Diupres-500 Side Effects

Generic name: chlorothiazide / reserpine

Note: This document contains side effect information about chlorothiazide / reserpine. Some dosage forms listed on this page may not apply to the brand name Diupres-500.

Applies to chlorothiazide/reserpine: oral tablet.

Warning

Stand up slowly from a sitting or lying position. Chlorothiazide and reserpine may make you feel dizzy.

Do not stop taking chlorothiazide and reserpine suddenly. Even if you feel better, you need this medication to control your condition. Stopping suddenly could cause severe high blood pressure, anxiety, and other dangerous side effects.

Tell your doctor and dentist that you are taking this medication before having surgery.

If you experience any of the following serious side effects, stop taking chlorothiazide and reserpine and seek emergency medical attention:

-

an allergic reaction (difficulty breathing, closing of your throat, swelling of your lips, tongue or face, hives);

-

a very irregular heartbeat;

-

heart failure (shortness of breath, swelling of ankles or legs, sudden weight gain of 5 pounds or more);

-

unusual fatigue;

-

abnormal bleeding or bruising;

-

yellow skin or eyes;

-

confusion;

-

fainting;

-

uncontrollable hand, arm, or leg movements;

-

chest pain; or

-

little or no urine.

Other, less serious side effects are more likely to occur. Continue to take chlorothiazide and reserpine and talk to your doctor if you experience

-

fatigue or drowsiness;

-

dizziness (avoid standing up too quickly and use caution when performing hazardous activities);

-

anxiety, depression, or nightmares;

-

diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, or an acid stomach (take chlorothiazide and reserpine with food or milk if it upsets your stomach);

-

abdominal pain;

-

stuffy nose or a dry mouth (sucking on ice chips or sugarless hard candy may relieve a dry mouth);

-

blurred vision;

-

headache;

-

tingling or numbness in your arms, legs, hands, or feet;

-

excessive urination;

-

muscle weakness or cramps;

-

increased hunger or thirst;

-

weight gain;

-

sensitivity to sunlight; or

-

impotence or difficulty ejaculating.

Side effects other than those listed here may also occur. Talk to your doctor about any side effect that seems unusual or that is especially bothersome.

For Healthcare Professionals

Applies to chlorothiazide / reserpine: oral tablet.

Respiratory

Rare reports of reserpine-induced bronchospasm are believed to be due to inactivation of beta-adrenergic receptors, which can result in a marked potentiation of the bronchoconstrictive effect of histamine.[Ref]

Respiratory side effects related to reserpine have been reported. Nasal congestion has been reported in 8% of patients. Rare cases of bronchospasm have also been associated with reserpine.[Ref]

Psychiatric

The depressive syndrome usually consists of melancholy, loss of self confidence, early morning awakening, loss of libido, and reduced appetite.

A case of reserpine withdrawal psychosis has been reported. This uncommon condition may be due to dopamine receptor supersensitivity, which develops during reserpine therapy.[Ref]

Psychiatric problems related to reserpine therapy can be serious. Depression occurs in 2% to 28% of patients, is more likely when daily doses exceed 0.5 mg, and can present at any time during therapy. Suicidal ideation has been reported. Reserpine-induced depression is quickly reversible if therapy is withdrawn as soon as the syndrome is recognized, but can persist for several months after drug discontinuation if the syndrome fully develops. Reserpine withdrawal psychosis has been reported.[Ref]

Metabolic

Hyperuricemia may be an important consideration in patients with a history of gout. Hypophosphatemia and low serum magnesium concentrations may occur, but are usually clinically insignificant except in malnourished patients.

Rare cases of hypercalcemia, milk-alkali syndrome (hypercalcemia, metabolic alkalosis, and renal insufficiency) have been associated with chlorothiazide.

Chlorothiazide-induced hypercalcemia appears to depend on circulating parathyroid hormone.[Ref]

Metabolic changes associated with chlorothiazide, as with other thiazide diuretics, are relatively common, especially when daily doses greater than 500 mg are used. Mild hypokalemia (decrease of 0.5 mEq/L) occurs in up to 50%, and may predispose patients to cardiac arrhythmias. Metabolic alkalosis, hyponatremia, hypomagnesemia, hypophosphatemia, hypercalcemia, hyperglycemia, hypercholesterolemia and hyperuricemia are also relatively common. The electrolyte and intravascular fluid shifts that may occur during chlorothiazide diuresis can provoke hepatic encephalopathy in patients with hepatic cirrhosis.[Ref]

Nervous system

Nervous system side effects include sedation, lethargy (different from the psychiatric syndrome of depression), drowsiness, weakness, vertigo, insomnia, or headache in approximately 1% to 5% of patients who are taking reserpine. While reserpine is used to treat tardive dyskinesia, extrapyramidal movements may worsen upon withdrawal of therapy. A case of CNS hypertension, believed to be due to cerebral edema, has been associated with reserpine, and rare cases of cerebrovascular insufficiency have been associated with some thiazide diuretics.[Ref]

Increased parkinsonian movements upon reserpine withdrawal (as with neuroleptics) may be due to supersensitivity to dopamine as a result of increased dopamine receptors that developed during reserpine therapy.[Ref]

Cardiovascular

Cardiovascular side effects include hypotension in 8% and bradycardia (and rare cases of syncope with bradycardia) in 3% of patients treated with reserpine. Hypotension may be more likely due to the added risk of chlorothiazide-induced intravascular volume depletion. A rare case of paroxysmal atrial tachycardia with block associated with reserpine in a patient who was not taking a digitalis preparation has been reported.[Ref]

A woman with paroxysmal atrial tachycardia developed sinus pauses during reserpine therapy which were reproducible by carotid massage, except when isoproterenol was given. Reserpine is known to increase vagal tone and to deplete cardiac catecholamines.

One patient, in a series of 231, had emergent hypertension, stroke, and thyrotoxic crisis. Reserpine 1 mg intramuscularly resulted in a blood pressure drop from 180/100 to an unmeasurable level. The patient recovered after isoproterenol therapy.[Ref]

Hypersensitivity

Thiazides may induce allergic reactions in patients who are allergic to sulfonamides.[Ref]

Hypersensitivity reactions to chlorothiazide usually involve the skin (cutaneous vasculitis, urticaria, rash, purpura), but may involve the gastrointestinal system (nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea), the genitourinary system (interstitial nephritis), and the respiratory system (acute noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, pneumonitis). Thiazide diuretics may induce phototoxic dermatitis.[Ref]

Gastrointestinal

Gastrointestinal side effects due to unopposed parasympathetic activity produced by catecholamine depletion may lead to increased gastrointestinal motility and secretory activity. Because of this, new diarrhea or worsening of existing diarrhea or increased salivation have been reported in 2% of patients. Diarrhea, vomiting, constipation, or abdominal pain occur in approximately 5% of patients who are taking chlorothiazide. Thiazide diuretics have been associated with acute cholecystitis and rare cases of pancreatitis.[Ref]

According to a retrospective case-controlled drug surveillance study, the relative risk of acute cholecystitis associated with the use of a thiazide diuretic is 2.0. The suspected explanation for this association is the potentially deleterious effect thiazides have on the serum lipid profile. Chlorothiazide-induced hypercholesterolemia or hypertriglyceridemia may enhance the formation of some types of gallstones.[Ref]

Dermatologic

Dermatologic reactions may indicate hypersensitivity to chlorothiazide. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, exfoliative dermatitis (including toxic epidermal necrolysis), and alopecia have been associated with thiazides in rare cases.[Ref]

Genitourinary

Genitourinary complaints are limited to impotence in approximately 5% of male patients.[Ref]

Endocrine

Endocrinologic abnormalities due to reserpine-induced hyperprolactinemia include gynecomastia in men and pseudolactation and breast engorgement in women. Changes associated with chlorothiazide, as with other thiazide diuretic agents, include decreased glucose tolerance and a potentially deleterious effect on the lipid profile. This may be important in some patients with or who are at risk for diabetes or coronary artery disease.[Ref]

Renal

Renal side effects including new or worsened renal insufficiency is probably a sign of intravascular volume depletion, and serves as a signal to reduce or withhold therapy. Rare cases of allergic interstitial nephritis have been associated with chlorothiazide.[Ref]

Hematologic

Hematologic side effects are rare. Rare cases of immune-complex hemolytic anemia, aplastic anemia, and thrombocytopenia have been associated with thiazide diuretics.[Ref]

Immunologic

Immunologic side effects are rare. A single case of angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy has been associated with reserpine. In a study of 231 patients, only 1 case of a lupus-like syndrome was observed (the patient had previously received hydralazine).[Ref]

A 79-year-old woman with hypertension, taking reserpine, potassium, hydrochlorothiazide, and ibuprofen, developed fatigue, anorexia, fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Associated laboratory findings showed anemia, lymphocytosis, thrombocytopenia, IgA kappa paraproteinemia, positive ANA, and a positive Coombs' test. Bone marrow biopsy, lymphangiography, and lymph node biopsy showed bone marrow lymphocytosis, enlarged foamy abdominal lymph nodes with irregular filling, and angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy. Within four days after discontinuation of reserpine (her other medications were continued), the paraprotein level normalized and the platelet count rose. After an additional nine months of prednisone therapy, all of her signs and symptoms resolved.[Ref]

Musculoskeletal

Musculoskeletal cramping or spasms have occasionally been reported during chlorothiazide diuresis.[Ref]

Oncologic

Oncology concerns were raised after a large drug surveillance center in Boston reported an association between reserpine, a stimulator of prolactin, and breast cancer in 1974. These findings were partially, but not completely, confirmed in two similar centers in Europe. A critical review of these studies elucidated several design flaws. Subsequent, controlled studies have failed to show an association between reserpine and an increased incidence of breast carcinoma.[Ref]

More about Diupres-500 (chlorothiazide / reserpine)

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

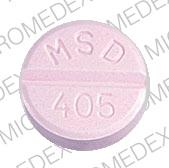

- Drug images

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: antiadrenergic agents (peripheral) with thiazides

Related treatment guides

References

1. Freis ED. Reserpine in hypertension: present status. Am Fam Physician. 1975;11:120-2.

2. Luxenberg J, Feigenbaum LZ. The use of reserpine for elderly hypertensive patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;31:556-9.

3. Applegate WB, Carper ER, Kahn SE, Westbrook L, Linton M, Baker MG, Runyan JW, Jr. Comparison of the use of reserpine versus alpha-methyldopa for second step treatment of hypertension in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1985;33:109-15.

4. Gibb WE, Malpas JS, Turner P, White RJ. Comparison of bethanidine, alpha-methyldopa, and reserpine in essential hypertension. Lancet. 1970;2:275-7.

5. Segal MS. Bronchospasm after reserpine. N Engl J Med. 1969;281:1426-7.

6. Atuk NO, Owen JA, Jr. Bronchospasm after reserpine. N Engl J Med. 1969;281:908-9.

7. Diamond L. Drug-induced bronchospasm. J Clin Pharmacol J New Drugs. 1970;10:215-6.

8. Kirschenbaum HL, Rosenberg JM. What to look out for with guanethidine and reserpine. RN. 1984;47:31-3.

9. Pfeifer HJ, Greenblatt DK, Koch-Wester J. Clinical toxicity of reserpine in hospitalized patients: a report from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program. Am J Med Sci. 1976;271:269-76.

10. Fleishman M. Letter: Reserpine, ECT, and depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1975;132:1088.

11. Lewis WH. Iatrogenic psychotic depressive reaction in hypertensive patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;127:1416-7.

12. Sharon E, Paolino JS, Kaplan D. Hematemesis after reserpine for Raynaud's phenomenon. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:479-80.

13. Blumenthal M, Davis R, Doe RP. Carcinoid syndrome following reserpine therapy in thyrotoxicosis. Arch Intern Med. 1965;116:819-23.

14. Widmer RB. Reserpine: the maligned antihypertensive drug. J Fam Pract. 1985;20:81-3.

15. Kent TA, Wilber RD. Reserpine withdrawal psychosis: the possible role of denervation supersensitivity of receptors. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1982;170:502-4.

16. Samuels AH, Taylor AJ. Reserpine withdrawal psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1989;23:129-30.

17. Berlant JL. Neuroleptics and reserpine in refractory psychoses. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1986;6:180-4.

18. Ambrosino SV. Depressive reactions associated with reserpine. N Y State J Med. 1974;74:860-4.

19. Reus VI. Behavioral side effects of medical drugs. Prim Care. 1979;6:283-94.

20. Goodwin FK, Bunney WE, Jr. Depressions following reserpine: a reevaluation. Semin Psychiatry. 1971;3:435-48.

21. Lindy S, Tarssanen L. Serum calcium and phosphorus in patients treated with thiazides and furosemide. Acta Med Scand. 1973;194:319-22.

22. Aneckstein AG, Weingold AB. Chlorothiazide-induced hepatic coma in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1966;95:136-7.

23. Gammon GD, Docherty JP. Thiazide-induced hypercalcemia in a manic-depressive patient. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137:1453-5.

24. Leigh H. Letter: Factitious hypokalemia. Ann Intern Med. 1974;80:111-2.

25. Parfitt AM. Thiazide-induced hypercalcemia in vitamin D-treated hypoparathyroidism. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:557-63.

26. Jackson WP, Nellen M. Effect of frusemide on carbohydrate metabolism, blood-pressure, and other modalities. A comparison with chlorothiazide. Br Med J. 1966;2:333-6.

27. Lapidus PW, Guidotti FP. Gout in orthopaedic practice: review of 232 cases. Clin Orthop. 1963;28:97-110.

28. Popovtzer MM, Subryan VL, Alfrey AC, Reeve EB, Schrier RW. The acute effect of chlorothiazide on serum-ionized calcium. Evidence for a parathyroid hormone-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 1975;55:1295-302.

29. Paloyan E, Farland M, Pickleman JR. Hyperparathyroidism coexisting with hypertension and prolonged thiazide administration. JAMA. 1969;210:1243-5.

30. Parfitt AM. Chlorothiazide-induced hypercalcemia in juvenile osteoporosis and hyperparathyroidism. N Engl J Med. 1969;281:55-9.

31. Moore TD, Bechtel TP. Hyponatremia secondary to tolbutamide and chlorothiazide. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1979;36:1107-10.

32. Gora ML, Seth SK, Bay WH, Visconti JA. Milk-alkali syndrome associated with use of chlorothiazide and calcium carbonate. Clin Pharm. 1989;8:227-9.

33. Sherlock S, Walker JG, Senewiratne B, Scott A. The complications of diuretic therapy in patients with cirrhosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1966;139:497-505.

34. Product Information. Diupres-250 (chlorothiazide-reserpine). Merck & Co., Inc.

35. Miller NR, Moses H. Transient oculomotor nerve palsy. Association with thiazide-induced glucose intolerance. JAMA. 1978;240:1887-8.

36. Bullock JD. Antihypertensive drugs and danger to vision . JAMA. 1977;237:2186.

37. Stern RS. When a uniquely effective drug is teratogenic. The case of isotretinoin. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1007-9.

38. Bacher NM, Lewis HA. Reserpine and tardive dyskinesia. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:719.

39. Dilsaver SC, Greden JF. Possible cholinergic mechanism in reserpine and tardive dyskinesia. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:151-2.

40. Peters HA. Questioning reserpine's adverse effect on tardive dyskinesia. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:1106.

41. Donatelli A, Geisen L, Feuer E. Case report of adverse effect of reserpine on tardive dyskinesia. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:239-40.

42. Murayama M, Yasuda K, Minamori Y, Mercado-Asis LB, Yamakita N, Miura K. Long term follow-up of Cushing's disease treated with reserpine and pituitary irradiation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:935-42.

43. Ross RT. Drug-induced parkinsonism and other movement disorders. Can J Neurol Sci. 1990;17:155-62.

44. Combs RM. Unusual response to reserpine in paroxysmal atrial tachycardia with block unassociated with digitalis. South Med J. 1967;60:839-42.

45. Stern RS, Kleinerman RA, Parrish JA, et al. Phototoxic reactions to photoactive drugs in patients treated with PUVA. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:1269-71.

46. Bowden FJ. Non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema after ingestion of chlorothiazide. BMJ. 1989;298:605.

47. Lyons H, Pinn VW, Cortell S, Cohen JJ, Harrington JT. Allergic interstitial nephritis causing reversible renal failure in four patients with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1973;288:124-8.

48. Chan HL. Fixed drug eruptions. A study of 20 occurrences in Singapore. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:607-9.

49. Dillon PT, Babe J, Meloni CR, Canary JJ. Reserpine in thyrotoxic crisis. N Engl J Med. 1970;283:1020-3.

50. Rosenberg L, Shapiro S, Slone D, Kaufman DW, Miettinen OS, Stolley PD. Thiazides and acute cholecystitis. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:546-8.

51. Goldman JA, Neri A, Ovadia J, Eckerling B, Vries A, de. Effect of chlorothiazide on intravenous glucose tolerance in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1969;105:556-60.

52. Bird CC, Reeves BD. Effect of diuretic administration on urinary estriol levels in late pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1969;105:552-5.

53. Entrican JH, Denburg JA, Gauldie J, Kelton JG. Angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy associated with reserpine. Lancet. 1984;2:820-1.

54. Mack TM, Henderson BE, Gerkins VR, et al. Reserpine and breast cancer in a retirement community. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:1366-71.

55. Kodlin D, McCarthy N. Reserpine and breast cancer. Cancer. 1978;41:761-8.

56. Curb JD, Hardy RJ, Labarthe DR, Borhani NO, Taylor JO. Reserpine and breast cancer in the Hypertension Detection and Follow- Up Program. Hypertension. 1982;4:307-11.

57. Labarthe DR, O'Fallon WM. Reserpine and breast cancer. A community-based longitudinal study of 2,000 hypertensive women. JAMA. 1980;243:2304-10.

58. Jick H. Editorial: Reserpine and breast cancer: a perspective. JAMA. 1975;233:896-7.

59. Newball HH, Byar DP. Does reserpine increase prolactin and exacerbate cancer of prostate? Case control study. Urology. 1973;2:525-9.

Further information

Always consult your healthcare provider to ensure the information displayed on this page applies to your personal circumstances.

Some side effects may not be reported. You may report them to the FDA.