Losartan (Monograph)

Brand name: Cozaar

Drug class: Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonists

VA class: CV805

Chemical name: 2-Butyl-4-chloro-1-[[2′-(1H-tetrazol-5-yl)[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl]-methyl]-1H-imidazole-5-methanol monopotassium salt

Molecular formula: C22H23ClN6O

CAS number: 124750-99-8

Warning

Introduction

Angiotensin II receptor (AT1) antagonist (i.e., angiotensin II receptor blocker, ARB).1 2

Uses for Losartan

Hypertension

Management of hypertension (alone or in combination with other classes of antihypertensive agents, including diuretics).1 2 1200

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists are recommended as one of several preferred agents for the initial management of hypertension according to current evidence-based hypertension guidelines; other preferred options include ACE inhibitors, calcium-channel blockers, and thiazide diuretics.501 502 503 504 1200 While there may be individual differences with respect to recommendations for initial drug selection and use in specific patient populations, current evidence indicates that these antihypertensive drug classes all generally produce comparable effects on overall mortality and cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and renal outcomes.501 502 503 504 1200 1213

Individualize choice of therapy; consider patient characteristics (e.g., age, ethnicity/race, comorbidities, cardiovascular risk) as well as drug-related factors (e.g., ease of administration, availability, adverse effects, cost).501 502 503 504 515 1200 1201

A 2017 ACC/AHA multidisciplinary hypertension guideline classifies BP in adults into 4 categories: normal, elevated, stage 1 hypertension, and stage 2 hypertension.1200 (See Table 1.)

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13-115.

Individuals with SBP and DBP in 2 different categories (e.g., elevated SBP and normal DBP) should be designated as being in the higher BP category (i.e., elevated BP).

|

Category |

SBP (mm Hg) |

DBP (mm Hg) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Normal |

<120 |

and |

<80 |

|

Elevated |

120–129 |

and |

<80 |

|

Hypertension, Stage 1 |

130–139 |

or |

80–89 |

|

Hypertension, Stage 2 |

≥140 |

or |

≥90 |

The goal of hypertension management and prevention is to achieve and maintain optimal control of BP.1200 However, the BP thresholds used to define hypertension, the optimum BP threshold at which to initiate antihypertensive drug therapy, and the ideal target BP values remain controversial.501 503 504 505 506 507 508 515 523 526 530 1200 1201 1207 1209 1222 1223 1229

The 2017 ACC/AHA hypertension guideline generally recommends a target BP goal (i.e., BP to achieve with drug therapy and/or nonpharmacologic intervention) <130/80 mm Hg in all adults regardless of comorbidities or level of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.1200 In addition, an SBP goal of <130 mm Hg is recommended for noninstitutionalized ambulatory patients ≥65 years of age with an average SBP of ≥130 mm Hg.1200 These BP goals are based upon clinical studies demonstrating continuing reduction of cardiovascular risk at progressively lower levels of SBP.1200 1202 1210

Previous hypertension guidelines generally have based target BP goals on age and comorbidities.501 504 536 Guidelines such as those issued by the JNC 8 expert panel generally have targeted a BP goal of <140/90 mm Hg regardless of cardiovascular risk and have used higher BP thresholds and target BPs in elderly patients501 504 536 compared with those recommended by the 2017 ACC/AHA hypertension guideline.1200

Some clinicians continue to support previous target BPs recommended by JNC 8 due to concerns about the lack of generalizability of data from some clinical trials (e.g., SPRINT study) used to support the current ACC/AHA hypertension guideline and potential harms (e.g., adverse drug effects, costs of therapy) versus benefits of BP lowering in patients at lower risk of cardiovascular disease.1222 1223 1224 1229

Consider potential benefits of hypertension management and drug cost, adverse effects, and risks associated with the use of multiple antihypertensive drugs when deciding a patient’s BP treatment goal.1200 1220 1229

For decisions regarding when to initiate drug therapy (BP threshold), the 2017 ACC/AHA hypertension guideline incorporates underlying cardiovascular risk factors.1200 1207 ASCVD risk assessment recommended by ACC/AHA for all adults with hypertension.1200

ACC/AHA currently recommend initiation of antihypertensive drug therapy in addition to lifestyle/behavioral modifications at an SBP ≥140 mm Hg or DBP ≥90 mm Hg in adults who have no history of cardiovascular disease (i.e., primary prevention) and a low ASCVD risk (10-year risk <10%).1200

For secondary prevention in adults with known cardiovascular disease or for primary prevention in those at higher risk for ASCVD (10-year risk ≥10%), ACC/AHA recommend initiation of antihypertensive drug therapy at an average SBP ≥130 mm Hg or an average DBP ≥80 mm Hg.1200

Adults with hypertension and diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease (CKD), or age ≥65 years are assumed to be at high risk for cardiovascular disease; ACC/AHA state that such patients should have antihypertensive drug therapy initiated at a BP ≥130/80 mm Hg.1200

In stage 1 hypertension, experts state that it is reasonable to initiate drug therapy using the stepped-care approach in which one drug is initiated and titrated and other drugs are added sequentially to achieve the target BP.1200 Initiation of antihypertensive therapy with 2 first-line agents from different pharmacologic classes recommended in adults with stage 2 hypertension and average BP >20/10 mm Hg above BP goal.1200

Black hypertensive patients generally tend to respond better to monotherapy with calcium-channel blockers or thiazide diuretics than to angiotensin II receptor antagonists.501 504 1200 However, the combination of an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor antagonist with a calcium-channel blocker or thiazide diuretic produces similar BP lowering in black patients as in other racial groups.1200

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists or ACE inhibitors may be particularly useful in hypertensive patients with diabetes mellitus or CKD; angiotensin II receptor antagonists also may be preferred, as an alternative to ACE inhibitors, in hypertensive patients with heart failure or ischemic heart disease and/or post-MI.501 502 504 523 524 527 534 535 536 543 1200 1214 1215

Prevention of Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality

Reduction of the risk of stroke in patients with hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy.1 2 53

Evidence suggests that the benefit associated with such losartan-based antihypertensive therapy does not apply to black patients.1 20 53

Preliminary evidence suggests that aspirin therapy at baseline in patients receiving losartan may reduce the risk of combined cardiovascular death, stroke, and acute MI compared with aspirin therapy at baseline in patients receiving atenolol.54

Diabetic Nephropathy

Management of diabetic nephropathy manifested by elevated Scr and proteinuria (urinary albumin to creatinine ratio ≥300 mg/g) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension.1 33

A recommended agent in the management of patients with diabetes mellitus and persistent albuminuria who have modestly elevated (30–300 mg/24 hours) or higher (>300 mg/24 hours) levels of urinary albumin excretion; slows rate of progression of renal disease in such patients.38 39 41 42 43 535 536 1232

Heart Failure

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists have been used in the management of heart failure† [off-label].524 528 800

Because of their established benefits, ACE inhibitors have been the preferred drugs for inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAA) system in patients with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF); 524 however, some evidence indicates that therapy with an ACE inhibitor (enalapril) may be less effective than angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) therapy (e.g., sacubitril/valsartan) in reducing cardiovascular death and heart failure-related hospitalization.701 702 703 800

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists may be used as an alternative for those patients in whom an ACE inhibitor or ARNI is inappropriate.524 800

ACCF, AHA, and the Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA) recommend that patients with chronic symptomatic heart failure and reduced LVEF (NYHA class II or III) who are able to tolerate an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor antagonist be switched to therapy containing an ARNI to further reduce morbidity and mortality.800

Related/similar drugs

amlodipine, lisinopril, metoprolol, furosemide, hydrochlorothiazide, atenolol, enalapril

Losartan Dosage and Administration

General

BP Monitoring and Treatment Goals

-

Monitor BP regularly (i.e., monthly) during therapy and adjust dosage of the antihypertensive drug until BP controlled.1200

-

If unacceptable adverse effects occur, discontinue drug and initiate another antihypertensive agent from a different pharmacologic class.1216

-

If adequate BP response not achieved with a single antihypertensive agent, either increase dosage of single drug or add a second drug with demonstrated benefit and preferably a complementary mechanism of action (e.g., calcium-channel blocker, thiazide diuretic).1200 1216 Many patients will require at least 2 drugs from different pharmacologic classes to achieve BP goal; if goal BP still not achieved with 2 antihypertensive agents, add a third drug.1200 1216 1220

Administration

Oral Administration

Administer losartan orally once or twice daily without regard to meals.1 2 Administer losartan as extemporaneously prepared oral suspension in patients unable to swallow tablets.1 Administer losartan in fixed combination with hydrochlorothiazide once daily without regard to meals.2

Reconstitution

Preparation of extemporaneous suspension containing losartan potassium 2.5 mg/mL: Add 10 mL of purified water to a 240-mL polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottle containing ten 50-mg tablets of losartan potassium; shake contents for ≥2 minutes.1 Allow concentrated suspension to stand for 60 minutes following reconstitution, then shake for an additional minute.1 Prepare a mixture containing equal parts (by volume) of syrup (Ora-Sweet) and suspending vehicle (Ora-Plus) separately.1 Dilute the concentrated suspension of losartan potassium with 190 mL of the Ora-Sweet and Ora-Plus mixture; shake the container an additional minute to disperse ingredients.1 Shake suspension before dispensing each dose.1

Dosage

Available as losartan potassium; dosage expressed in terms of the salt.1 2

Pediatric Patients

Hypertension

Oral

Children ≥6 years of age: Initially, 0.7 mg/kg (up to 50 mg) once daily.1 1150 Dosage may be increased every 2–4 weeks until BP controlled, maximum dosage reached (maximum dosage of 1.4 mg/kg or 100 mg daily), or adverse effects occur.1 1150 .

Adults

Hypertension

Losartan Therapy

OralManufacturer recommends initial dosage of 50 mg once daily in adults without intravascular volume depletion.1 In adults with depletion of intravascular volume, the usual initial dosage is 25 mg once daily.1

Usual dosage: Manufacturer states 25–100 mg daily, given in 1 dose or 2 divided doses; no additional therapeutic benefit with higher dosages.1 Some experts state 50–100 mg daily, given in 1 dose or 2 divided doses.1200

If effectiveness diminishes toward end of dosing interval in patients treated once daily, consider increasing dosage or administering drug in 2 divided doses.1

Losartan/Hydrochlorothiazide Fixed-combination Therapy

OralManufacturer states fixed-combination preparation should not be used for initial treatment of hypertension, except in severe hypertension when benefits of achieving prompt BP reduction are considered to outweigh risks of initiating combination therapy.2

If BP is not adequately controlled by monotherapy with losartan potassium or hydrochlorothiazide (25 mg daily), if BP is controlled but hypokalemia is problematic at this hydrochlorothiazide dosage, or in those with severe hypertension in whom the potential benefit of achieving prompt BP control outweighs the potential risk of initiating therapy with the commercially available fixed combination, can use the fixed-combination tablets once daily (losartan potassium 50 mg and hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg; then losartan potassium 100 mg and hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg, if BP remains uncontrolled after about 3 weeks of therapy [or after 2–4 weeks of therapy in those with severe hypertension]).2

If BP is not adequately controlled by monotherapy with losartan potassium 100 mg daily, can switch to fixed-combination tablets once daily (losartan potassium 100 mg and hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg; then losartan potassium 100 mg and hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg [administered as 2 tablets of the fixed combination containing 50 mg of losartan potassium and 12.5 mg of hydrochlorothiazide, or alternatively, as 1 tablet of the fixed combination containing 100 mg of losartan potassium and 25 mg of hydrochlorothiazide] if BP remains uncontrolled after about 3 weeks of therapy).2

Prevention of Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality

Oral

Initially, 50 mg once daily.1 Adjust dosage based on BP response.1 2 If indicated, add hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg daily and/or increase dosage of losartan to 100 mg once daily.1 2 Subsequently, may increase hydrochlorothiazide dosage to 25 mg once daily.1 2 Alternatively, administer fixed combination of losartan potassium and hydrochlorothiazide at appropriate dosages.2

Diabetic Nephropathy

Oral

Initially, 50 mg once daily.1 If BP is not adequately controlled, increase dosage to 100 mg once daily.1

Heart Failure† [off-label]

Oral

Initially, 25–50 mg once daily recommended by ACCF and AHA in patients with prior or current symptoms of heart failure and reduced LVEF† [off-label] (ACCF/AHA stage C heart failure).524

ACCF and AHA recommend maximum dosage of 50–150 mg once daily in patients with ACCF/AHA stage C heart failure.524

Reevaluate BP, renal function, and serum potassium concentrations within 1–2 weeks after initiation of therapy and monitor such parameters closely after dosage changes.524

Prescribing Limits

Pediatric Patients

Hypertension

Oral

Maximum 1.4 mg/kg or 100 mg daily.1 1150

Adults

Hypertension

Losartan/Hydrochlorothiazide Fixed-combination Therapy

OralMaximum 100 mg of losartan potassium and 25 mg of hydrochlorothiazide daily as the fixed combination.2

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

Manufacturer recommends initial dosage of 25 mg once daily in adults with a history of hepatic impairment.1

Use of losartan in fixed combination with hydrochlorothiazide is not recommended in patients with hepatic impairment.2

Renal Impairment

No initial dosage adjustments recommended by manufacturer for adults with renal impairment, including those undergoing hemodialysis.1 Use not recommended in pediatric patients with Clcr <30 mL/minute per 1.73 m2.1

Use of losartan in fixed combination with hydrochlorothiazide is not recommended in patients with severe renal impairment.2

Geriatric Patients

No initial dosage adjustments necessary.1

Volume- and/or Salt-depleted Patients

Correct volume and/or salt depletion prior to initiation of therapy or initiate therapy under close medical supervision using lower initial dosage (25 mg once daily).1 2

Use of losartan in fixed combination with hydrochlorothiazide is not recommended in patients with intravascular volume depletion (e.g., patients receiving diuretics).2

Cautions for Losartan

Contraindications

-

Known hypersensitivity to losartan or any ingredient in the formulation.1 2

-

Concomitant therapy with aliskiren in patients with diabetes mellitus.1 2 550 (See Specific Drugs under Interactions.)

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Fetal/Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality

Possible reduction in renal function and increase in fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality when drugs that act on the renin-angiotensin system (e.g., angiotensin II receptor antagonists, ACE inhibitors, aliskiren) are used during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy.1 2 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 57 (See Boxed Warning.) Resulting oligohydramnios can be associated with fetal lung hypoplasia and skeletal deformations.1 2 Potential neonatal effects include skull hypoplasia, anuria, hypotension, renal failure, and death.1 2

Discontinue losartan as soon as possible when pregnancy is detected, unless continued use is considered lifesaving.1 56 57 Nearly all women can be transferred successfully to alternative therapy for the remainder of their pregnancy.1 11 13

Sensitivity Reactions

Anaphylactoid reactions and/or angioedema possible;1 2 not recommended in patients with a history of angioedema associated with or unrelated to ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor antagonist therapy.58 544 545

Other Warnings and Precautions

Hypotension

Possible symptomatic hypotension, particularly in volume- and/or salt-depleted patients (e.g., those treated with diuretics).1 2 (See Volume- and/or Salt-Depleted Patients under Dosage and Administration.)

Malignancies

In July 2010, FDA initiated a safety review of angiotensin II receptor antagonists after a published meta-analysis found a modest but statistically significant increase in risk of new cancer occurrence in patients receiving an angiotensin II receptor antagonist compared with control.120 121 123 126 However, subsequent studies, including a larger meta-analysis conducted by FDA, have not shown such risk.126 127 128 129 Based on currently available data, FDA has concluded that angiotensin II receptor antagonists do not increase the risk of cancer.126

Renal Effects

Possible oliguria, progressive azotemia and, rarely, acute renal failure and/or death in patients with severe heart failure.1 2

Increases in BUN and Scr possible in patients with renal artery stenosis, CKD, or volume depletion.1 2

Consider withholding or discontinuing losartan in patients who develop a clinically important reduction in renal function while receiving losartan.1 2

Effects on Potassium

Hyperkalemia can develop, especially in patients with renal impairment or diabetes mellitus and those receiving agents that can increase serum potassium concentration (e.g., potassium-sparing diuretics, potassium supplements, potassium-containing salt substitutes).1 2

Use of Fixed Combinations

When losartan is used in fixed combination with hydrochlorothiazide, consider the cautions, precautions, and contraindications associated with hydrochlorothiazide.2

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Can cause fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.1 2 (See Boxed Warning.) Discontinue as soon as possible when pregnancy is detected.1 2 (See Fetal/Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality under Cautions.)

Lactation

Losartan and its active metabolite are distributed into milk in rats; not known whether distributed into human milk.1 2 Discontinue nursing or the drug.1 2

Pediatric Use

If oliguria or hypotension occurs in neonates with a history of in utero exposure to losartan, support BP and renal function; exchange transfusions or dialysis may be required.1 2 (See Fetal/Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality under Cautions.)

Safety and efficacy not established in children <6 years of age or in pediatric patients with Clcr <30 mL/minute per 1.73 m2.1

Geriatric Use

No substantial differences in safety or efficacy of losartan monotherapy relative to younger adults, but increased sensitivity cannot be ruled out.1

No apparent overall differences in efficacy with fixed combination containing losartan and hydrochlorothiazide in patients ≥65 years of age compared with younger adults.2 Adverse effects more frequent in geriatric patients compared with younger patients; select dosage with caution.2

Hepatic Impairment

Systemic exposure to losartan and its active metabolite may be increased.1 (See Absorption: Special Populations, under Pharmacokinetics.) Initial dosage adjustment recommended.1 (See Hepatic Impairment under Dosage and Administration.)

Use of losartan in fixed combination with hydrochlorothiazide is not recommended in patients with hepatic impairment (tablet dosage exceeds recommended initial dosage).2

Renal Impairment

Deterioration of renal function may occur.1 37 (See Renal Effects under Cautions.)

Use of losartan in fixed combination with hydrochlorothiazide is not recommended in patients with Clcr <30 mL/minute.2

Black Patients

BP reduction may be smaller in black patients than in patients of other races.1 2 (See Hypertension under Uses.)

No evidence that the benefits of therapy in reducing the risk of cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy apply to black patients.1

Common Adverse Effects

Patients with hypertension: upper respiratory infection,1 2 dizziness,1 2 nasal congestion, back pain, leg pain, muscle cramp, sinusitis.

Patients with diabetic nephropathy: Urinary tract infection, diarrhea, anemia, asthenia/fatigue, hypoglycemia, chest pain, cough, bronchitis, diabetic vascular disease, influenza-like disease, cataracts, cellulitis, hyperkalemia, hypotension, muscular weakness, sinusitis, gastritis, hypoesthesia, infection, knee pain, and leg pain.1

Drug Interactions

Formation of active metabolite appears to be mediated by CYP2C9.2 CYP3A4 apparently contributes to formation of inactive metabolites.2

Drugs Affecting Hepatic Microsomal Enzymes

CYP2C9 inhibitors: Possible inhibition of the formation of losartan’s active metabolite.1 2

CYP3A4 inhibitors: Clinically important interactions unlikely (possible increased concentration of losartan, but no effects on formation of active metabolite observed).2

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comment |

|---|---|---|

|

ACE inhibitors |

Increased risk of renal impairment, hyperkalemia, and hypotension1 2 |

Generally avoid concomitant use1 2 Monitor BP, renal function, and electrolytes if used concomitantly1 2 |

|

Aliskiren |

Increased risk of renal impairment, hyperkalemia, and hypotension1 2 550 |

Generally avoid concomitant use1 2 Monitor BP, renal function, and electrolytes if used concomitantly1 2 550 Concomitant use contraindicated in patients with diabetes mellitus1 2 550 Avoid concomitant use in patients with GFR <60 mL/minute1 2 550 |

|

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists |

Increased risk of renal impairment, hyperkalemia, and hypotension1 2 |

Generally avoid concomitant use1 2 Monitor BP, renal function, and electrolytes if used concomitantly1 2 |

|

Cimetidine |

||

|

Digoxin |

||

|

Diuretics, potassium-sparing |

||

|

Erythromycin |

Clinically important pharmacokinetic interaction unlikely2 |

|

|

Fluconazole |

Decreased plasma concentrations of losartan’s active metabolite and increased plasma losartan concentrations1 2 |

|

|

Hydrochlorothiazide |

Pharmacokinetic interaction unlikely1 2 Additive hypotensive effects; used for therapeutic advantage in hypertension treatment1 2 |

|

|

Ketoconazole |

Conversion of losartan to its active metabolite unaffected1 2 |

|

|

Lithium |

||

|

NSAIAs, including selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors |

Possible deterioration of renal function in geriatric, volume-depleted, or renally impaired patients1 2 |

Monitor renal function periodically1 |

|

Phenobarbital |

||

|

Rifampin |

Decreased plasma concentrations of losartan and its active metabolite1 2 |

|

|

Salt substitutes, potassium-containing |

||

|

Warfarin |

Losartan Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Well absorbed after oral administration but undergoes substantial first-pass metabolism.1 2

Systemic bioavailability of losartan is about 33%.1 2 Bioavailability of the suspension formulation (see Oral Administration under Dosage and Administration) is similar to that of losartan tablets with respect to both the drug and its active metabolite.1

Peak plasma concentrations of losartan and its active metabolite attained 1 and 3–4 hours, respectively, following oral administration.1

Onset

Antihypertensive effect evident within 1 week, with maximum BP reduction after 3–6 weeks.1

Food

Food slows absorption of losartan and decreases its peak plasma concentration but has minimal effect on AUC of losartan or its active metabolite.1 2

Special Populations

In pediatric patients, pharmacokinetics of losartan and its active metabolite generally are similar to historical data in adults.1

In patients with hepatic impairment, oral bioavailability is about 2 times higher than in those with normal hepatic function.1

In patients with mild to moderate alcoholic cirrhosis, plasma concentration of losartan and its active metabolite were about 5 and 2 times those of healthy individuals, respectively.1 2

In patients with mild (Clcr 50–74 mL/minute) or moderate (Clcr 30–49 mL/minute) renal impairment, plasma concentrations and AUC of losartan and its active metabolite are increased by 50–90%.2

Distribution

Extent

Crosses the placenta and is distributed in the fetus in animals.1 2

Crosses the blood-brain barrier poorly, if at all, in animals.1 2

Distributed into milk in rats; not known whether distributed into human milk.1 2

Plasma Protein Binding

Losartan and its active metabolite: >98%.1 2

Elimination

Metabolism

Undergoes biotransformation through CYP2C9 to an active carboxylic acid metabolite that is responsible for most of the drug’s angiotensin II receptor antagonism.2 CYP3A4 apparently contributes to formation of inactive metabolites.2

Elimination Route

Eliminated mainly in urine and feces (via bile).1 2

Half-life

Terminal half-life of losartan and its active metabolite is approximately 2 and 6–9 hours, respectively.1 2

Special Populations

In patients with mild to moderate alcoholic cirrhosis, total plasma clearance of losartan is about 50% lower than in those with normal hepatic function.1

In patients with mild or moderate renal impairment, renal clearance of losartan and its active metabolite is decreased by 55–85%.2 Neither losartan nor its active metabolite is removed by hemodialysis.1 2

Stability

Storage

Oral

Extemporaneous Suspension

2.5-mg/mL preparation of losartan potassium tablets in a mixture of syrup (Ora-Sweet) and suspending vehicle (Ora-Plus) (see Oral Administration under Dosage and Administration): Up to 30 days at 2–8°C.1

Tablets

Tight container at 25°C (may be exposed to 15–30°C).1 2 Protect from light.1 2

Actions

-

Losartan (prodrug) has little pharmacologic activity until activated in the liver.1 2

-

Losartan’s active metabolite is 10 to 40 times more potent by weight than losartan and appears to be a reversible, noncompetitive inhibitor of the AT1 receptor.1 2

-

Blocks the physiologic actions of angiotensin II, including vasoconstrictor and aldosterone-secreting effects.1 2

Advice to Patients

-

Importance of women informing their clinician if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1 2

-

Importance of advising patients not to use potassium supplements or salt substitutes containing potassium without consulting their clinician.1

-

Importance of informing clinicians of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs (including salt substitutes containing potassium).1 2

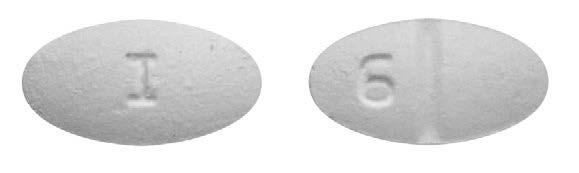

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Tablets, film-coated |

25 mg |

Cozaar |

Merck |

|

50 mg |

Cozaar |

Merck |

||

|

100 mg |

Cozaar |

Merck |

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Tablets, film-coated |

50 mg with Hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg |

Hyzaar |

Merck |

|

100 mg with Hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg |

Hyzaar |

Merck |

||

|

100 mg with Hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg |

Hyzaar |

Merck |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2024, Selected Revisions November 5, 2018. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

1. Merck & Co., Inc. Cozaar (losartan potassium) tablets prescribing information. Whitehouse Station, NJ; 2015 Dec.

2. Merck & Co, Inc. Hyzaar (losartan potassium-hydrochlorothiazide) tablets prescribing information. Whitehouse Station, NJ; 2015 Dec.

4. Anon. Drugs for hypertension. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1993; 35:55-60. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8099706?dopt=AbstractPlus

6. Rey E, LeLorier J, Burgess E et al. Report of the Canadian Hypertension Society consensus conference: 3. pharmacologic treatment of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. CMAJ. 1997; 157:1245-54. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1228354&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9361646?dopt=AbstractPlus

7. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG technical bulletin No. 219: hypertension in pregnancy. 1996 Jan.

8. Hanssens M, Keirse MJ, Van Assche FA. Fetal and neonatal effects of treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1991; 78:128-35. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2047053?dopt=AbstractPlus

9. Brent RL, Beckman D. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, an embryopathic class of drugs with unique properties: information for clinical teratology counselors. Teratology. 1991; 43:543-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1882342?dopt=AbstractPlus

10. Piper JM, Ray WA, Rosa FW. Pregnancy outcome following exposure to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Obstet Gynecol. 1992; 80:429-32. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1495700?dopt=AbstractPlus

11. Sibai BM. Treatment of hypertension in pregnant women. N Engl J Med. 1996; 335:257-65. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8657243?dopt=AbstractPlus

12. Barr M, Cohen MM. ACE inhibitor fetopathy and hypocalvaria: the kidney-skull connection. Teratology. 1991; 44:485-95. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1771591?dopt=AbstractPlus

13. US Food and Drug Administration. Dangers of ACE inhibitors during second and third trimesters of pregnancy. FDA Med Bull. 1992; 22:2.

14. Schubiger G, Flury G, Nussberger J. Enalapril for pregnancy-induced hypertension: acute renal failure in a neonate. Ann Intern Med. 1988; 108:215-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2829674?dopt=AbstractPlus

15. Anon. ACE-inhibitors: contraindicated in pregnancy. WHO Drug Information. 1990; 4:23.

16. Joint letter of Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Ciba-Geigy Corporation, Pharmaceutical Division; Hoechst-Roussel Pharmaceuticals Inc; Merck Human Health Division; Parke-Davis, Division of Warner-Lambert Company. Important warning information regarding use of ACE inhibitors in pregnancy. 1992 Mar 16.

17. Anon. Consensus recommendations for the management of chronic heart failure. On behalf of the membership of the advisory council to improve outcomes nationwide in heart failure. Part II. Management of heart failure: approaches to the prevention of heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1999; 83:9-38A.

18. Izzo JL, Levy D, Black HR. Importance of systolic blood pressure in older Americans. Hypertension. 2000; 35:1021-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10818056?dopt=AbstractPlus

19. Frohlich ED. Recognition of systolic hypertension for hypertension. Hypertension. 2000; 35:1019-20. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10818055?dopt=AbstractPlus

20. Merck & Co, Inc. Results of second heart-failure study with Cozaar presented at American Heart Association scientific sessions. West Point, PA; 1999 Nov 10. Press release from web site. http://www.merck.com

21. Bakris GL, Williams M, Dworkin L et al. Preserving renal function in adults with hypertension and diabetes: a consensus approach. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000; 36:646-61. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10977801?dopt=AbstractPlus

23. Pitt B, Segal R, Martinez FA et al. Randomised trial of losartan versus captopril in patients over 65 with heart failure (Evaluation of Losartan in the Elderly Study, ELITE). Lancet. 1997; 349:747-52. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9074572?dopt=AbstractPlus

24. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet. 1998; 351:1755-62. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9635947?dopt=AbstractPlus

26. Paster RZ, Snavely DB, Sweet AR et al. Use of losartan in the treatment of hypertensive patients with a history of cough induced by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Clin Ther. 1998; 20:978-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9829449?dopt=AbstractPlus

27. Hunt SA, Baker DW, Chin MH et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic heart failure in the adult. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1995 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). 2001. Available from ACC website. Accessed July 25, 2002. http://www.cardiosource.org/Science-And-Quality/Practice-Guidelines-and-Quality-Standards.aspx

31. Cohn JN, Tognoni G, for the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial Investigators. A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:1667-75. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11759645?dopt=AbstractPlus

32. Novartis. Diovan (valsartan) tablets prescribing information. East Hanover, NJ; 2002 Aug.

33. Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:861-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11565518?dopt=AbstractPlus

34. Williams MA, Fleg JL, Ades PA et al. Secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in the elderly (with emphasis on patients ≥ 75 years of age). An American Heart Association Scientific Statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology Subcommittee on Exercise, Cardiac rehabilitation, and Prevention. Circulation. 2002; 105:1735-43. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11940556?dopt=AbstractPlus

35. Williams CL, Hayman LL, Daniels SR et al. Cardiovascular health in childhood: a statement for health professional from the Committee on Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young (AHOY) of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002; 106:143-60. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12093785?dopt=AbstractPlus

36. Parving HH, Lehnert H, Bröchner-Mortensen J et al. The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:870-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11565519?dopt=AbstractPlus

37. Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:851-60. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11565517?dopt=AbstractPlus

38. Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP et al. The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 1993; 329:1456-62. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8413456?dopt=AbstractPlus

39. Remuzzi G. Slowing the progression of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 1993; 329:1496-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8413463?dopt=AbstractPlus

41. Kaplan NM. Choice of initial therapy for hypertension. JAMA. 1996; 275:1577-80. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8622249?dopt=AbstractPlus

42. Viberti G, Mogensen CE, Groop LC et al. Effect of captopril on progression to clinical proteinuria in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and microalbuminuria. JAMA. 1994; 271:275-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8295285?dopt=AbstractPlus

43. Fournier A. The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 1994; 330:937. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8114873?dopt=AbstractPlus

44. Kasiske VL, Kalil RSN, Ma JZ et al. Effect of antihypertensive therapy on the kidney in patients with diabetes: a meta-regression analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1993; 118:129-138. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8416309?dopt=AbstractPlus

45. Björck S, Mulec H, Johnsen SA et al. Renal protective effect of enalapril in diabetic nephropathy. BMJ. 1992; 304:339-43. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1540729?dopt=AbstractPlus

46. Cook J, Daneman D, Spino M et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor therapy to decrease microalbuminuria in normotensive children with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr. 1990; 117:39-45. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2196359?dopt=AbstractPlus

47. Appel LJ. The verdict from ALLHAT—thiazide diuretics are the preferred initial therapy for hypertension. JAMA. 2002; 288:3039-60. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12479770?dopt=AbstractPlus

48. The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002; 288:2981-97. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12479763?dopt=AbstractPlus

53. Dahlöf B, Dewvereux RB, Kjeldsen SE et al and the Life study group. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention for Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002; 359:995-1003.

54. Fossum E, Moan A, Kjeldsen SE et al and the Life study group. The effect of losartan versus atenolol on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with hypertension taking aspirin: The Losartan Intervention for Endpoint reduction in hypertension (LIFE) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46:770-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16139123?dopt=AbstractPlus

55. AstraZeneca. Atacand (candesartan cilexetil) tablets prescribing information. Wilmington, DE; 2005 May.

56. Cooper WO, Hernandez-Diaz S, Arbogast PG et al. Major congenital malformations after first-trimester exposure to ACE inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354:2443-51. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16760444?dopt=AbstractPlus

57. Food and Drug Administration. FDA public health advisory: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE inhibitor) drugs and pregnancy. From FDA website. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm053113.htm

58. Howes LG, Tran D. Can angiotensin receptor antagonists be used safely in patients with previous ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema? Drug Saf. 2002; 25:73-6.

59. Dahlof B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the losartan intervention for endpoint reduction in the hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002; 359:995-1003. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11937178?dopt=AbstractPlus

120. Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: ongoing safety review of the angiotensin receptor blockers and cancer. Rockville, MD; 2010 Jul 15. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm218845.htm

121. Sipahi I, Debanne SM, Rowland DY et al. Angiotensin-receptor blockade and risk of cancer: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol. 2010; 11:627-36. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20542468?dopt=AbstractPlus

122. Nissen SE. Angiotensin-receptor blockers and cancer: urgent regulatory review needed. Lancet Oncol. 2010; 11:605-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20542469?dopt=AbstractPlus

123. Sica DA. Angiotensin receptor blockers and the risk of malignancy: a note of caution. Drug Saf. 2010; 33:709-12. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20701404?dopt=AbstractPlus

126. Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: No increase in risk of cancer with certain blood pressure drugs-angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). Rockville, MD; 2011 Jun 2. Available from FDA website. Accessed 2011 Jun 15. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm257516.htm

127. Bangalore S, Kumar S, Kjeldsen SE et al. Antihypertensive drugs and risk of cancer: network meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of 324,168 participants from randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2011; 12:65-82. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21123111?dopt=AbstractPlus

128. ARB Trialists Collaboration. Effects of telmisartan, irbesartan, valsartan, candesartan, and losartan on cancers in 15 trials enrolling 138,769 individuals. J Hypertens. 2011; 29:623-35. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21358417?dopt=AbstractPlus

129. Pasternak B, Svanström H, Callréus T et al. Use of angiotensin receptor blockers and the risk of cancer. Circulation. 2011; 123:1729-36. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21482967?dopt=AbstractPlus

130. Volpe M, Morganti A. 2010 Position Paper of the Italian Society of Hypertension (SIIA): Angiotensin Receptor Blockers and Risk of Cancer. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2011; 18:37-40. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21612311?dopt=AbstractPlus

131. Siragy HM. A current evaluation of the safety of angiotensin receptor blockers and direct renin inhibitors. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2011; 7:297-313. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3104607&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21633727?dopt=AbstractPlus

132. Granger CB, McMurray JJ, Yusuf S et al. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Alternative trial. Lancet. 2003; 362:772-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13678870?dopt=AbstractPlus

501. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014; 311:507-20. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24352797?dopt=AbstractPlus

502. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2013; 31:1281-357. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23817082?dopt=AbstractPlus

503. Go AS, Bauman MA, Coleman King SM et al. An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hypertension. 2014; 63:878-85. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24243703?dopt=AbstractPlus

504. Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014; 16:14-26. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24341872?dopt=AbstractPlus

505. Wright JT, Fine LJ, Lackland DT et al. Evidence supporting a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 150 mm Hg in patients aged 60 years or older: the minority view. Ann Intern Med. 2014; 160:499-503. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24424788?dopt=AbstractPlus

506. Mitka M. Groups spar over new hypertension guidelines. JAMA. 2014; 311:663-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24549531?dopt=AbstractPlus

507. Peterson ED, Gaziano JM, Greenland P. Recommendations for treating hypertension: what are the right goals and purposes?. JAMA. 2014; 311:474-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24352710?dopt=AbstractPlus

508. Bauchner H, Fontanarosa PB, Golub RM. Updated guidelines for management of high blood pressure: recommendations, review, and responsibility. JAMA. 2014; 311:477-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24352759?dopt=AbstractPlus

511. JATOS Study Group. Principal results of the Japanese trial to assess optimal systolic blood pressure in elderly hypertensive patients (JATOS). Hypertens Res. 2008; 31:2115-27. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19139601?dopt=AbstractPlus

515. Thomas G, Shishehbor M, Brill D et al. New hypertension guidelines: one size fits most?. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014; 81:178-88. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24591473?dopt=AbstractPlus

523. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2012; 126:e354-471. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23166211?dopt=AbstractPlus

524. WRITING COMMITTEE MEMBERS, Yancy CW, Jessup M et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013; 128:e240-327. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23741058?dopt=AbstractPlus

525. Smith SC, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO et al. AHA/ACCF Secondary Prevention and Risk Reduction Therapy for Patients with Coronary and other Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2011; 124:2458-73. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22052934?dopt=AbstractPlus

526. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR et al. Guidelines for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014; :. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24788967?dopt=AbstractPlus

527. O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013; 127:e362-425. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23247304?dopt=AbstractPlus

528. Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB et al. Effects of candesartan on mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: the CHARM-Overall programme. Lancet. 2003; 362:759-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13678868?dopt=AbstractPlus

530. Myers MG, Tobe SW. A Canadian perspective on the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) hypertension guidelines. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014; 16:246-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24641124?dopt=AbstractPlus

534. Qaseem A, Hopkins RH, Sweet DE et al. Screening, monitoring, and treatment of stage 1 to 3 chronic kidney disease: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2013; 159:835-47. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24145991?dopt=AbstractPlus

535. Taler SJ, Agarwal R, Bakris GL et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for management of blood pressure in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013; 62:201-13. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23684145?dopt=AbstractPlus

536. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Blood Pressure Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the management of blood pressure in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012: 2: 337-414.

541. Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H et al. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur Heart J. 2012; 33:1635-701. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22555213?dopt=AbstractPlus

543. National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative. K/DOQI Clinical practice guidelines on hypertension and antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease (2002). From National Kidney Foundation website. http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_commentaries.cfm

544. Kirk JK. Therapy with angiotensin II receptor antagonists. Clin Geriatrics. From the MultiMedia Health Care website:. http://www.mmhc.com/cg/articles/CG0004/kirk.html

545. Papademetriou V, Reif M, Henry D et al. Combination therapy with candesartan cilexetil and hydrochlorothiazide in patients with systemic hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2000; 2:372-8.

550. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: new warning and contraindication for blood pressure medicines containing aliskiren (Tekturna). Rockville, MD; 2012 April 4. From FDA website. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm300889.htm

701. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016; :. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27206819?dopt=AbstractPlus

702. McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014; 371:993-1004. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25176015?dopt=AbstractPlus

703. Ansara AJ, Kolanczyk DM, Koehler JM. Neprilysin inhibition with sacubitril/valsartan in the treatment of heart failure: mortality bang for your buck. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016; 41:119-27. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26992459?dopt=AbstractPlus

800. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B et al. 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update on New Pharmacological Therapy for Heart Failure: An Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2016; :. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27208050?dopt=AbstractPlus

1150. Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM et al. Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017; 140 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28827377?dopt=AbstractPlus

1200. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018; 71:el13-e115. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29133356?dopt=AbstractPlus

1201. Bakris G, Sorrentino M. Redefining hypertension - assessing the new blood-pressure guidelines. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:497-499. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29341841?dopt=AbstractPlus

1202. Carey RM, Whelton PK, 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guideline Writing Committee. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: synopsis of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association hypertension guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018; 168:351-358. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29357392?dopt=AbstractPlus

1207. Burnier M, Oparil S, Narkiewicz K et al. New 2017 American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology guideline for hypertension in the adults: major paradigm shifts, but will they help to fight against the hypertension disease burden?. Blood Press. 2018; 27:62-65. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29447001?dopt=AbstractPlus

1209. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R et al. Pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in adults aged 60 years or older to higher versus lower blood pressure targets: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017; 166:430-437. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28135725?dopt=AbstractPlus

1210. SPRINT Research Group, Wright JT, Williamson JD et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:2103-16. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26551272?dopt=AbstractPlus

1213. Reboussin DM, Allen NB, Griswold ME et al. Systematic review for the 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 71:2176-2198. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29146534?dopt=AbstractPlus

1214. American Diabetes Association. 9. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes 2018. Diabetes Care. 2018; 41:S86-S104. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29222380?dopt=AbstractPlus

1215. de Boer IH, Bangalore S, Benetos A et al. Diabetes and hypertension: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017; 40:1273-1284. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28830958?dopt=AbstractPlus

1216. Taler SJ. Initial treatment of hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:636-644. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29443671?dopt=AbstractPlus

1218. Messerli FH, Bangalore S, Bavishi C et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in hypertension: to use or not to use?. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 71:1474-1482. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29598869?dopt=AbstractPlus

1219. Karmali KN, Lloyd-Jones DM. Global risk assessment to guide blood pressure management in cardiovascular disease prevention. Hypertension. 2017; 69:e2-e9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28115516?dopt=AbstractPlus

1220. Cifu AS, Davis AM. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults. JAMA. 2017; 318:2132-2134. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29159416?dopt=AbstractPlus

1222. Bell KJL, Doust J, Glasziou P. Incremental benefits and harms of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association high blood pressure guideline. JAMA Intern Med. 2018; 178:755-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29710197?dopt=AbstractPlus

1223. LeFevre M. ACC/AHA hypertension guideline: What is new? What do we do?. Am Fam Physician. 2018; 97(6):372-3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29671534?dopt=AbstractPlus

1224. Brett AS. New hypertension guideline is released. From NEJM Journal Watch website. Accessed 2018 Jun 18. https://www.jwatch.org/na45778/2017/12/28/nejm-journal-watch-general-medicine-year-review-2017

1229. Ioannidis JPA. Diagnosis and treatment of hypertension in the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines and in the real world. JAMA. 2018; 319(2):115-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29242891?dopt=AbstractPlus

1232. American Diabetes Association. 10. Microvascular complications and foot care: standards of medical care in diabetes 2018. Diabetes Care. 2018; 41:S105-S118. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29222381?dopt=AbstractPlus

1233. Remuzzi G, Macia M, Ruggeneti P. Prevention and treatment of diabetic renal disease in type 2 diabetes: the BENEDICT study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006; 17(4 Suppl 2 ):S90-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16565256?dopt=AbstractPlus

1234. Haller H, Ito S, Izzo JL Jr. et al. Olmesartan for the delay or prevention of microalbuminuria in type 2 diabetes. N Eng J Med. 2011; 364:907-17. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21388309?dopt=AbstractPlus

Frequently asked questions

- Can you eat bananas when taking losartan?

- Does Losartan block the receptor used by the Coronavirus?

- Losartan vs Valsartan - What's the difference between them?

- Does losartan cause rapid heart rate, irregular heartbeat or low blood pressure?

- Are losartan and losartan potassium the same or different drugs?

More about losartan

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (563)

- Drug images

- Latest FDA alerts (17)

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- Patient tips

- During pregnancy

- Support group

- Drug class: angiotensin receptor blockers

- Breastfeeding

- En español