Metoclopramide (Monograph)

Brand names: Gimoti, Reglan

Drug class: Prokinetic Agents

- Antiemetic Agents

- Benzamides

VA class: AU300

Molecular formula: C14H22ClN3O22O

CAS number: 54143-57-6

Warning

- Tardive Dyskinesia

-

May result in tardive dyskinesia.5 267 Risk increases with increasing duration of therapy and total cumulative dose.5 267 (See Tardive Dyskinesia under Cautions.)

-

Discontinue metoclopramide in patients who develop signs or symptoms of tardive dyskinesia.5 267 Symptoms may lessen or resolve in some patients after discontinuance.5 267

-

Avoid treatment durations >12 weeks because of increased risk of developing tardive dyskinesia with longer-term use.5

Introduction

Antiemetic; stimulant of upper GI motility (prokinetic agent);1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 263 267 potent dopamine-receptor antagonist.2 4 5 7 19 28 34 52 267

Uses for Metoclopramide

Diabetic Gastric Stasis

Symptomatic treatment of acute and recurrent diabetic gastric stasis (gastroparesis).5 7 32 44 76 77 78 79 80 83 84 88 89 267 277 286 287

Symptomatic treatment may include dietary modifications, optimization of glycemic control, avoidance of drugs that adversely affect GI motility, antiemetics for relief of associated nausea and vomiting, and, in more severe cases, prokinetic agents to improve gastric emptying.279 288 289 291 The American Diabetes Association states that metoclopramide should be reserved for use in patients with severe diabetic gastric stasis that is unresponsive to other therapies, since evidence of benefit is weak and the drug is associated with serious adverse effects.279

Postsurgical Gastric Stasis

Has been used for the symptomatic treatment of acute and chronic postsurgical gastric stasis† [off-label] following vagotomy and gastric resection or vagotomy and pyloroplasty.31 37 44 49 84 113 114 115 148 149 150

Prevention of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting

Prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting when nasogastric suction is considered undesirable.4 125 267

Prevention of Cancer Chemotherapy-induced Emesis

Used parenterally in high doses for the prevention of nausea and vomiting associated with emetogenic cancer chemotherapy including cisplatin alone or in combination with other antineoplastic agents.97 98 99 100 101 102 103 263 267

Prevention of nausea and vomiting associated with other antineoplastic agents (e.g., cyclophosphamide, dacarbazine, doxorubicin, methotrexate) and with cancer chemotherapy regimens that do not include cisplatin.103 144 145 146 147 218 263 267

ASCO does not consider metoclopramide an appropriate first-line antiemetic for any group of patients receiving chemotherapy of high emetic risk and states that this drug should be reserved for patients unable to tolerate or refractory to first-line agents (i.e., a type 3 serotonin [5-HT3] receptor antagonist [e.g., dolasetron, granisetron, ondansetron, palonosetron] with dexamethasone and aprepitant).263

ASCO states that the combination of a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, dexamethasone, and aprepitant is preferred in patients receiving combination chemotherapy with an anthracycline and cyclophosphamide; ASCO recommends combined therapy with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone for other chemotherapy regimens of moderate emetic risk (i.e., 31–90% incidence of emesis without antiemetics) and dexamethasone alone for chemotherapy regimens of low emetic risk (i.e., 11–30% incidence).263

In patients experiencing nausea and vomiting despite recommended prophylaxis regimens, ASCO recommends that clinicians consider adding a benzodiazepine (e.g., alprazolam, lorazepam), butyrophenone, or phenothiazine to the regimen or substituting high-dose IV metoclopramide for the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist in the regimen.263

Antiemetics can be prescribed on an as-needed basis for chemotherapy regimens with minimal emetic risk (<10% incidence of emesis without antiemetics).263

Metoclopramide has been used orally† [off-label] for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. 177 218 221 224 263 264 265 266

Oral† [off-label] metoclopramide has been effective when given in combination with dexamethasone for the prevention of delayed emesis in patients receiving chemotherapy.263 264 265 266 For prevention of delayed emesis in patients receiving cisplatin or other chemotherapy of high emetic risk, ASCO recommends the combination of dexamethasone and aprepitant.263

Intubation of the Small Intestine

Used parenterally to facilitate small intestine intubation when the tube (e.g., endoscope, biopsy tube) does not pass through the pylorus during 10 minutes of conventional maneuvers.105 106 107 109 176 267

Radiographic Examination of the Upper GI Tract

Used parenterally to stimulate gastric emptying and intestinal transit of barium when delayed emptying interferes with radiographic examination of the stomach and/or small intestine.4 43 110 184 267

Gastroesophageal Reflux

Short-term (4–12 weeks) relief of symptomatic, documented gastroesophageal reflux in adults who are unresponsive to conventional therapy (e.g., changes in lifestyle, habits, or diet; weight reduction; acid-suppressive therapy).5 9 30 39 40 41 42 111 112 116 117 125 129 185 186 187 188 189 190 258

Regular use for this purpose has declined; proton-pump inhibitors provide greater control of acid reflux and heartburn.258 273 274 Some experts recommend against use of metoclopramide for this purpose based on the drug’s adverse effect profile and lack of high-quality supporting data.273 274

Migraine

Has been used for the management of migraine† [off-label].4 125 283 284 285 Some experts state that metoclopramide may be considered as adjunctive therapy for control of nausea in patients with acute migraine attacks and that the IV drug may be considered for relief of migraine pain.283 284 285

Related/similar drugs

ibuprofen, omeprazole, ondansetron, famotidine, hydroxyzine, pantoprazole, amitriptyline

Metoclopramide Dosage and Administration

Administration

Administer orally, intranasally, by direct IV injection or IV infusion, or IM.5 263 267 277

Metoclopramide therapy, including all dosage forms and routes of administration, should not exceed 12 weeks’ duration because of risk of tardive dyskinesia with longer-term use.5 267 268 269 277 (See Tardive Dyskinesia under Cautions.)

Oral Administration

Oral formulations of metoclopramide are recommended for use in adults only.5 268 269 278 (See Pediatric Use under Cautions.)

Administer orally on an empty stomach as conventional tablets, oral solution, or orally disintegrating tablets.5 268 269 278 At least one manufacturer states that dose should not be repeated if inadvertently administered with food.278 (See Food under Pharmacokinetics.)

Orally Disintegrating Tablets

Remove tablet from the blister packaging with dry hands and immediately place it on the tongue.278 Tablet should disintegrate in approximately one minute (range: 10 seconds to 14 minutes).278 Discard any tablet that breaks or crumbles during handling.278

Intended to be taken without liquid; not known whether administration with liquid affects pharmacokinetics.278

Intranasal Administration

Metoclopramide nasal spray is recommended for use in adults only.277 (See Pediatric Use under Cautions.)

Administer by nasal inhalation using a metered-dose spray pump.277 For information on administration technique, consult manufacturer's instructions for use.277

Prime the pump prior to first use or if not used for ≥2 weeks.277

IV Administration

For solution and drug compatibility information, see Compatibility under Stability.

Dilution

For direct IV injection, use without further dilution.267

If dose is >10 mg, dilute in 50 mL of a compatible IV solution.267

For IV infusion, manufacturer recommends dilution in 50 mL of 5% dextrose, 0.9% sodium chloride, 5% dextrose and 0.45% sodium chloride, Ringer’s, or lactated Ringer’s injection.267

Manufacturer states that 0.9% sodium chloride injection is preferred because metoclopramide hydrochloride is most stable in this solution.267

Rate of Administration

Direct IV injection: Administer each 10 mg slowly over 1–2 minutes.267 Rapid IV injection may cause transient but intense feelings of anxiety and restlessness, followed by drowsiness.267

IV infusion: Administer slowly over ≥15 minutes.267

IM Administration

Inject without further dilution.267

Dosage

Available as metoclopramide hydrochloride; dosage expressed in terms of metoclopramide.5 267

Nasal spray delivers 15 mg of metoclopramide per 70-µL metered spray.277 Each bottle contains 9.8 mL of solution, which is sufficient for administration 4 times daily over a period of 4 weeks.277

Dosage adjustment required in patients receiving concomitant therapy with potent CYP2D6 inhibitors.5 (See Drugs Affecting Hepatic Microsomal Enzymes under Interactions.)

Pediatric Patients

Intubation of the Small Intestine

IV

Children <6 years of age: Usually, one 0.1-mg/kg dose given by direct IV injection.267

Children 6–14 years of age: Usually, one 2.5- to 5-mg dose given by direct IV injection.267

Children >14 years of age: Usually, one 10-mg dose given by direct IV injection.267

Adults

Diabetic Gastric Stasis

Use lowest effective dosage to reduce risk of adverse effects.288 289

Oral

10 mg 4 times daily, given 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime.5 Continue for 2–8 weeks, depending on response.5

Intranasal

15 mg (one spray in one nostril) administered 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime.277 Continue for 2–8 weeks, depending on response.277

IV, then Oral

If symptoms are severe or oral use is not feasible, 10 mg 4 times daily, given by direct IV injection 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime.5 267 278 Continued use for up to 10 days may be required until symptoms subside enough to allow oral administration;5 267 278 however, thoroughly assess the risks and benefits prior to continuing therapy.267

IM, then Oral

If symptoms are severe or oral use is not feasible, 10 mg 4 times daily, given by IM injection 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime.5 267 278 Continued use for up to 10 days may be required until symptoms subside enough to allow oral administration;5 267 278 however, thoroughly assess the risks and benefits prior to continuing therapy.267

Prevention of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting

IM

Manufacturer states that usual dose is 10 mg administered near the end of the surgical procedure; 20 mg also may be used.267

Prevention of Cancer Chemotherapy-induced Emesis

Oral† [off-label]

When given in combination with dexamethasone in clinical trials for the prevention of delayed emesis (i.e., vomiting occurring ≥24 hours after chemotherapy), 20–40 mg (or 0.5 mg/kg) of metoclopramide has been given 2–4 times daily for 3 or 4 days.263 264 265 266

IV

Manufacturer states that metoclopramide usually is given by IV infusion 30 minutes before administration of chemotherapy, and then repeated every 2 hours for 2 additional doses followed by every 3 hours for 3 additional doses.267 Manufacturer states that initial 2 doses should be 2 mg/kg if highly emetogenic chemotherapy used;267 for less emetogenic drugs or regimens, initial 1-mg/kg dose may be sufficient.267 However, combinations of other antiemetic agents generally are preferred as first-line regimens in patients receiving chemotherapy of moderate or high emetic risk (see Prevention of Cancer Chemotherapy-induced Emesis under Uses). 263

Intubation of the Small Intestine

IV

Usually, one 10-mg dose given by direct IV injection.267

Radiographic Examination of the Upper GI Tract

IV

Usually, one 10-mg dose given by direct IV injection.267

Gastroesophageal Reflux

Oral

If continuous dosing is required, 10–15 mg 4 times daily, given 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime for 4–12 weeks; base treatment duration on endoscopic evaluation of response.5

For intermittent symptoms or symptoms at specific times of the day, one 20-mg dose before the provocative situation may be preferred to daily administration of multiple doses.5

Prescribing Limits

Adults

Maximum 12 week's duration, including all dosage forms and routes of administration.5 277 (See Boxed Warning and see Tardive Dyskinesia under Cautions.)

Diabetic Gastric Stasis

Oral

Maximum 40 mg daily.5

Intranasal

Maximum 4 times daily (i.e., maximum 60 mg daily).277

Gastroesophageal Reflux

Oral

Maximum 60 mg daily.5

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

Diabetic Gastric Stasis

Oral

Moderate or severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class B or C): 5 mg 4 times daily, given 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime (maximum 20 mg daily).5

Mild hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class A): Patient may receive usual recommended dosage.5

Intranasal

Moderate or severe hepatic impairment: Not recommended because dosage cannot be adjusted.277

Mild hepatic impairment: Patient may receive usual recommended dosage.277

Gastroesophageal Reflux

Oral

Moderate or severe hepatic impairment: 5 mg 4 times daily, given 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime, or 10 mg 3 times daily (maximum 30 mg daily).5

Mild hepatic impairment: Patient may receive usual recommended dosage.5

Renal Impairment

Modify dosage according to degree of renal impairment.5 54 58 59 135 142 267

In patients with Clcr <40 mL/minute, manufacturers recommend an initial parenteral dosage of approximately 50% of the usual dosage.267 Subsequently, increase or decrease dosage according to response and tolerance.267

Diabetic Gastric Stasis

Oral

Moderate or severe renal impairment (Clcr <60 mL/minute): 5 mg 4 times daily, given 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime (maximum 20 mg daily).5

End-stage renal disease, including hemodialysis or continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD): 5 mg twice daily (maximum 10 mg daily).5

Intranasal

Moderate or severe renal impairment (Clcr <60 mL/minute): Not recommended because dosage cannot be adjusted.277

Mild renal impairment (Clcr ≥60 mL/minute): Patient may receive usual recommended dosage.277

Gastroesophageal Reflux

Oral

Moderate or severe renal impairment (Clcr ≤60 mL/minute): 5 mg 4 times daily, given 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime, or 10 mg 3 times daily (maximum 30 mg daily).5

End-stage renal disease, including hemodialysis or CAPD: 5 mg 4 times daily, given 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime, or 10 mg twice daily (maximum 20 mg daily).5

Geriatric Patients

Reduce initial dosage.5 (See Geriatric Use under Cautions.)

Administer lowest effective dosage.267

Diabetic Gastric Stasis

Oral: Initially, 5 mg 4 times daily, given 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime.5 May titrate to 10 mg 4 times daily based on response and tolerability (maximum 40 mg daily).5

Intranasal: Metoclopramide nasal spray not recommended as initial therapy in patients ≥65 years of age.277 May switch from an alternative metoclopramide preparation given at a stable dosage of 10 mg 4 times daily to the nasal formulation given at a dosage of 15 mg (one spray in one nostril) given 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime (maximum 4 times daily).277

Gastroesophageal Reflux

Oral: Initially, 5 mg 4 times daily, given 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime.5 May titrate to 10–15 mg 4 times daily based on response and tolerability (maximum 60 mg daily).5

Poor CYP2D6 Metabolizers

IV or IM: Manufacturers make no specific dosage recommendations.267

Diabetic Gastric Stasis

Oral: 5 mg 4 times daily, given 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime (maximum 20 mg daily).5

Intranasal: Metoclopramide nasal spray not recommended because dosage cannot be adjusted.277

Gastroesophageal Reflux

Oral: 5 mg 4 times daily, given 30 minutes before meals and at bedtime, or 10 mg 3 times daily (maximum 30 mg daily).5

Cautions for Metoclopramide

Contraindications

-

History of tardive dyskinesia or dystonic reaction to metoclopramide.5

-

Mechanical obstruction or perforation or other situations in which stimulation of GI motility might be dangerous.5 267

-

GI hemorrhage5 267 (however, has been used to empty the stomach of blood prior to endoscopy in patients with acute upper GI hemorrhage).4 125

-

Pheochromocytoma or other catecholamine-releasing paragangliomas (due to potential for hypertensive/pheochromocytoma crisis).5 267

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Tardive Dyskinesia

May cause tardive dyskinesia, a potentially irreversible disorder manifested by involuntary movements of the tongue, face, mouth, or jaw, and sometimes by involuntary movements of the trunk and/or extremities; movements may be choreoathetotic in appearance.5 93 94 130 157 158 159 267 270 271 272 (See Boxed Warning.)

Risk of developing tardive dyskinesia is increased in geriatric patients, especially older women, and patients with diabetes mellitus.5 267 270 271 272

Risk of developing tardive dyskinesia and likelihood that it will become irreversible increase with duration of therapy and total cumulative dose; tardive dyskinesia occurs in about 20% of patients receiving the drug for >12 weeks.5 267 270 271 272

Avoid treatment durations >12 weeks, including all dosage forms and routes of administration, and reduce dosage in geriatric patients.5 267 272

Avoid use in patients receiving other drugs that are likely to cause tardive dyskinesia (e.g., antipsychotic agents).5

Discontinue metoclopramide immediately in patients who develop signs or symptoms of tardive dyskinesia.5 267 270 271 Tardive dyskinesia may remit, either partially or completely, in some patients within several weeks to months after discontinuance.5 267 271

Metoclopramide may suppress or partially suppress signs of tardive dyskinesia, thereby masking the underlying disease process; effect of this suppression on the long-term course of tardive dyskinesia is unknown.5 267 Do not use metoclopramide for symptomatic control of tardive dyskinesia.5 267

Vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors (e.g., deutetrabenazine, valbenazine) shown to be effective in reducing symptoms of tardive dyskinesia in controlled clinical studies.417 418 419 420 421 422 423 424

Sensitivity Reactions

Tartrazine Sensitivity

Some formulations of metoclopramide oral solution may contain tartrazine (FD&C yellow No. 5), which may cause allergic reactions including bronchial asthma in susceptible individuals.268 Incidence of tartrazine sensitivity is low, but it frequently occurs in patients who are sensitive to aspirin.268

Procainamide Cross-sensitivity

Theoretical potential for patients who are allergic to procainamide to exhibit cross-sensitivity to metoclopramide (since the drugs are structurally similar).11 12

Other Warnings and Precautions

Extrapyramidal Symptoms

Potential for extrapyramidal reactions,4 5 90 91 125 169 205 206 207 267 especially in pediatric patients and adults <30 years of age or when high doses (e.g., IV doses for prophylaxis of cancer chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting) are administered.5 91 169 267

Avoid use in patients receiving other drugs that are likely to cause extrapyramidal reactions (e.g., antipsychotic agents).5

Commonly manifested as acute dystonic reactions or akathisia; stridor and dyspnea (possibly due to laryngospasm) reported rarely.5 267

Generally occur within 24–48 hours after starting therapy5 205 206 207 267 and usually subside within 24 hours following drug discontinuance.4 90 205

Most patients respond rapidly to treatment with diazepam4 or an agent with central anticholinergic activity (e.g., diphenhydramine hydrochloride 20–50 mg orally, IM, or IV;5 267 276 benztropine 1–2 mg IM5 267 ).4 5 170 206 207 267

Akathisia appears to be related to peak drug concentration.135 137 If akathisia resolves, may consider reinitiating metoclopramide at a lower dosage.5

Parkinsonian Symptoms

Parkinsonian symptoms (e.g., tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, akinesia, mask-like facies) have occurred.9 54 62 160

Possible exacerbation of parkinsonian symptoms;5 9 54 62 160 267 avoid use in patients with parkinsonian syndrome and in other patients receiving antiparkinsonian drugs.5 267

More common during first 6 months of therapy but occur occasionally after longer periods.5 267

Symptoms generally subside within 2–3 months following drug discontinuance.5 267

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS)

NMS, a potentially fatal symptom complex characterized by hyperpyrexia, muscular rigidity, altered mental status, and autonomic dysfunction, reported with dopamine antagonists.5 208 267

Has occurred following metoclopramide overdosage in patients receiving concomitant therapy with other drugs associated with NMS.5

Avoid use in patients receiving other drugs associated with NMS (e.g., typical or atypical antipsychotic agents).5

Important to determine whether untreated or inadequately treated extrapyramidal reactions and serious medical illness (e.g., pneumonia, systemic infection) may coexist.5 267 Also consider the possibility of central anticholinergic toxicity, heat stroke, malignant hyperthermia, drug fever, serotonin syndrome, and primary CNS pathology.5 267

Immediately discontinue metoclopramide and other drugs not considered essential, provide intensive symptomatic treatment, monitor patient, and treat any concomitant serious medical condition for which specific therapies are available.5 267

Depression

Mild to severe depression (including suicidal ideation and suicide) has occurred in patients with or without history of depression.5 210 211 215 267

Avoid use in patients with a history of mental depression.5

Hypertension

May increase BP; increase in circulating catecholamines reported in hypertensive patients.5 Avoid use in patients with hypertension and in those receiving MAO inhibitors.5

Hypertensive crisis reported in patients with undiagnosed pheochromocytoma; discontinue metoclopramide in any patient who has a rapid increase in BP.5 (See Contraindications under Cautions.)

Fluid and Electrolyte Effects

Possible transient increases in plasma aldosterone concentrations and sodium retention; closely monitor patients (e.g., those with hepatic impairment, CHF, or cirrhosis) at risk of developing fluid retention and volume overload or hypokalemia.3 5 69 267

Discontinue metoclopramide if fluid retention or volume overload occurs at any time during therapy.5 267

Hyperprolactinemia

Stimulates prolactin secretion.65 66 67 68 83 Hyperprolactinemia may result in impaired gonadal steroidogenesis and inhibition of reproductive function in both females and males.5 Galactorrhea,4 5 8 67 82 267 gynecomastia,5 112 267 menstrual disorders (e.g., amenorrhea),5 82 164 166 267 and impotence5 267 reported.

Hyperprolactinemia may potentially stimulate prolactin-dependent breast cancer.5 However, some clinical and epidemiologic studies have not shown an association between dopamine D2-receptor antagonists and tumorigenesis in humans.5

CNS Depression

Drowsiness may occur, particularly at higher dosages.5 267

Performance of activities requiring mental alertness and physical coordination (operating machinery, driving a motor vehicle) may be impaired.5 267 Concomitant use of CNS depressants and drugs that cause extrapyramidal reactions may increase mental and/or physical impairment; avoid such concomitant use.5 267

Pharmacogenomics

Metoclopramide elimination may be slower in poor CYP2D6 metabolizers than in intermediate, extensive, or ultra-rapid CYP2D6 metabolizers; poor metabolizers may be at increased risk of dystonic and other adverse reactions.5 Reduced dosage recommended.5 (See Poor CYP2D6 Metabolizers under Dosage and Administration.)

Patients with Cytochrome-b5 Reductase Deficiency

Patients with cytochrome-b5 reductase deficiency have an increased risk of methemoglobinemia and/or sulfhemoglobinemia when metoclopramide is administered.5 267

Patients with Glucose-6-phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency

Methylene blue is not recommended for treatment of metoclopramide-induced methemoglobinemia in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G-6-PD) deficiency.5 267

Phenylketonuria

Each 5- or 10-mg orally disintegrating tablet of metoclopramide contains aspartame, which is metabolized in the GI tract to provide 4.7 mg of phenylalanine per tablet.278

GI Anastomosis or Closure

When deciding whether to use metoclopramide or NG suction to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting, consider the possibility that metoclopramide theoretically could produce increased pressure on suture lines following GI anastomosis or closure.267

Withdrawal Effects

Adverse reactions, particularly CNS reactions, may occur following discontinuance of drug.5 Some patients may experience withdrawal symptoms including dizziness, nervousness, and/or headaches following discontinuance.5

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Published studies, including retrospective cohort studies, national registry studies, and meta-analyses, have not revealed an increased risk of adverse pregnancy-related outcomes with metoclopramide use during pregnancy.5

No adverse developmental effects observed in animal studies.5

Crosses the placenta and may cause extrapyramidal reactions and methemoglobinemia in neonates whose mothers received the drug during delivery; monitor for extrapyramidal effects.5 (See Extrapyramidal Symptoms under Cautions.)

Lactation

Distributed into milk.5 139 140 267 Estimated dose received by breast-fed infants is <10% of the maternal weight-adjusted dose.5 In one study, estimated dose from breast milk was 6–24 mcg/kg daily at 3–9 days postpartum and 1–13 mcg/kg daily at 8–12 weeks postpartum.5 Exposure expected to be similar following maternal doses of 10 mg administered orally or 15 mg administered intranasally.277

Adverse GI effects (e.g., intestinal discomfort, increased intestinal gas formation) reported in breast-fed infants exposed to metoclopramide.5

Although metoclopramide increases prolactin concentrations, data are inadequate to support drug-related effects on milk production.5

Consider developmental and health benefits of breast-feeding along with the mother's clinical need for metoclopramide and any potential adverse effects on the breast-fed child from the drug or underlying maternal condition.5

Monitor nursing neonates for extrapyramidal effects (dystonias) and methemoglobinemia.5 (See Pediatric Use under Cautions.)

Pediatric Use

Safety profile in adults cannot be extrapolated to pediatric patients.267 Dystonias and other extrapyramidal reactions are more common in pediatric patients than in adults.5 267

Safety and efficacy of oral and intranasal metoclopramide not established in pediatric patients; these formulations are not recommended for use in pediatric patients because of risk of tardive dyskinesia and other extrapyramidal reactions, as well as risk of methemoglobinemia in neonates.5 277

Safety and efficacy of metoclopramide injection in pediatric patients is established only for use to facilitate intubation of the small intestine.267 Use metoclopramide injection with caution; incidence of extrapyramidal reactions is increased in children.91 125 156 267

Use metoclopramide injection with caution in neonates.267 Neonatal susceptibility to methemoglobinemia is increased due to prolonged clearance (may cause excessive serum concentrations) in combination with decreased neonatal levels of cytochrome-b5 reductase.5 267

Geriatric Use

Geriatric patients are more likely to have decreased renal function and may be more sensitive to therapeutic or adverse effects of metoclopramide.5

Geriatric patients, especially older women, are at increased risk for tardive dyskinesia.5 267

Risk of adverse parkinsonian effects increases with increasing dosage;5 267 administer lowest effective dosage in geriatric patients.267 If parkinsonian symptoms develop, generally should discontinue metoclopramide before initiating specific antiparkinsonian therapy.267

Confusion and oversedation may occur.267

Substantially eliminated by the kidneys; risk of adverse reactions, including tardive dyskinesia, may be greater in patients with impaired renal function.5 267 (See Renal Impairment under Cautions.)

Consider reduced dosage.5 Select dosage with caution, usually initiating therapy at the low end of the dosage range, because of age-related decreases in renal function and concomitant disease and drug therapy.267 (See Geriatric Patients under Dosage and Administration).

Hepatic Impairment

Clearance may be reduced, resulting in increased exposure.5 (See Elimination: Special Populations, under Pharmacokinetics.) Possible increased risk of adverse effects.5 Reduced dosage recommended, depending on degree of hepatic impairment.5 (See Hepatic Impairment under Dosage and Administration.)

Possible increased risk of fluid retention and hypokalemia in patients with cirrhosis.3 5 69 267 (See Fluid and Electrolyte Effects under Cautions.) Discontinue if fluid retention or volume overload occurs at any time during therapy.5 267

Renal Impairment

Clearance may be reduced, resulting in increased exposure.5 54 59 142 192 267 (See Absorption: Special Populations, under Pharmacokinetics.) Possible increased risk of adverse effects, including tardive dyskinesia.5 267 Use with caution; reduced dosage recommended, depending on degree of renal impairment.5 54 58 59 69 135 142 267 (See Renal Impairment under Dosage and Administration.)

Common Adverse Effects

Restlessness, drowsiness, fatigue, lassitude, nausea, bowel disturbances (principally diarrhea).4 5 90 125 267

Adverse effects with orally disintegrating tablets and nasal spray are similar to those observed with conventional tablets, but dysgeusia is the most common adverse effect with the nasal spray.277 278

Drug Interactions

Metabolized by CYP2D6; also conjugated with glucuronic acid and sulfuric acid.5

Orally Administered Drugs

Possible decreased absorption of certain drugs that disintegrate, dissolve, and/or are absorbed mainly in the stomach.4 5 119 125 267

Possible enhanced rate and extent of absorption of drugs mainly absorbed in the small intestine.4 5 120 125 267

Drugs that Impair GI Motility

Possible reduced oral absorption of metoclopramide; monitor for reduced metoclopramide efficacy.5

Drugs Affecting Hepatic Microsomal Enzymes

Potent CYP2D6 inhibitors: Possible increased systemic exposure to metoclopramide and exacerbation of extrapyramidal symptoms.5 Reduce metoclopramide dosage (see Table 1).5 Examples of potent CYP2D6 inhibitors include, but are not limited to, bupropion, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and quinidine.5 227

|

Metoclopramide Route of Administration |

Adult Dosage Recommendation |

|---|---|

|

Oral |

Diabetic gastric stasis: 5 mg given 4 times daily (maximum 20 mg daily)5 Gastroesophageal reflux: 5 mg given 4 times daily or 10 mg given 3 times daily (maximum 30 mg daily)5 |

|

Parenteral |

Manufacturers make no specific recommendations267 |

|

Intranasal |

Not recommended; dosage cannot be adjusted to reduce exposure277 |

Drugs Metabolized by Hepatic Microsomal Enzymes

CYP2D6 substrates: In vitro studies suggest metoclopramide can inhibit CYP2D6, but interactions considered unlikely in vivo at clinically relevant concentrations.5

Drugs with Similar Adverse Effect Profiles

Drugs that are likely to cause extrapyramidal reactions: Possible additive effects; avoid concomitant use.4 5 267

Drugs known to cause tardive dyskinesia or NMS: Possible additive effects; avoid concomitant use.5 267

Dopaminergic Agents

Possible reduced efficacy of metoclopramide and possible exacerbation of parkinsonian symptoms due to opposing effects on dopamine.5 Avoid concomitant use; if concomitant use is required, monitor therapeutic effects.5

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Acetaminophen |

Possible enhanced rate and extent of acetaminophen absorption4 5 120 125 267 |

|

|

Anesthetic agents |

Acute hypotension reported with concomitant IV metoclopramide and hypotensive anesthetic agents (with or without ganglionic blocking agents) during neurosurgical procedures162 163 |

|

|

Anticholinergic agents (e.g., atropine) |

Antagonism of GI motility effects of metoclopramide 5 267 Impairment of GI motility by anticholinergic agent may reduce oral absorption of metoclopramide5 |

Monitor for reduced metoclopramide efficacy5 |

|

Antidiarrheal agents, antiperistaltic |

Impairment of GI motility by antiperistaltic agent may reduce oral absorption of metoclopramide5 |

Monitor for reduced metoclopramide efficacy5 |

|

Antipsychotic agents (e.g., butyrophenones, phenothiazines) |

Possible additive adverse effects, including increased frequency and severity of tardive dyskinesia, parkinsonian or other extrapyramidal symptoms, and NMS5 |

Avoid concomitant use5 |

|

Aspirin |

Possible enhanced rate and extent of aspirin absorption4 120 125 |

|

|

Atovaquone |

Possible decreased atovaquone absorption5 |

Monitor for reduced atovaquone efficacy5 |

|

CNS depressants (alcohol, opiates or other analgesics, sedatives or hypnotics, anxiolytic agents, anesthetics) |

Increased CNS depressant effects;5 267 possible enhanced rate and extent of alcohol absorption4 5 125 267 |

Avoid concomitant use5 |

|

Cyclosporine |

Possible enhanced rate and extent of cyclosporine absorption4 5 120 125 267 |

Monitor cyclosporine concentrations and adjust cyclosporine dosage as needed5 |

|

Diazepam |

Possible enhanced rate and extent of diazepam absorption4 120 125 |

|

|

Digoxin |

Monitor digoxin concentrations and adjust digoxin dosage as needed5 |

|

|

Dopamine agonists (e.g., apomorphine, bromocriptine, cabergoline, pramipexole, ropinirole, rotigotine) |

Possible reduced efficacy of metoclopramide and possible exacerbation of parkinsonian symptoms due to opposing effects on dopamine5 |

Avoid concomitant use; if concomitant use required, monitor therapeutic effects5 |

|

Fluoxetine |

Increased peak concentration and AUC of metoclopramide by 40 and 90%, respectively; possible exacerbation of extrapyramidal symptoms5 277 |

Reduce metoclopramide dosage5 (see Table 1) |

|

Fosfomycin |

Possible decreased fosfomycin absorption5 |

Monitor for reduced fosfomycin efficacy5 |

|

Insulin |

Possible alteration of glycemic control secondary to metoclopramide-related changes in the delivery of food to and the rate of absorption in the intestine5 267 |

Monitor blood glucose; adjustment of insulin dose or timing may be necessary5 267 |

|

Levodopa |

Possible enhanced rate and extent of levodopa absorption4 5 120 125 267 Possible reduced efficacy of metoclopramide and possible exacerbation of parkinsonian symptoms due to opposing effects on dopamine5 |

Avoid concomitant use; if concomitant use required, monitor therapeutic effects5 |

|

Lithium |

Possible enhanced rate and extent of lithium absorption4 120 125 |

|

|

MAO inhibitors |

Possible hypertensive reaction due to metoclopramide-induced release of catecholamines5 267 |

Avoid concomitant use5 |

|

Neuromuscular blocking agents |

Enhanced neuromuscular blockade due to metoclopramide inhibition of plasma cholinesterase5 |

Monitor for prolonged neuromuscular blockade5 |

|

Opiate analgesics |

Antagonism of GI motility effects of metoclopramide5 15 33 267 Impairment of GI motility by opiate may reduce oral absorption of metoclopramide5 |

Monitor for reduced metoclopramide efficacy5 |

|

Posaconazole |

Posaconazole oral suspension: Possible decreased posaconazole absorption5 Posaconazole delayed-release tablets: Absorption not affected5 |

Posaconazole oral suspension: Monitor for reduced posaconazole efficacy5 |

|

Sirolimus |

Possible enhanced sirolimus absorption5 |

Monitor sirolimus concentrations and adjust sirolimus dosage as needed5 |

|

Tacrolimus |

Possible enhanced tacrolimus absorption5 |

Monitor tacrolimus concentrations and adjust tacrolimus dosage as needed5 |

|

Tetracycline |

Possible enhanced rate and extent of tetracycline absorption4 5 120 125 267 |

Metoclopramide Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Following oral administration, rapidly and almost completely absorbed;4 7 53 54 55 56 133 134 135 267 limited data indicate that 30–100% of an oral dose reaches systemic circulation as unchanged metoclopramide.5 54 56 133 134 135 267 Peak plasma concentration usually attained at 1–2 hours.5 55 267

Orally disintegrating tablets are bioequivalent to the conventional tablets under fasting conditions.278

Following IM administration, absolute bioavailability is 74–96%.7

Following intranasal administration, absolute bioavailability is 47%.277 Absorption is reduced following intranasal versus oral administration; peak concentration, AUC, and time to reach peak concentration are similar following a 15-mg intranasal dose or a 10-mg oral dose.277

Over an intranasal dose range of 10–80 mg, systemic exposure is proportional to dose.277

Onset

Following oral administration, 30–60 minutes for effects on GI tract.7 267

Following IM administration, 10–15 minutes for effects on GI tract.7 267

Following IV administration, 1–3 minutes for effects on GI tract.7 267

Duration

1–2 hours.267

Food

Administration of the orally disintegrating tablets immediately after a high-fat meal did not affect extent of absorption, but decreased peak blood concentration by 17% and increased time to peak concentration to 3 hours (compared with 1.75 hours under fasting conditions).278 Clinical importance of decreased peak concentration is unknown.278

Special Populations

Patients with gastric stasis: Absorption may be delayed or diminished.14

Moderate or severe renal impairment: AUC following oral administration is approximately twice that observed in individuals with normal renal function; in end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis, AUC is approximately 3.5 times that observed in individuals with normal renal function.5 277

Females: AUC and peak concentration following intranasal administration are increased by 34 and 42%, respectively, compared with males.277 Clinical relevance unknown.277

Body weight: Following intranasal administration, lower systemic exposure expected in individuals with higher lean body weight (within range of 34–94 kg).277 Clinical relevance unknown.277

Infants and children: Pharmacodynamics are highly variable; relationship between drug plasma concentrations and pharmacodynamic effects not established.1 267

Infants: Metoclopramide may accumulate in plasma after multiple doses; mean peak plasma concentration was 2-fold higher after 10th dose compared with that after first dose in infants (3.5 weeks–5.4 months of age) with gastroesophageal reflux receiving metoclopramide oral solution.267

Distribution

Extent

In mice, distributed into most body tissues and fluids; high concentrations in GI mucosa, liver, biliary tract, and salivary glands, with lower concentrations in brain, heart, thymus, adrenals, adipose tissue, and bone marrow.4 7

Crosses the placenta.138

Distributed into milk in humans;5 139 140 267 milk concentrations are higher than plasma concentrations 2 hours after oral administration.139 140

Plasma Protein Binding

13–30% (principally albumin).5 7 267

Elimination

Metabolism

Undergoes enzymatic metabolism via oxidation as well as conjugation with glucuronic acid and sulfuric acid in the liver.5 Monodeethylmetoclopramide, a major oxidative metabolite, is formed mainly by CYP2D6, which is subject to genetic variability.5 (See Pharmacogenomics under Cautions.)

Elimination Route

Excreted in urine (85%) as unchanged drug and metabolites7 53 54 133 267 and also in feces (about 5%) within 72 hours following an oral dose.7 53 About 18–20% of an oral dose excreted in urine as unchanged drug within 36 hours.5

Minimally removed by hemodialysis5 129 192 267 or peritoneal dialysis.5 129 267

Half-life

Biphasic; terminal-phase half-life is 2.5–6 hours in adults.5 53 56 57 267 Half-life of 8.1 hours reported following intranasal administration.277

Elimination half-life is about 4.1–4.5 hours in children.267

Special Populations

Renal impairment: Half-life may be prolonged and plasma concentrations increased.5 54 59 142 192 267 (See Absorption: Special Populations, under Pharmacokinetics.)

Severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class C): Average clearance following oral administration is reduced by approximately 50% compared with individuals with normal hepatic function.5 277

Data insufficient to determine whether pharmacokinetics of the drug in children are similar to those in adults.267

Neonates: Reduced clearance, possibly associated with immature renal and hepatic functions present at birth.5 267

Stability

Storage

Nasal

Solution

20–25°C (may be exposed to 15–30°C).277 Discard 4 weeks after opening.277

Oral

Tablets

Tight, light-resistant containers at 20–25°C.5 216

Tablets, Orally Disintegrating

20–25°C.278 Protect from moisture.278 Do not remove from blister pack until immediately before administration.278

Solution

Tight, light-resistant containers at 20–25°C.216 268 269 Protect from freezing.268

Parenteral

Injection

20–25°C.267 Protect from light.267

Following dilution with 5% dextrose, 0.9% sodium chloride, 5% dextrose and 0.45% sodium chloride, Ringer’s, or lactated Ringer’s injection, store for up to 48 hours (without freezing) when protected from light or for up to 24 hours under normal light conditions (i.e., unprotected from light).267

May be stored frozen for up to 4 weeks following dilution with 0.9% sodium chloride injection.267

Degradation occurs if metoclopramide is diluted in 5% dextrose injection and frozen.267

Compatibility

Parenteral

Solution Compatibility124 267

|

Compatible |

|---|

|

Amino acids 2.75%, dextrose 25%, electrolytes124 |

|

Variable |

Manufacturer states that sodium chloride 0.9% is preferred diluent because metoclopramide hydrochloride is most stable in this solution.267

Drug Compatibility

|

Compatible |

|---|

|

Clindamycin phosphate |

|

Mannitol 20% |

|

Meperidine HCl |

|

Meropenem |

|

Morphine sulfate |

|

Multivitamins |

|

Oxycodone HCl |

|

Potassium acetate |

|

Potassium chloride |

|

Potassium phosphates |

|

Ranitidine HCl |

|

Tramadol HCl |

|

Verapamil HCl |

|

Incompatible |

|

Dexamethasone sodium phosphate with lorazepam and diphenhydramine HCl |

|

Erythromycin lactobionate |

|

Fluorouracil |

|

Furosemide |

|

Compatible |

|---|

|

Acetaminophen |

|

Aldesleukin |

|

Amifostine |

|

Aztreonam |

|

Bivalirudin |

|

Bleomycin sulfate |

|

Cangrelor tetrasodium |

|

Ceftaroline fosamil |

|

Ceftolozane sulfate-tazobactam sodium |

|

Ciprofloxacin |

|

Cisatracurium besylate |

|

Cisplatin |

|

Cladribine |

|

Clarithromycin |

|

Cyclophosphamide |

|

Dexmedetomidine HCl |

|

Diltiazem HCl |

|

Docetaxel |

|

Doripenem |

|

Doxapram HCl |

|

Doxorubicin HCl |

|

Droperidol |

|

Etoposide phosphate |

|

Famotidine |

|

Fenoldopam mesylate |

|

Fentanyl citrate |

|

Filgrastim |

|

Fluconazole |

|

Fludarabine phosphate |

|

Fluorouracil |

|

Foscarnet sodium |

|

Gallium nitrate |

|

Gemcitabine HCl |

|

Granisetron HCl |

|

Heparin sodium |

|

Hetastarch in lactated electrolyte injection |

|

Hydromorphone HCl |

|

Idarubicin HCl |

|

Isavuconazonium sulfate |

|

Leucovorin calcium |

|

Levofloxacin |

|

Linezolid |

|

Melphalan HCl |

|

Meperidine HCl |

|

Meropenem |

|

Meropenem-vaborbactam |

|

Methadone HCl |

|

Methotrexate sodium |

|

Mitomycin |

|

Morphine sulfate |

|

Ondansetron HCl |

|

Oxaliplatin |

|

Paclitaxel |

|

Palonosetron HCl |

|

Pemetrexed disodium |

|

Piperacillin sodium–tazobactam sodium |

|

Plazomicin sulfate |

|

Quinupristin-dalfopristin |

|

Remifentanil HCl |

|

Sargramostim |

|

Tacrolimus |

|

Tedizolid phosphate |

|

Telavancin HCl |

|

Teniposide |

|

Thiotepa |

|

Tigecycline |

|

Topotecan HCl |

|

Vinblastine sulfate |

|

Vincristine sulfate |

|

Vinorelbine tartrate |

|

Zidovudine |

|

Incompatible |

|

Allopurinol sodium |

|

Amsacrine |

|

Doxorubicin HCl liposome injection |

|

Furosemide |

|

Variable |

|

Acyclovir sodium |

Actions

-

Complex pharmacology; mechanism(s) of action not fully elucidated; principal effects involve the GI tract and CNS.3 4 5 6 7 8 9 11 12 13 14 125 267

-

At low concentrations in vitro, metoclopramide increases the resting tone and phasic contractile activity of GI smooth muscle.8 16 21

-

Accelerates gastric emptying and intestinal transit from the duodenum to the ileocecal valve by increasing the amplitude and duration of esophageal contractions,4 resting tone of the lower esophageal sphincter,5 7 8 30 39 40 41 42 267 and amplitude and tone of gastric (especially antral) contraction 5 7 9 16 25 33 37 38 43 44 267 and by relaxing the pyloric sphincter and the duodenal bulb, while increasing peristalsis of the duodenum and jejunum.5 7 25 33 38 43 45 48 49 267

-

Unlike nonspecific cholinergic-like stimulation of upper GI smooth muscle, the stimulant effects of metoclopramide on GI smooth muscle coordinate gastric, pyloric, and duodenal motor activity.25 33 38

-

Precise mechanism of antiemetic action is unclear.2 4 8 52 60 61 103 125 219 220 221 222 223 224 225 226 227 Directly affects medullary chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), apparently by blocking dopamine receptors;2 4 8 52 60 61 103 125 219 220 221 222 223 224 225 226 227 increases CTZ threshold and decreases sensitivity of visceral nerves that transmit impulses from GI tract to vomiting center;4 and enhances gastric emptying (believed to minimize stasis that precedes vomiting).4 125 Also may inhibit serotonin (5-HT3) receptors (at relatively high doses).219 220 223 224 225 226 227

-

Produces varying degrees of sedation and lethargy.4

-

May cause extrapyramidal reactions4 5 267 and worsen symptoms in patients with parkinsonian syndrome.5 130 158 160 267

Advice to Patients

-

Importance of providing patient or caregiver with a copy of the manufacturer’s medication guide.5 267 Importance of instructing patient or caregiver to read and understand the contents of the medication guide before initiating therapy and each time the prescription is refilled.5 267

-

Importance of informing patients that oral and intranasal formulations of metoclopramide are recommended for use in adults only.5 268 269 277 278

-

Importance of instructing patients receiving intranasal metoclopramide therapy on appropriate use of the metered-dose inhaler and providing them with a copy of the manufacturer's instructions for use.277

-

Risk of tardive dyskinesia.5 267 Importance of contacting clinician immediately if new, abnormal, involuntary, or uncontrollable muscle movements occur (e.g., lip smacking, chewing, puckering mouth, frowning, scowling, tongue protrusion, blinking, eye movements, arm and leg shaking).5 267 Importance of not taking metoclopramide for >12 weeks.5

-

Risk of NMS.5 Importance of contacting clinician immediately if signs or symptoms of NMS (e.g., high fever, stiff muscles, difficulty thinking, fast or uneven heartbeat, increased sweating) occur.5

-

Risk of dystonic reactions, parkinsonian symptoms, or akathisia.5 Importance of contacting clinician immediately if such reactions occur.5

-

Risk of depression and/or suicidality.5 Importance of contacting clinician immediately if depression or suicidality occurs.5

-

Potential for drowsiness or dizziness to occur.5

-

Potential for metoclopramide to impair mental alertness or physical coordination; avoid driving or operating machinery until effects on individual are known.5 267 Advise patient that alcohol, opiate analgesics, sedatives or hypnotics, anxiolytic agents, other CNS depressants, and other drugs that cause extrapyramidal symptoms may enhance such impairment.5

-

For patients receiving metoclopramide nasal solution, importance of not repeating a dose if uncertain whether the spray entered the nostril and of not administering an extra dose or a double dose to make up for a missed dose; instead, administer the next dose at the regularly scheduled time.277

-

Importance of informing patients with phenylketonuria that metoclopramide orally disintegrating tablets contain aspartame.278

-

Importance of informing clinicians of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs, as well as any concomitant illnesses.5 267 Advise patient that concomitant use of metoclopramide with many other drugs may precipitate or worsen tardive dyskinesia, extrapyramidal symptoms, NMS, and CNS depression.5

-

Importance of women informing clinicians if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.5 267

-

Importance of informing patients of other important precautionary information.5 267 (See Cautions.)

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nasal |

Solution |

15 mg (of metoclopramide) per metered spray |

Gimoti |

Evoke |

|

Oral |

Solution |

5 mg (of metoclopramide) per 5 mL* |

Metoclopramide Hydrochloride Oral Solution |

|

|

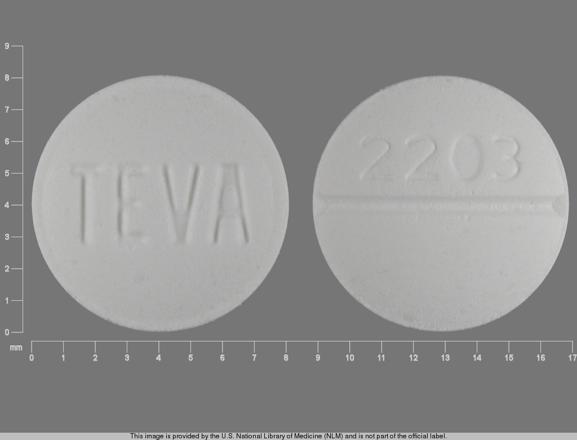

Tablets |

5 mg (of metoclopramide)* |

Metoclopramide Hydrochloride Tablets |

||

|

Reglan |

ANI |

|||

|

10 mg (of metoclopramide)* |

Metoclopramide Hydrochloride Tablets |

|||

|

Reglan (scored) |

ANI |

|||

|

Tablets, orally disintegrating |

5 mg (of metoclopramide)* |

Metoclopramide Hydrochloride Orally Disintegrating Tablets |

||

|

10 mg (of metoclopramide)* |

Metoclopramide Hydrochloride Orally Disintegrating Tablets |

|||

|

Parenteral |

Injection |

5 mg (of metoclopramide) per mL* |

Metoclopramide Hydrochloride Injection |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2024, Selected Revisions March 15, 2021. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

1. Justin-Besancon L, Laville C, Thominet M. Le métoclopramide et ses homologues: introduction è leur étude biologique. CR Acad Sci (Paris). 1964; 25:4384-6.

2. Jenner P, Marsden CD. The substituted benzamides: a novel class of dopamine antagonists. Life Sci. 1979; 25:479-85. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/40086?dopt=AbstractPlus

3. Schulze-Delrieu K. Metoclopramide. N Engl J Med. 1981; 305:28-33. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7015140?dopt=AbstractPlus

4. Pinder RM, Brogden RN, Sawyer PR et al. Metoclopramide: a review of its pharmacological properties and clinical uses. Drugs. 1976; 12:81-131. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/786607?dopt=AbstractPlus

5. ANI Pharmaceuticals. Metoclopramide hydrochloride tablets prescribing information. Baudette, MN; 2017 Aug.

6. Robinson OPW. Metoclopramide: a new pharmacological approach. Postgrad Med J. 1973; 49(Suppl 4):9-12.

7. AH Robins Company, Inc. Drug monograph. Reglan injectable, Reglan tablets. Richmond, VA; 1981 Apr.

8. Schulze-Delrieu K. Metoclopramide. Gastroenterology. 1979; 77:768-79. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/223940?dopt=AbstractPlus

9. Albibi R, McCallum RW. Metoclopramide: pharmacology and clinical application. Ann Intern Med. 1983; 98:86-95. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6336644?dopt=AbstractPlus

10. Windholz M, ed. The Merck index. 10th ed. Rahway, NJ: Merck & Co, Inc; 1983:880.

11. Smith MA, Salter FJ. Metoclopramide (Reglan, AH Robins). Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1980; 14:169-76.

12. Hurwitz A, Rhodes JB. Metoclopramide: pharmacology and clinical use. Hosp Formul. 1981; 16:638-46.

13. Ponte CD, Nappi JM. Review of a new gastrointestinal drug: metoclopramide. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1981; 38:829-33. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7018232?dopt=AbstractPlus

14. Anon. Metoclopramide (Reglan). Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1982; 24:67-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7087890?dopt=AbstractPlus

15. Jacoby HI, Brodie DA. Gastrointestinal actions of metoclopramide: an experimental study. Gastroenterology. 1967; 52:676-84. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4960492?dopt=AbstractPlus

16. Eisner M. Gastrointestinal effects of metoclopramide in man: in vitro experiments with human smooth muscle preparations. Br Med J. 1968; 4:679-80. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1912809&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5723387?dopt=AbstractPlus

17. Johnson AG. The action of metoclopramide on the canine stomach, duodenum, and gallbladder. Br J Surg. 1969; 56:696-71. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5808392?dopt=AbstractPlus

18. Hay AM. The mechanism of action of metoclopramide. Gut. 1975; 16:403-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1140672?dopt=AbstractPlus

19. Thorner MO. Dopamine is an important neurotransmitter in the autonomic nervous system. Lancet. 1975; 1:662-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/47084?dopt=AbstractPlus

20. Cohen S, DiMarino AJ. Mechanism of action of metoclopramide on opossum lower esophageal sphincter muscle. Gastroenterology. 1976; 71:996-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/992283?dopt=AbstractPlus

21. Okwuasaba FK, Hamilton JT. The effect of metoclopramide on intestinal muscle responses and the peristaltic reflex in vitro. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1976; 54:393-404. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/953868?dopt=AbstractPlus

22. Hay AM. Pharmacological analysis of the effects of metoclopramide on the guinea pig isolated stomach. Gastroenterology. 1977; 72:864-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/849817?dopt=AbstractPlus

23. Hay AM, Man WK. Effect of metoclopramide on guinea pig stomach: critical dependence on intrinsic stores of acetylcholine. Gastroenterology. 1979; 76:492-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/428704?dopt=AbstractPlus

24. Birtley RDN, Baines MW. The effects of metoclopramide on some isolated intestinal preparations. Postgrad Med J. 1973; 49(Suppl 4):13-8.

25. Johnson AG. Gastroduodenal motility and synchronization. Postgrad Med J. 1973; 49(Suppl 4):29-33. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2495366&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4199925?dopt=AbstractPlus

26. Beani L, Bianchi C, Crema C. Effects of metoclopramide on isolated guinea-pig colon: 1. Peripheral sensitization to acetylcholine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1970; 12:320-31. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5495440?dopt=AbstractPlus

27. Valenzuela JE. Dopamine as a possible neurotransmitter in gastric relaxation. Gastroenterology. 1976; 71:1019-22. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11140?dopt=AbstractPlus

28. de Carle DJ, Christensen J. A dopamine receptor in esophageal smooth muscle of the opossum. Gastroenterology. 1976; 70:216-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2511?dopt=AbstractPlus

29. Connell AM, George JD. Effect of metoclopramide on gastric function in man. Gut. 1969; 10:678-80. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1552902&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4897625?dopt=AbstractPlus

30. McCallum RW, Kline MM, Curry N et al. Comparative effects of metoclopramide and bethanecol on lower esophageal sphincter pressure in reflux patients. Gastroenterology. 1975; 68:1114-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1092585?dopt=AbstractPlus

31. Stadaas J, Aune S. The effect of metoclopramide (Primperan) on gastric motility before and after vagotomy in man. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1971; 6:17-21. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5100064?dopt=AbstractPlus

32. Fox S, Behar J. Pathogenesis of diabetic gastroparesis: a pharmacologic study. Gastroenterology. 1980; 78:757-63. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7353762?dopt=AbstractPlus

33. Johnson AG. The effect of metoclopramide on gastroduodenal and gallbladder contractions. Gut. 1971; 12:158-63. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1411528&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5548563?dopt=AbstractPlus

34. Baumann HW, McCallum RW, Sturdevant RAL. Metoclopramide: a possible antagonist of dopamine in the esophagus of man. Gastroenterology. 1976; 70:682.

35. Baumann HW, Sturdevant RAL, McCallum RW. L-dopa inhibits metoclopramide stimulation of the lower esophageal sphincter in man. Dig Dis Sci. 1979; 24:289-95. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/378623?dopt=AbstractPlus

36. Berkowitz DM, McCallum RW. Interaction of levodopa and metoclopramide on gastric emptying. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1980; 27:414-20. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7357798?dopt=AbstractPlus

37. Hancock BD, Bowen-Jones E, Dixon R et al. The effect of metoclopramide on gastric emptying of solid meals. Gut. 1974; 15:462-7. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1413012&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4605245?dopt=AbstractPlus

38. Eisner M. Effect of metoclopramide on gastrointestinal motility in man: a manometric study. Am J Dig Dis. 1971; 16:409-19. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4931153?dopt=AbstractPlus

39. Behar J, Biancani P. Effect of oral metoclopramide on gastroesophageal reflux in the post-cibal state. Gastroenterology. 1976; 70:331-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/765184?dopt=AbstractPlus

40. Cohen S, Morris DW, Schoen HJ et al. The effect of oral and intravenous metoclopramide on human lower esophageal sphincter pressure. Gastroenterology. 1976; 70:484-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/767194?dopt=AbstractPlus

41. Wallin L, Boesby S, Madsen T. Effect of metoclopramide on esophageal peristalsis and gastroesophageal sphincter pressure. Scan J Gastroenterol. 1979; 14:923-7.

42. Stanciu C, Bennett JR. Metoclopramide in gastroesophageal reflux. Gut. 1973; 14:275-9. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1412597&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4706908?dopt=AbstractPlus

43. James WB, Hume R. Action of metoclopramide on gastric emptying and small bowel transit time. Gut. 1968; 9:203-5. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1552556&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5655030?dopt=AbstractPlus

44. Perkel MS, Moore C, Hersch T et al. Metoclopramide therapy in patients with delayed gastric emptying: a randomized double-blind study. Dig Dis Sci. 1979; 24:662-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/385260?dopt=AbstractPlus

45. Pearson MC, Edwards D, Tate A et al. Comparison of the effects of oral and intravenous metoclopramide on the small bowel. Postgrad Med J. 1973; 49(Suppl 4):47-50.

46. Katevuo K, Kauto J, Philajamaki K. The effect of metoclopramide on the contraction of the human gallbladder. Invest Radiol. 1975; 10:197-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1132949?dopt=AbstractPlus

47. Lipton AB, Knauer CM. Pseudo-obstruction of the bowel. Therapeutic trial of metoclopramide. Am J Dig Dis. 1977; 22:263-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/320866?dopt=AbstractPlus

48. Johnson AG. The action of metoclopramide on human gastroduodenal motility. Gut. 1971; 12:421-6. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1411660&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4996971?dopt=AbstractPlus

49. Malagelada JR, Ress WDW, Mazzotta LJ et al. Gastric motor abnormalities in diabetic and postvagotomy gastroparesis: effect of metoclopramide and bethanecol. Gastroenterology. 1980; 78:286-93. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7350052?dopt=AbstractPlus

50. Lafranchi GA, Marzio L, Cortinic C et al. Effect of dopamine in gastric motility in man: evidence for specific receptors. In: Duthie HL, ed. Gastrointestinal motility in health and disease. Lancaster, England: MTP Publishers; 1977:161-72.

51. Sinnett HD, Leathard HL, Johnson AG. The effect of dopamine on human gastric smooth muscle. In: Weinbeck, ed. Motility of the digestive tract. New York: Raven Press; 1982:347-54.

52. Peroutka SJ, Snyder SH. Antiemetics: neurotransmitter receptor binding predicts therapeutic actions. Lancet. 1982; 1:658-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6121969?dopt=AbstractPlus

53. Teng L, Bruce RB, Dunning LK. Metoclopramide metabolism and determination by high-pressure liquid chromatography. J Pharm Sci. 1977; 66:1615-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/915740?dopt=AbstractPlus

54. Bateman DN, Davies DS. Pharmacokinetics of metoclopramide. Lancet. 1979; 1:166. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/84196?dopt=AbstractPlus

55. Schuppan D, Schmidt I, Heller M. Preliminary pharmacokinetics of metoclopramide in humans. Plasma levels following a single oral and intravenous dose. Arzneimittelforschung. 1979; 29:151-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/582108?dopt=AbstractPlus

56. Graffner C, Lagerstrom P, Lundborg P et al. Pharmacokinetics of metoclopramide intravenously and orally determined by liquid chromatography. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1979; 8:469-74. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1429814&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/508553?dopt=AbstractPlus

57. Bateman DN, Kahn C, Mashiter K et al. Pharmacokinetic and concentration-effect studies with intravenous metoclopramide. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1978; 6:401-7. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1429552&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/728283?dopt=AbstractPlus

58. Caralps A. Metoclopramide and renal failure. Lancet. 1979; 1:554. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/85136?dopt=AbstractPlus

59. Bateman DN, Gokal R, Dodd RP et al. The pharmacokinetics of single doses of metoclopramide in renal failure. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1981; 19:437-41. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7250177?dopt=AbstractPlus

60. Dolphin A, Jenner P, Marsden CD et al. Pharmacological evidence for cerebral dopamine receptor blockade by metoclopramide in rodents. Psychopharmacologica. 1975; 41:133-8.

61. Cannon JG. Chemistry of dopaminergic agonists. Adv Neurol. 1975; 9:177-83. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1146652?dopt=AbstractPlus

62. Tarsy D, Parkes JD, Marsden CD. Metoclopramide and pimozide in Parkinson’s disease and levodopa-induced dyskinesias. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1975; 38:331-5. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=491929&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1095689?dopt=AbstractPlus

63. Thorburn CW, Sowton E. The haemodynamic effects of metoclopramide. Postgrad Med J. 1973; 49(Suppl 4):22-4.

64. Day MD, Blower PR. Cardiovascular dopamine receptor stimulation antagonized by metoclopramide. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1975; 27:276-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/239122?dopt=AbstractPlus

65. Masala A, Delitala G, Alagna S et al. Effect of dopaminergic blockade on the secretion of growth hormone and prolactin in man. Metabolism. 1978; 27:921-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/672613?dopt=AbstractPlus

66. Healy DL, Burger HG. Increased prolactin and thyrotrophin secretion following oral metoclopramide: dose-response relationships. Clin Endocrinol. 1977; 7:195-8.

67. McNeilly AS, Thomer MO, Volans G et al. Metoclopramide and prolactin. Br Med J. 1974; 2:729-30. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1611149&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4852857?dopt=AbstractPlus

68. Sowers JR, McCallum RW, Hershman JM et al. Comparison of metoclopramide with other dynamic tests of prolactin secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1976; 43:679-81. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/821965?dopt=AbstractPlus

69. Norbiato G, Bevilacqua M, Raggi U. Metoclopramide increases plasma aldosterone concentration in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1977; 45:1313-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/591626?dopt=AbstractPlus

70. Cohen HN, Hay ID, Beastall GH et al. Metoclopramide induced growth hormone release in hypogonadal males. Clin Endocrinol. 1979; 11:95-7.

71. North RH, McCallum RW, Contino C et al. Tonic dopaminergic suppression of plasma aldosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1980; 51:64-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7380993?dopt=AbstractPlus

72. Sowers JR, Sharp B, McCallum RW. Effect of domperidone, an extracerebral inhibitor of dopamine receptors, on thyrotropin, prolactin, renin, aldosterone and 18-hydroxycorticosterone in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982; 54:869-71. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7037817?dopt=AbstractPlus

73. Plouin PF, Menard J, Corvol P. Hypertensive crisis in a patient with phaeochromocytoma given metoclopramide. Lancet. 1976; 2:1357-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/63830?dopt=AbstractPlus

74. Rampton DS. Hypertensive crisis in a patient given Sinemet, metoclopramide, and amitriptyline. Br Med J. 1977; 2:607-8. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1631513&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/901999?dopt=AbstractPlus

75. Scanlon MF, Weightman DR, Mora B et al. Evidence for dopaminergic control of thyrotrophin secretion in man. Lancet. 1977; 2:421-3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/70641?dopt=AbstractPlus

76. Brownlee M, Kroopf SS. Metoclopramide for gastroparesis diabeticorum. N Engl J Med. 1974; 291:1256-8.

77. Longstreth GF, Malagelada JR, Kelly K. Metoclopramide stimulation of gastric motility and emptying in diabetic gastroparesis. Ann Intern Med. 1977; 86:195-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/835945?dopt=AbstractPlus

78. Hartong WA, Moore J, Booth JP. Metoclopramide in diabetic gastroparesis. Ann Intern Med. 1977; 86:826. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/869367?dopt=AbstractPlus

79. Berkowitz DM, Metzger WH, Sturdevant RAL. Oral metoclopramide in diabetic gastroparesis and in chronic gastric retention after gastric surgery. Gastroenterology. 1976; 70:863.

80. Snape WJ, Battle WM, Schwartz SS et al. Metoclopramide to treat gastroparesis due to diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 1982; 96:444-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7065559?dopt=AbstractPlus

81. Carey RM, Thorner MO, Ortt EM. Effects of metoclopramide and bromocriptine on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in man: dopaminergic control of aldosterone. J Clin Invest. 1979; 63:727-35. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=372008&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/438333?dopt=AbstractPlus

82. Aono T, Shioji T, Kinugasa T et al. Clinical and endocrinological analyses of patients with galactorrhea and menstrual disorders due to sulpiride or metoclopramide. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1978; 47:675-80. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/122411?dopt=AbstractPlus

83. Campbell IW, Heading RC, Tothill P et al. Gastric emptying in diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Gut. 1977; 18:462-7. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1411495&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/873328?dopt=AbstractPlus

84. Saltzman M, Meyer C, Callachan C et al. Effect of metoclopramide on chronic gastric stasis in diabetic and post-gastric surgery patients. Gastroenterology. 1981; 80:1268.

85. Kassander P. Asymptomatic gastric retention in diabetics (gastroparesis diabeticorum). Ann Intern Med. 1958; 48:797-812. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13521605?dopt=AbstractPlus

86. Scarpello JHB, Baber DC, Hague RV et al. Gastric emptying of solid meals in diabetics. Br Med J. 1976; 2:671-3. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1688343&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/974530?dopt=AbstractPlus

87. AH Robins Company, Inc. Diabetic gastroparesis: a literature review. Richmond, VA; 1979 Oct.

88. AH Robins Company, Inc. The use of Reglan tablets in diabetic gastroparesis. Richmond, VA; 1979 Sep.

89. AH Robins Company, Inc. A multi-center placebo-controlled clinical trial of Reglan tablets in diabetic gastroparesis. Richmond, VA; 1979 Sep.

90. Robinson OPW. Metoclopramide: side effects and safety. Postgrad Med J. 1973; 49(Suppl 4):77-80. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2495349&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4729186?dopt=AbstractPlus

91. Casteels-Van Daele M, Jaeken J, Van der Schueren P et al. Dystonic reactions in children caused by metoclopramide. Arch Dis Child. 1970; 45:130-3. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2020385&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5440179?dopt=AbstractPlus

92. Cochlin DL. Dystonic reactions due to metoclopramide and phenothiazines resembling tetanus. Br J Clin Pract. 1974; 28:201-2. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4447767?dopt=AbstractPlus

93. Lavy S, Melamed E, Penchas S. Tardive dyskinesia associated with metoclopramide. Br Med J. 1978; 1:77-8. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1602611&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/620205?dopt=AbstractPlus

94. Kataria M, Traub M, Marsden CD. Extrapyramidal side effects of metoclopramide. Lancet. 1978; 2:1254-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/82759?dopt=AbstractPlus

95. Shaklai M, Pinkhas J, Devries A. Metoclopramide and cardiac arrhythmia. Br Med J. 1974; 2:385.

96. Agabati-Rosie E, Alicandri CL, Corea L. Hypertensive crisis in patients with phaeochromocytoma given metoclopramide. Lancet. 1977; 1:600. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/65683?dopt=AbstractPlus

97. Gralla RJ, Squillante AE, Steele N et al. Phase I intravenous trial of the antiemetic metoclopramide in patients receiving cis-platinum (DDP). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1980; 21:350.

98. Gralla RJ, Itri LM, Pisko SE et al. Antiemetic efficacy of high-dose metoclopramide: randomized trials with placebo and prochlorperazine in patients with chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 1981; 305:905-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7024807?dopt=AbstractPlus

99. Strum SB, McDermed JE, Opfell RW et al. Intravenous metoclopramide: an effective antiemetic in cancer chemotherapy. JAMA. 1982; 247:2683-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7043002?dopt=AbstractPlus

100. Carr B, Palone B, Pertrand M et al. A double-blind comparison of metoclopramide (MCP) and proclorperazine (PCP) for cis-platinum (DDP) induced emesis. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1982; 1:66.

101. Daniels M, Belt RJ. High dose metoclopramide as an antiemetic for patients receiving chemotherapy with cis-platinum. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1982; 9:20-2. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6921788?dopt=AbstractPlus

102. Gralla RJ, Tyson LB, Clark RA et al. Antiemetic trials with high dose metoclopramide superiority over THC, and preservation of efficacy in subsequent chemotherapy courses. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1982; 1:58.

103. Gralla RJ. Metoclopramide: a review of antiemetic trials. Drugs. 1983; 25:63-73. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6682376?dopt=AbstractPlus

104. Seigel LJ, Longo DL. The control of chemotherapy-induced emesis. Ann Intern Med. 1981; 95:352-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7023313?dopt=AbstractPlus

105. Moshal MG. A rapid jejunal biopsy technique aided by metoclopramide: a double-blind trial with 50 patients. Postgrad Med J. 1973; 49(Suppl 4):87-9.

106. Arvanitakis C, Gonzalez G, Rhodes JB. The role of metoclopramide in peroral jejunal biopsy: a controlled randomized trial. Am J Dig Dis. 1976; 21:880-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1015496?dopt=AbstractPlus

107. Cristie DL, Ament ME. A double blind crossover study of metoclopramide versus placebo for facilitating passage of multipurpose biopsy tube. Gastroenterology. 1976; 71:726-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/786773?dopt=AbstractPlus

108. Sallan SE, Cronin C, Zelen M et al. Antiemetics in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer: a randomized comparison of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and prochlorperazine. N Engl J Med. 1980; 302:135-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6985702?dopt=AbstractPlus

109. Bolin TD. The facilitation of duodenal intubation with metoclopramide. Med J Aust. 1969; 1:1078-9.

110. Margieson GR, Sorby WA, Williams HBL. The action of metoclopramide on gastric emptying: a radiological assessment. Med J Aust. 1966; 2:1272-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5957603?dopt=AbstractPlus

111. McCallum RW, Berkowitz DM, Lerner E. Gastric emptying in patients with gastroesophageal reflux. Gastroenterology. 1981; 80:285-91. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7450419?dopt=AbstractPlus

112. McCallum RW, Ippoliti AF, Cooney C et al. A controlled trial of metoclopramide in symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux. N Engl J Med. 1977; 296:354-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/319356?dopt=AbstractPlus

113. Stadaas JO, Aune S. Clinical trial of metoclopramide in postvagotomy gastric stasis. Arch Surg. 1972; 104:684-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4554726?dopt=AbstractPlus

114. Metzger W, Cano R, Sturdevant RAL. Effect of metoclopramide in chronic gastric retention after gastric surgery. Gastroenterology. 1975; 68:954.

115. McCallum RW, Saltzman M, Meyer C. Effect of metoclopramide in chronic gastric retention after gastric surgery. Clin Res. 1980; 28:765A.

116. Winnan J, Avella J, Callachan C et al. Double-blind trial of metoclopramide versus placebo-antacid in symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux. Gastroenterology. 1980; 78:1292.

117. Bright-Asare P, El-Bassoussi M. Cimetidine, metoclopramide or placebo in the treatment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1980; 2:149-56. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7002998?dopt=AbstractPlus

118. Gosselin RE, Hodge HC, Smith RP et al. Clinical toxicology of commercial products: acute poisoning. 5th ed. Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkins Co; 1984:I-10.

119. Johnson BF, O’Grady J, Bye C. The influence of digoxin particle size on absorption of digoxin and the effect of propantheline and metoclopramide. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1978; 5:465-7. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1429356&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/656287?dopt=AbstractPlus

120. Mearrick PT, Wade DN, Birkett DJ et al. Metoclopramide gastric emptying and l-dopa absorption. Aust N Z J Med. 1974; 4:144-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4528645?dopt=AbstractPlus

121. Wade A, ed. Martindale: the extra pharmacopoeia. 28th ed. London: The Pharmaceutical Press; 1982:964.

122. Board AW (AH Robins Company, Richmond, VA): Personal communication; 1983 Jul 29.

123. Anon. Compatibility chart for Reglan (metoclopramide hydrochloride) injectable 5 mg/ml. AH Robins Pharmaceutical Division, Richmond, VA. Publication No. Reg H9CT; 1983 Oct.

124. ASHP injectable drug information. Metoclopramide. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; Updated 2020 May 1. Accessed 2020 Sep 28. https://injectables.ashp.org

125. Harrington RA, Hamilton CW, Brogden RN et al. Metoclopramide: an updated review of its pharmacological properties and clinical use. Drugs. 1983; 25:451-94. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6345129?dopt=AbstractPlus

126. Battle WM, Snape WJ Jr, Alavi A et al. Colonic dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology. 1980; 79:1217-21. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7439629?dopt=AbstractPlus

127. Battle WM, Snape WJ Jr, Wright S et al. Abnormal colonic motility in progressive systemic sclerosis. Ann Intern Med. 1981; 94:749-52. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7235416?dopt=AbstractPlus