Mercaptopurine (Monograph)

Brand names: Purinethol, Purixan

Drug class: Antineoplastic Agents

Introduction

Antineoplastic and immunosuppressive agent; purine antagonist.103

Uses for Mercaptopurine

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)

Treatment of adults and pediatric patients with ALL as maintenance therapy in combination with other drugs.103 105 138

Crohn Disease

Has been used for management of moderate to severe or chronically active Crohn disease† [off-label].100 101 102 106 107 108 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 118 121 125 126 139

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines state that thiopurines are generally used for maintenance of remission or in combination with other therapies (e.g., tumor necrosis factor [TNF] blocking agents) for induction and maintenance of remission in patients with moderate to severe Crohn disease.139 140

Ulcerative Colitis

Has been used in the management of ulcerative colitis† [off-label].102

AGA guideline suggests the use of thiopurine monotherapy for maintenance of remission in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis; thiopurines also may be used in combination with TNF blocking agents, vedolizumab, or ustekinumab for remission induction.141

Mercaptopurine Dosage and Administration

General

Pretreatment Screening

-

Consider genetic testing (i.e., TPMT and NUDT15) or use of previous testing results to guide dosing recommendations.136

-

Verify pregnancy status in females of reproductive potential.103

Patient Monitoring

-

Monitor CBC and adjust dose to maintain ANC at desired level and avoid excessive myelosuppression.103

-

Monitor serum transaminase, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin at weekly intervals when first beginning therapy and at monthly intervals thereafter.103 Monitor liver tests more frequently in patients receiving other hepatotoxic drugs or those with pre-existing liver disease.103

-

Monitor for lymphoproliferative disorders and other malignancies such as skin cancers (melanoma and non-melanoma), sarcomas (Kaposi's and non- Kaposi's), and uterine cervical cancer in situ.103

-

Monitor for the development of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection.100 103

Dispensing and Administration Precautions

-

Handling and Disposal: Mercaptopurine is a cytotoxic drug; consult specialized references for procedures for proper handling and disposal.103

-

Based on the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), mercaptopurine is a high-alert medication that has a heightened risk of causing significant patient harm when used in error.142

Administration

Oral Administration

Administer orally as tablets or oral suspension.103 137 Take consistently, either with or without food.103 137

Do not administer tablets to patients who are unable to swallow tablets; use the oral suspension in these patients. 137

Shake the oral suspension for at least 30 seconds to mix.137 Use oral dispensing syringes to measure and dispense the dose.137 Use the suspension within 8 weeks; properly discard any remaining suspension after that time.137

If a dose is missed, skip the dose and continue therapy with the next dose.103

Pharmacogenomic Testing

Pharmacogenomic testing for thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT) and nucleotide diphosphatase (NUDT15) may be useful for identifying patients at increased risk for life-threatening myelosuppression, or evaluating those with severe myelosuppression or repeated episodes of myelosuppression during treatment.103 136 Patients with specific variants of TPMT and NUDT15 are likely to have increased systemic exposure to mercaptopurine and are at increased risk of myelosuppression.103 136

Dosage

Pediatric Patients

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)

Maintenance Therapy

OralUsually, 1.5–2.5 mg/kg once daily as part of a combination chemotherapy regimen.103 137

Adults

ALL

Maintenance Therapy

OralUsually 1.5–2.5 mg/kg once daily as part of a combination chemotherapy regimen.103

Crohn Disease† [off-label]

Oral

Maximal dosage of 0.75–1.5 mg/kg daily.140

Dosage Modifications in Patients with TPMT and NUDT15 Deficiency

TPMT intermediate or TPMT possible intermediate metabolizer: Start with reduced doses of mercaptopurine (30-80% of normal dose) if starting dose is ≥75 mg/m2/day or ≥1.5 mg/kg/day (e.g., start at 22.5-60 mg/m2/day or 0.45-1.2 mg/kg/day) and adjust doses based on degree of myelosuppression and disease specific guidelines.136 Allow 2–4 weeks to reach steady state after each dosage adjustment.136 If myelosuppression occurs, emphasis should be on reducing mercaptopurine over other agents, dependent on concomitant therapy.136 If normal starting dose is <75 mg/m2/day or <1.5 mg/kg/day, dose reduction may not be recommended.136

TPMT poor metabolizer: For malignancy, start with drastically reduced doses of mercaptopurine (reduce daily dose by 10-fold and reduce frequency to three times weekly instead of daily (e.g., 10 mg/m2/day given just 3 days/week) and adjust doses based on degree of myelosuppression and disease specific guidelines.136 Allow 4–6 weeks to reach steady state after each dosage adjustment.136 If myelosuppression occurs, emphasis should be on reducing mercaptopurine over other agents.136 For non-malignant conditions, consider alternative non-thiopurine immunosuppressant therapy.136

NUDT15 intermediate or NUDT15 possible intermediate metabolizer: Start with reduced mercaptopurine doses (30−80% of normal dose) if normal starting dose is ≥75 mg/m2/day or ≥1.5 mg/kg/day (e.g., start at 22.5–60 mg/m2/day or 0.45–1.2 mg/kg/day) and adjust doses based on degree of myelosuppression and disease-specific guidelines.136 Allow 2–4 weeks to reach steady state after each dosage adjustment.136 If myelosuppression occurs, emphasis should be on reducing mercaptopurine over other agents, depending on other therapy.136 If normal starting dose is <75 mg/m2/day or <1.5 mg/kg/day, dose reduction may not be recommended.136

NUDT15 poor metabolizer: For malignancy, initiate mercaptopurine at 10 mg/m2/day and adjust dose based on myelosuppression and disease-specific guidelines.136 Allow 4–6 weeks to reach steady state after each dosage adjustment.136 If myelosuppression occurs, emphasis should be on reducing mercaptopurine over other agents.136 For non-malignant conditions, consider alternative nonthiopurine immunosuppressant therapy.136

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

Use lowest recommended starting dosage.103 Adjust dosage to maintain ANC at a desirable level and for management of adverse reactions.103

Renal Impairment

Use lowest recommended starting dosage in patients with renal impairment (Clcr <50 mL/minute).103 Adjust dosage to maintain ANC at a desirable level and for management of adverse reactions.103

Geriatric Use

Select dosage with caution, usually starting at the low end of the dosing range.103

Cautions for Mercaptopurine

Contraindications

-

None.103

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Myelosuppression

Most consistent, dose-related adverse reaction is myelosuppression, manifested by anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, or any combination of these effects.103

Individuals who are homozygous deficient (2 nonfunctional alleles; poor metabolizer) for an inherited defect in theTPMT gene are unusually sensitive to myelosuppressive effects of mercaptopurine and prone to rapid bone marrow suppression.103 Substantial dosage reductions generally are required in such patients to avoid life-threatening suppression.103 Tolerance may vary in individuals who are heterozygous deficient (one nonfunctional allele; intermediate metabolizer) for the defect in theTPMT gene.103 137 Although some of these patients may experience greater toxicity, most will tolerate usual doses.103

Monitor CBC and adjust dosage for excessive myelosuppression.103 Consider testing for TPMT or NUDT15 deficiency in patients with severe myelosuppression or repeated episodes of myelosuppression.103 Patients with heterozygous or homozygous TPMT or NUDT15 deficiency may require dose reduction.103

Concomitant use of allopurinol may exacerbate myelotoxicity.103 Reduction of mercaptopurine dosage is required.103

Hepatotoxicity

Mercaptopurine is hepatotoxic; may be associated in some cases with anorexia, diarrhea, jaundice, and ascites.103 Hepatic encephalopathy and deaths attributed to hepatic necrosis reported.103

Hepatic injury occurs with any dosage, but may occur with greater frequency when recommended dosage exceeded.103

Clinically detectable jaundice usually appears early in treatment (1 to 2 months); however, it has been reported at 1 week and as late as 8 years after starting mercaptopurine.103 In some patients, jaundice resolved following withdrawal, but reappeared with rechallenge.103

Monitor serum transaminase levels, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin levels at weekly intervals when beginning therapy and at monthly intervals thereafter.103 Monitor liver tests more frequently in patients receiving mercaptopurine with other hepatotoxic drugs or those with pre-existing liver disease.103 Withhold mercaptopurine at onset of hepatotoxicity.103

Immunosuppression

May impair immune response to infectious agents or vaccines.103 Due to immunosuppression associated with maintenance chemotherapy for ALL, response to all vaccines may be diminished and there is a risk of infection with live virus vaccines.103

Consult immunization guidelines for recommendations regarding immunocompromised patients.103

Treatment-related Malignancies

May increase risk of neoplasia.103 Monitor for occurrence of malignancies.135

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma, a rare, aggressive, usually fatal malignancy, reported in mercaptopurine-treated patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)† [off-label].103 135

Patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy, including mercaptopurine, are at an increased risk of developing lymphoproliferative disorders and other malignancies, notably skin cancers (melanoma and non-melanoma), sarcomas (Kaposi's and non- Kaposi's) and uterine cervical cancer in situ.103

Risk appears to be related to degree and duration of immunosuppression.103 Discontinuation of immunosuppression may provide partial regression of the lymphoproliferative disorder.103 Treatment regimens containing multiple immunosuppressants (including thiopurines) should be used with caution as this could lead to potentially fatal lymphoproliferative disorders.103 A combination of concomitantly administered multiple immunosuppressants increases risk of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated lymphoproliferative disorders.103

Macrophage Activation Syndrome

Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS; hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis) may develop in patients with autoimmune conditions, in particular those with IBD† [off-label] .103 Patients receiving mercaptopurine may have increased susceptibility for this condition.103

Discontinue mercaptopurine if MAS occurs or is suspected.103

Monitor for and promptly treat infections such as EBV and CMV, as these are known triggers for MAS.103

Fetal/Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality

May cause fetal harm.103 Women who receive mercaptopurine during the first trimester have increased incidence of miscarriage.103 Miscarriage and stillbirth reported in women who receive mercaptopurine after first trimester of pregnancy.103

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Can cause fetal harm.103 Increased incidence of miscarriage and stillbirth.103 Advise pregnant women of the potential risk to a fetus.103

Lactation

No data on presence of mercaptopurine or its metabolites in human milk, effects on the breastfed child, or effects on milk production.103

Advise women not to breastfeed during treatment with mercaptopurine and for 1 week after final dose103

Females and Males of Reproductive Potential

Can cause fetal harm when administered to pregnant women.103

Verify pregnancy status in females of reproductive potential prior to initiating mercaptopurine.103

Advise females of reproductive potential to use effective contraception during treatment and for 6 months after final dose.103 Advise males with female partners of reproductive potential to use effective contraception during treatment with mercaptopurine and for 3 months after final dose.103

Based on findings from animal studies, can impair female and male fertility.103 Long-term effects, including reversibility, not studied.103

Pediatric Use

Safety and effectiveness not established, but use is supported by evidence from published literature and clinical experience.103

Symptomatic hypoglycemia reported in pediatric patients with ALL.103 Reported cases were in children <6 yearsof age or those with a low BMI.103

Geriatric Use

Insufficient numbers of patients ≥65 years of age to determine whether they respond differently from younger patients.103 Other clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between elderly and younger patients.103

Common Adverse Effects

ALL

Common adverse effects (>20%): myelosuppression, including anemia, neutropenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia.103

Common adverse effects (5–20%): anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, malaise, rash.103

Drug Interactions

Myelosuppressive Drugs

Possible increased risk of myelosuppression; consider reducing mercaptopurine dosage if used concomitantly.103 Monitor CBC and adjust dose for excessive myelosuppression.103

Hepatotoxic Drugs

Possible increased risk of hepatotoxicity; use concomitantly with caution and monitor hepatic function closely.103

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Allopurinol |

Possible decreased mercaptopurine metabolism and increased risk of myelotoxicity103 |

Reduce mercaptopurine dosage to 25–33% of usual dosage 103 |

|

Aminosalicylates (mesalamine, olsalazine, sulfasalazine) |

Possible decreased mercaptopurine metabolism and increased risk of myelotoxicity103 |

Use concomitantly with caution.103 Use lowest possible doses for each drug and monitor more frequently for myelosuppression103 |

|

Drugs affecting myelopoiesis (e.g., trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) |

Possible increased myelosuppression103 |

Monitor CBC; adjust dose of mercaptopurine for excessive myelosuppression103 |

|

Warfarin |

Possible inhibition of anticoagulant effect103 |

Monitor INR and adjust dosage as appropriate.103 |

Mercaptopurine Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Food may decrease exposure of mercaptopurine.103

Distribution

Extent

Only negligible concentrations attained in CSF.103

Not known whether mercaptopurine is distributed into human milk.103

Plasma Protein Binding

Approximately 19%.103

Elimination

Metabolism

Rapidly and extensively metabolized in liver by oxidation via xanthine oxidase to 6-thiouric acid.103 Also undergoes thiol methylation via the enzyme TPMT to form inactive metabolite, methyl-6-MP.103

Elimination Route

Excreted principally in urine (about 46%) as unchanged drug and metabolites within first 24 hours.103

Half-life

<2 hours after single oral dose.103

Stability

Storage

Oral

Tablets

20–25°C (excursions permitted to 15-30ºC).103

Suspension

15–25°C.137

Actions

-

Nucleoside metabolic inhibitor.103

-

Converted intracellularly to ribonucleotides that result in a sequential blockade of the synthesis and utilization of purine nucleotides.103

-

Inhibits synthesis of RNA and DNA.103

-

Also an immunosuppressant that inhibits primary immune response.103 134 136

Advice to Patients

-

Advise patients and caregivers that mercaptopurine can cause myelosuppression, hepatotoxicity, and GI toxicity.103 Advise patients to contact their healthcare provider if they experience fever, sore throat, jaundice, nausea, vomiting, signs of local infection, bleeding from any site, or symptoms suggestive of anemia.103

-

Instruct patients to minimize sun exposure due to risk of photosensitivity.103

-

Advise females of reproductive potential to inform their healthcare provider of a known or suspected pregnancy.103 Advise females of reproductive potential to use effective contraception during treatment with mercaptopurine and for 6 months after the final dose.103 Advise males with female partners of reproductive potential to use effective contraception during treatment with mercaptopurine and for 3 months after the final dose.103

-

Advise males and females of reproductive potential that mercaptopurine can impair fertility.103

-

Advise women not to breastfeed during treatment with mercaptopurine and for 1 week after the final dose.103

-

Importance of informing clinicians of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription (e.g., allopurinol) or OTC drugs, as well as concomitant illnesses.103

-

Inform patients of other important precautionary information103

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer’s labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

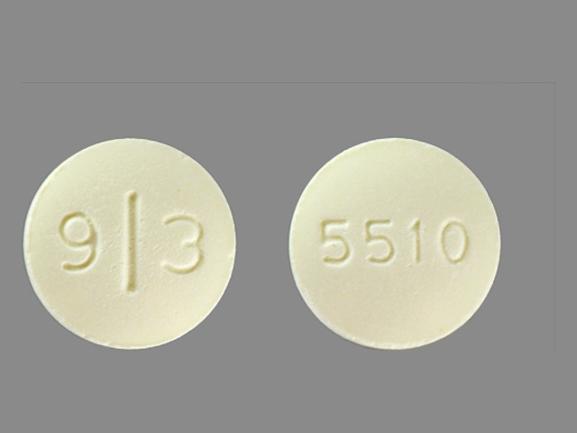

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Tablets |

50 mg* |

Mercaptopurine Tablets |

|

|

Purinethol (scored) |

Stason Pharmaceuticals |

|||

|

Suspension |

20 mg/mL |

Purixan |

Nova Laboratories |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2024, Selected Revisions November 17, 2023. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

Only references cited for selected revisions after 1984 are available electronically.

100. Present DH, Korelitz BI, Wisch N et al. Treatment of Crohn’s disease with 6-mercaptopurine: a long-term, randomized, double-blind study. N Engl J Med. 1980; 302:981-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6102739?dopt=AbstractPlus

101. Sleisenger MH. How should we treat Crohn’s disease? N Engl J Med. 1980; 302:1024-6. Editorial.

102. Sack DM, Peppercorn MA. Drug therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacotherapy. 1983; 3:158-76. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6136027?dopt=AbstractPlus

103. Stason Pharmaceuticals. Purinethol (mercaptopurine) tablets prescribing information. Irvine, CA; 2021 May.

104. Anon. Drugs of choice for cancer. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2003; 1:41-52.

105. Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. From: CancerNet/PDQ. Physician data query (database). Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2008 May 30.

106. Korelitz BI, Adler DJ, Mendelsohn RA et al. Long-term experience with 6-mercaptopurine in the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993; 88:1198-205. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8338087?dopt=AbstractPlus

107. Korelitz BI, Present DH. A history of immunosuppressive drugs in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: origins at The Mount Sinai Hospital. Mt Sinai J Med. 2000; 67: 214-26.

108. Bouhnik Y, Lémann M, Mary JY et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with Crohn’s disease treated with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine. Lancet. 1996; 347:215-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8551879?dopt=AbstractPlus

109. Pearson DC, May GR, Gordon H et al. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1995; 123:132-42. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7778826?dopt=AbstractPlus

110. Sandborn WJ. Azathioprine: state of the art in inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998; 33(Suppl 225):92-9.

111. Hanauer SB, Sandborn W, and the Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Management of Crohn’s disease in adults: Practice Guidelines. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001; 96:635-43. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11280528?dopt=AbstractPlus

112. Feagan BG. Maintenance therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003; 98(12 Suppl): S6-S17.

113. Podolsky DK. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347:417-29. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12167685?dopt=AbstractPlus

114. Scribano M, Prantera C. Review article: medical treatment of moderate to severe Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003; 17(Suppl. 2):23-30. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12786609?dopt=AbstractPlus

115. Biancone L, Tosti V, Fina D et al. Review article: maintenance treatment of Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003; 17(Suppl. 2):31-37. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12786610?dopt=AbstractPlus

116. American Gastroenterological Association position statement on perianal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2003; 125:1503-1507.

118. Hanauer SB, Present DH. The state of the art in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2003; 3:81-92. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12776005?dopt=AbstractPlus

119. Summers RW, Switz DM, Sessions JT Jr et al. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study: results of drug treatment. Gastroenterology. 1979; 77:847-69. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38176?dopt=AbstractPlus

120. Hanauer SB. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 1996; 334:841-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8596552?dopt=AbstractPlus

121. Markowitz J, Grancher K, Mandel F et al for the Subcommittee on Immunosuppressive Use of the Pediatric IBD Collaborative Research Forum. Immunosuppressive therapy in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: results of a survey of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993; 88:44-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8420272?dopt=AbstractPlus

122. Kirschner BS. Differences in the management of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents compared to adults. Neth J Med. 1998; 53:S13-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9883009?dopt=AbstractPlus

123. Markowitz J, Rosa J, Grancher K et al. Long-term 6-mercaptopurine treatment in adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1990; 99:1347-51. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1976562?dopt=AbstractPlus

124. Kirschner BS. Safety of azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1998; 115:813-21. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9753482?dopt=AbstractPlus

125. Sandborn W, Sutherland L, Pearson D et al. Azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease. In: The Cochrane Library. Issue 3. Chichester, United Kingdom: update software 2004.

126. Rutgeerts P. Review article: treatment of perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004; 20(Suppl 4):106-10. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15352905?dopt=AbstractPlus

127. Food and Drug Administration. Labeling and prescription drug advertising; content and format for labeling for human prescription drugs. 21 CFR Parts 201 and 202. Final Rule. [Docket No. 75N-0066] Fed Regist. 1979; 44:37434-67.

128. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Subpart B—Labeling requirements for prescription drugs and/or insulin. (21 CFR Ch. 1 (4-1-87 Ed.)). 1987:18-24.

129. Schmiegelow K, Glomstein A, Kristinsson J et al. Impact of morning versus evening schedule for oral methotrexate and 6-mercaptopurine on relapse risk for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nordic Society for Pediatric Hematology and Oncology (NOPHO). J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1997; 19:102-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9149738?dopt=AbstractPlus

130. Andersen JB, Szumlanski C, Weinshilboum RM et al. Pharmacokinetics, dose adjustments, and 6-mercaptopurine/methotrexate drug interactions in two patients with thiopurine methyltransferase deficiency. Acta Paediatr. 1998; 87:108-11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9510461?dopt=AbstractPlus

131. Relling MV, Hancock ML, Rivera GK et al. Mercaptopurine therapy intolerance and heterozygosity at the thiopurine S-methyltransferase gene locus. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999; 91:2001-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10580024?dopt=AbstractPlus

132. Evans WE, Hon YY, Bomgaars L et al. Preponderance of thiopurine S-methyltransferase deficiency and heterozygosity among patients intolerant to mercaptopurine or azathioprine. J Clin Oncol. 2001; 19:2293-301. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11304783?dopt=AbstractPlus

133. Haber CJ, Meltzer SJ, Present DH et al. Nature and course of pancreatitis caused by 6-mercaptopurine in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1986; 91:982-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2427386?dopt=AbstractPlus

134. Lichtenstein GR, Abreu MT, Cohen R et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute medical position statement on corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2006; 130:935-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16530531?dopt=AbstractPlus

135. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: Safety review update on reports of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in adolescents and young adults receiving tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers, azathioprine and/or mercaptopurine. Rockville, MD; 2011 Apr 14. From FDA website. Accessed 2011 Jul 26. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm250913.htm

136. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline for thiopurine dosing based on TPMT and NUDT15genotypes: 2018 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019; 105: 1095–1105.

137. Nova Laboratories. Purixan (mercaptopurine) suspension prescribing information. Franklin TN; 2020 Apr.

138. Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia treatment. From: PDQ. Physician data query (database). Bethesda MD: National Cancer Institute; 2023; August.

139. Feuerstein JD, Ho, EY, Shmidt E et al. AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Medical Managementof Moderate to Severe Luminal and Perianal Fistulizing Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology. 2021; 160:2496-2508.

140. Lichenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn's Disease in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113:481–517.

141. Feuerstein JD, Isaacs KL, Schneider Y, et al. AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Moderate to Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020; 158:1450-61.

142. Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). ISMP list of high-alert medications in acute care settings. ISMP; 2018.

More about mercaptopurine

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (31)

- Drug images

- Latest FDA alerts (3)

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: antimetabolites

- Breastfeeding

- En español