Imuran Side Effects

Generic name: azathioprine

Medically reviewed by Drugs.com. Last updated on Feb 6, 2024.

Note: This document contains side effect information about azathioprine. Some dosage forms listed on this page may not apply to the brand name Imuran.

Applies to azathioprine: oral tablet. Other dosage forms:

Warning

Oral route (Tablet)

MalignancyChronic immunosuppression with azathioprine, a purine antimetabolite increases risk of malignancy in humans. Reports of malignancy include post-transplant lymphoma and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Physicians using this drug should be very familiar with this risk as well as with the mutagenic potential to both men and women and with possible hematologic toxicities. Physicians should inform patients of the risk of malignancy with azathioprine.

Serious side effects of Imuran

Along with its needed effects, azathioprine (the active ingredient contained in Imuran) may cause some unwanted effects. Although not all of these side effects may occur, if they do occur they may need medical attention.

Check with your doctor immediately if any of the following side effects occur while taking azathioprine:

More common

- Black, tarry stools

- bleeding gums

- blood in the urine or stools

- chest pain

- chills

- cough

- fever

- hoarseness

- lower back or side pain

- painful or difficult urination

- pinpoint red spots on the skin

- sore throat

- sores, ulcers, or white spots on the lips or in the mouth

- swollen glands

- unusual bleeding or bruising

- unusual tiredness or weakness

Less common

- Cloudy urine

- fever sores on the skin

- general feeling of illness

- greatly decreased frequency of urination or amount of urine

- skin rash

- swelling of the feet or lower legs

- weight loss

- yellow skin or eyes

Rare

- Bloating

- clay-colored stools

- constipation

- dark urine

- decreased appetite

- diarrhea (severe)

- fast heartbeat

- fever (sudden)

- headache

- indigestion

- itching

- loss of appetite

- muscle or joint pain

- nausea (severe)

- pains in the stomach, side, or abdomen, possibly radiating to the back

- redness or blisters on the skin

- stomach pain or tenderness

- swelling of the feet or lower legs

- unusual feeling of discomfort or illness (sudden)

- vomiting (severe)

Incidence not known

- Difficulty with breathing

- difficulty with moving

- fat in the stool

- general feeling of illness

- pale skin

- sores on the skin

- stomach cramps

- sudden loss of weight

- troubled breathing with movement

- weight loss

Other side effects of Imuran

Some side effects of azathioprine may occur that usually do not need medical attention. These side effects may go away during treatment as your body adjusts to the medicine. Also, your health care professional may be able to tell you about ways to prevent or reduce some of these side effects.

Check with your health care professional if any of the following side effects continue or are bothersome or if you have any questions about them:

More common

- Nausea (mild)

- swollen joints

- vomiting (mild)

Less common

- Hair loss or thinning of the hair

For Healthcare Professionals

Applies to azathioprine: compounding powder, intravenous powder for injection, oral tablet.

General

The principal and potentially serious toxic effects of azathioprine (the active ingredient contained in Imuran) are hematologic and gastrointestinal. Risk of secondary infection and malignancy is also significant. Frequency and severity of side effects depend on dose and duration of azathioprine as well as on underlying disease or concomitant therapies. Hematologic toxicities and neoplasia were reported more often in renal homograft recipients than in patients using azathioprine for rheumatoid arthritis.[Ref]

Hematologic

Very common (10% or more): Depression of bone marrow function, leukopenia

Common (1% to 10%): Anemia, thrombocytopenia

Rare (Less than 0.1%): Agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, erythroid hypoplasia, megaloblastic anemia, pancytopenia

Frequency not reported: Bleeding, increased mean corpuscular volume and red cell hemoglobin content (reversible, dose-related)[Ref]

Bone marrow suppression is dose related and is the most common cause for dosage reductions. Leukopenia (any degree) has been reported in greater than 50% of renal homograft recipients and 28% of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Leukopenia (less than 2500/mm3 [2.5 x 10(9)/L]) has been reported in 16% of renal homograft recipients and 5.3% of rheumatoid arthritis patients.

There are data to support an increased risk of bone marrow aplasia in patients with very low or absent thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) activity. In patients with low TPMT activity, there is an increase in 6-thioguanine nucleotide (6-TGN) concentrations, a cytotoxic metabolite which suppresses purine synthesis. Death associated with pancytopenia has been reported in patients with absent TPMT activity receiving azathioprine. Bone marrow aplasia has been reported in patients with normal TPMT activity.

A 55-year-old male with pompholyx and deficiency of erythrocyte thiopurine methyltransferase experienced pancytopenia coincident with azathioprine therapy. Ten weeks after starting azathioprine 100 mg per day, a full blood count (during routine monitoring) showed moderate pancytopenia. Azathioprine was discontinued. Ten days later he was admitted to the hospital with malaise, lethargy, and deterioration in blood count. He was treated with blood and platelet transfusions and discharged eight days later with modest improvement in peripheral blood count.[Ref]

Gastrointestinal

Gastrointestinal side effects tend to be more problematic in the first few months of therapy. A 20-year-old man developed severe small-bowel villus atrophy and chronic diarrhea after starting azathioprine (the active ingredient contained in Imuran) 50 mg per day. Diarrhea completely resolved within 2 weeks after azathioprine discontinuation. Mucosal biopsies at 4 months post azathioprine discontinuation showed complete reversal of severe duodenal villus atrophy.

Complications such as colitis, diverticulitis, and bowel perforation have been primarily reported in transplant patients, and may be related to concomitant high-dose corticosteroid therapy. Pancreatitis occurs most commonly in organ recipients and patients with Crohn's disease.

There have been case reports of patients with symptoms that imitate viral gastroenteritis (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever) occurring hours after a single dose of azathioprine.[Ref]

Very common (10% or more): Nausea, vomiting

Uncommon (0.1% to 1%): Diarrhea, pancreatitis, steatorrhea

Rare (less than 0.1%): Colitis (transplant recipients), diverticulitis or intestinal perforation (transplant recipients), gastrointestinal ulcers (transplant recipients), intestinal hemorrhage (transplant recipients), necrosis (transplant recipients), severe diarrhea (inflammatory bowel disease patients)

Frequency not reported: Severe villus, sores in the mouth and on the lips[Ref]

Oncologic

The increased risk of cancer may be more pronounced when azathioprine (the active ingredient contained in Imuran) is used concomitantly with other immunosuppressive agents. Renal transplant patients may have a higher risk of developing lymphoproliferative disorders, lymphomas, and leukemia, as well as some solid tumors while receiving azathioprine.

Transplant patients as well as those with rheumatoid arthritis are often treated with multiple immunosuppressants; therefore, the true risk of neoplasia associated with azathioprine alone has yet to be determined.

A small increase in the risk of Epstein-Barr virus-positive lymphoma was seen in a study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with azathioprine.

The majority of reported cases of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma have bee in patients with Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis, and were adolescent and young adult males.[Ref]

Common (1% to 10%): Cervical cancer, Kaposi's sarcoma, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, vulval cancer (renal homograft patients)

Uncommon (0.1% to 1%): Lymphoproliferative diseases after transplantation

Rare (0.01% to 0.1%): Melanoma, non-Kaposi's sarcoma

Very rare (less than 0.01%): Acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes

Frequency not reported: Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma[Ref]

Hepatic

Common (1% to 10%): Hepatic dysfunction (including cholestasis, destructive cholangitis, peliosis hepatitis, perisinusoidal fibrosis, nodular regenerative hyperplasia) (organ transplant recipients)

Uncommon (0.1% to 1%): Hepatotoxicity, including elevation of serum alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, and/or serum transaminases

Rare (Less than 0.1%): Hepatic veno-occlusive disease, life-threatening hepatic damage

Frequency not reported: Acute focal hepatocellular necrosis, sinusoidal dilatation[Ref]

Hepatotoxicity usually occurs within the first six months of therapy and is more common in patients requiring immunosuppression following transplant than in patients requiring therapy for rheumatoid arthritis.

Hepatotoxicity is often manifest as cholestasis and/or acute focal hepatocellular necrosis, and is generally reversible following discontinuation of azathioprine therapy. However, permanent hepatic damage associated with cirrhosis, perisinusoidal fibrosis, hepatic peliosis, sinusoidal dilatation, and veno-occlusive disease is also reported. Several cases of nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver and at least one case of destructive cholangitis have been reported.

Veno-occlusive disease of the hepatic veins is due to an unknown mechanism, may affect males more often, usually precedes portal hypertension, and carries a poor prognosis. Numerous fatalities have been reported. Permanent discontinuation of azathioprine therapy is indicated if hepatic veno-occlusive disease is suspected.

A 51-year-old man developed jaundice and diffuse abdominal pain two months after the start of azathioprine 1.4 mg/kg/day. Biopsy reports confirmed destruction of the bile ducts consistent with destructive cholangitis. After discontinuation of azathioprine, the abdominal pain disappeared within 2 days and liver function tests improved and returned to normal values 8 weeks later.[Ref]

Hypersensitivity

Uncommon (0.1% to 1%): Hypersensitivity reactions, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis

Very rare (less than 0.01%): Hypersensitivity reactions with fatal outcome[Ref]

Idiosyncratic manifestations of hypersensitivity include general malaise, headache, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, rigors, exanthema, rash, vasculitis, myalgia, arthralgia, hypotension, renal dysfunction, hepatic dysfunction, cardiac dysrhythmia, and cholestasis. Rhabdomyolysis has been reported as part of an azathioprine hypersensitivity syndrome.

At least 3 cases of erythema nodosum, 2 cases of pustules, and 1 case of contact dermatitis have been reported. Erythema nodosum and pustules may be related to the clinical activity of inflammatory bowel disease. Relapse of such lesions shortly after rechallenge should raise the hypothesis of hypersensitivity rather than pharmacological manifestations.

Azathioprine should be permanently withdrawn after occurrence of hypersensitivity reactions.[Ref]

Cardiovascular

At least three cases of atrial fibrillation have been reported (one case involving a patient with ulcerative colitis), although causality is unknown. A 52-year-old male with steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis experienced atrial fibrillation coincident with azathioprine (the active ingredient contained in Imuran) therapy. The drug had been started 3 years earlier, but discontinued after a few months because the patient reported palpitations, lipothymia, nausea, and vomiting. Upon a rechallenge with 50 mg of azathioprine, the patient showed general malaise, nausea, and vomiting. An ECG showed atrial fibrillation, and the patient reported that the symptoms were similar to those experienced previously.

Azathioprine-induced hypotension is independent of dose and may accompany signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity. Hypotension may be profound, although it is usually responsive to intravenous fluids and, if hypersensitivity is suspected, corticosteroids.[Ref]

Rare (less than 0.01%): Hypotension, including cardiogenic shock

Frequency not reported: Atrial fibrillation[Ref]

Dermatologic

Common (1% to 10%): Alopecia

Frequency not reported: Exacerbation of dermatomyositis, rash, Sweet's syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis)[Ref]

Alopecia has been reported in patients on azathioprine monotherapy or in combination with other immunosuppressants. This side effect may resolve spontaneously despite ongoing therapy.

A female patient developed skin peeling syndrome eight months after the dosage of azathioprine was reduced to 25 mg daily. Skin lesions resolved 30 days after drug withdrawal.

Excess sun exposure, pale skin types, and duration of allograft seem to be important risk factors in the development of skin lesions.[Ref]

Genitourinary

Rare (less than 0.1%): Hematuria secondary to azathioprine-induced crystalluria[Ref]

Immunologic

Very common (10% or more): Viral, fungal, and bacterial infections (transplant recipients also receiving other immunosuppressants)

Common (1% to 10%): Susceptibility to infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease

Uncommon (0.1% to 1%): Viral, fungal, and bacterial infections (other indications)

Frequency not reported: Protozoal and opportunistic infections, including reactivation of latent infections, increased susceptibility to varicella and herpes zoster progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy[Ref]

Metabolic

Very common (10% or more): Anorexia

Frequency not reported: Negative nitrogen balance[Ref]

Musculoskeletal

Frequency not reported: Arthralgias, myalgias[Ref]

Nervous system

Frequency not reported: Alterations in sense of smell or taste, exacerbation of myasthenia gravis, meningitis[Ref]

Ocular

A patient with systemic lupus erythematosus and end-stage renal disease experienced CMV retinitis coincident with azathioprine (the active ingredient contained in Imuran) therapy. It is theorized that immunosuppressive therapy may have a role in the development of CMV retinitis in this population. The patient responded to discontinuation of azathioprine, lowering of the corticosteroid dose, and systemic administration of ganciclovir.[Ref]

Frequency not reported: CMV retinitis[Ref]

Renal

Elevation in serum creatinine and BUN accompanied by oliguria are usually associated with hypotension, and normalize after treatment with intravenous hydration and steroids. Cases of hematuria secondary to azathioprine-induced crystalluria may be less common with high urine output.

A reduction in the incidence of chronic allograft nephropathy has been reported during the extended follow-up (greater than or equal to 10 years) of patients (n=128) participating in a randomized trial that examined the conversion from cyclosporine to azathioprine (the active ingredient contained in Imuran) as early as three months after renal transplantation.

A 47-year-old female with Wegener's granulomatosis experienced rapid progression of renal failure within 10 days of starting azathioprine for vasculitis. Her creatinine was 119 mcmol/L at the time of presentation. Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis and no active glomerulonephritis were observed on renal biopsy. Her renal function started improving by day 6 post-admission and at one month post-admission her serum creatinine was 116 mcmol/L. She continued to have reasonable renal function and 16 months later had creatinine of 104 mcmol/L with no clinical evidence of recurrent interstitial nephritis.[Ref]

Frequency not reported: Acute interstitial nephritis, chronic allograft nephropathy, elevation in serum creatinine and BUN accompanied by oliguria[Ref]

Respiratory

Review of seven rare cases of azathioprine-associated interstitial pneumonitis revealed that the progression from alveolitis to pulmonary fibrosis may be dose-related.[Ref]

Rare (less than 0.01%): Reversible interstitial pneumonitis[Ref]

Other

There have been reports of fungal, protozoal, viral, and uncommon bacterial infections, some of which have been fatal, in patients who are receiving azathioprine (the active ingredient contained in Imuran) [Ref]

Frequency not reported: Delayed wound healing, fatigue, fever, malaise, oral lesions[Ref]

More about Imuran (azathioprine)

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (65)

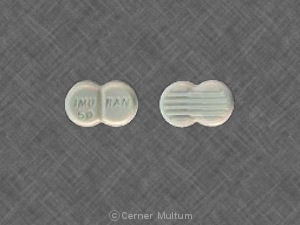

- Drug images

- Latest FDA alerts (4)

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Generic availability

- Drug class: antirheumatics

- Breastfeeding

- En español

Patient resources

- Imuran drug information

- Imuran (Azathioprine Intravenous) (Advanced Reading)

- Imuran (Azathioprine Oral) (Advanced Reading)

Other brands

Professional resources

Other brands

Related treatment guides

References

1. Loftus CG, Loftus EV, Tremaine WJ, Sandborn WJ. The safety profile of Azathioprine (AZA)/6-Mercaptopurine (6-MP) in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(9S):S242.

2. Elijovisch F, Krakoff LR. Captopril associated granulocytopenia in hypertension after renal transplantation. Lancet. 1980;1:927-8.

3. Lennard L, Van Loon JA, Weinshilboum RM. Pharmacogenetics of acute azathioprine toxicity: relationship to thiopurine methyltransferase genetic polymorphism. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1989;46:149-54.

4. DeClerck YA, Ettenger RB, Ortega JA, Pennisi AJ. Macrocytosis and pure RBC anemia caused by azathioprine. Am J Dis Child. 1980;134:377-9.

5. Hohlfeld R, Michels M, Heininger K, Besinger U, Toyka KV. Azathioprine toxicity during long-term immunosuppression of generalized myasthenia gravis. Neurology. 1988;38:258-61.

6. Nossent JC, Swaak AJ. Pancytopenia in systemic lupus erythematosus related to azathioprine. J Intern Med. 1990;227:69-72.

7. Hogge DE, Wilson DR, Shumak KH, Cattran DC. Reversible azathioprine-induced erythrocyte aplasia in a renal transplant recipient. Can Med Assoc J. 1982;126:512-3.

8. Singh G, Fries JF, Spitz P, Williams CA. Toxic effects of azathioprine in rheumatoid arthritis: a national post-marketing perspective. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:837-43.

9. Jeurissen ME, Boerbooms AM, Van de Putte LB. Pancytopenia related to azathioprine in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1988;47:503-5.

10. Speerstra F, Boerbooms AM, van de Putte LB, et al. Side-effects of azathioprine treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: analysis of 10 years of experience. Ann Rheum Dis. 1982;41:37-9.

11. Whisnant JK, Pelkey J. Rheumatoid arthritis: treatment with azathioprine (IMURAN (R)): clinical side-effects and laboratory abnormalities. Ann Rheum Dis. 1982;41:44-7.

12. Product Information. Imuran (azathioprine). Glaxo Wellcome. 2002;PROD.

13. Anstey A, Lennard L, Mayou SC, Kirby JD. Pancytopenia related to azathioprine-an enzyme deficiency caused by a common genetic polymorphism: a review. J R Soc Med. 1992;85:752-6.

14. Creemers GJ, van Boven WP, Lowenberg B, van der Heul C. Azathioprine-associated pure red cell aplasia. J Intern Med. 1993;233:85-7.

15. Agarwal SK, Mittal D, Tiwari SC, Dash SC, Saxena S, Saxena R, Mehta SN. Azathioprine-induced pure red blood cell aplasia in a renal transplant recipient. Nephron. 1993;63:471.

16. Kerstens PJ, Stolk JN, Hilbrands LB, Vandeputte LB, Deabreu RA, Boerbooms AM. 5-nucleotidase and azathioprine-related bone-marrow toxicity. Lancet. 1993;342:1245-6.

17. Kerstens PJSM, Stolk JN, Deabreu RA, Lambooy LHJ, Vandeputte LBA, Boerbooms AAMT. Azathioprine-related bone marrow toxicity and low activities of purine enzymes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:142-5.

18. Snow JL, Gibson LE. A pharmacogenetic basis for the safe and effective use of azathioprine and other thiopurine drugs in dermatologic patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:114-6.

19. Escousse A, Mousson C, Santona L, Zanetta G, Mounier J, Tanter Y, Duperray F, Rifle G, Chevet D. Azathioprine-induced pancytopenia in homozygous thiopurine methyltransferase-deficient renal transplant recipients: a family study. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:1739-42.

20. Bouhnik Y, Lemann M, Mary JY, Scemama G, Tai R, Matuchansky C, Modigliani R, Rambaud JC. Long-term follow-up of patients with crohn's disease treated with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine. Lancet. 1996;347:215-9.

21. Tassaneeyakul W, Srimarthpirom S, Reungjui S, Chansung K, Romphruk A. Azathioprine-induced fatal myelosuppression in a renal-transplant recipient who carried heterozygous TPMT*1/*3C. Transplantation. 2003;76:265-6.

22. Konstantopoulou M, Belgi A, Griffiths KD, Seale JR, Macfarlane AW. Azathioprine-induced pancytopenia in a patient with pompholyx and deficiency of erythrocyte thiopurine methyltransferase. BMJ. 2005;330:350-1.

23. Cerner Multum, Inc. Australian Product Information.

24. Duran S, Apte M, Alarcon GS, et al. Features associated with, and the impact of, hemolytic anemia in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: LX, results from a multiethnic cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1332-1340.

25. Drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2009;7:37-46.

26. Kawanishi H, Rudolph E, Bull FE. Azathioprine-induced acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:357.

27. Cochrane D, Adamson AR, Halsey JP. Adverse reactions to azathioprine mimicking gastroenteritis. 1987;14:1075.

28. Frick TW, Fryd DS, Goodale RL, Simmons RL, Sutherland DE, Najarian JS. Lack of association between azathioprine and acute pancreatitis in renal transplantation patients. Lancet. 1991;337:251-2.

29. Zaltzman M, Kallenbach J, Shapiro T, et al. Life-threatening hypotension associated with azathioprine therapy. S Afr Med J. 1984;65:306.

30. Assini JF, Hamilton R, Strosberg JM. Adverse reactions to azathioprine mimicking gastroenteritis. J Rheumatol. 1986;13:1117-8.

31. Cox J, Daneshmend TK, Hawkey CJ, Logan RF, Walt RP. Devastating diarrhoea caused by azathioprine: management difficulty in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1988;29:686-8.

32. Guillaume P, Grandjean E, Male PJ. Azathioprine-associated acute pancreatitis in the course of chronic active hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1984;29:78-80.

33. Pozniak AL, Ahern M, Blake DR. Azathioprine-induced shock. Br Med J. 1981;283:1548.

34. Amaro R, Neff GW, Karnam US, Tzakis AG, Raskin JB. Acquired hyperplastic gastric polyps in solid organ transplant patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2220-4.

35. Ziegler TR, Fernandez-Estivariz C, Gu LH, Fried MW, Leader LM. Severe villus atrophy and chronic malabsorption induced by azathioprine. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1950-7.

36. Floyd A, Pedersen L, Lauge Nielsen G, Thorlacius-Ussing O, Toft Sorensen H. Risk of acute pancreatitis in users of azathioprine: a population-based case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1305-8.

37. Patel AA, Swerlick RA, McCall CO. Azathioprine in dermatology: the past, the present, and the future. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:369-89.

38. Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee (ADRAC) and the Adverse Drug Reactions Unit of the TGA. Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin. http://www.tga.gov.au/adr/aadrb/aadr0612.htm 2007.

39. Eland IA, van Puijenbroek EP, Sturkenboom MJ, Wilson JH, Stricker BH. Drug-associated acute pancreatitis: twenty-one years of spontaneous reporting in The Netherlands. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2417-22.

40. Barreto SG, Tiong L, Williams R. Drug-induced acute pancreatitis in a cohort of 328 patients. A single-centre experience from Australia. JOP. 2011;12:581-5.

41. Tage-Jensen U, Schlichting P, Thomsen HF, et al. Malignancies following long-term azathioprine treatment in chronic liver disease. Liver. 1987;7:81-3.

42. Silman AJ, Petrie J, Hazleman B, Evans SJ. Lymphoproliferative cancer and other malignancy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with azathioprine: a 20 year follow up study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1988;47:988-92.

43. Wilkinson AH, Smith JL, Hunsicker LG, et al. Increased frequency of posttransplant lymphomas in patients treated with cyclosporine, azathioprine, and prednisone. Transplantation. 1989;47:293-6.

44. Or R, Kleinman Y, Chajek-Shaul T. Azathioprine and urinary bladder tumor. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99:737.

45. Connell WR, Kamm MA, Dickson M, Balkwill AM, Ritchie JK, Lennardjones JE. Long-term neoplasia risk after azathioprine treatment in inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet. 1994;343:1249-52.

46. Krishnan K, Adams P, Silveira S, Sheldon S, Dabich L. Therapy-related acute myeloid leukaemia following immunosuppression with azathioprine for polymyositis. Clin Lab Haematol. 1994;16:285-9.

47. Larvol L, Soule JC, Letourneau A. Reversible lymphoma in the setting of azathioprine therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:883-4.

48. Bottomley WW, Ford G, Cunliffe WJ, Cotterill JA. Aggressive squamous cell carcinomas developing in patients receiving long-term azathioprine. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:460-2.

49. Dayharsh GA, Loftus EV Jr, Sandborn WJ, et al. Epstein-Barr Virus-Positive Lymphoma in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treated With Azathioprine or 6-Mercaptopurine. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:72-77.

50. Langer RM, Jaray J, Toth A, Hidvegi M, Vegso G, Perner F. De novo tumors after kidney transplantation: the budapest experience. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1396-8.

51. Burger DC, Florin TH. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma following infliximab therapy for Crohn's disease. Med J Aust. 2009;190:341-2.

52. Millard PR, Herbertson BM, Evans DB, Calne RY. Azathioprine hepatotoxicity in renal transplantation. Transplantation. 1973;16:527-30.

53. Duvoux C, Kracht M, Lang P, Vernant JP, Zafrani ES, Dhumeaux D. Hyperplasie nodulaire regenerative du foie associee a la prise d'azathioprine. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1991;15:968-73.

54. Sterneck M, Wiesner R, Ascher N, et al. Azathioprine hepatotoxicity after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1991;14:806-10.

55. Mion F, Napoleon B, Berger F, Chevallier M, Bonvoisin S, Descos L. Azathioprine induced liver disease: nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver and perivenous fibrosis in a patient treated for multiple sclerosis. Gut. 1991;32:715-7.

56. Farge D, Parfrey PS, Forbes RD, Dandavino R, Guttmann RD. Reduction of azathioprine in renal transplant patients with chronic hepatitis. Transplantation. 1986;41:55-9.

57. Gerlag PG, van Hooff JP. Hepatic sinusoidal dilatation with portal hypertension during azathioprine treatment: a cause of chronic liver disease after kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1987;19:3699-703.

58. Liano F, Moreno A, Matesanz R, et al. Veno-occlusive hepatic disease of the liver in renal transplantation: is azathioprine the cause? Nephron. 1989;51:509-16.

59. Cooper C, Minihane N, Cotton DW, Cawley MI. Azathioprine hypersensitivity manifesting as acute focal hepatocellular necrosis. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:171-3.

60. Katska DA, Saul SH, Jorkasky D, Sigal H, Reynolds JC, Soloway RD. Azathioprine and hepatic venocclusive disease in renal transplant patients. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:446-54.

61. DePinho RA, Goldberg CS, Lefkowitch JH. Azathioprine and the liver: evidence favoring idiosyncratic, mixed cholestatic-hepatocellular injury in humans. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:162-5.

62. Lemley DE, Delacy LM, Seeff LB, Ishak KG, Nashel DJ. Azathioprine induced hepatic veno-occlusive disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989;48:342-6.

63. Jeurissen ME, Boerbooms AM, van de Putte LB, Kruijsen MW. Azathioprine induced fever, chills, rash, and hepatotoxicity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1990;49:25-7.

64. Read AE, Wiesner RH, LaBrecque DR, et al. Hepatic veno-occlusive disease associated with renal transplantation and azathioprine therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:651-5.

65. Small P, Lichter M. Probably azathioprine hepatotoxicity: a case report. Ann Allergy. 1989;62:518-20.

66. Meys E, Devogelaer JP, Geubel A, Rahier J, de Deuxchaisnes CN. Fever, hepatitis and acute interstitial nephritis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Concurrent manifestations of azathioprine hypersensitivity. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:807-9.

67. DavidNeto E, daFonseca JA, dePaula FJ, Nahas WC, Sabbaga E, Ianhez LE. The impact of azathioprine on chronic viral hepatitis in renal transplantation: A long-term, single-center, prospective study on azathioprine withdrawal. Transplantation. 1999;68:976-80.

68. Sobesky R, Dusoleil A, Condat B, Bedossa P, Buffet C, Pelletier G. Azathioprine-induced destructive cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:616-7.

69. Carmichael DJ, Hamilton DV, Evans DB, Stovin PG, Calne RY. Interstitial pneumonitis secondary to azathioprine in a renal transplant patient. Thorax. 1983;38:951-2.

70. Major GA, Moore PG. Profound circulatory collapse due to azathioprine. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:1052-3.

71. Cunningham T, Barraclough D, Muirden K. Azathioprine-induced shock. Br Med J. 1981;283:823-4.

72. Keystone EC, Schabas R. Hypotension with oliguria: a side-effect of azathioprine. Arthritis Rheum. 1981;24:1453-4.

73. Trotta F, Menegale G, Fiocchi O. Azathioprine-induced hypotension with oliguria. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1388-9.

74. Bergman SM, Krane NK, Leonard G, Soto-Aguilar MC, WAllin JD. Azathioprine and hypersensitivity vasculitis. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:83-4.

75. Saway PA, Heck LW, Bonner JR, Kirklin JK. Azathioprine hypersensitivity: case report and review of the literature. Am J Med. 1988;84:960-4.

76. Pandhi RK, Gupta LK, Girdhar M. Azathioprine-induced drug fever. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:198.

77. Knowles SR, Gupta AK, Shear NH, Sauder D. Azathioprine hypersensitivity-like reactions - a case report and a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:353-6.

78. Compton MR, Crosby DL. Rhabdomyolysis associated with azathioprine hypersensitivity syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1254-5.

79. Cerner Multum, Inc. UK Summary of Product Characteristics.

80. de Fonclare AL, Khosrotehrani K, Aractingi S, Duriez P, Cosnes J, Beaugerie L. Erythema Nodosum-like Eruption as a Manifestation of Azathioprine Hypersensitivity in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:744-8.

81. El-Azhary RA, Brunner KL, Gibson LE. Sweet syndrome as a manifestation of azathioprine hypersensitivity. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:1026-30.

82. Cooper HL, Louafi F, Friedmann PS. A case of conjugal azathioprine-induced contact hypersensitivity. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1524-6.

83. Dodd HJ, Tatnall FM, Sarkany I. Fast atrial fibrillation induced by treatment of psoriasis with azathioprine. Br Med J. 1985;291:706.

84. Brown G, Boldt C, Webb JG, Halperin L. Azathioprine-induced multisystem organ failure and cardiogenic shock. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17:815-8.

85. Cassinotti A, Massari A, Ferrara E, et al. New onset of atrial fibrillation after introduction of azathioprine in ulcerative colitis: case report and review of the literature. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:875-8.

86. HermannsLe T, Pierard GE. Azathioprine-induced skin peeling syndrome. Dermatology. 1997;194:175-6.

87. Benari Z, Mehta A, Lennard L, Burroughs AK. Azathioprine-induced myelosuppression due to thiopurine methyltransferase deficiency in a patient with autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;23:351-4.

88. Shahnaz S, Choksi MT, Tan IJ. Bilateral cytomegalovirus retinitis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus and end-stage renal disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:1412-5.

89. Duttera MJ, Carolla RL, Gallelli JF, et al. Hematuria and crystalluria after high-dose 6-mercaptopurine administration. N Engl J Med. 1972;287:292-4.

90. McHenry PM, Allan JG, Rodger RS, Lever RS. Nephrotoxicity due to azathioprine. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:106.

91. Bakker RC, Hollander AA, Mallat MJ, Bruijn JA, Paul LC, De Fijter JW. Conversion from cyclosporine to azathioprine at three months reduces the incidence of chronic allograft nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1027-34.

92. Bir K, Herzenberg AM, Carette S. Azathioprine induced acute interstitial nephritis as the cause of rapidly progressive renal failure in a patient with Wegener's granulomatosis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:185-7.

93. Bedrossian CW, Sussman J, Conklin RH, Kahan B. Azathioprine-associated interstitial pneumonitis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1984;82:148-54.

94. Krowka MJ, Breuer RI, Kehoe TJ. Azathioprine-associated pulmonary dysfunction. Chest. 1983;83:696-8.

Further information

Always consult your healthcare provider to ensure the information displayed on this page applies to your personal circumstances.

Some side effects may not be reported. You may report them to the FDA.