophylaxis has been demonstrated for up to 12 weeks in immunocompromised patients.1 Has been used for treatment or prevention of influenza in some immunocompromised individuals†, including bone marrow transplant (BMT) recipients, hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients, solid organ transplant recipients, and chemotherapy patients.1 74 75 101

Other Concomitant Illness

Efficacy for treatment of influenza in patients with chronic cardiac disease and/or underlying pulmonary disease not established; no evidence to date of increased risk of adverse effects in this population.1

No data available regarding use for treatment of influenza in patients with any medical condition severe or unstable enough to require inpatient care.1

Influenza Vaccination

Not a substitute for annual vaccination with a seasonal influenza vaccine (influenza virus vaccine inactivated, influenza vaccine recombinant, influenza vaccine live intranasal).1 112 120

Although antivirals used for treatment or prevention of influenza, including oseltamivir, may be used concomitantly with or at any time before or after influenza virus vaccine inactivated or influenza vaccine recombinant,1 100 134 influenza antivirals may inhibit the vaccine virus contained in influenza vaccine live intranasal and decrease efficacy of the live vaccine.1 100 (See Specific Drugs under Interactions.)

Sorbitol

When the commercially available oral suspension containing 6 mg/mL is used, each 75-mg dose of oseltamivir contains 2 g of sorbitol.1 This amount of sorbitol exceeds the maximum daily limit of sorbitol for individuals with hereditary fructose intolerance and may result in dyspepsia and diarrhea.1

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

No adequate and well-controlled studies using oseltamivir in pregnant women to inform a drug-associated risk of adverse developmental outcomes.1 Available published epidemiological data suggest that oseltamivir administered during any trimester of pregnancy is not associated with an increased risk of birth defects;1 however, these studies had various limitations (e.g., small sample sizes, use of different comparison groups, lack of information on dosage) which preclude a definitive assessment of the risk.1

In pregnant rats and rabbits, no adverse embryofetal effects observed when oral oseltamivir administered at dosages resulting in clinically relevant exposures.1

Pregnant women are at increased risk for severe complications from influenza,1 120 142 which may lead to adverse pregnancy and/or fetal outcomes including maternal death, still births, birth defects, preterm delivery, low birthweight, and small size for gestational age.1

Oseltamivir is the preferred antiviral for treatment of suspected or confirmed influenza or prevention of influenza in women who are pregnant or up to 2 weeks postpartum.120 142

Lactation

Distributed into human milk in low concentrations that are considered unlikely to cause toxicity in nursing infants.1

Consider benefits of breast-feeding and importance of oseltamivir to the woman; also consider potential adverse effects on breast-fed child from the drug or from underlying maternal condition.1

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy for treatment of influenza not established in infants <2 weeks of age.1

Safety and efficacy for prophylaxis of influenza not established in infants <1 year of age.1

Manufacturer states efficacy not established in pediatric patients with asthma.1

Young children, especially those <2 years of age, are at increased risk of influenza infection, hospitalization, and complications.112 120 During the 2009 influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 pandemic, FDA issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) that temporarily allowed use of oseltamivir for emergency treatment or prevention of these infections in infants <1 year of age†.121 150 Although the EUA expired in June 2010,150 AAP states that, because of the known safety profile of the drug, use for treatment of influenza in full-term or preterm neonates from birth† or for prevention of influenza in infants ≥3 months of age† is appropriate if indicated.112 CDC and AAP state that oseltamivir not recommended for prevention of influenza in infants <3 months of age† unless situation is judged critical.112 120 (See Pediatric Patients under Dosage and Administration.)

Unusual adverse neurologic and/or psychiatric effects (e.g., self-injury, delirium, hallucinations, mental confusion, abnormal behavior, seizures) and some deaths reported in pediatric patients receiving oseltamivir for treatment of influenza;1 83 84 88 reported principally in children in Japan.83 84 A relationship to oseltamivir difficult to assess because of concomitantly used drugs, comorbid conditions, and/or lack of adequate detail in reports.88 After reviewing available data, FDA stated that it was unable to conclude that a causal relationship exists between oseltamivir and the reported pediatric deaths.88

Geriatric Use

No overall differences in safety or efficacy compared with younger adults.1

Hepatic Impairment

Safety and pharmacokinetics not evaluated in patients with severe hepatic impairment.1

Renal Impairment

Decreased clearance;1 possible increased risk of adverse effects.1

Dosage adjustments recommended in adults with Clcr 10–60 mL/minute and adults with ESRD (Clcr ≤10 mL/minute) undergoing dialysis.1 Not recommended in adults with ESRD not undergoing dialysis.1 (See Renal Impairment under Dosage and Administration.)

Common Adverse Effects

GI effects (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain), headache, bronchitis, insomnia, vertigo.1 2 3 4

Drug Interactions

Oseltamivir phosphate and its active metabolite not metabolized by and do not inhibit CYP isoenzymes;1 25 drug interactions with drugs that are substrates or inhibitors of these enzymes unlikely.1

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Acetaminophen |

No clinically important pharmacokinetic interactions1 |

Dosage adjustments not needed1 |

|

Amantadine |

No clinically important pharmacokinetic interactions1 |

Dosage adjustments not needed1 |

|

Amoxicillin |

No clinically important pharmacokinetic interactions1 |

Dosage adjustments not needed1 |

|

Antacids (containing magnesium, aluminum, or calcium carbonate) |

Dosage adjustments not needed1 |

|

|

Aspirin |

Dosage adjustments not needed1 |

|

|

Cimetidine |

No clinically important pharmacokinetic interactions1 |

Dosage adjustments not needed1 |

|

Influenza vaccines |

Influenza virus vaccine inactivated (IV) or influenza vaccine recombinant (RIV): No specific studies, but oseltamivir unlikely to interfere with antibody response to the vaccines;1 100 134 oseltamivir does not interfere with humoral antibody response to influenza infection1 Influenza vaccine live intranasal (LAIV): No specific studies;1 100 oseltamivir may inhibit the vaccine virus and decrease efficacy of the live vaccine;1 100 120 134 oseltamivir may interfere with LAIV if given from 48 hours before through 2 weeks after the live vaccine100 120 |

IIV or RIV: May administer concomitantly with or any time before or after oseltamivir1 100 134 LAIV: Do not administer the live vaccine until ≥48 hours after oseltamivir discontinued;1 100 do not administer oseltamivir until ≥2 weeks after the vaccine;1 100 if oseltamivir given 48 hours before to 14 days after LAIV, ACIP recommends revaccination using age-appropriate IIV or RIV100 120 |

|

Peramivir |

No evidence of drug interactions when oral oseltamivir used concomitantly with IV peramivir176 |

|

|

Probenecid |

Increased systemic exposure to oseltamivir carboxylate because of decreased renal tubular secretion1 34 |

Not expected to be clinically important;1 dosage adjustments not needed1 |

|

Rimantadine |

No clinically important pharmacokinetic interactions1 |

Dosage adjustments not needed1 |

|

Warfarin |

No clinically important pharmacokinetic interactions1 |

Dosage adjustments not needed1 |

Oseltamivir Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Oseltamivir phosphate readily absorbed following oral administration and then extensively converted to the active metabolite (oseltamivir carboxylate).1 24 25

Absolute bioavailability of oseltamivir carboxylate 80% following oral administration of oseltamivir phosphate;25 peak concentrations of active metabolite attained within 3–4 hours.1

Food

Administration of oseltamivir phosphate with food has no effect on peak plasma concentrations or AUC of oseltamivir carboxylate.1

Distribution

Extent

Following oral administration of oseltamivir phosphate, oseltamivir carboxylate distributed throughout body, including upper and lower respiratory tract.24 25

Placental transfer of oseltamivir carboxylate demonstrated in rats and rabbits; not known whether oseltamivir or oseltamivir carboxylate crosses the placenta in humans.1

Oseltamivir and oseltamivir carboxylate are distributed into milk.1

Plasma Protein Binding

Oseltamivir phosphate 42% bound to plasma proteins; oseltamivir carboxylate 3% bound to plasma proteins.1 24

Elimination

Metabolism

Oseltamivir phosphate extensively (>90%) converted to oseltamivir carboxylate, principally by hepatic esterases.1 No further metabolism of oseltamivir carboxylate occurs.1

Oseltamivir phosphate and oseltamivir carboxylate not metabolized by CYP enzymes.1 25

Elimination Route

Oseltamivir carboxylate eliminated (>99%) by renal excretion;1 24 25 <20% of dose eliminated in feces.1

Half-life

Plasma half-life of oseltamivir phosphate is 1–3 hours;1 24 half-life of oseltamivir carboxylate is 6–10 hours.1 25

Special Populations

Renal impairment: Systemic exposure to oseltamivir carboxylate increases with declining renal function.1 In patients undergoing CAPD, peak concentrations following a single 30-mg dose of oseltamivir or once-weekly oseltamivir was approximately threefold higher than peak concentrations in patients with normal renal function receiving 75 mg twice daily.1

Mild or moderate hepatic impairment: Systemic exposure to oseltamivir carboxylate is comparable to that in individuals without hepatic impairment.1 42

Pediatric patients: Clearance of both oseltamivir phosphate and oseltamivir carboxylate increased in younger pediatric patients compared with adults.1 Total clearance of oseltamivir carboxylate decreases linearly with increasing age (up to 12 years of age);1 pharmacokinetics in those >12 years of age similar to adults.1

Geriatric patients: Exposure to oseltamivir carboxylate at steady state approximately 25–35% higher in those 65–78 years of age compared with younger adults;1 3 half-lives in geriatric individuals are similar to those in younger adults.1

Stability

Storage

Oral

Capsules

25°C (may be exposed to 15–30°C).1

Powder for Suspension

25°C (may be exposed to 15–30°C).1

Following reconstitution, store suspension at 2–8°C for up to 17 days.1 Alternatively, may be stored for up to 10 days at 25°C (may be exposed to 15–30°).1 Do not freeze.1

Extemporaneous Oral Suspension

Extemporaneous oral suspensions prepared according to manufacturer's directions using 75-mg oseltamivir capsules and simple syrup, cherry syrup vehicle, or Ora-Sweet SF are stable for 5 weeks at 2–8°C or 5 days at 25°C.1

Actions and Spectrum

-

Oseltamivir phosphate is prodrug and is inactive until hydrolyzed by hepatic esterases to oseltamivir carboxylate, the active metabolite.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

-

Oseltamivir carboxylate is a potent selective competitive inhibitor of influenza virus neuraminidase, an enzyme essential for viral replication;1 2 3 8 9 possibly alters virus particle aggregation and release.1

-

Active in vitro in cell culture against influenza A and B viruses.1 2 3 7 8 Majority of seasonal influenza A (H1N1)pdm09, influenza A (H3N2), and influenza B viruses circulating during recent influenza seasons have been susceptible to oseltamivir in vitro.120 144 163 188 189 192 193 194 195 196 198

-

Active in vitro against some avian influenza A (H5N1) and other avian influenza A viruses (e.g., H7N2, H7N9, H9N2, H10N8).26 27 50 58 61 104 168 171

-

Major mechanisms of resistance to neuraminidase inhibitors are viral neuraminidase (NA) mutations that affect ability of the drugs to inhibit the enzyme and hemagglutinin (HA) mutations that reduce viral dependence on neuraminidase activity.1

-

Resistance to oseltamivir has been produced in vitro by serial passage of influenza A and B viruses in cell culture in the presence of increasing concentrations of oseltamivir carboxylate and reduced in vitro susceptibility have been observed in clinical isolates.1 4 36 43 Viral surveillance data from recent influenza seasons indicate that reduced in vitro susceptibility or resistance to oseltamivir was reported rarely in circulating strains of influenza A (H1N1)pdm09, influenza A (H3N2), influenza B (Yamagata lineage), and influenza B (Victoria lineage).195 198 199 200 201 202

-

Avian influenza A (H5N1)50 68 73 81 104 168 and avian influenza A (H7N9)169 170 197 with reduced in vitro susceptibility or resistance to oseltamivir reported.

-

Cross-resistance between oseltamivir and other neuraminidase inhibitors (e.g., peramivir, zanamivir) reported in influenza A and B viruses.1 9 36 37 38 43 62 172 173 175 176 However, because oseltamivir, peramivir, and zanamivir bind to different sites on the neuraminidase enzyme or interact differently with binding sites, cross-resistance among the drugs is variable.9 36 37 43 62 173 175

Advice to Patients

-

Importance of using the appropriate graduated oral dosing dispenser to measure and administer dose of reconstituted oral suspension.1

-

Importance of initiating oseltamivir treatment as soon as possible after appearance of influenza symptoms (within 48 hours after symptom onset);1 efficacy not established if treatment begins >48 hours after symptoms have been established.1

-

Importance of initiating oseltamivir prophylaxis as soon as possible after exposure to influenza (within 48 hours after exposure).1

-

Importance of complying with the entire drug regimen.1 Importance of taking missed dose as soon as remembered, except if within 2 hours of the next scheduled dose.1

-

Advise patients and/or caregivers of the risk of severe allergic reactions (including anaphylaxis) or serious skin reactions.1 Instruct patients and/or caregiver to discontinue oseltamivir and seek immediate medical attention if an allergic-like reaction occurs or is suspected.1

-

Advise patients and/or caregivers of risk of neuropsychiatric events;1 importance of informing clinician if signs of unusual behavior develop.1

-

Inform patients with hereditary fructose intolerance that a 75-mg dose of oseltamivir oral suspension delivers 2 g of sorbitol;1 this is above the daily maximum limit of sorbitol and may cause dyspepsia and diarrhea.1

-

Advise patients that oseltamivir is not a substitute for annual vaccination with influenza virus vaccine.1

-

Importance of informing clinicians of existing or contemplated therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs, as well as any concomitant illnesses.1

-

Importance of women informing clinicians if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1

-

Importance of advising patients of other important precautionary information.1 (See Cautions.)

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Capsules |

30 mg (of oseltamivir)* |

Oseltamivir Capsules |

|

|

Tamiflu |

Genentech |

|||

|

45 mg (of oseltamivir)* |

Oseltamivir Capsules |

|||

|

Tamiflu |

Genentech |

|||

|

75 mg (of oseltamivir)* |

Oseltamivir Capsules |

|||

|

Tamiflu |

Genentech |

|||

|

For suspension |

6 mg (of oseltamivir) per mL* |

Oseltamivir for Suspension |

||

|

Tamiflu |

Genentech |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2024, Selected Revisions October 4, 2021. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

1. Genentech, Inc. Tamiflu (oseltamivir phosphate) capsules and for oral suspension prescribing information. South San Francisco, CA: 2019 Aug.

2. Hayden FG, Treanor JJ, Fritz RS et al. Use of the oral neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir in experimental human influenza: randomized controlled trials for prevention and treatment. JAMA. 1999; 282:1240-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10517426?dopt=AbstractPlus

3. Hayden FG, Atmar RL, Schilling M et al. Use of the selective oral neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir to prevent influenza. N Engl J Med. 1999; 341:1336-43. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10536125?dopt=AbstractPlus

4. Treanor JJ, Hayden FG, Vrooman PS et al for the US Oral Neuraminidase Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the oral neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir in treating acute influenza: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000; 283:1016-24. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10697061?dopt=AbstractPlus

5. Nicholson KG, Aoki FY, Osterhaus ADME et al on behalf of the Neuraminidase Inhibitor Flu Treatment Investigator Group. Efficacy and safety of oseltamivir in treatment of acute influenza: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2000; 355:1845-50. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10866439?dopt=AbstractPlus

6. Kim CU, Chen X, Mendel DB. Neuraminidase inhibitors as anti-influenza virus agents. Antivir Chem Chemother. 1999; 10:141-54. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10480735?dopt=AbstractPlus

7. Cox NJ, Hughes JM. New options for the prevention of influenza. N Engl J Med. 1999; 341:1387-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10536132?dopt=AbstractPlus

8. Sidwell RW, Huffman JH, Barnard DL et al. Inhibition of influenza virus infections in mice by GS4104, an orally effective influenza virus neuraminidase inhibitor. Antiviral Res. 1998; 37:107-20. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9588843?dopt=AbstractPlus

9. Calfee DP, Hayden FG. New approaches to influenza chemotherapy: neuraminidase inhibitors. Drugs. 1998; 45:537-53.

12. Roche, Nutley, NJ: Personal communication.

15. Whitley RJ, Hayden FG, Reisinger KS et al. Oral oseltamivir treatment of influenza in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001; 20:127-33. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11224828?dopt=AbstractPlus

16. Welliver R, Monto AS, Carewicz O et al for the Oseltamivir Post Exposure Prophylaxis Investigator Group. Effectiveness of oseltamivir in preventing influenza in household contacts: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001; 285:748-54. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11176912?dopt=AbstractPlus

22. Kaiser L, Wat C, Mills T et al. Impact of oseltamivir treatment on influenza-related lower respiratory tract complications and hospitalizations. Arch Intern Med. 2003; 163:1667-72. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12885681?dopt=AbstractPlus

24. Doucette KE, Aoki FY. Oseltamivir: a clinical and pharmacological perspective. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2001; 2:1671-83. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11825310?dopt=AbstractPlus

25. He G, Massarella J, Ward P. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the prodrug oseltamivir and its active metabolite Ro 64-0802. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999; 37:471-84. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10628898?dopt=AbstractPlus

26. Govorkova EA, Leneva IA, Goloubeva OG et al. Comparison of efficacies of RWJ-270201, zanamivir, and oseltamivir against H5N1, H9N2, and other avian influenza viruses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001; 45:2723-32. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=90723&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11557461?dopt=AbstractPlus

27. Leneva IA, Roberts N, Govorkova EA et al. The neuraminidase inhibitor GS4104 (oseltamivir phosphate) is efficacious against A/Hong Kong/156/97 (H5N1) and A/Hong Kong/1074/99 (H9N2) influenza viruses. Antiviral Res. 2000; 48:101-15. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11114412?dopt=AbstractPlus

28. Johnston SL, Ferrero F, Garcia ML et al. Oral oseltamivir improves pulmonary function and reduces exacerbation frequency for influenza-infected children with asthma. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005; 24:225-32.

29. Peters PH Jr, Gravenstein S, Norwood P et al. Long-term use of oseltamivir for the prophylaxis of influenza in a vaccinated frail older population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001; 49:1025-31. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11555062?dopt=AbstractPlus

30. Hayden FG, Belshe R, Villanueva C et al. Management of influenza in households: a prospective, randomized comparison of oseltamivir treatment with or without postexposure prophylaxis. J Infect Dis. 2004; 189:440-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14745701?dopt=AbstractPlus

31. Monto AS, Rotthoff J, Teich E et al. Detection and control of influenza outbreaks in well-vaccinated nursing home populations. Clin Infect Dis. 2004; 39:459-64. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15356805?dopt=AbstractPlus

33. Oo C, Barrett J, Dorr A et al. Lack of pharmacokinetic interaction between the oral anti-influenza prodrug oseltamivir and aspirin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002; 46:1993-5. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=127254&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12019123?dopt=AbstractPlus

34. Hill G, Cihlar T, Oo C et al. The anti-influenza drug oseltamivir exhibits low potential to induce pharmacokinetic drug interactions via renal secretion—correlation of in vivo and in vitro studies. Drug Metab Disp. 2002; 30:13-9.

35. Hayden FG. Pandemic influenza: is an antiviral response realistic? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004; 23(Suppl):S262-9.

36. McKimm-Breschkin J, Trivedi T, Hampson A et al. Neuraminidase sequence analysis and susceptibilities of influenza virus clinical isolates to zanamivir and oseltamivir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003; 47:2264-72.

37. Gubareva LV, Kaiser L, Matrosovich MN et al. Selection of influenza virus mutants in experimentally infected volunteers treated with oseltamivir. J Infect Dis. 2001; 183:523-31. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11170976?dopt=AbstractPlus

38. Gubareva LV, Webster RG, Hayden FG. Comparison of the activities of zanamivir, oseltamivir, and RWJ-270201 against clinical isolates of influenza virus and neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant variants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001; 45:3403-8. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=90844&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11709315?dopt=AbstractPlus

39. Oo C, Barrett J, Hill G et al. Pharmacokinetics and dosage recommendations for an oseltamivir oral suspension for the treatment of influenza in children. Paediatr Drugs. 2001; 3:229-36. (Erratum in Paediatr Drugs. 2001; 3:246.) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11310719?dopt=AbstractPlus

40. Oo C, Hill G, Dorr A et al. Pharmacokinetics of anti-influenza prodrug oseltamivir in children aged 1–5 years. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003; 59:411-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12910331?dopt=AbstractPlus

42. Snell P, Dave N, Wilson K et al. Lack of effect of moderate hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of oral oseltamivir and its metabolite oseltamivir carboxylate. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005; 59:598-601. (Erratum in Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005; 60:115.) http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1884852&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15842560?dopt=AbstractPlus

43. Ward P, Small I, Smith J et al. Oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and its potential for use in the event of an influenza pandemic. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005; 55(Suppl S1):i5-21. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15709056?dopt=AbstractPlus

44. Wetherall NT, Trivedi T, Zeller J et al. Evaluation of neuraminidase enzyme assays using different substrates to measure susceptibility of influenza virus clinical isolates to neuraminidase inhibitors: report of the neuraminidase inhibitor susceptibility network. J Clin Microbiol. 2003; 41:742-50. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=149673&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12574276?dopt=AbstractPlus

46. Hien TT, Liem NT, Dung NT et al. Avian influenza A (H5N1) in 10 patients in Vietnam. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350:1179-88. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14985470?dopt=AbstractPlus

47. Chokephaibulkit K, Uiprasertkul M, Puthavathana P et al. A child with avian influenza A (H5N1) infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005; 24:162-6.

50. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Information on avian influenza. From CDC website. Accessed 2021 Sep 3. http://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/index.htm

52. World Health Organization. WHO guidelines for pharmacological management of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 and other influenza viruses. Revised February 2010. Part I. Recommendations. From WHO website. Accessed 2014 Feb 4. http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/h1n1_guidelines_pharmaceutical_mngt.pdf

54. Longini IM Jr, Nizam A, Xu S et al. Containing pandemic influenza at the source. Sciencexpress. 2005 Aug 3.

55. Tsang KWT, Eng P, Liam CK et al. H5N1 influenza pandemic: contingency plans. Lancet. 2005; 366:533-4. Editorial. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16099278?dopt=AbstractPlus

56. Ferguson NM, Cummings DAT, Cauchemez S et al. Strategies for containing an emerging influenza pandemic in Southeast Asia. Nature. Published online at Nature.com on 3 August 2005. http://www.nature.com

58. Yen HL, Monto AS, Webster RG et al. Virulence may determine the necessary duration and dosage of oseltamivir treatment for highly pathogenic A/Vietnam/1203/04 influenza virus in mice. J Infect Dis. 2005; 192:665-72. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16028136?dopt=AbstractPlus

61. Koopmans M, Wilbrink B, Conyn M et al. Transmission of H7N7 avian influenza A virus to human beings during a large outbreak in commercial poultry farms in the Netherlands. Lancet. 2004; 363:587-93. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14987882?dopt=AbstractPlus

62. Yen H-L, Herlocher LM, Hoffman E et al. Neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant influenza viruses may differ substantially in fitness and transmissibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005: 49: 4075-84.

63. Reviewers’ comments (personal observations).

64. Moscona A. Neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:1363-73. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16192481?dopt=AbstractPlus

65. Cooper NJ, Sutton AJ, Abrams KR et al. Effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in treatment and prevention of influenza A and B: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2003; 326:1235-40. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=161558&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12791735?dopt=AbstractPlus

66. Bowles SK, Lee W, Simor AE et al. Use of oseltamivir during influenza outbreaks in Ontario nursing homes, 1999-2000. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002; 50:608-16. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11982659?dopt=AbstractPlus

67. Nordstrom BL, Sung I, et al Suter P. Risk of pneumonia and other complications of influenza-like illness in patients treated with oseltamivir. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005; 21:761-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15969875?dopt=AbstractPlus

68. Writing Committee of the World Health Organization (WHO) consultation on human influenza A/H5. Avian influenza A (H5N1) infection in humans. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:1374-85. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16192482?dopt=AbstractPlus

69. Ungchusak K, Auewarakul P, Dowell SF et al. Probable person-to-person transmission of Avian influenza A (H5N1). N Engl J Med. 2005; 352:333-40. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15668219?dopt=AbstractPlus

70. Kiso M, Mitamura K, Sakai-Tagawa Y et al. Resistant influenza A viruses in children treated with oseltamivir: descriptive study. Lancet. 2004; 364:759-65. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15337401?dopt=AbstractPlus

73. Le QM, Kiso M, Someya K et al. Isolation of drug-resistant H5N1 virus. Nature. 2005; 437.

74. Machado CM, Boas LSV, Mendes AVA et al. Use of oseltamivir to control influenza complications after bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004; 34:111-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15094755?dopt=AbstractPlus

75. Chik KW, Li CK, Chan PKS et al. Oseltamivir prophylaxis during the influenza season in a paediatric cancer centre: prospective observational study. Hong Kong Med J. 2004; 10:103-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15075430?dopt=AbstractPlus

81. deJong MD, Tran TT, Truong HK et al. Oseltamivir resistance during treatment of influenza A (H5N1) infection. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:2667-72. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16371632?dopt=AbstractPlus

83. Edwards ET, Truffa MM. One-year post pediatric exclusivity postmarketing adverse events review. Drug: oseltamivir phosphate. 24 Aug 2005. From FDA website. Accessed 10 Jan 2006. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/07/briefing/2007-4325b2_17_Tamiflu%20Pediatric%20Review%202007.pdf

84. US Food and Drug Administration. Pediatric safety update for Tamiflu-Pediatric Advisory Committee meeting. 18 Nov 2005. From FDA website. Accessed 10 Jan 2006. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/05/briefing/2005-4180b_06_06_summary.pdf

85. Moscona A. Oseltamivir resistance-disabling our influenza defenses. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:2633-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16371626?dopt=AbstractPlus

88. US Food and Drug Administration. Tamiflu pediatric adverse events: questions and answers. From FDA website. Accessed 17 Mar 2006. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm107840.htm

92. Snell P, Oo C, Dorr A et al. Lack of pharmacokinetic interaction between the oral anti-influenza neuraminidase inhibitor prodrug oseltamivir and antacids. Clin Pharmacol. 2002; 54:372-7.

93. Ison MG, Gubareva LV, Atmar RL et al. Recovery of drug-resistant influenza virus from immunocompromised patients: a case series. J Infect Dis. 2006; 193:760-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16479508?dopt=AbstractPlus

94. World Health Organization. WHO rapid advice guidelines on pharmacological management of humans infected with avian influenza A (H5N1) virus. World Health Organization 2006. From WHO website. Accessed 2014 Feb 4. http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/WHO_PSM_PAR_2006.6.pdf

100. Grohskopf LA, Alyanak E, Ferdinands JM et al. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2021-22 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021; 70:1-28. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34448800?dopt=AbstractPlus

101. Nichols WG, Guthrie KA, Corey L, Boeckh M. Influenza infections after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: risk factors, mortality, and the effect of antiviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004; 39:1300-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15494906?dopt=AbstractPlus

104. World Health Organization. Avian influenza. From WHO website. Accessed 2019 Nov 14. http://www.who.int/topics/avian_influenza/en/

105. American Academy of Pediatrics. Red Book: 2018-2021 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 31st ed. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2018: 476-90.

112. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases. Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children, 2021-2022. Pediatrics. 2021; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34493538?dopt=AbstractPlus

114. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: Swine influenza A (H1N1) infections–California and Texas, April 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009; 58:435-7.

116. Uyeki TM, Bernstein HH, Bradley JS et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America: 2018 Update on Diagnosis, Treatment, Chemoprophylaxis, and Institutional Outbreak Management of Seasonal Influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 2019; 68:e1-e47. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30566567?dopt=AbstractPlus

118. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in a school–New York City, April 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009; 58 (Dispatch):1-3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19145219?dopt=AbstractPlus

119. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus infection–Mexico, March-April 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009; 58 (Dispatch):1-3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19145219?dopt=AbstractPlus

120. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza antiviral medications: summary for clinicians. From CDC website. Accessed 2021 Sep 3. http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm

121. Food and Drug Administration. Tamiflu letter for emergency use authorization. April 27, 2009. From FDA website. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm100228.htm

123. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update: influenza activity - United States, August 30, 2009-March 27, 2010, and composition of the 2010-11 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010; 59:423-30. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20395936?dopt=AbstractPlus

124. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: drug susceptibility of swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) viruses, April 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009; 58:433-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19407738?dopt=AbstractPlus

132. Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Eng J Med. 2009; 361.

134. Kroger A, Bahta L, Hunter P. General best practice guidelines for immunization. Best practices guidance of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). From CDC website. Accessed 2021 Feb 3. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/downloads/general-recs.pdf

135. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The 2009 H1N1 pandemic: summary highlights, April 2009–April 2010. From CDC website. Accessed 28 Oct 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/cdcresponse.htm

141. Barron H. Dear healthcare provider letter regarding Tamiflu (oseltamivir). Nutley, NJ: Roche; 2009 Sep 23.

142. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for obstetric health care providers related to use of antiviral medications in the treatment and prevention of influenza. From CDC website. Accessed 2021 Sep 3. http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/avrec_ob.htm

144. Fiore AE, Fry A, Shay D et al. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza --- recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011; 60:1-24. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21248682?dopt=AbstractPlus

147. . Summary of human infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus reported to WHO, January 2003-March 2009: cluster-associated cases. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2010; 85:13-20. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20095108?dopt=AbstractPlus

148. World Health Organization. Global alert and response (GAR). WHO recommendations for the post-pandemic period. From WHO website. Accessed Sep 29, 2010. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/notes/briefing_20100810/en/index.html

150. Food and Drug Administration. Tamiflu and relenza emergency use authorization disposition letters and question and answer attachments. June 22, 2010. From FDA website. Accessed 2010 Oct 1. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm216249.htm

151. Writing Committee of the WHO Consultation on Clinical Aspects of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza, Bautista E, Chotpitayasunondh T et al. Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362:1708-19. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20445182?dopt=AbstractPlus

152. Adisasmito W, Chan PK, Lee N et al. Effectiveness of antiviral treatment in human influenza A(H5N1) infections: analysis of a Global Patient Registry. J Infect Dis. 2010; 202:1154-60. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20831384?dopt=AbstractPlus

153. Ujike M, Shimabukuro K, Mochizuki K et al. Oseltamivir-resistant influenza viruses A (H1N1) during 2007-2009 influenza seasons, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010; 16:926-35. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3086245&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20507742?dopt=AbstractPlus

154. Inoue M, Barkham T, Leo YS et al. Emergence of Oseltamivir-Resistant Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Virus within 48 Hours. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010; 16:1633-6. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3294403&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20875299?dopt=AbstractPlus

155. Tramontana AR, George B, Hurt AC et al. Oseltamivir resistance in adult oncology and hematology patients infected with pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010; 16:1068-75. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3321901&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20587176?dopt=AbstractPlus

156. Hill-Cawthorne GA, Schelenz S, Lawes M et al. Oseltamivir-resistant pandemic (H1N1) 2009 in patient with impaired immune system. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010; 16:1185-6. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3321897&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20587208?dopt=AbstractPlus

157. van der Vries E, Stelma FF, Boucher CA. Emergence of a multidrug-resistant pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363:1381-2. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20879894?dopt=AbstractPlus

158. Cheng PK, To AP, Leung TW et al. Oseltamivir- and amantadine-resistant influenza virus A (H1N1). Emerg Infect Dis. 2010; 16:155-6. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2874384&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20031069?dopt=AbstractPlus

161. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Intravenous influenza antiviral medications and CDC considerations related to investigational use of intravenous zanamivir for 2013–2014 influenza season. From CDC website. Accessed 2014 Feb 3. http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/intravenous-antivirals.htm

162. Hayden FG, de Jong MD. Emerging influenza antiviral resistance threats. J Infect Dis. 2011; 203:6-10. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3086431&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21148489?dopt=AbstractPlus

163. . Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2011-2012 northern hemisphere influenza season. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2011; 86:81-91.

166. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 14th ed. Washington DC: Public Health Foundation; 2021 May. Updates may be available at CDC website. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/flu.html

167. . Review of the 2010-2011 winter influenza season, northern hemisphere. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2011; 86:221-32. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21661270?dopt=AbstractPlus

168. Govorkova EA, Baranovich T, Seiler P et al. Antiviral resistance among highly pathogenic influenza A (H5N1) viruses isolated worldwide in 2002-2012 shows need for continued monitoring. Antiviral Res. 2013; 98:297-304. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3648604&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23458714?dopt=AbstractPlus

169. Hu Y, Lu S, Song Z et al. Association between adverse clinical outcome in human disease caused by novel influenza A H7N9 virus and sustained viral shedding and emergence of antiviral resistance. Lancet. 2013; 381:2273-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23726392?dopt=AbstractPlus

170. Wu Y, Bi Y, Vavricka CJ et al. Characterization of two distinct neuraminidases from avian-origin human-infecting H7N9 influenza viruses. Cell Res. 2013; 23:1347-55. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3847574&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24165891?dopt=AbstractPlus

171. Chen H, Yuan H, Gao R et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of a fatal case of avian influenza A H10N8 virus infection: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2014; 383:714-21. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24507376?dopt=AbstractPlus

172. Okomo-Adhiambo M, Fry AM, Su S et al. Oseltamivir-Resistant Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 Viruses, United States, 2013-14. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015; 21:136-41. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4285251&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25532050?dopt=AbstractPlus

173. Mishin VP, Hayden FG, Gubareva LV. Susceptibilities of antiviral-resistant influenza viruses to novel neuraminidase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005; 49:4515-20. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1280118&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16251290?dopt=AbstractPlus

174. Takashita E, Ejima M, Itoh R et al. A community cluster of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus exhibiting cross-resistance to oseltamivir and peramivir in Japan, November to December 2013. Euro Surveill. 2014; 19:. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24434172?dopt=AbstractPlus

175. Gubareva LV, Webster RG, Hayden FG. Comparison of the activities of zanamivir, oseltamivir, and RWJ-270201 against clinical isolates of influenza virus and neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant variants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001; 45:3403-8. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=90844&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11709315?dopt=AbstractPlus

176. BioCryst Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Rapivab (peramivir) injection for intravenous use prescribing information. Durham, NC: 2014 Dec.

177. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health Alert Network. Bird infections with highly-pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N2), (H5N8), and (H5N1) viruses: recommendations for human health investigations and responses. CDCHAN-00378. June 2, 2015. From CDC website. http://emergency.cdc.gov/han/han00378.asp

178. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidance on the use of antiviral medications for treatment of human infections with novel influenza A viruses associated with severe human disease. From CDC website. Accessed 2021 Sep 3. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/novel-av-treatment-guidance.htm

179. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidance on influenza antiviral chemoprophylaxis of persons exposed to birds with avian influenza A viruses associated with severe human disease or with the potential to cause severe human disease. From CDC website. Accessed 2021 Sep 3. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/guidance-exposed-persons.htm

180. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidance on follow-up of close contacts of persons infected with novel influenza A viruses associated with severe human disease and on the use of antiviral medications for chemoprophylaxis. From CDC website. Accessed 2021 Sep 3. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/novel-av-chemoprophylaxis-guidance.htm

181. World Health Organization. Cumulative number of confirmed human cases of avian influenza A(H5N1) reported to WHO, 2003-2021. From WHO website. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/influenza/h5n1-human-case-cumulative-table/2021_may_tableh5n1.pdf?sfvrsn=79ac908a

182. Tan KX, Jacob SA, Chan KG et al. An overview of the characteristics of the novel avian influenza A H7N9 virus in humans. Front Microbiol. 2015; 6:140. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4350415&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25798131?dopt=AbstractPlus

183. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Emergence of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus causing severe human illness - China, February-April 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013; 62:366-71. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4605021&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23657113?dopt=AbstractPlus

184. Jhung MA, Nelson DI, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Outbreaks of avian influenza A (H5N2), (H5N8), and (H5N1) among birds--United States, December 2014-January 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 64:111. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4584850&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25654614?dopt=AbstractPlus

185. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health Alert Network. CDC health update regarding treatment of patients with influenza with antiviral medications. CDCHAN-0375. January 9, 2015. From CDC website. http://emergency.cdc.gov/HAN/han00375.asp

186. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Influenza activity--United States, 2012-13 season and composition of the 2013-14 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013; 62:473-9. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4604847&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23760189?dopt=AbstractPlus

187. Gao HN, Lu HZ, Cao B et al. Clinical findings in 111 cases of influenza A (H7N9) virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368:2277-85. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23697469?dopt=AbstractPlus

188. Epperson S, Blanton L, Kniss K et al. Influenza activity - United States, 2013-14 season and composition of the 2014-15 influenza vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014; 63:483-90. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24898165?dopt=AbstractPlus

189. . Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2014-2015 northern hemisphere influenza season. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2014; 89:93-104. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24707514?dopt=AbstractPlus

190. World Health Organization. Human infection with avian influenza A (H5) viruses. 2021 Aug 13. From WHO website. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/wpro---documents/emergency/surveillance/avian-influenza/ai-20210813.pdf?sfvrsn=30d65594_157

191. World Health Organization. Human infection with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus – China. From WHO website. https://www.who.int/csr/don/26-october-2017-ah7n9-china/en/

192. Davlin SL, Blanton L, Kniss K et al. Influenza Activity - United States, 2015-16 Season and Composition of the 2016-17 Influenza Vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016; 65:567-75. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27281364?dopt=AbstractPlus

193. . Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2016–2017 northern hemisphere influenza season. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2016; 91:121-32. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26971356?dopt=AbstractPlus

194. Blanton L, Alabi N, Mustaquim D et al. Update: Influenza Activity in the United States During the 2016-17 Season and Composition of the 2017-18 Influenza Vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017; 66:668-676. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5687497&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28662019?dopt=AbstractPlus

195. . Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2017–2018 northern hemisphere influenza season. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2017; 92:117-28. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28303704?dopt=AbstractPlus